When Apollo 13 lifted off from the John F. Kennedy Space Center on April 11, 1970 on America’s planned third visit to the surface of the moon, the general public greeted the event with a collective yawn. After just two manned visits to the moon the reaction by many to continuing lunar exploration was “been there, done that.” The major television networks broadcast the launch, as was customary, but declined to broadcast planned transmissions from the spacecraft as it journeyed to the moon, due to lack of viewership. After just four Americans had walked on the moon, the general public had lost interest. Serious discussions of canceling the remaining Apollo missions took place in political circles in Washington.

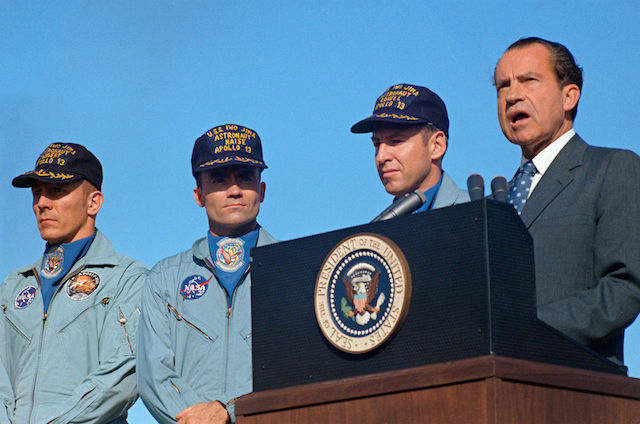

All that changed on April 14, when Jack Swigert (not James Lovell, as depicted in the film Apollo 13) informed mission controllers, “Houston, we’ve had a problem here.” An explosion and subsequent venting of precious oxygen ended the mission to the moon and threatened the lives of the three astronauts aboard, Jim Lovell, Jack Swigert, and Fred Haise. The mission to the moon became a gripping drama, as the crew and experts on the ground encountered and overcame problem after problem. The world watched the unfolding tale as it occurred, unsure of whether the three astronauts could be brought home alive.

Here are 10 facts about the Apollo 13 mission, which gained fame as NASA’s successful failure in the spring 1970.

10. Using the lunar module as a lifeboat was a planned and practiced evolution

The 1995 film, Apollo 13, brought the story of the ill-fated mission back into the popular imagination. The film, based on astronaut Jim Lovell’s book Lost Moon, presented the story with the usual dramatic license practiced by Hollywood (Lovell appeared in the film near the end, as a US Navy Admiral greeting his character as portrayed by Tom Hanks). One fictional aspect in the film was the implication that the Lunar Module (LM) was forced into service as a “lifeboat,” an evolution which was both unforeseen and unrehearsed. Neither was true. Use of the LM to provide shelter for the astronauts due to a casualty had been both envisioned by mission planners and simulated during training, as recalled years later by Ken Mattingly, who was dropped from the original crew at the last minute after being exposed to the measles.

“Somewhere in an earlier sim, there had been an occasion to do what they call LM lifeboat, which meant you had to get the crew out of the command module and into the lunar module, and they stayed there,” Mattingly recalled in an interview with NASA in 2001. Mattingly’s recollection, though admittedly vague, was that the training was intended to simulate unbreathable air in the Command Module (CM), with the astronauts using the LM while the CM was ventilated. During the Apollo 13 mission the LM supported the astronauts for a considerably longer period than had been simulated, but the use of the LM as a lifeboat in space had been foreseen and some procedures prepared before the astronauts experienced the problems which afflicted them on the journey to the moon.

9. Carbon dioxide buildup posed the greatest danger to the crew

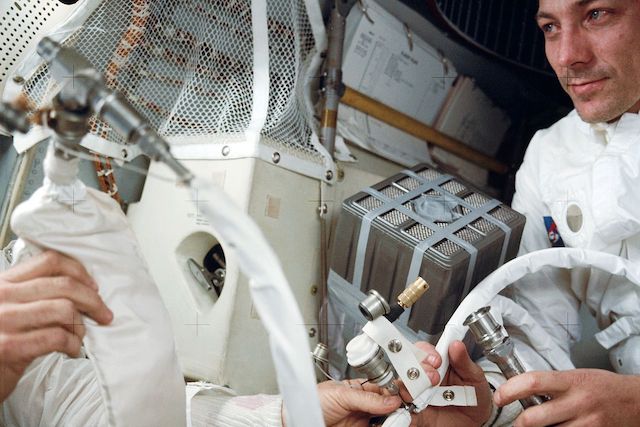

The loss of oxygen caused by the explosion of a tank during an attempt to stir its contents led to the assumption that the three astronauts were in danger of running out of air. Loss of oxygen did not present the greatest threat to survival. Nor did a shortage of water, though all three men observed strict rationing and all became dehydrated as a result. Fred Haise was so dehydrated he developed a kidney infection. According to Lovell in his book and subsequent interviews, the single greatest danger posed to the astronauts was from carbon dioxide buildup, which they created through breathing. The scrubbers in the LM, which used lithium hydroxide canisters to remove the carbon dioxide from the air, were insufficient for the exhalations of three men.

