World War Two was fought on a colossal scale. Battles could last for months and involve millions of combatants. Major gains were rarely made without a vast expenditure of manpower and resources. However, there were rare occasions where a few men accomplished extraordinary things. With the advantage of surprise, preparation, and no small amount of luck, it was possible for a small force to inflict damage out of all proportion to its size.

10. The Battle of Fort Eben-Emael

Hitler’s plan for the invasion of Western Europe in 1940 comprised of two main components. While the bulk of Germany’s armored panzer divisions crept through the Ardennes Forest in an attempt to outflank France’s heavily fortified Maginot Line, a second large force would launch a more conventional attack across the border into Belgium.

The success of the plan relied on surprise and speed, but Belgium’s Fort Eben-Emael, the largest fort in the world, represented a formidable obstacle. Bristling with guns, protected by anti-tank ditches, and with walls some 40 meters high and 1.5 meters thick, it had the potential to stop an entire army in its tracks. The Germans intended to capture it with just eleven gliders and eighty men.

There was a great deal that could go wrong. Gliders had never been used in combat before, and the German pilots would have to improvise a landing in the very limited space available on top of the fort itself. Even if they brought their gliders down safely, the elite German paratroopers would be outnumbered 10-1 by the Belgian defenders.

While Hitler’s armies struck westwards in the early hours of May 10, 1940, the gliders approached the fort in semi-darkness. They took the Belgian defenders completely by surprise, and before the sun had even risen over the horizon German paratroopers were inside the fort itself destroying guns and wreaking havoc.

The Belgians didn’t know what had hit them. They were still struggling to regain control of Fort Eben-Emael twenty-four hours later when German ground forces began to arrive in force. The garrison surrendered later that day. Fort Eben-Emael had been specifically designed to defend Belgium’s borders from German aggression, but the Germans had taken it within a matter of hours at the cost of just six dead and fifteen wounded. Belgium surrendered to Germany just three weeks later

9. Saint Nazaire Raid

In the early hours of March 28, 1942 German sentries at the heavily-fortified town of Saint Nazaire spotted an unusual vessel approaching at speed. It flew the Nazi flag, bore a passing resemblance to a German destroyer, and it responded with the correct codes when signaled. On the other hand the Germans weren’t expecting the arrival of any ships, and their suspicions had been raised by reports of RAF bombers overhead.

The ship was the HMS Campbeltown, an aging British destroyer that had been disguised to resemble a German warship. The subterfuge didn’t stand close examination. As searchlights illuminated the HMS Campbeltown, the shore batteries let rip with a murderous volley of fire.

HMS Campbeltown increased its speed before colliding head-on with the huge gates of Saint Nazaire’s dry docks. More than 250 commandos poured off the warship and for the next several hours they swarmed over Saint Nazaire, destroying the dock’s pumping machinery and installations.

The Germans were impressed at the boldness of the raid, but the damage didn’t seem to be too severe. More than half of the commandos and Royal Navy personnel involved in the raid had been killed or captured, and it was expected that the vital dry docks would be operational again within a matter of weeks. This assessment of the situation changed dramatically at noon on March 28 when the huge bomb concealed in HMS Campbeltown’s hull exploded. The dry docks were comprehensively wrecked and put out of action for the remainder of the war.

8. Operation Frankton

The success of the Saint Nazaire raid led Hitler to order that any captured enemy commandos were to be executed. This considerably raised the stakes for the ten British Royal Marines who, on December 7, 1942, were dropped off by submarine at the Gironde estuary in southwest France.

As the submarine submerged and headed for home, the marines began the dangerous task of paddling their flimsy kayaks 100 miles through enemy territory towards the German-occupied port of Bordeaux. From here fast-moving German ships were breaking through the Allied blockade to return with vital supplies such as rubber from the Far East.

It took five days for the raiders to reach their target, by which time two kayaks and four marines were all that was left. The rest of the raiding party had been captured or lost to strong tides. The remaining marines waited for nightfall and then got to work attaching magnetic limpet mines to German ships, literally under the noses of the German sentries.

