Once upon a time the creatures on this list were more or less common knowledge. Throughout the British Isles, they (or their variants) were feared or revered by adults and children alike. And while some on this list aren’t exclusive to England, they’re all squarely enshrined in its folklore. Here are 10 you might not have heard of…

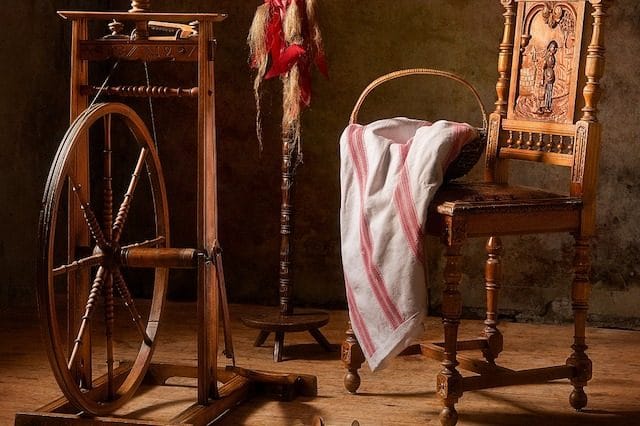

10. Habetrot

Dwelling underground in the North of England, Habetrot was a goddess of spinning. Such a prodigious spinner was she, in fact, that her lips were disfigured in the process—thickened and lengthened by her constantly licking her fingers while drawing the thread from the distaff (or spindle). In one old folk story, she came to the aid of a lazy young spinster who, not being able to spin for herself, was unlikely to find a good husband. With Habetrot spinning for her, on the other hand, not only could she marry a laird (or lord), she also retained her good looks.

Despite her witchy nature, living in a cave with her similarly hideous sisters, Habetrot was known for this kind of generosity. Anyone afflicted with grave-merels, for instance (a scabrous disease caught by treading on the graves of young children), could rely on old Habetrot, “Queen of the Spinsters,” for help. Because the only remedy, apparently, was to wear a sark (a skimpy women’s undergarment) spun by Habetrot herself from lint grown in 40-year-old manure.

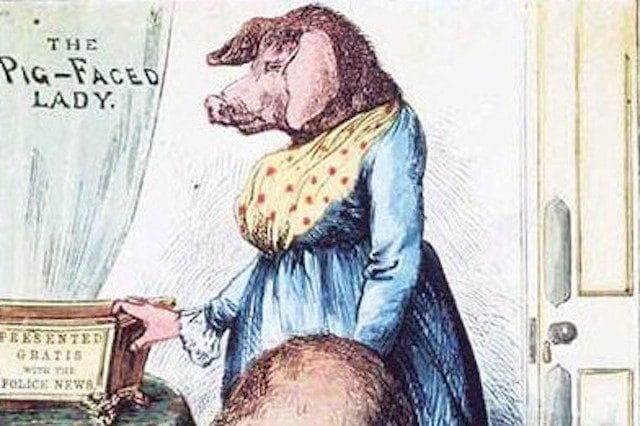

9. Pig-faced Women

In 1814 rumors began to emerge of a pig-faced lady living in Manchester Square, London. Despite her noble birth, she was said to be hideously ugly, cursed with the snout of a pig and forced to go about in a veil. Few saw her up close, people said, because she always used her own carriage; but there were plenty of artist’s impressions. One artist, John Fairburn, even made a pamphlet about the poor woman.

Following Napoleon’s defeat at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815, she was apparently seen for the last time ever. Seated in her carriage, her snout visible in an otherwise elegant bonnet, the pig-faced lady was watching the Piccadilly celebrations. But when an excited crowd began to converge on her carriage, her coachman promptly sped it away.

Tales like this were common throughout Europe, just as they had been in England from at least the 17th century on. They were so popular, in fact, that alleged specimens (really clean-shaven, drunken bears in dresses and wigs) were shamelessly exhibited at fairgrounds.

In one early tale, a young pig-faced Dutch woman named Tannakin Skinker, gave her new English husband a choice: either she could appear “young, faire, and lovely” to him but like a pig to all of his friends, or pretty to all of his friends and like a pig to him in his bed. Unable to make a decision, he left it up to her and thereby broke the curse entirely, having given his wife “that which all women most desire, [her] Will, and Sovereignty.”