The ingenious modifications allowing the use of square canisters in scrubbers designed to use round ones did occur, developed by technicians and engineers in Houston. It, too, had a precedent, practiced on the ground in simulations. According to Mattingly, a similar device was contrived during the training for Apollo 8, coincidentally another mission flown by Lovell. “Well, on 13, someone says,” Mattingly recalled, “You remember what we did on the sim? Who did that?” The engineer who developed the procedure was located, and instructions to construct a similar device in Aquarius (Apollo 13’s LM — the CM was named Odyssey) were radioed to the astronauts.

8. The average age of the experts in mission control was just 29

The lead flight director for Apollo 13 — that is, the man in charge on the ground — was Gene Kranz. Kranz was just 36 years of age when the accident occurred during the mission. Still, in comparison to the team he commanded, known as the White Team in NASA parlance and dubbed the Tiger Team by the media, he was a grizzled veteran. A second team, the Black Team, performed the same functions when the White Team was off duty. The Black Team was led by Glynn Lunney. The average age of the engineers, scientists, and technicians which made up the teams was just 29. They were the men who established the limits of usage in the spacecraft of water, oxygen, and electrical power. They calculated the lengths of the engine burns to properly position and orient the spacecraft, and prepared modified procedures to restore the CM to operation in time for the astronauts to safely re-enter the atmosphere.

Many were recent graduates, on their first job out of school. They worked around the clock, supported by other astronauts in simulators and laboratories, as well as technical representatives (tech reps) from the primary contractors and subcontractors which built the components which comprised the Apollo spacecraft. In the movie Apollo 13, Ed Harris portrayed Gene Kranz as exhorting the teams, “failure is not an option.” Gene Kranz said he never made that statement during the unfolding of the mission. He didn’t have to. Kranz relied on dedication and talent of the young team around him. “Every person that was in this room lived to flaunt the odds,” he told an interviewer years later. “Watching and listening to your crew die is something that will impress upon your mind forever.”

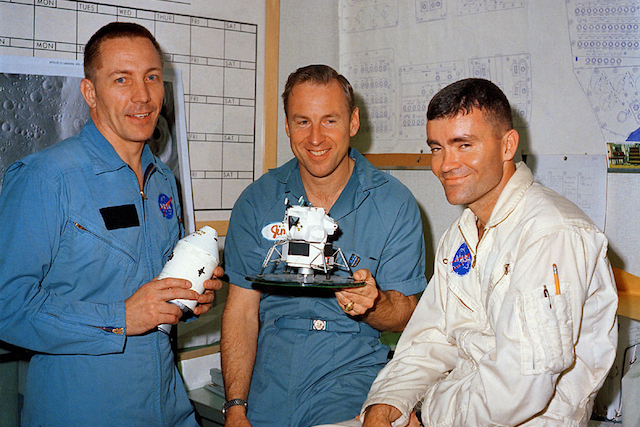

7. Lovell was on his fourth space flight, Swigert on his first (and only)

At the time Apollo 13 cleared the tower and began its journey to the moon, Mission Commander James Lovell was 42-years-old. A veteran of three previous flights, including two Gemini missions and the Apollo 8 voyage around the moon in December, 1968, Lovell had more hours in space than any other American. The three missions combined to give the former Naval Aviator 572 hours in space. Apollo 13 made Lovell the first person to fly to the moon twice. His companions, on the other hand — though both highly experienced pilots — were on their first journey into space.

For Jack Swigert, 38 and a veteran of the United States Air Force and Air National Guard, it was his first, and ultimately only, trip into space. Swigert was a last minute replacement for CM pilot Ken Mattingly, after his medical disqualification from being exposed to measles. Fred Haise, the designated LM pilot, was 35 and also on his first mission for NASA. Haise was a former US Marine Pilot, a civilian flight researcher for NASA and like his companion Swigert, never flew in space again. The average age of the crew for Apollo 13 was nearly a decade older than the members of the teams on the ground, on whom they relied for a safe return to Earth.

