Julius Caesar was known to say that he preferred a victory obtained by intelligence to one obtained by force, and George Washington once wrote, “The necessity of procuring good intelligence is apparent, and need not be further urged.”

Dozens of novelists and other writers have been spies or intelligence agents. They’re fascinating, mysterious people whose biographies are, in most cases, just as full of intrigue as the novels they churned out. Here are some of the most amazing novelists who also liked dabbling in espionage.

10. Compton Mackenzie (1883-1972)

The son of English traveling actors, Compton Mackenzie was urged to go on the stage. Instead, he wrote over 100 books, and was the founder of the influential music magazine, Gramophone. Starting as a file clerk in counter-intelligence he became the head of British counter-espionage in the Aegean during World War I and some of his books are about that experience. He later successfully battled a British government charge that he had used secret information in his writing. He was also a notable skirt-chaser though he had a beautiful and talented wife, Faith, also an author, who remained married to him for 55 years until her death in 1960.

Mackenzie, code-named ‘Z’ in the secret service, owned and lived on several islands and was one of the founders of the Scottish Nationalist movement. There is no doubt which way he would have voted in the recent election by which the Scots decided to stay with Mother England for the time being. Very much a product of the British Empire and English public (i.e. private) schools and Oxford, he was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II.

9. Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais (1732-1799)

Pierre Beaumarchais was everything James Bond is – and, astonishingly, more. Like Bond he was reliable, suffered violent attacks, succeeded with beautiful women, and carried on successful underground operations. He’s credited with bringing France into the Revolutionary War to help Americans against England and of killing the French aristocracy with laughter via his comedy The Marriage of Figaro. He spent time in prison and felt the breeze of the guillotine more than once but he survived. The author of The Barber of Seville and The Marriage of Figaro began life as apprentice to his father, a master watchmaker. Inventing a more accurate watch, young Beaumarchais was brought to the attention of the French king, Louis XV, and soon became the music teacher to the four royal princesses, all in their twenties.

He began his spying career working for the French Royals – going to London to buy off the publishers of scurrilous, anti-royal pamphlets. Thus learning the trade, he dedicated his talents to supporting America’s bid for independence. There is a fine statue of him today on the rue Saint-Antoine in Paris. Beaumarchais said, “If time were measured by the events that fill it, I have lived two hundred years.”

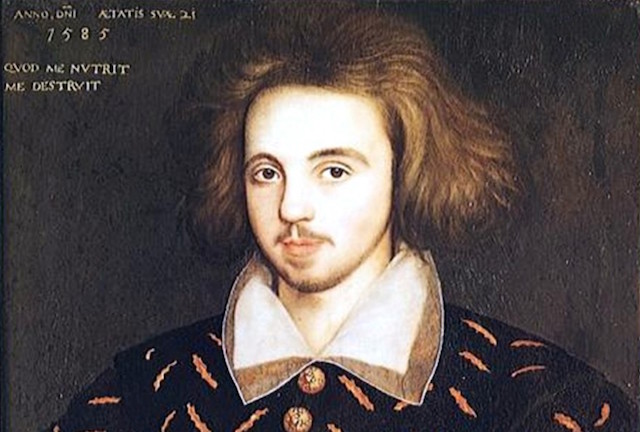

8. Christopher Marlowe (1564-1593)

Christopher Marlowe was the son of a shoemaker at Canterbury, England, born the same year as Shakespeare. He later created the more flexible blank verse that Shakespeare used to such advantage in his thirty-seven plays. While attending Cambridge University Marlowe was sent to France as a secret agent of the queen. He went on to become a famous playwright in London writing such plays as Tamburlaine, The Jew of Malta, and Dr. Faustus.

Marlowe liked to hang out with both aristocrats and gangsters, and with three of the latter, all connected to the secret service, he lunched in a tavern one day in 1593. After the meal he was stabbed to death, supposedly over an argument about the bill or “reckoning.” He was only twenty-nine years old. Shakespeare later referred to this in his play, As You Like It, as “a mighty reckoning in a little room.”

7. Somerset Maugham (1874-1965)

An Englishman, born in the British embassy in Paris, Somerset Maugham trained to be a doctor but his first novel was a hit and he went on to be a successful author for sixty-five years. An ambulance driver in World War I, he was recruited into the British secret service. He was sent to St. Petersburg in 1917 to try to keep the Bolsheviks from coming into power and removing Russia from the fight against the Germans.

From this experience he wrote a great short story, “Mr. Harrington’s Washing” and a prototypical spy novel, Ashenden, or the British Agent, about a gentlemanly, sophisticated, aloof spy. This work is considered the precursor of the works of his younger friend, Ian Fleming. Alfred Hitchcock’s Secret Agent (1938), starring John Gielgud, Peter Lorre, Madeleine Cornell and Robert young, was based on Ashenden. Maugham was also a very successful playwright, at one point having several of his plays running simultaneously on London stages.

