History has presented us with countless mysteries, some of which plague us to this day. What was Jack the Ripper? What happened to the Ark of the Covenant? Was Atlantis real? But other mysteries have proven easier to crack, in particular ancient codes and ciphers that people devoted years to solving, allowing us to catch a glimpse into a long forgotten world.

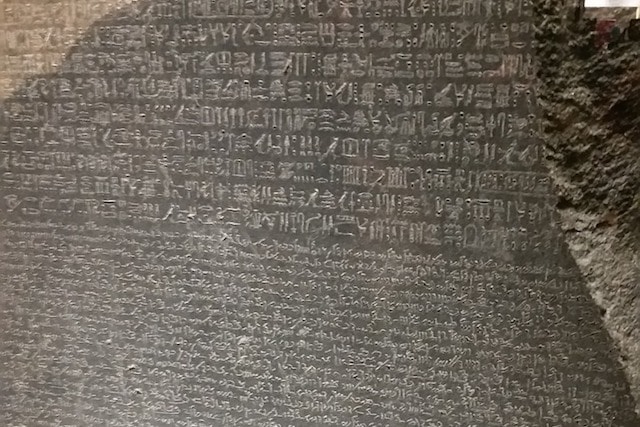

10. Hieroglyphics

Ancient Egypt has fascinated the modern world since long before it was even modern. The ancient culture is one of the most mysterious and awe-inspiring in all of human history. To this day, the pyramids stand as one of the great wonders of the world. But there was long a gap between their culture and our own and understanding them was far from an easy task, thanks in no small part to the language gap. Deciphering the hieroglyphs that covered pyramids, scrolls and sculptures would be the only way to understand a world that had existed as far back as the 28th century BC.

In the year 1799, a Frenchman named Bouchard working for Napoleon found the Rosetta Stone while digging the foundation for a fort near the town of Rashid. No one had been using hieroglyphs since around the 4th century, but the Rosetta Stone provided the key to understanding them. The stone featured the same decree written in Ancient Greek, Demotic script and hieroglyphs. It was essentially a roadmap for reading hieroglyphs.

Jean-Francois Champollion was able to compare the glyphs to the Greek text and first determine the names of Cleopatra and Ptolemy. In 1822, the code had been cracked and one of the oldest languages in the world was understood once more.

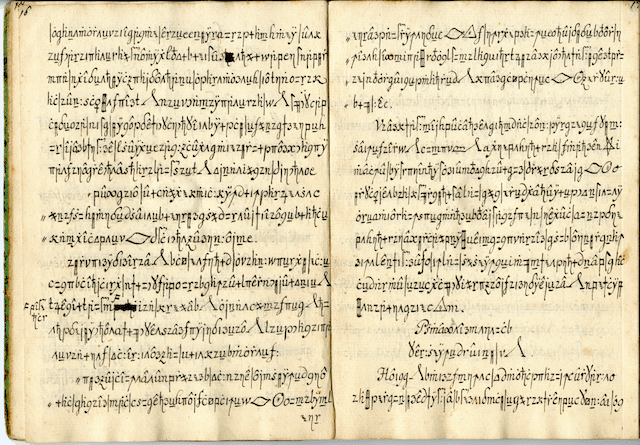

9. The Copiale Cipher

Few ciphers have as weird a history as the Copiale Cipher, a code used by a secret group known as the Oculist Order who all had a real thing for eye surgery despite none of them being surgeons. Nothing weird about that!

The cipher dates back to sometime between 1760 and 1780. There were 75,000 characters in a 105 page book, all handwritten in encrypted German. Roman letters and other symbols were used to make the cipher and cracking it required some modern computer technology in 2011.

Code breakers had a lengthy process figuring it out, including coming to the realization that the Roman letters were all there to be misleading and weren’t part of the words being translated.

8. The Vigenère Cipher

The Vigenère Cipher dates all the way back to 1553 when it was created by an Italian cryptologist named Giovan Battista Bellaso (though it earned its name from Blaise de Vigenère, to whom it was incorrectly attributed). Known today as a very simple code but, despite that, it remained unsolved for over 300 years. It was essentially a real testament to not seeing something, even when it’s right in your face.