6. Ken Mattingly did help resolve the power conservation and startup problem

The film Apollo 13 depicted a resolved Mattingly (portrayed by Gary Sinise) working tirelessly in a Houston-based simulator to find a series of procedures through which the shut down CM could be restored to life. Mattingly was beset by the problem of needing power in excess of what was available in order to bring the stricken CM back to operation. According to the real Mattingly the scenes in the movie in which he attempts procedure after procedure, only to be frustrated by inadequate power reserves, is a false one. Mattingly did work, with other astronauts, to establish the steps to restore the CM. But the actual manner in which it was done had Mattingly outside of the simulator, reading procedures to astronauts within, in order to create the procedure for Lovell, Swigert, and Haise to use.

According to Mattingly, the astronauts included Thomas Stafford, Joseph Engle, and a third whom he hesitantly speculated may have been Stuart Roosa. Mattingly said the astronauts were put in the simulator and a series of procedures were read to them. “We’re going to call these out to you, and we want you to go through, just like Jack will. We’ll read it up to you. See if there are nomenclatures that we have made confusing or whatever.”

The reading of the procedures to Jack Swigert in the Odyssey was thus first rehearsed by Mattingly using astronauts in the simulator. In the real event, astronaut Joe Kerwin, serving as Capsule Communications (CAPCOM), read the start-up procedures step-by-step with Jack Swigert in the Odyssey.

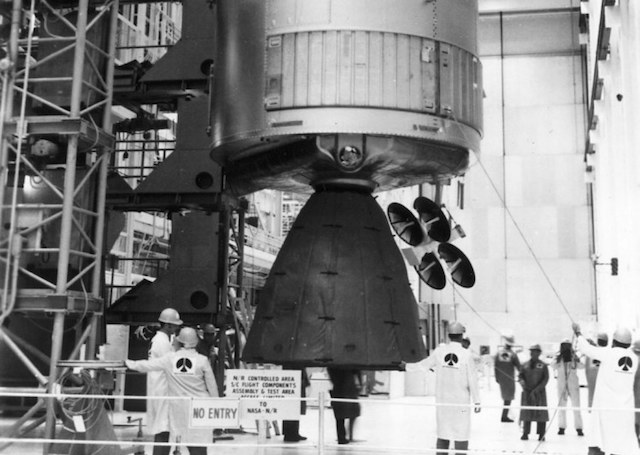

5. Firing the LM engine for course correction was also practiced before the Apollo missions

During development of the Apollo missions’ flight procedures, the Descent Propulsion System (DPS), was tested as a backup for the Service Propulsion System, the main engine on Apollo 13’s Service Module (SM). Firing, shutting down, and reigniting the DPS was performed in laboratories at both its leading contractor’s facilities and at NASA facilities. However, little research had been done using the LM to power the entire Apollo configuration of Lunar Module, Command Module, and Service Module. Flying the entire spacecraft from the LM was a novel experience, unique to Apollo 13. It was made necessary due to the unknown condition of the engine in the Service Module, and the necessity of shutting down the Command Module.

The DPS was fired to loop around the moon and begin the voyage back to Earth using a technique known as free return trajectory. As the spacecraft approached the Earth the need for a second burn of the DPS arose, to correct the trajectory and ensure the CM, carrying the three astronauts, would splash down in the Pacific near the recovery vessels on the scene. On an ordinary mission, the descent stage of the LM remained on the surface of the moon, the ascent stage crashed onto the lunar surface after delivering the astronauts to the CM for the voyage home. Aquarius, LM for Apollo 13, entered the Earth’s atmosphere entire, and burned up during the descent, after having fully lived up to its name, which means in astrology, the Water Bearer.

4. The astronauts used the Lunar Module engine for multiple burns

The first use of the DPS engine to control the direction of the Apollo spacecraft in space occurred as the astronauts looped around the moon. Prior to shutting down the CM and moving into the LM, the astronauts transferred critical navigational data to the latter’s guidance computers. As the astronauts gazed down at the lunar surface (the second time for Lovell), mission controllers confirmed a burn of the DPS engine for 34.23 seconds placed Odyssey and Aquarius on the necessary trajectory. The LM performed flawlessly as the astronauts emerged from the dark side of the moon. The Earth’s size began to increase through the spacecraft’s windows, the moon receded.