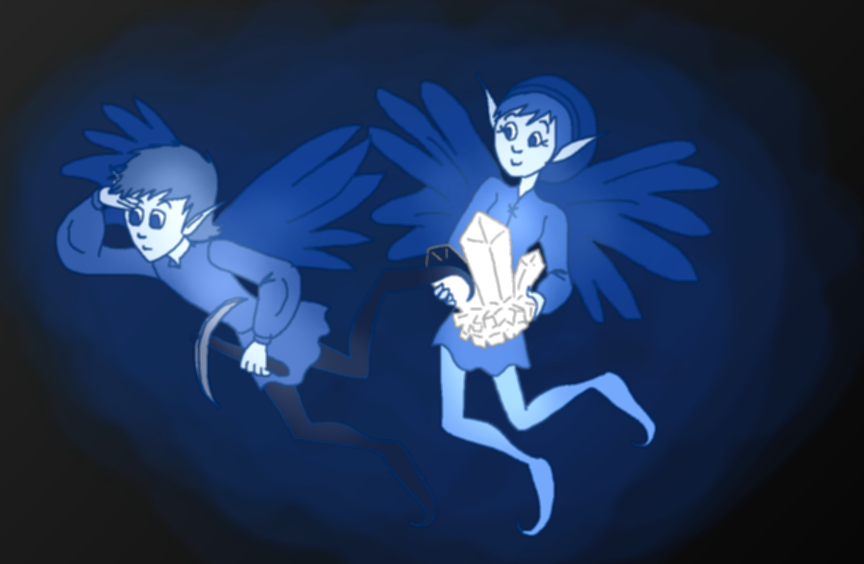

8. Blue Caps

Blue caps—a special kind of house elf or “brownie”—were tiddly little creatures and really more Scottish than English, but nevertheless common at the border. They were said to appear as glowing blue lights in the mines of the North, where they worked alongside human putters, or miners who filled baskets with coal.

They were thought to be so good at their jobs, in fact—apparently doing the work of a dozen men—that it was traditional to leave them a wage. And payments were generally well received, providing they were never more or less than the standard wage of the humans. If blue caps were paid more, they were said to go on strike in solidarity with their coworkers; and if they were paid less, they simply left the mines in droves.

It’s easy to imagine knackered, overworked miners seeing things down in the mines, which could explain the appearance of blue caps. But how these flickering phantom flames appeared to shift so much coal, as if “impelled by the sturdiest sinews,” is anyone’s guess.

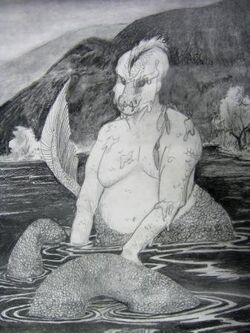

7. The Eachy

Everyone’s heard of the Loch Ness Monster but few have heard of the Eachy. Contrary to popular belief, it seems England has a lake monster too—possibly more than one, in fact— between Bassenthwaite and Windermere in the Lake District.

Unlike Nessie, however, the Eachy is said to be humanoid in appearance, something like Gill-man, The Creature from the Black Lagoon, but with a long and serpentine tail. Others say it’s pretty much all tail (13 feet of it) with three humps and the menacing head of a python.

Whatever it looks like, nobody’s seen one for real—although photographs allegedly surfaced in 1973. Earlier, in 1961, four atomic scientists actually went looking for the creature, snorkeling for an hour and a half in Bassenthwaite Lake. All they managed to find, however, were “an eel, half a dozen golf balls and a fishing rod.” Then again, it had been almost 90 years since the Eachy was first reported back in 1873.

6. Lubber Fiends

Not all weird and wonderful creatures dwell in the wild, whether underground or at the bottom of lakes. As “guardians of the household,” lubber fiends lived in the home.

Still, few ever managed to see them, emerging as they did from the nooks and crannies at night to carry out various chores: sweeping and cleaning, for instance, and especially caring for livestock. And it was customary—in fact mandatory—to leave a little dish of cream out as thanks, since those who didn’t found themselves subject to sabotage. As the poet Madison Cawein described it, a lubber fiend so mistreated “sweeps ashes in your face and …. bumps you shrieking on the floor; and at night he rides a mare round your bed and everywhere.”

Treating them too well, on the other hand, could mean they neglected their “duties.” Hence a sure way to get rid of a lubber fiend was to leave out a set of new clothes. After changing out of their rags and into relative finery, they were said to think of drudgery as beneath them and leave.

5. Church Grims

In the Middle Ages, animals were not only held responsible for certain crimes but actually tried for them in court. Hence, dead sows hanging from trees were a common sight throughout medieval Europe—often having been sentenced to death for “murdering” small children.

And animals were even held accountable for bestiality. In Sweden, assuming they weren’t let off on the grounds of otherwise “good character,” their punishment was to get buried alive with the rapist.

The legend of the English church grim (kyrkogrim in Swedish) appears to have similar roots. Animals or criminals were frequently buried alive under the cornerstones of new churches, apparently to consecrate the building to God. And from then on, they’d serve as guardian spirits of a sort, warding off witches and warlocks.

With their diminutive statures (less than two feet) and their dark, misshapen bodies, church grims in Yorkshire were somewhat mischievous as well, known for ringing church bells loudly at midnight.