The resulting explosions caused so much damage that Churchill claimed the raid might have shortened the war by six months. All ten marines were presumed dead. However, two of them were running for their lives, pursued through France and then Spain until they finally reached the safety of Gibraltar in February 1943.

7. Alexandra Raid

Mussolini’s armed forces did not have a successful war. The Italian Air Force was made up of obsolete biplanes, the army relied on artillery of World War One vintage, and the Italian people had little desire to fight a war of conquest. Italy’s navy, while by far the most modern and effective branch of the Italian armed forces, suffered badly from a total lack of aircraft carriers.

Italy’s armies struggled to hold their own in almost every battle and campaign they took part in, but their special forces were not to be underestimated.

On December 19, 1941 a small group of Italian frogmen armed with manned torpedoes and magnetic limpet mines slipped unnoticed into the port of Alexandria, the Royal Navy’s most important port in the entire Eastern Mediterranean.

The raiders inflicted considerable damage. A destroyer and a tanker were destroyed. Two battleships were badly damaged, and one of them, the HMS Queen Elizabeth, was effectively sunk and would have been lost altogether had she not come to rest on the shallow harbor floor.

Just six Italian frogmen came closer to sinking a British battleship than the entire Italian surface fleet managed over the course of the entire war.

6. The Doolittle Raid

On December 7, 1941 more than 300 Japanese warplanes attacked the US Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor. In the months that followed, while the Japanese conquered vast swathes of territory across the Far East and the Pacific, the Americans were forced to fight a defensive war.

One American test pilot by the name of James Doolittle proposed a daring attack aimed at the Japanese Home Islands. The Americans didn’t have any airbases within striking range of Japan, but they did have aircraft carriers.

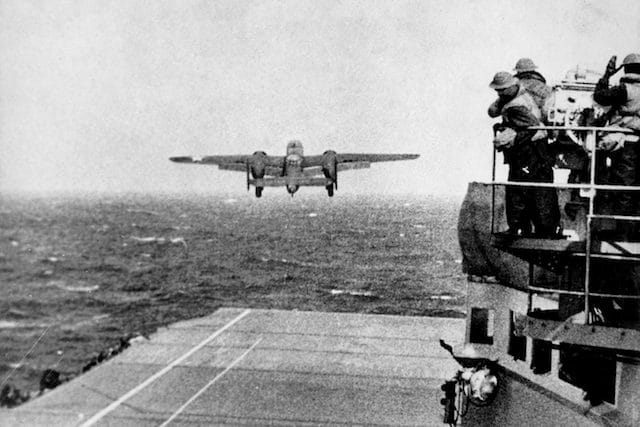

On April 18, 1942 the USS Hornet was sighted by a Japanese patrol craft. Fearing that their cover had been blown, Jimmy Doolittle led sixteen B25 Mitchell medium bombers off the flight deck and into the air. Bombers of this size were never intended to operate from carriers. Even stripped of most of their guns and armor, the lumbering machines groaned under the effort of getting airborne. There was no possibility of returning to the USS Hornet; the American aircraft carrier was already fleeing for safer waters. The raiders would have to attempt to fly on to air bases in China that lay at, or beyond, the limits of their range.

Doolittle’s raiders knocked out power to Tokyo for several hours, struck numerous factories, and damaged an aircraft carrier that had been undergoing upgrades at Yokosuka Naval Base. While the damage inflicted was slight in comparison with what would follow later in the war, it was far greater than could reasonably have been expected from a mere sixteen medium bombers. The Japanese now knew they were not invulnerable to attack from the air, and the Americans finally had some news to celebrate.

5. The Telemark Raid

The Allies suffered nightmares that the Germans might beat them in the race to develop a nuclear bomb. While the American nuclear program enjoyed better funding and government support, the Germans had one potentially game-changing advantage. Heavy water could potentially be used as a shortcut to producing weapons-grade uranium. There was only one facility in the world capable of producing heavy water, and unfortunately for the Allies it was located at Telemark deep in German-occupied Norway.

German air defenses, and the difficulties of bombing a target nestled amidst snow-capped Norwegian mountains, led the British to rule out an air strike. Instead, in October 1942, an advanced party of four Norwegian commandos with basic equipment and limited supplies parachuted into one of Europe’s most inhospitable regions.