Despite how easy people seem to think it is to break in the present, back in the day it was literally called “the unbreakable cipher.” The code uses what’s called polyalphabetic substitution in something called the Vigenère Square.

The Square involves writing the alphabet out 26 times. Each line is moved one space to the left compared to the one before it to create a table of substitutions. Throughout the cipher, you’d use different alphabets to create the code after choosing a keyword that can be used to decrypt it.

A German soldier and code breaker solved the cipher back in 1861 by following the pattern of repetition. If you’re interested, you can actually look up plenty of examples for how to encrypt or decrypt your own messages using it.

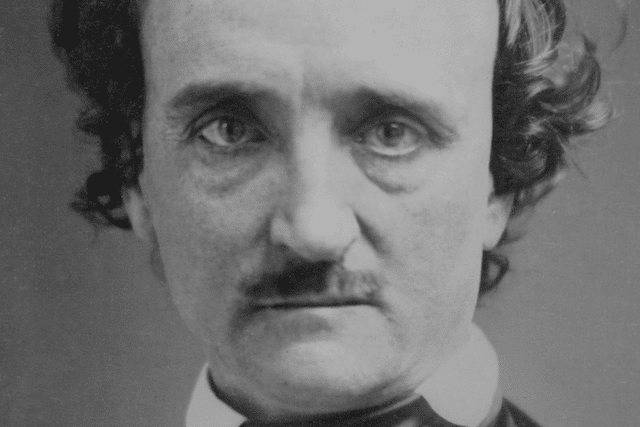

7. Poe’s Challenge

When Edgar Allan Poe issues a challenge, people listen. And in 1840 he wrote an article for a magazine asking for people to send him a cipher that he couldn’t crack. A challenge to see if they could best the famous author. It ran for six months and Poe claimed he’d solved every legit cipher people sent in. He also included two for readers to try their hand at solving from a person named Mr. W. B. Tyler.

Perhaps in a testament to Poe’s prowess as a code breaker or as a prank, because maybe he wrote them himself. The codes were not easy to crack at all. In fact, it took 150 years for someone to do it.

The first cipher was solved in 1992 and turned out to be text from a1713 play called Cato. But the second one was harder and Williams College put up a $2500 prize for anyone who could break it.

It wouldn’t be until the year 2000 when a software engineer from Toronto managed to figure it out. Part of the problem stemmed from errors in the typesetting as opposed to the cipher itself. Once it was solved, the message was revealed to just be a flowery bit of prose that was perhaps written by Poe but perhaps not as it offers no insight to who wrote it or why.

6. Beale Ciphers

Legend has it that Thomas J. Beale buried a fortune in gold and jewels back in the 1820s. He hid his treasure somewhere around Bedford, Virginia and then left a coded message relating to their location to an innkeeper.

There are three ciphertexts that need to be decoded to find the treasure. One tells you where the treasure is, one tells you what it is, and one tells you who owns it, plus their next of kin. Unfortunately, two of these ciphertexts have not been decoded yet. The third is unsolved, as well as the first. However, the second one was cracked, and it detailed what the treasure consisted of.

According to the deciphered text, Beale buried 1921 pounds of gold and 5000 pounds of silver, plus some jewels in iron pots under ground. The total value today is estimated to be somewhere around $100 million. That is, of course, if it’s real.

Legend has it that the innkeepers, years after receiving the ciphers and realizing Beale was never going to return, tried to crack it himself. He failed and sent it to a friend who used the Declaration of Independence as a key to solve the second cipher. Basically, one had to take the numbers from the cipher and then align them with the document. So the cipher may have said “67 98 1167” and that meant you need to look up the 67th, 98th and 1167th words of the Declaration.

To this day, no one has had any luck solving one and three. There are many who consider them to be a hoax as well, but the jury is still out on that. But hey, at least one was cracked and we know that somewhere out there, perhaps a small fortune awaits one brilliant code breaker.

5. Viking Love Letter

About 900 years ago, a pair of Vikings shared a message written in runic code. This came to be known as the jötunvillur code, and the nature of the message was lost for years. Was it raiding plans for attacking a village? A recipe for some mead? An epic poem about warriors fighting their way to Valhalla? Not exactly.

