Alexander Hamilton came from humble beginnings, but eventually became one of the Founding Fathers of the United States and the first Secretary of the Treasury. While he never became President, he was an incredibly influential figure in the formation of America and an indelible part of its history. Here are 10 things about Lin-Manuel Miranda’s muse you may not know…

10. He Lied About His Age

When Alexander Hamilton’s mother, Rachel Fawcett, was a teenager, she was living on the island of Nevis in the British West Indies, and she was forced to marry a much older man named John Lavine. Rachel, who was a descendant of British and French Huguenot parents, wasn’t happy in the marriage. Lavine was abusive and spent all the money Rachel had inherited from her father’s death. Eventually, Lavine had her locked up in prison for adultery.

After getting out of prison, Rachel didn’t go back to her husband and the son they had together. Instead she fled to St. Kitts, where she lived with a Scottish trader named James Hamilton. Rachel gave birth to a son in 1753, and then Alexander Hamilton was born on January 11, 1755… even though he told people he was born in 1757.

Why Hamilton lied about his age stems from the fact that his father abandoned him, his brother, and his mother shortly after he was born. This left the family in poverty while living in Saint Croix and when Hamilton was 13, his mother died. Now having to support himself, Hamilton needed to find an apprenticeship. He thought that if he was 11, he would make a more desirable apprentice. Luckily for him, it worked and he got a job as a clerk.

9. He Came to America Because He Was a Good Writer

In August 1772, when Hamilton was 17 (but telling people he was 15) the West Indies was hit by a horrible hurricane. Hamilton, who was working as a clerk, wrote about the hurricane in a letter that he planned on sending to his father. However, first he showed it to a Presbyterian minister named Hugh Knox, who was also mentoring him. In an interesting side note, Knox was ordained as a minister by Aaron Burr Sr., the father of Vice President Aaron Burr. As you probably know if you ever studied American history, Aaron Burr is going to be a big part of this list.

But, back to the letter – Knox read it and was impressed with Hamilton’s writing. He encouraged Hamilton to publish it in the newspaper where Knox filled in as an editor. It was printed in October along with a foreword by Knox. After the letter was published, several businessmen in St. Croix wanted to know the identity of the writer and when Hamilton came forward, they took up a collection to send him to America to be educated. Several months later, Hamilton was sent to New York where he enrolled in King’s College (which is now Columbia).

Now, many of you are probably aware that there is a musical about Hamilton aptly named Hamilton. The musicial is told entirely in rap and it features all minority actors. The creator of the play, Lin-Manuel Miranda, said that Hamilton’s letter inspired the play. In an interview with Vogue he stated, “It was the fact that Hamilton wrote his way off the island where he grew up. That’s the hip-hop narrative.”

Also, by immigrating to New York, it makes Hamilton the only key Founding Father who wasn’t born in one of the states.

8. He Passed the New York Bar Exam After Studying for Only Six Months

During the American Revolution, Hamilton joined the Patriots to fight against the Loyalists. Hamilton quickly caught the attention of General George Washington, who made him an assistant and an adviser. During this time, Hamilton wrote several important letters and reports for Washington.

During his tenure as adviser, Hamilton saw a big problem with the fledgling American nation; mainly that the states were resentful and jealous of each other. He thought that a strong central government would improve relations between the states and strengthen the country. To help create a stronger central government, Hamilton decided to become a lawyer. In 1782, he left his post as an adviser to Washington after holding it for five years, and studied to take the bar exam. People can take years to study for the bar, but amazingly, it only took Hamilton six months to prepare. He passed and became a lawyer in New York City in 1782.

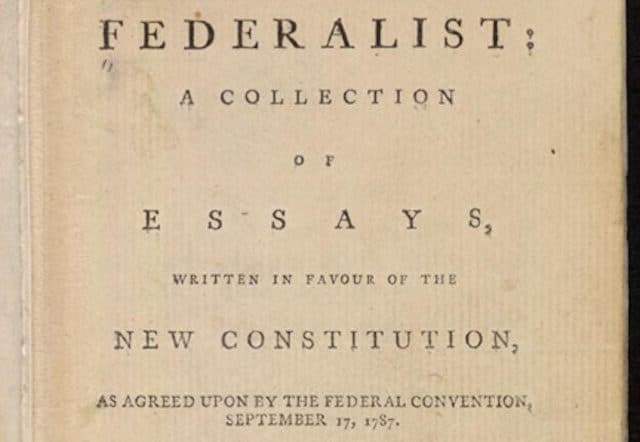

7. The Federalist Papers

In the last entry, we discussed how Hamilton wanted a central government and to form one, nine of the 13 states had to approve the U.S. Constution to ratify it. In order to generate support for the ratification, Hamilton came up with the idea of writing 25 letters to newspapers that argued for its ratification. To do this, he enlisted the help of statesmen John Jay and James Madison. All of the essays were published under the psydenom “Publius.”

However, instead of writing 25 letters, between October 1787 and May 1788 they actually wrote 85 essays. Hamilton wrote two-thirds of them – 51 in all; Madison wrote 29 (three of which were possibly co-written by Hamilton), and Jay wrote 5. What a slacker.

