Since its inception as a country, America has produced a relentless fighting spirit, resulting in astonishing acts of valor on all corners of the globe. The task of quantifying courage, however, can be a difficult assignment that involves several factors, including different branches of military, date of the commendation, discontinued and/or upgraded medals, and the prestige of an award.

As a measuring stick, it’s helpful to understand the basic hierarchy of the most important American citations for bravery. Heading the class is the Congressional Medal of Honor, an award dating back to 1862 during the Civil War whereby Congress authorized the President to present the citation. The Distinguished Service Cross (DSC) falls next in line followed by the Navy Cross — which can’t be won by all soldiers — and where the slippery slope of “Most Decorated” comes into question. As a rule of a thumb, the Silver Star and Bronze Star both carry significant weight, as well as the Purple Heart, a medal given to those wounded in the line of duty.

Please note this list is by no means definitive or in any particular order, but merely attempts to provide a consensus of highly decorated U.S. soldiers from all major conflicts. Also, one glaring omission is Douglas MacArthur, who technically ranks highest on many polls using an assortment of arbitrary point systems. However, allowing a 5 Star General (and a man known as “American Caesar”) to sit atop the mountain is kinda like Walt Disney giving himself the honorary key to the Magic Kingdom.

10. Daniel Daly

Daly is one of a select group of soldiers to earn the Medal of Honor twice — and would have probably earned a third had it not been for a petty ruling at the time, setting the limit at two. Nonetheless, the battle-hardened Marine is best remembered for his valor in WWII at the Battle of Belleau Wood, where under intense fire he famously rallied his men, shouting “Come on, you sons of bitches, do you want to live forever?!” The 44-year-old veteran settled for the Distinguished Service Cross, adding to his pile of medals that also included a Navy Cross, a Silver Star, Médaille Militaire, and Croix de Guerre.

The son of Irish immigrants, Daly stood only 5-foot-6 and weighed only 132 pounds, but earned a hard-fought reputation of someone who could scrap and never backed down — a resolve that served him well throughout his life. He first joined the Marines in 1899, and took part in the Boxer Rebellion in China, a mostly forgotten war in which American troops found themselves besieged by local “boxer” militia forces. Pvt. Daly, armed with only a bolt-action rifle and a bayonet, defended a vulnerable position single-handedly against repeated Chinese attacks. By the time reinforcements arrived the following morning, they found his position littered with enemy dead bodies. Throughout the ordeal, the attackers had yelled “Quon-fay,” at Daly, a term meaning “a very bad devil.” For his conspicuous gallantry on August 14, 1900, he received his first Medal of Honor.

Fifteen years later, Gunnery Sergeant Daly earned his second MOH in Haiti while combating the local Cacos rebels in a conflict designed to protect American business interests commonly known as the “Banana Wars.” Daly’s superiors had offered him an officer’s commission several times, but he always declined, stating “I would rather be an outstanding sergeant than just another officer.”

Perhaps Daly’s greatest accolade came from fellow double Medal of Honor recipient, Major General Smedley Butler, who called Daly the “fightingest Marine I ever knew.”

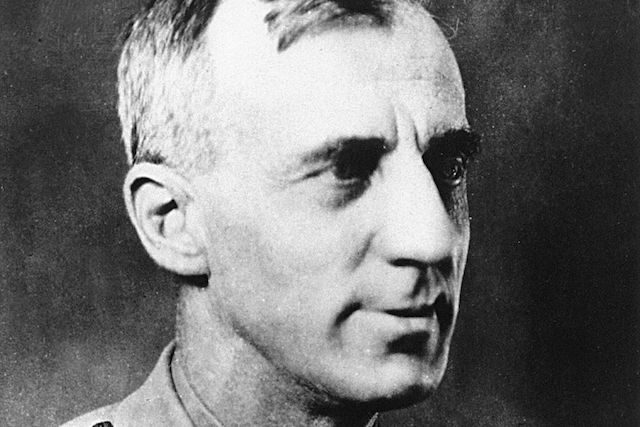

9. Smedley Butler

At the time of his death in 1940, Butler — aka “The Fighting Quaker” — had achieved the exalted status as the most decorated Marine in history. An impressive accomplishment considering the Corp’s core values of Honor, Courage, and Commitment — and fighting to the death wherever American soldiers are needed.