Stage two of the operation went badly wrong when two gliders carrying a team of Royal Engineers crashed in appalling wintery conditions. Most of the engineers were killed outright, and the rest were tortured and executed by the Gestapo.

The Germans now knew that Telemark was a target, but British planners pledged to send support and continue with the operation regardless. Meanwhile, the Norwegian commandos struggled against one of the worst winters on record in a desperate battle to stay alive.

Reinforcements didn’t arrive until February 1943, by which time the Norwegian Commandos were suffering from malnourishment, having survived the winter on a meager diet consisting mostly of reindeer moss. All that remained was to clamber down a 200-meter cliff, cross an icy river, scale another almost vertical rock face, sneak into the heavy water factory, plant the explosives, evade capture by the Germans, and ski 250 miles to the safety of Sweden. Somehow they succeeded.

4. Operation Vengeance

Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto was one of the Imperial Japanese Navy’s senior commanders, the brains behind the attack on Pearl Harbor, and Japan’s most talented military strategist.

Yamamoto was intelligent, innovative, and bold. He spoke fluent English and having once lived in America, he understood the American psyche in a way that other Japanese military leaders did not. These qualities made him a dangerous opponent.

In April 1943, American codebreakers reported that Yamamoto would be flying into the Solomon Islands on an inspection tour. If the Americans attempted to intercept him, the Japanese might realize their codes had been cracked. President Roosevelt nonetheless decided that the opportunity to kill Yamamoto was worth the risk.

Yamamoto was noted for his punctuality, and on April 17, 1943 American P-38 Lightnings, operating at the very limits of their range, found him exactly where they expected him to be. While twelve of the American pilots engaged Yamamoto’s escorting Mitsubishi Zero fighters, the other four went after the two Japanese bombers, one of which was carrying the admiral himself.

Yamamoto was shot down and killed, and the Japanese never did realize their codes had been compromised. The loss of Yamamoto was a serious blow, and the authorities kept the news of his death hidden from the Japanese people for four weeks.

3. Dambusters

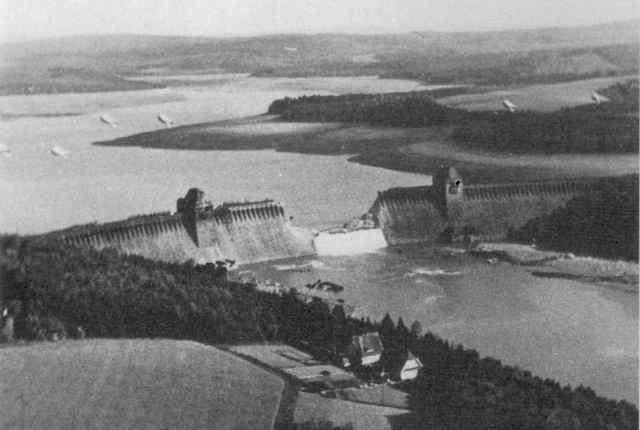

In early 1942 a British engineer by the name of Barnes Wallace came up with an idea so outrageous that almost nobody believed it could work. Wallace insisted he could develop a bomb that, when dropped from a precise height and speed, would bounce across the water like a skimming stone. If they struck just right, they could breach the huge dams that provided Germany with an important source of hydroelectric power.

Arthur Harris, chief of Britain’s Bomber Command, thought the plan insane and did everything in his considerable power to block it. Nonetheless, Wallace had friends in high places and just enough evidence to suggest he might be onto something.

On May 16-17, 1943, some nineteen Lancaster heavy bombers of the newly-formed 617 squadron struck into the heart of Nazi Germany without fighter escort, at night, before dropping their bombs with pinpoint accuracy from a height of just 60 feet. There was no margin for error. Enemy fighters, flak, trees, powerlines, and even the spray as their bombs struck the water were all potentially deadly foes. Even if the crews did everything right and the bombs found their mark, there could be no guarantee of success.

On a regular mission Bomber Command considered losses of 5% to be acceptable. This was a far more dangerous affair, and 53 of the 113 crewmen who set out never returned.