4. Spriggans

Spriggans hail from the folklore of Cornwall, but nowadays they’re as widespread as elves—appearing in a variety of tabletop and video games, anime, and manga. Thought to be related to the trolls of Sweden and Denmark or, as some would have it, to “the Jews who crucified Jesus,” they’re described in The English Dialect Dictionary (1905) as a “mischievous and thievish tribe.”

Everything was blamed on the spriggans, from burglary and kidnappings to buildings falling down, but they were generally confined to the wild. As the guardians of buried treasure, they were said to haunt cairns (burial mounds), cromlechs (tombs), ruins, burrows, and barrows.

And much like the Cornish piskies (or pixies, of which spriggans are the evil counterparts), they’re generally thought to be small—although as “the ghosts of giants” they could sometimes make themselves huge.

They were also pretty ugly, with old, wizened faces and oversized children’s heads given to grinning and spitting maliciously. Worryingly for new parents, if a spriggan kidnapped a baby, it left its own ugly changeling in its place—a habit contrary to that of the piskies, who cared for and returned any human child that came their way.

3. Sooterkin

In his bizarre and condescending medical textbook The Female Physician (1724), the medic John Maubray related an unusual professional experience. Aboard a ferry between Harlingen and Amsterdam, he wrote, he saw a young woman give birth to a sooterkin—a mole-like creature with “a hooked snout, fiery sparkling eyes, a long round neck, and an acuminated short tail, of an extraordinary agility of feet.” According to Maubray’s account, the creature responded to the sudden appearance of light with fearful yells and shrieks, “running up and down like a little demon” in search of another hole to hide in.

Given that Maubray also thought it possible for a woman to give birth to rabbits (a known hoax of the time), his account is hardly reliable. But sooterkin were common enough in old wives’ tales, said to crawl inside pregnant women who spent too much time warming their nether regions on stove tops. Leeching nourishment away from the fetus, sooterkin left human infants dead and desiccated at birth while they emerged alive.

The name itself is thought to be an English corruption of the Dutch root suyger (or Middle Dutch zuigen), meaning “to suck,” the term “sooterkin” referring more to the soot of the implicated stove top.

2. Grindylows

Another species of lake monster, the grindylow, terrorized children in the northern counties of Yorkshire and Lancashire. Nowadays, they’re apparently much better known for their role in the Harry Potter franchise, and for hiding away in Newt Scamander’s suitcase in the movie Fantastic Beasts. But each of these versions has the same green skin, little horns, and sharp green teeth; the original grindylows differed only by their longer arms and fingers, which they used to grab inquisitive children from the lakeside and haul them into the depths.

The word “grindylow” may share a derivation with “Grendel,” the fen-dwelling brute from Beowulf, since gryndel was Middle English for “angry” and was also used in relation to lakes and bogs by the Anglo-Saxons.

Some grindylows, or grindylow-like beings, actually have names of their own, such as Peg and Nanny Powler of the River Tees and Skerne. Commonly described as “hags” or “river demons,” these creatures’ flowing green hair also marks them out as pagan deities—although their long, sharp teeth suggest a more menacing agenda. Like other grindylows, Peg Powler was said to prey on young children wandering too close to the water’s edge, particularly on the sabbath. And the foamy scum that gathered on the water’s surface, seemingly from all the grisly goings-on, was rather fiendishly described as “Peg Powler’s cream.”

1. Black Annis

In 1874 the Leicester Chronicle became obsessed with the story of Black Annis, a black-clad hermit reputed to “snatch [children] away to her ’bower’ where she scratched them to death with her claws, sucked their blood, and hung their skins out to dry.” First reported as fact in 1797 by one John Heyrick, a lieutenant of good standing locally, Black Annis had a “fierce and wild” eye, “vast talons, foul with human flesh,” and “livid blue” features. She was also said to wear the skins of her victims around her waist, drawing comparisons to the Hindu goddess Kali.

According to Heyrick, Black Annis’ Bower, a cave with an old oak tree over the entrance, lay in the Dane Hills region of Leicester, surrounded by sweet-smelling, violet flowers. And although nowadays this once densely forested area is built up with houses, Black Annis’ cave is still there—albeit in someone’s backyard.

Tales of the old witch abound: for instance, that daylight would turn her to stone; that she howled and ground her teeth so loudly that people knew she was coming; that she stole lambs as well as naughty children; and that she was slain with an axe at Christmas. It’s hard to believe she was in any way rooted in fact, but various theories exist. The classicist Robert Graves, for instance, thought she may have been Agnes Scott, an anchorite nun who lived in the area during the 1400s. Dressing in her long black habit, she’d probably have fit the bill—although it’s unlikely she preyed on children. Indeed, she was so revered by locals that she was buried at the church in Swithland and given a commemorative brass plaque. Other theories are that Black Annis represented the dark side of the Celtic mother-goddess Anu, or that she may have been a comet and not a being at all: “blue in appearance … with streams or talons of material coming off the fierce and wild cometary eye.”