During his 33 years of service to Uncle Sam, Major General Butler earned numerous citations, including two Medals of Honor, Marine Corps Brevet Medal and The Order of The Black Star. However, Butler is also a fascinating study in contrast as a man who wore a neck-to-navel Marine Corp tattoo on his chest, and later became an outspoken critic of American war profiteering and imperialism.

Born and raised in West Chester, Pennsylvania by Quaker parents, Smedley Butler possessed a streak of rebellion and sense of adventure at an early age. He joined the Marines just prior to his 17th birthday and eventually served in Cuba, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Haiti. He also fought in the Mexican Revolution at Battle of Vera Cruz, where received his second MOH.

Known for his leadership and undying loyalty to those under his command, he fought on three continents before retiring from the military in 1931. He then began his second career as an advocate for pacifism, giving lectures around the country which later served as the basis for his book, War is a Racket.

His message didn’t mince words regarding the injustice he could no longer stomach: “At least 21,000 new millionaires and billionaires were made in the United States during the World War… How many of these war millionaires shouldered a rifle? The general public shoulders the bill. And what is this bill? …Newly placed gravestones. Mangled bodies. Shattered minds… For a great many years, as a soldier, I had a suspicion that war was a racket; not until I retired to civil life did I fully realize it.

8. Edward A. Carter

In 1992, the Secretary of the Army commissioned an independent study to identify African-American soldiers whose acts of valor might have been denied the Medal of Honor due to prejudice in both World Wars. Following completion of the report, Sgt. Edward A. Carter (1916-1963) had been identified and recommended for the country’s highest award.

In 1997, President Clinton presented Carter’s posthumous Medal of Honor to his son, Edward Allen Carter III. His citation in part reads as follows:

On 23 March 1945, near Speyer, Germany, while serving with Company #1, 56th Armored Infantry Regiment, 12th Armored Division. When the tank on which he was riding received heavy bazooka and small arms fire, Sergeant Carter voluntarily attempted to lead a three-man group across an open field. Within a short time, two of his men were killed and the third seriously wounded. Continuing on alone, he was wounded five times and finally forced to take cover. As eight enemy riflemen attempted to capture him, Sergeant Carter killed six of them and captured the remaining two. He then crossed the field using as a shield his two prisoners from which he obtained valuable information concerning the disposition of enemy troops.

Born in Los Angeles on May 26, 1916, to missionary parents, Carter’s path to becoming a national hero involved several foreign stops, including India and China. Eschewing his family’s strict, non aggression beliefs, he ran away from home at 15 and enlisted in the Chinese Nationalist Army to fight against invading Japanese forces; he later wound up in Europe, fighting for the Loyalists in the Spanish Civil with the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, an integrated volunteer unit of mostly American volunteers dedicated to fighting fascism.

Upon his return to the United States, Carter joined in the Army in 1941 as a sergeant, but soon found himself subjected to racism within the segregated U.S. military. Making matters worse, an intelligence officer at Fort Benning, Georgia, “deemed it advisable” to put Carter under surveillance because of his background in “communist” China and fighting on the side of the”socialists” in Spain.

Carter eventually shipped out to Europe in 1944 battle-tested and ready to fight; upon arrival in the ETO, he was assigned to George S. Patton’s Third Army, serving briefly as one of the general’s personal bodyguards. By spring of the following year, and with the end of the war in sight, Carter finally saw combat, but had to accept a demotion to private because he wasn’t allowed to command white troops. That would all change after his heroic actions on March 23, 1945, and saw his sergeant stripes restored for the remainder of the war.

But when Carter attempted to re-enlist prior to the Korean War, his “suspect” background led to being discharged without explanation. Unfortunately, the fact that he had been awarded the Distinguished Service Cross (later upgraded), Purple Heart and Bronze Star fell on deaf ears — and closed minds. Disheartened, he moved back to California, where he later passed away in 1963 at the age of 47 from cancer, a condition his doctors partially attributed to shrapnel still in his neck.

Although Carter was originally buried in West Los Angeles, his remains have since been moved to their rightful final resting place at Arlington National Cemetery.

7. Robin Olds

Gravitas. A nuanced word that can be difficult to describe but easily understood when looking a photo of triple ace (5 kills = ace) fighter pilot, Robin Olds. He not only looked the part of a superhero — but actually lived it with his lead-from-the front swagger and natural born talent. Not surprisingly, he even married a movie star and pin-up icon, Ella Raines, to complete the picture. However, for all of his many outstanding attributes, it was his non-regulation handlebar mustache dubbed “bulletproof” that would achieve rock star status. The whiskers also pissed off his superiors — which was exactly the point for the rebellious fighter jock who had it all.