The raid was nonetheless a success. The bombs bounced, two dams were breached, and a third dam was damaged. The resulting flood wrecked factories and infrastructure, and the Germans were forced to divert a huge amount of resources toward repairs. Wallace’s belief that precision attacks were both possible and worthwhile was vindicated, and the men 617 Squadron achieved immortal fame for their courage and skill.

2. Rescuing Mussolini

On July 25, 1943 Benito Mussolini was overthrown and imprisoned by his own fascist government. The Italian people celebrated in the streets, but for Hitler it was yet another disaster. The war seemed to be turning decisively against the Axis powers, and Hitler rightly suspected that having got rid of Mussolini the Italians were plotting to make peace with the Allies.

Hitler ordered a resourceful and formidable SS officer named Otto Skorenzy to locate and rescue the deposed dictator.

Mussolini had been kept on the move by his captors, and Skorzeny’s first rescue attempt went wrong when the JU52 transport aircraft he was travelling in was shot down. Skorzeny soon tracked Mussolini down again, this time to a ski resort high in the Apennine Mountains.

The Luftwaffe had been developing a prototype helicopter, and the original plan was to use this in the raid. When it developed a fault Skorzeny and his men had to resort to the less high-tech method of crash landing gliders on the mountaintop close to where Mussolini was imprisoned.

Mussolini’s Italian guards hadn’t been expecting to be confronted by elite SS paratroopers, and they didn’t much fancy their chances in a firefight. Skorzeny persuaded them to lay down their arms, and Mussolini was sprung from captivity without a shot being fired.

While Mussolini was delighted to be rescued, it didn’t do him much good on the long run. In April 1945 he was captured by partisans and shot. With the collapse of Nazi Germany Skorenzy was himself imprisoned, but he escaped and fled to Spain where he set up an import/export business. Skorenzy used this business as a front as he worked to smuggle Nazi war criminals out of Europe to new lives in South America.

1. Sinking the Tirpitz

With the destruction of the docks at Saint Nazaire, Germany’s largest battleship, the Tirpitz, couldn’t be based on the French Atlantic Coast. The mighty warship instead spent the war lurking around Norwegian fjords, threatening the Allied Arctic convoys. Her isolation earned her the nickname “the Lonely Queen of the North.” Winston Churchill preferred to call her “the Beast.”

The Tirpitz’s continued existence was a source of immense frustration for Churchill, and between October 1940 and October 1944 the British launched more than twenty separate attacks against the battleship by sea and air.

With everything else having failed, the British once again turned to the precision bombing specialists of the Dambuster Squadron. The Tirpitz’s thick armor rendered it almost invulnerable to conventional bombs, so each aircraft would carry a single five-ton “tallboy” bomb, designed by Barnes Wallace and capable of punching through 5 meters of concrete.

The odds were not good. The Lancaster bombers would be operating at the limits of their range whilst stripped of armor and guns and carrying an extra 300 gallons of highly-explosive aviation fuel. To make matters worse two squadrons of fighter aircraft and some of Germany’s best pilots were stationed just 40 miles away from their target.

German radar spotted the approaching bombers with plenty of time to spare, but thanks to a catalogue of errors the fighters were not scrambled until an hour later. By the time the German fighters finally arrived on the scene the Tirpitz was upside down in the water and her assailants were on their way back to Britain. The Tirpitz had taken almost two-and-a-half-years to build, but she was sunk in the space of just ten-minutes by twenty-nine RAF Lancaster bombers.

1 Comment

It has been said that the Dambusters raid was the most significant single conventional bombing raid in history. As well as all the damage to railways, factories, roads, power stations, coalmines etc., a significant amount of damage to the Nazi cause was done the next day. An RAF photo-reconnaisance Spitfire flew over the dams and took photos of the damage. Within 48 hours, these pictures were front page news the world over. It is said that Hitler was so annoyed by this that he ordered workers to be taken off the building of the Atlantic Wall in order to repair the dams (which as everyone knows, they did in 6 months or so). He stipulated however that the workers in the Pas de Calais region be left constructing the wall as that was where the allies were going to invade. Instead, the workers were taken from …………Normandy!!! Hence Rommel’s displeasure at the lack of defences when he took command in that region in early 1944. D-Day could have been so different.