The trajectory to Earth indicated the CM would splash down in the Indian Ocean, where the United States Navy had relatively few of the assets needed for recovery. Nor was there sufficient time to move them there. A second burn was therefore required, to move the splash down near the recovery forces in the Pacific Ocean. The astronauts used the Sun as the fixed point of reference, centering the moon in Lovell’s window for the burn, which lasted 4 minutes and 23 seconds. After the completion of the second burn the LM was almost completely shut down, in order to conserve power for the rest of the voyage.

3. The astronauts used the moon as a fixed point of reference for one burn, Earth for the other

As Apollo 13 flew slowly back to the Earth, various factors caused it to drift slightly off course, necessitating another burn of the DPS engine on the LM. The burn used to establish the course on which they flew, known as trans-Earth injection, had been successful. Yet there was some doubt that the DPS engine would fire a third time, at least according to the film Apollo 13. In the real event, few doubted the DPS would perform as needed. The 14 second burn of the DPS guided the spacecraft to the correct trajectory, with Lovell and Haise using the line of demarcation between night and day on the Earth as their point of reference.

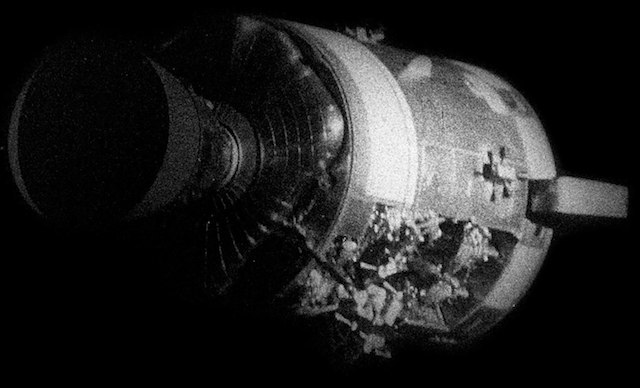

A final course adjustment, using the thrusters on the LM rather than the DPS engine, occurred just before the Service Module detached. It last 21.5 seconds, again using the day-night demarcation for reference. Once the course adjustment was completed the astronauts observed for the first time the damage sustained by the SM from the explosion. Lovell reported an entire panel missing, and Haise observed damage to the SM’s engine bell. Another problem arose over the release of the LM, a procedure which normally took place in lunar orbit. Grumman, the lead contractor for the LM, assigned a team of engineers at the University of Toronto to the problem; their solution was relayed to the astronauts, who applied it successfully. Aquarius was released just as re-entry began.

2. The temperature within the spacecraft dropped to 38 degrees, not freezing food

A major plot device in the film Apollo 13 was the cold conditions within the spacecraft, with condensation freezing on panels in the Command Module, windows frosting over, and food freezing hard. The spacecraft was cold and damp, but it did not freeze. The temperature dropped to about 38 degrees Fahrenheit. The astronauts were subject to the cold conditions, which Lovell and Haise fought by wearing the boots in which they had planned to trod on the lunar surface. Lovell considered ordering the crew to wear their spacesuits before rejecting the idea, believing they would be too cumbersome and hot. Swigert donned a second set of overalls, though he suffered from cold feet.

Swigert had collected and bagged as much water as he could as the astronauts shut down Odyssey and moved into Aquarius. During the process, in which he drew water from the tap in the CM, his feet became wet, and in the cold, damp, conditions never fully dried. Despite his efforts gathering water, the crew sustained themselves with a ration of just over 6 ounces per day for the remainder of the flight, leading to significant dehydration and weight loss for all of them. They also consumed as much of the juices found aboard as they could, and what little they ate came from foods labeled as “wet-pack,” indicating some water was contained.

1. Apollo 13 led to several design changes for subsequent missions

The lessons learned from Apollo 13 led to several changes to the configuration of all three components of the Apollo spacecraft, the Command Module, Service Module, and Lunar Module. Additional water storage was added to the CM, and an emergency battery for backup power was installed. Modifications to simplify the transfer of electrical power between the LM and CM were adopted for future missions. The oxygen tank which exploded — creating the crisis — was redesigned with additional safety features installed. Monitoring for anomalies improved both aboard the spacecraft and in the control panels and telemetry screens of mission control.

None of the three astronauts ever flew in space again, with Lovell retiring from NASA in 1973. Haise was scheduled to command Apollo 19, but the mission was canceled. Only four more missions to the moon were carried out before Apollo 17 ended the manned lunar explorations in December 1972. By then public interest in the space program had again waned, the burst of national pride initiated by the successful return of the Apollo 13 astronauts having proved short-lived. Now 50 years later, Apollo 13 remains one of the most dramatic stories of humanity’s short experience working in outer space, a story of disaster, ingenuity, courage, and perseverance.