Raised in a military family, Olds’ father had been an aviation pioneer in WWI and eventually rose to the rank of a Major General in the Army Air Corp (precursor to the U.S. Air force). The younger Olds attended West Point where he became a football All-American before earning his wings as a pilot in WWII. Shortly after arriving in France in 1944, he earned the first of his 12 confirmed kills during the war, flying P-38s and Mustang P-51s.

He later participated in transcontinental jet races and flew with the air force’s first aerobatic demonstration team, further honing his flying skills and leadership qualities. But his outspoken demeanor and demands for improved training and equipment saw him branded as a troublemaker and iconoclast by higher-ranking officers, who kept him grounded during the Korean War. Olds nearly walked away from the military altogether, but eventually took command of the 8th Tactical Fighter Wing in Vietnam.

His finest hour came in 1967 when he devised a plan labeled “Operation Bolo,” in which F-4 Phantoms used radar-jamming devices to lure (Soviet-made) MiG-21s into a trap. When North Vietnamese fighters responded by attacking what appeared to be slower-moving aircraft, the faster F-4s downed seven enemy jets, including two by Olds in the what became the biggest air battle of the war. He would later bag two more MiGs, giving him a total of 16 kills in his career. Always the outlaw, he stopped logging his combat missions at 99 to avoid reaching the limit that would rotate him back home. He also didn’t want to be used as a publicity tool, and avoided adding more kills to his already impressive record.

By the time he finally retired from the military, now Brigadier General Olds had been decorated 54 times, including the Air Force Cross (USAF’s highest honor), two Air Force Distinguished Service Medals, four Silver Stars, six Distinguished Flying Crosses, Legion of Merit and Croix de Guerre.

As for that infamous ’stache, Olds cemented his legend this way: “It became the middle finger I couldn’t raise in the [public relations] photographs,” he said. “The mustache became my silent last word in the verbal battles … with higher headquarters on rules, targets and fighting the war.”

6. James F. Hollingsworth

Articles and books written about Lt. General Hollingsworth often describe his unfiltered character as “profane,” “brash,” and “irreverent.” But anyone who fought alongside him during his storied 36 years as a fighting machine held a deep respect for the gruff Texan, whose fearlessness on the battlefield was as large as the state that produced him. From WWII to Vietnam and every conflict in between, Hollingsworth left his mark, earning three Distinguished Service Crosses, four Distinguished Service Medals, four Silver Stars, three Legion of Merit medals, three Distinguished Flying Crosses, six Purple Hearts, and four Bronze Stars.

After graduating from the Agricultural and Mechanical College of Texas (now Texas A&M) in 1940, he accepted a commission in the U.S. Army as a second lieutenant. He would participate in seven major campaigns in WWII, rising from platoon leader to battalion tank commander in Gen. George S. Patton’s Third Army. During a legendary engagement near the Elbe River in Germany, then Major Hollingsworth encountered well-entrenched German defenders. Seizing the moment befitting of fiery nature, “Holly” lined up his 34 tanks and loudly gave the command, “Charge!” As expected, the terrified Germans broke and ran.

Hollingsworth later added to his colorful reputation (and vast collection of medals and commendations) as the assistant division commander of the 1st Infantry (“Big Red One”) Division in 1966. In Southeast Asia, he became known by the radio call sign “Danger 79er” and famously once told a reporter that it felt “real good to be killin’ hell out of the communists.” Hollingsworth would be reprimanded by Army brass for his cavalier raids that included participating in search and destroy missions aboard his helicopter.

5. Eddie Rickenbacker

Prior to becoming America’s most decorated ace pilot in WWI, “Fast Eddie” had been a champion race car driver and set a then world record of 134 miles-per-hour. He later swapped uniforms and registered 26 kills in the skies over Europe in just nine months of aerial combat. Although the infamous Manfred (“The Red Baron“) von Richthofen is credited with more downed aircraft (80), most military historians agree that Rickenbacker’s expert stick and throttle skills, and natural born killer instincts put him in a class all by himself.