6. Graham Greene (1904–1991)

Graham Greene, a relative of Robert Louis Stevenson on his mother’s side, with sixty-seven years of writing, was one of the great novelists of the 20th century. He was also a spy. He noted that novelists have something in common with spies: both watch, listen, seek motives, analyze character and are unscrupulous in serving their masters (i.e. literature for novelists). His spy novels include The Heart of the Matter and Our Man in Havana (which pokes fun at intelligence agencies.)

While a student at Oxford University, Greene began spying as a way out of boredom and also because he felt that Germany was being treated unfairly after World War I (People then did not know that World War II was on the way.) Out of this he gained a free trip through Germany for himself and a couple of pals. He tried to get a trip to Russia by offering to spy for them but the Russians didn’t bite.

All this life he sought roles and locales that would provide excitement. Thus as a boy he played Russian roulette with an older brother’s pistol and later found himself running a one-man secret service in Sierra Leone, living in a leper colony in the Congo, then at a Kikuyu reserve during the Mau-Mau insurrections and on to Malaya and to the French war in Vietnam.

5. Ian Fleming (1908-1964)

A product of the English upper classes, Ian Fleming, as assistant to the British Chief of Navy Intelligence during World War II, held a higher position than his creation, James Bond, who is merely an agent. Admiral John Godfrey, Fleming’s boss in the Naval Intelligence, became M in the novels. Fleming used the names of many other acquaintances, also. A lot of his success is due to his encyclopedic knowledge in many fields: guns, geography, languages (French, German, Russian), trees and flowers, wine, food, clothes (He could have been a fashion designer) and women, the minutiae of espionage.

He wrote a dozen Bond books (one-a-year on his annual two-month vacation at his place in Jamaica), as well as travel books, a children’s book, Chitty-Chitty Bang-Bang, and he was the owner of the leading rare books publication of his day. Fleming was a collector of first editions himself. His marriage to a high-charged society woman was in many ways unhappy (they liked to whip each other), but he had a long-term mistress in Jamaica with whom he got along well. His only child, Caspar, died aged 23 from a drug overdose.

4. F. W. Winterbotham (1897-1990)

F.W. Winterbotham was a British pilot in World War I, shot down by a famous squadron of German flyers. He put his 18 months in a prisoner-of-war camp to good use by learning German.

In the 1930s he traveled to Germany as one supposedly sympathetic to their cause and met with Hitler, Rosenberg and other Nazis who kindly showed him their plans and fortifications. Returning to England he became a leading light at Bletchley House as a member of the team that broke the German ENIGMA cryptographic machine and by so doing helped the allies win the war and do so quicker with less loss of life. Winterbotham’s job was to supervise the distribution of Ultra intelligence to Allied leaders and commanders in the field. There was never a leak.

Eisenhower said the work of Ultra had been decisive in winning the war and it was believed that without the relaying of thousands of top level (including those from Hitler) German messages to top Allied commanders in the field, the war might have gone on another two years and the Russians would have stopped not at Berlin but far to the west at the Rhine. The secrecy continued after the war and it was not till Winterbotham’s book of 1974, The Ultra Secret, that the truth became known.

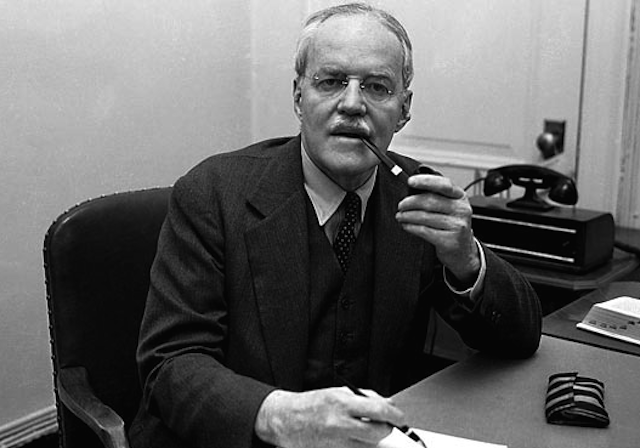

3. Allen Dulles (1893-1969)

Allen Dulles wrote his first book, The Boer War: A History, in 1902, when he was eight years old. It was pro-Boer though his grown-up relatives were pro-British. He had gained his facts from listening to their discussions as well as through independent research. His maternal grandfather, Secretary of State to President Benjamin Harrison at the time, was delighted and had the book published. It raised several hundred dollars for the relief of Boers and their families in English concentration camps.