Then on June 21, 1788, New Hampshire became the ninth state to approve the Constitution, offically ratifying it.

6. He Was Involved in a Sex Scandal

In the summer of 1791, Alexander Hamilton was 34 (really 36) and living in Philadelphia with his wife and children. At the time, he was the secretary of the United States Treasury. One day, a 23-year-old woman named Maria Reynolds knocked on Hamilton’s door while his wife and children were out of town on vacation. Reynolds told Hamilton that her husband, James Reynolds, had abandoned her, but she was ultimately better off because he was a horrible man. She said that she didn’t have money and was wondering if Hamilton would help her out so she could travel to New York to stay with some family.

Hamilton agreed to help and told her that he would bring her the money that night. That evening, Hamilton went to her house, and then they went into her bedroom. Presumably that’s when Marvin Gaye stepped out of a time machine to set the mood, and Hamilton realized that “other than pecuniary consolation would be acceptable.”

Hamilton and Maria carried on the affair into the fall, but in the winter her husband James returned home and discovered the adultery. So James wrote a letter to Hamilton accusing him of breaking up a happy marriage. James also wrote that it was clear that Maria loved Hamilton and not him, so Hamilton could visit his wife every time that he left town, if Hamilton were to pay him $1,000. Hamilton agreed and paid. Maria would then tell Hamilton when James was leaving town, and then Hamilton would visit her. After the visits, James would write to Hamilton reminding them that they are friends, and then he would ask for some money, usually around $30 or $40. It’s believed at this point Maria was involved in her husband’s scam.

In November 1792, James Reynolds was arrested for a different financial scam and asked Hamilton for help. Hamilton refused, but word got around quickly that Reynolds had dirt on Hamilton. Three Congressmen (James Monroe, Frederick Muhlenberg, and Abraham Venable) visited James in prison and Maria at home. The couple told the Congressmen that Hamilton was a homewrecker who forced James to share Maria.

Monroe and Muhlenberg confronted Hamilton and he admitted to the affair and paying James the extortion money. He also showed them the letters. Monroe and Muhlenberg realized that Hamilton was just guilty of an affair and decided not to make it public, but they didn’t keep it secret. Monroe gave Hamilton’s main political adversary, Thomas Jefferson, a copy of a letter Maria sent to Hamilton.

The affair may have stayed quiet had it not been for the fact that Hamilton forgot the first rule of accusing other people of nefarious deeds, which is that people who live in glass houses shouldn’t throw rocks. In 1796, a year after Hamilton stepped down as secretary of the treasury, he wrote an essay questioning the morality of Jefferson’s personal life.

Then in 1797, a Republican muckraker named James Callender published The History of the United States for 1796. The book not only featured the letters between Reynolds and Hamilton, but it also accused Hamilton of being a part of the financial scam for which James had been arrested.

A financial scam would have been disastrous for Hamilton and also quite possibly for the fledgling American Treasury, because Hamilton was the architect for early American fiscal policy. The problem was that if he denied both allegations and one could be proven, then it would make him look like a liar.

Without another option, Hamilton admitted to the affair and published his own pamphlet explaining that he was the victim of an elaborate scam. He was guilty of making bad choices, but he was not involved in the scam. While people believed him, his reputation took a hit and it humiliated both Hamilton and his wife, Elizabeth, who was from a prominent New York family. Despite the scandal, Elizabeth ultimately stayed with Hamilton. However, she always blamed Madison, who would go on to become the fourth President, for the scandal.

The Reynolds’ filed for divorce and Maria was represented by none other than future Vice President Aaron Burr.

5. He Founded The New York Post

In the Presidential election in 1800, the candidates were Thomas Jefferson, who was the Democratic-Republicans candidate, and then-President John Adams, who was the candidate from the Federalist Party. The Federalist Party was the first American political party and it was based on Hamilton’s fiscal policies. They promoted a strong national government, loose interpretation of the Constitution, and a harmonious relationship with Britain. The Democratic-Republican party was the first opposition party and they pretty much wanted the opposite. They wanted more state rights and a more strict interpretation of the Constitution.

Hamilton was troubled that Jefferson won the election in 1800, so in November 1801, he founded The New York Post, which was originally called The New York Evening Post, with a $10,000 investment. The newspaper was obviously anti-Jefferson and anti-Democratic-Republicans.

The newspaper is still in print today. It was purchased by Rupert Murdoch in 1976, and it’s terrible. As comedian John Mulaney says, “I like reading the New York Post because reading the New York Post is like talking to someone who heard the news, and now they’re trying to give you the gist.” Hopefully that isn’t how Hamilton envisioned its legacy.

4. He Worked With Andrew Burr

The first recorded murder trial in the United States was called the Manhattan Well Murder. The case revolved around a young unmarried couple named Levi Weeks and Elma Sands. Weeks lived in New England, but moved to New York to work for his brother as a carpenter. In July 1799, he moved into a boarding house run by the aunt and uncle of Elma Sands. Soon, Weeks and Sands were meeting up in secret at night.