As one of eight children born to Swiss immigrants in Columbus, Ohio, Rickenbacker’s mercurial rise as a national hero is a remarkable tale of talent and determination. When American officially entered WWI in 1917, Rickenbacker enlisted in the Army and became a chauffeur on General John Pershing’s staff. “Fast Eddie” set his sights on becoming a pilot in the newly formed Army Air Service, but at 26 years old, he exceeded the age limit by two years and also lacked the formal education required to fly. But with perseverance and a display of undeniable skills, Rickenbacker eventually earned his wings and became commanding officer of the 94th Aero “Hat-in-the-Ring” Squadron. Once airborne, he wasted little time establishing his reputation as a lethal fighter.

He would receive the Medal of Honor for actions on September 25, 1918, during a voluntary solo patrol behind enemy lines in France. Rickenbacker attacked a squadron of German planes (including five Fokker D.VIIs) from behind the sun, plunging his Spad biplane into a power dive, a maneuver that became his signature move on the unsuspecting enemy. After shooting two of the planes, he returned to base for a well-deserved hero’s welcome. In addition to his MOH, Rickenbacker received seven Distinguished Service Crosses and the French Croix de Guerre.

Incredibly, his life after the war would prove far more dangerous as he experienced two near-fatal plane crashes and became lost at sea for 24 days. Somehow, he managed to survive and went on to become a highly successful businessman and the CEO of Eastern Airlines.

4. Lewis “Chesty” Puller

Whether he acquired his nickname for being the cockiest rooster in the yard or simply from all the medals pinned to his chest, this Marine’s Marine achieved near-mythical status during his 37 years of wreaking havoc on the enemy. Puller’s quest for military glory began at an early age while growing up near the hallowed grounds of northern Virginia, where he listened to old war stories about Confederate legends such as Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson.

Puller briefly attended Virginia Military Institute before dropping out to “go where the guns are” and fulfill his dream of becoming a career soldier. After missing out on WWI, he experienced his first taste of combat in Haiti and later earned the first of his five Navy Cross medals (the most ever awarded) while fighting a guerrilla insurgency in Nicaragua. His personal motto of leading by example became the stuff of legend, taking part in some of the bloodiest fights in WWII and the Korean War. At the Battle of Guadalcanal, Puller became wounded by sniper fire and shrapnel (which only made him angrier) as he repeatedly rallied his vastly outnumbered men against a barrage of Japanese attacks.

Lt. General Puller eventually surpassed Smedley Butler to become the most decorated Marine — despite never receiving a Medal of Honor — an egregious snub that remains a hotly debated subject with military experts and historians alike. Puller’s heroic exploits and unwavering loyalty to the Corps are just a few reasons why to this day, Marines at boot camp typically end each day, declaring “Good night, Chesty Puller, wherever you are!”

3. Audie Murphy

The inscription for the Medal of Honor begins “For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of life above and beyond the call of duty.” A fitting introduction indeed, for the larger-than-life figure of Audie Murphy. Ironically, this pint-sized Texan (he stood 5-foot-5 — and that’s being generous) was repeatedly rejected for military service due to his physical shortcomings. Finally, the Army said yes, and the man called “Baby” proceeded to kill 250 enemy soldiers to become commonly known as the most decorated soldier in WWII.

In January 1945, a particularly brutal firefight near the German village of Holtzwihr, Murphy produced one of greatest acts of courage in American military history. With his company in retreat and facing certain annihilation from enemy artillery, the fearless 19-year-old climbed on top of a burning M-10 tank, tossing dead bodies aside and commandeered a .50 caliber machine gun. Despite being severely wounded, he held off a steady wave of German infantry and tanks for over an hour — actions for which he would later receive the Medal of Honor.

After the war, he wrote a best selling memoir, To Hell and Back, and also became a Hollywood movie star. And yes, he even did his own stunts. In addition to his Medal of Honor, he earned a Distinguished Service Cross, two Silver Stars, the Legion of Merit, two Bronze Stars, three Purple Hearts, the French Fourrager, the French Legion of Honor, Croix de Guerre with Palm and Silver Star, and the Belgian Croix de Guerre.

2. David Hackworth

Some boys dream of running away to join the circus. David Hackworth left home at 14 in search of a war. Incredibly, he would earn 91 medals as one of the most decorated soldiers who ever lived, including two Distinguished Service Crosses, 10 Silver Stars, 8 Bronze Stars, and 8 Purple Hearts. He won a battlefield commission at 20 to become the youngest captain the Korean War and was the youngest full bird (colonel) in Vietnam. Movie buffs will also appreciate that the man known as “Hack” reputedly served as inspiration for the rogue character of Colonel Kurtz in Francis Ford Coppola’s Vietnam War epic, Apocalypse Now.