Allen Dulles grew up to become a very successful chief of the Office of Special Services (OSS, predecessor of the CIA) at Berne, Switzerland, during World War II. A great German army in northern Italy surrendered through him, precluding a lot of loss of life. Later, Dulles became Director of the CIA under Presidents Eisenhower and Kennedy.

Near the end of his career Allen Dulles directed the disastrous Bay of Pigs invasion of Fidel Castro’s Cuba. President Kennedy, who had to take the heat for that, forced him to resign in 1962. After President Kennedy’s assassination, President Johnson appointed Dulles to the Warren Commission, which found no conspiracy in the murder of the late president.

2. Stella Rimington (born 1935)

Stella Rimington came from a family of miners. Her father had been wounded in World War I and she grew up with Nazi bombs falling around her in England. She was a good student but wanted to do something other with her life than, as she put it, just become a teacher. So she took a civil service job in archives and became an expert in collecting, analyzing and organizing records.

Her husband was sent as a diplomat to India. She accompanied him and there, in a garden, Rimington was tapped on the shoulder and asked, “Would you like to be a spy?” It was an invitation to become part of MI5, the department of the British Secret Service responsible for domestic counterintelligence (MI6 takes care of the stuff abroad). She accepted, thinking it might be fun, and 27 years later became the Director-General of MI5 , the first woman to do so, known as “K”. She was Director-General when the Soviet Union ceased to exist. Her work with MI5 went from dealing with the aggressive intelligence services of the Warsaw Pact during the Cold War to trying to stay a step ahead of the ever-proliferating terrorists, often the bomb-happy Provisional IRA funded by Omar Khadaffi. In 1991, with colleagues, she went on an official visit to former KGB agents in the Kremlin. Her account of the candid honesty of the Russians (they expected to go on spying as before) is most amusing.

For years she was a single mom of two daughters and she had to keep her occupation secret from family, friends, and neighbors. When her appointment as head of MI5 was announced to the media, she and the girls were driven out of their home by the ensuing publicity. She got to retire in 1996 when she was 61 and published her autobiography after it was approved by the Secret Service. However, she was surprised at the “ferocity of the reaction” it generated. Indeed, becoming a spy had turned out to be fun. She considered her position “the best job in the world.” She had helped to initiate many changes in the British Secret Service. “But,” she states, “there was a strong sense that though we had moved on a long way, we had not yet arrived anywhere.”

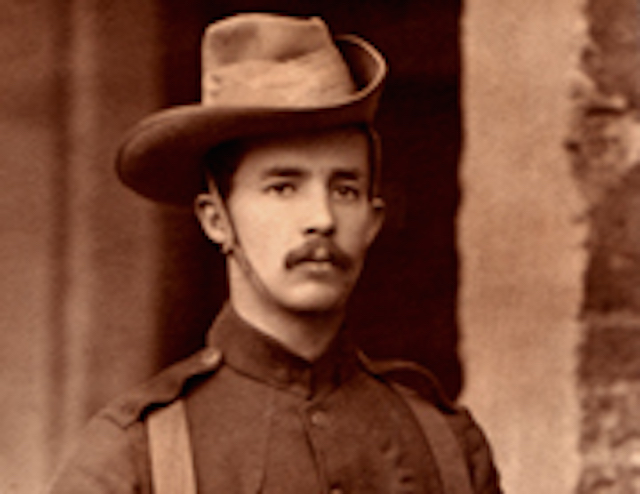

1. Erskine Childers (1870-1922)

Robert Erskine Childers was born in London but raised in Ireland. Beginning life as an extreme Tory, he finished it as a radical member of Sinn Fein. He loved to sail and explored all the coasts of southern England as well as those of the North Sea, including Germany. In 1903, he published a novel called The Riddle of the Sands, warning of England’s unpreparedness for the German build-up and threat. It was a bestseller and has never gone out of print.

He served on the first aircraft carriers (the seaplanes were carried on these converted ferries, but took off from and landed in the nearby waters, if they could). Erskine, who loved action, had served in the horse artillery in the Boer War and published many books about military strategy. The old-time staff however, did not want to accept his advice of replacing cavalry sabers with rifles. Throughout his life he learned a lot from people with less aristocratic backgrounds than his own. He became more and more liberal – finally becoming a die-hard Irish nationalist, running guns, with his American wife, Molly, from Germany into Ireland.

Later, captured by the forces of the new Irish government (pro-Treaty) in possession of a pistol given him by Michael Collins (recently assassinated), he was quickly tried and executed. Not allowed to see his wife before his execution, he wrote to her that he died happy, having enjoyed 19 years with her, and lived the good and useful life together. In 1973, their eldest son, Erskine, Jr., became the fourth President of the Republic of Ireland.