Trying to avoid getting in trouble for fooling around without being married, and possibly because Sands was pregnant, the couple got engaged on December 22, 1799. That night, they went out, and only Weeks returned home. He said that he didn’t know where she was and that he had simply lost track of her. A few days later, her body was found at the bottom of a well.

A short time later, the Grand Jury indicted Weeks. Weeks’ brother was a prominent citizen and he hired three of the best lawyers in the city: Henry Brockholst Livingston, Alexander Hamilton, and… Aaron Burr. The trial started on March 31, 1800, and went all the way until 2:00 am the next morning. The jury spent five minutes dilberating and came back with an acquittal.

The jury was criticized for the verdict and Weeks became a social pariah. After the trial, he was forced to move away from New York City.

3. He Lost His Son in a Duel

Obviously, Hamilton wasn’t enthusiastic about Thomas Jefferson’s win in 1800, but no matter how unhappy he was about the election, he accepted the results. After all, he was one of the Founding Fathers, and to suggest otherwise would have been very insulting. On July 4, 1801, a 27-year-old lawyer named George Eacker, a supporter of Jefferson, gave a speech at Columbia University, where he claimed that Hamilton wanted to take the Presidency by force and suggested that he preferred the monarchy over democracy.

Hamilton’s oldest son, 19-year-old Philip, read about the speech in the newspaper and four months later, he and a friend named Richard Price were at the theater when they spotted Eacker in one of the boxes. The two young men, who were possibly drunk, stormed the box and started to insult Eacker. They later got into an argument in the lobby. Eacker supposedly called the two boys “damned rascals.”

Later that night, Price sent a letter to Eaker demanding a duel and Philip sent a similar letter a short time later. Eacker agreed to both duels. First up was Price. He and Eacker dueled on November 22, 1801. Both missed, and according to the terms of the duel, honor was satisfied. The next day, Philip and Eacker met at the dueling grounds in Weehawken, New Jersey, just across the Hudson River from New York City. Duels were held there because they were illegal in New York, but not in New Jersey.

Both Eacker and Philip fired, but only Philip was hit. He spent a day in agony and then died. His death devastated the Hamilton family. One of his sisters had a nervous breakdown and Hamilton was so stricken with grief that he could barely stand. Yet this death wouldn’t stop a similar tragedy from unfolding just three years later.

2. The Infamous Duel

The roots of the duel that would claim the life of Alexander Hamilton can be traced back to the 1800 election. At the time, there was a flaw in the Constitution of the United States, which led to a unique political situation. Members of the electoral college were supposed to vote for two people for President. The problem was everyone voted for the same two men for the Democratic-Republican party: Thomas Jefferson, and the man he asked to be his running mate, Aaron Burr.

Hamilton, who was the inspiration for the Federalist Party and one of its most important members, thought that Jefferson was the lesser of two evils, so he helped campaign for Jefferson. However, then-President John Adams and the other Federalists wanted Burr to be the Presidential candidate. After several rounds of voting that resulted in ties, Jefferson finally won the vote for Presidential candidate and Burr became the Vice Presidential candidate.

After Jefferson defeated Adams for the Presidency, Jefferson didn’t trust Burr because of what happened in the lead up to the election. Burr was left out of meetings and given very little power. When Jefferson ran for re-election in 1804, Burr was dropped from the ticket.

Instead, Vice President Burr decided to run for governor of New York in 1804, and he lost. After the loss, Burr read about Hamilton trashing him in the newspaper, and he may have thought that Hamilton caused him to lose a second election.

Hoping to restore his reputation and regain any respect that he lost because of Hamilton, Burr challenged him to a duel. Things escalated between the two men and it became impossible for either of them to back out.

At dawn on July 11, 1804, Burr (who was still Vice President) and Hamilton met at the same dueling grounds where Hamilton’s son was mortally wounded three years earlier. The men drew their guns, Hamilton fired and missed, then Burr fired and he hit Hamilton. Hamilton died the next day at the age of 49 (his real age).

After the duel, Burr went back to Washington and even though he was wanted for murder in New York and New Jersey, he managed to serve out the rest of his term as Vice President and was never tried for the killing. The duel, however, did lead to the death of Burr’s political career. After living for many years in obscurity, Burr died in 1836.

1. He Left His Family in Debt

One would think that, since Hamilton was a lawyer who created the foundation of the American economy and served as the Secretary of the Treasury, he would be very wealthy. After all, he is one of only two non-Presidents on American currency, so he must have at least been good with money. That is certainly what James Madison and Thomas Jefferson wanted people to think. They actually perpetrated the rumor after his death that he was corrupt and used his position as Secretary of the Treasury to make himself a very wealthy man.

However, when Hamilton died, he left his family with a lot of debt because he wasn’t corrupt and didn’t cheat the system. Also, by serving as Secretary of the Treasury, he made a lot less than he would have if he was a lawyer. He probably would have made more money after his political career was over had he not been killed in the duel.

Things got to be so bad for the family that after Jefferson’s term was over, Elizabeth Hamilton was forced to ask Congress for the money and the land that Hamilton had been owed for serving in the Revolution, which he had previously forfeited.