The runes used were carved into a piece of wood. The message was short and typical for the time period as many simple runic messages were used for literally dozens of reasons. The jötunvillur code is just one of several ciphers that might have been used at the time, but it’s also one of the most rare ones. Only nine examples of the code have ever been found, and it’s believed it was used more as a way of learning how to use runes rather than actually sending coded messages.

Vikings used these runic messages to write things like love letters and even jokes and graffiti. The jötunvillur code was the hardest to crack because there were so few examples, but luckily researchers found one in which two people signed their name using both the runes and a much more common script. The result allowed for the translation of the coded message, which turned out to just be “kiss me.”

Who said Vikings didn’t know how to have a good time?

4. The Philosopher’s Stone

No, it’s not just a Harry Potter title.

If you believe in alchemy, the Philosopher’s Stone is a substance that can turn simple metals like lead or iron into gold. And, arguably more important, it was the elixir of life. That meant it was supposedly capable of making you immortal.

In the 1600s, alchemist John Dee and his son Arthur put together a manuscript that included a cipher. It remained undeciphered until 2019, when a conference on alchemy and chemistry brought it to light. Two scholars with an interest in cracking the code wrote a blog that included the ciphertext in 2021 and put it out in the world for assistance from amateur code breakers. A man named Richard Bean cracked the code and determined that the code was actually a recipe for the Philosopher’s Stone. Whether anyone can follow the recipe and make the stone itself is another matter.

3. Cave Pterodactyl

Black Dragon Canyon in Utah has more than an amazing name. Caverns there feature ancient cave paintings that date back to somewhere between the year 1 and 1100, and were created by the Fremont culture. The pictures on the wall, created in a kind of red ink, have been debated for some time in an effort to determine what they might be. Are they people? Animals? Or, one of the most popular theories, a pterodactyl?

As strange a question as it seems, one of the paintings depicted a large bird-like creature with massive wings and a long neck that looked for all the world like a resident of Jurassic Park. And that led to the obvious question of how anyone in Utah a couple thousand years ago would have known what a pterodactyl looked like.

The painting was discovered in 1928 and for decades there was much speculation over the nature of the image. In 2015, with the help of some x-ray fluorescence and a novel piece of software that can help separate pigments, it was determined the image was actually 5 different images overlapping. In reality, it was a human-like figure and several animals, meaning the Fremont people had not, in fact, visited the Land of the Lost.

2. Linear B

Imagine the thrill archaeologist Arthur Evans must have felt back at the turn of the last century when, on the island of Crete, he discovered 3,000 stone tablets written in a language no living person had ever seen. That was the modern world’s first contact with Linear B.

The language dates back to around 1400 BC, far earlier than other known languages from the area and was the earlier form of what would become Greek. It predates what had previously been considered the Greek alphabet by hundreds of years.

Evans spent three decades working on deciphering what he’d found. His work was later taken up by Alice Kober, a scholar who also devoted her life to deciphering the script.

With the work Evans and Kober had done in place, an architect named Michael Ventris started trying to crack the code in his spare time, even doing so while he served in World War II. He began to translate ancient place names until the language was deciphered fully by Ventris and a man named John Chadwick in the late 1940s through to 1953, revealing itself not to be Minoan as some had suspected, but the earlier form of Greek.

1. Maya Glyphs

Back in the 16th Century, the thriving Maya culture was nearly destroyed completely by the Spanish. Those that survived had their culture stripped away. Their beliefs were replaced by Christianity and their language was replaced by Spanish. It’s a similar story to any time in history when an advanced conqueror comes and lays waste to a native population and the loss of culture and history is tragic.

Fortunately, some of the Maya world has survived, and that includes Maya glyphs. The all but lost language has been studied since the conquest of their culture began. Cortes is believed to have sent one of the four illustrated Maya books that still exists today back to Spain.

Deciphering the Maya glyphs proved to be a labored process. The Spanish had minimal success with them. Efforts picked up some steam in the 1800s, but it was not until the 1900s when many of them were finally translated fully. In 1981, the final piece of the puzzle was deciphered when the language was able to be read out loud for the first time in several hundred years.