After catching the tail end of WWII as a Merchant Marine, he joined the Army and rose quickly through the ranks. He commanded the “Wolfhound Raiders,” an all-volunteer regiment in Korea, where during an intense firefight he was shot in the head but refused to quit fighting. Typical never-say-die “Hack.” By the time the next war rolled around, he had become an expert on guerrilla warfare tactics and would co-author the Veteran Primer, a manual on counterinsurgency still in use today.

But as the war in Vietnam dragged on, Hackworth became more rebellious and independent, as well as increasingly frustrated with the Pentagon. In a 1971 interview with ABC-TV, he even went as far as to say that the war couldn’t be won. His candor caught American top brass off guard — after all, they expected to see his star continually rise — or as Coppola later put it, “He was being groomed for one of the top slots in the corporation. General, Chief of Staff… anything.” Following Hackworth’s controversial statements, the Army floated the possibility of a court-martial, but the colonel was eventually allowed to resign with an honorable discharge.

He then turned to writing and journalism, penning his best-selling autobiography About Face: The Odyssey of an American Warrior. Additionally, he founded Soldiers for the Truth, an advocacy group dedicated to military reform, both in terms of improved capability and treatment of personnel.

1. Robert L. Howard

John Wayne spent most of his career portraying fictional heroes on the silver screen. Colonel Robert L. Howard spent most of his career portraying a hero on the battlefield: himself — and even found time to appear in two of the Duke’s films, The Longest Day and The Green Berets. But for someone like Howard, the word “hero” doesn’t even begin to describe the enlisted man from Opelika, Alabama, who became the most decorated soldier of the modern era.

For those not familiar with Howard’s remarkable story, there’s a good reason: most of his service involved highly classified, covert ops behind enemy lines. In his extraordinary 36 years in uniform, he became a Paratrooper, Pathfinder, Airborne Ranger, Green Beret, and finally a full colonel before his retirement in 1992.

As a member of Special Forces, he served in the top-secret MACV-SOG (Military Assistance Command Vietnam Studies and Observations Group), which ran cross-border operations along the Ho Chi Minh Trail in Laos, Cambodia, and North Vietnam, and conducted some of the most gutsy and dangerous missions of the war.

His duty included five tours in which he received eight Purple Hearts (although he was wounded 14 times) and was nominated for the Medal of Honor on three separate occasions during a thirteen-month span. The first two actions resulted in a Distinguished Service Cross and a Silver Star, but his third act of “conspicuous gallantry” earned him the Medal of Honor during involving a mission to rescue a fellow soldier in Cambodia.

Howard passed away in 2009 at the age of 70 and was buried with full honors at Arlington National Cemetery. As of January 2019, Hollywood is still trying to figure out who could convincingly play this real-life Rambo.

6 Comments

Question: why is Captain Bobbie E Brown not 1 of the 10? Captain Brown served for 30 years (1922-1952) and for his actions in North Africa, invasion and landing in Sicily, landing on Ohama bench 6 June 1944 and then fighting up theough France to Oct 1944 where his heroic actions earned him a MOH, he added it to his 2 SCs, BSV and because of his 13 wounds in three separate campaigns he was awarded with 8 purple hearts…

There is no such thing as the “Congressional Medal of Honor.” It’s simply the Medal of Honor. And, concerning Daly, #10 in your list, the Battle of Belleau Wood was NOT in WWII but WWI. His uniform alone should have told you that. I suggest you stay away from topics the history behind which you apparently don’t know.

Funny story about Chesty Puller – he was one of the first soldiers to test out the newfangled “flame-thrower.” Upon trying it out, he asked the most badass question ever uttered after using a flamethrower. “Where do you put the bayonet?”

Another serial killer list. Cool.

Richard Cavazos, Hispanic American officer who won Distinguished Service Crosses in the Korean War with the Puerto Rican Nation Guard Division and in the Vietnam War with the 1st Infantry Division. He set many firsts as a Hispanic American officer, commanded the 9th Infantry Division, was an early advocate of the National Training Center, and retired as FORSCOM commander. General Norman Shwartzkopf called him one of the finest leaders he had ever known.

You left out Bud Day.