For many of us Mars represents hope. From scientific discoveries (e.g. living organisms against all the odds) to the promise of colonization, the Red Planet may be key to our survival. Certainly as life on Earth grows steadily more precarious, our second closest neighbor seems to present a viable alternative—even if some think that’s crazy.

Here are some facts you may have missed…

10. Scientists observed a Martian “civilization” just last century

The astronomer William Herschel made some important observations of Mars, including its rotation period and the seasonal variation of its ice caps. But, like many of his era, he also worked under the assumption that the planet was teeming with life. He saw the dark areas as oceans and observed vegetation on the supposed landmasses. He even suggested that intelligent Martians “probably enjoyed a situation similar to our own.”

That was in the late 1700s, but it was an idea that persisted for centuries. Hence when the Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli’s description of canali (channels) on the surface was translated into English as “canals,” people imagined waterways constructed by a human-like society on Mars. And whatever he might have thought of the phenomena himself, his own maps only served to support this assumption—resembling as they did a sprawling port city sectioned into districts by canals. Others’ maps suggested even more of a man-made Martian Venice.

Even in the 20th century, the American astronomer Percival Lowell praised the Martians’ ingenuity. According to him, the canals (which he built a state-of-the-art observatory to view) were likely constructed to transport water from the poles to the plains—perhaps in a bid to save life on Mars from extinction. They were evidence, he wrote, of “a mind of no mean order … a mind certainly of considerably more comprehensiveness than that which presides over … our own public works.”

By Lowell’s time, most scientists saw these grooves in the landscape as a natural geological phenomenon. But the idea of an advanced Martian civilization persisted in the popular imagination. The science fiction author Edgar Rice Burroughs was among those to encourage this belief, portraying a developed (albeit dying) world of majestic cities, warring humanoid races, and a fantastic bestiary of eight-legged horses, ten-legged dogs, and giant, four-armed white apes so ferocious they were among the leading causes of death on the planet.

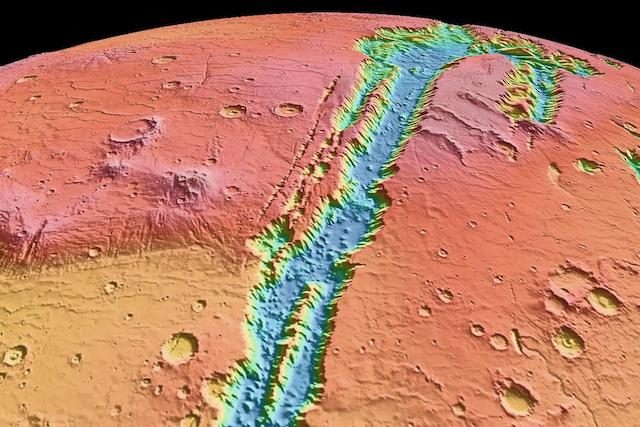

9. Valles Marineris is the grandest canyon in the Solar System

Valles Marineris cuts a deep scar across 20% of the circumference of Mars, extending an incredible 2,500 miles around the planet. It begins in the maze-like valleys of the Noctis Labyrinthus (‘labyrinth of the night’) in the west and abates in the smooth Chryse Planitia (‘golden plain’) to the northeast.

373 miles across in places with a maximum depth of roughly 5.5 miles (or 30,000 feet), it’s decidedly grander than the Grand Canyon on Earth. That trench extends a mere 497 miles in length, measures up to 18.6 miles across, and is no more than 6,000 feet deep.

The Valles Marineris is thought to have started as a crack in the surface of Mars, dating back to the cooling of the planet as it formed. This assumption is based on evidence of geological processes such as lava flows, collapse pits from rushing water and floods, and glacier carving.

8. Global dust storms encircle the planet

Even regular dust storms on Mars are intense, lasting for weeks at a time and covering continent-sized areas. But once every three Mars years (5.5 Earth years), a mammoth, months-long dust storm encircles the entirety of the globe.

As impressive a sight as that is, Martian dust storms are nowhere near as powerful as storms can get on Earth. In fact, since winds don’t exceed 60 miles per hour, they’re not even strong enough to qualify as Category 1 hurricanes (the weakest, entry-level category). There’s also less pressure on Mars anyway, so it would take considerably more force to create the same effect as on Earth. Simply put, Matt Damon probably wouldn’t have been stranded by the storm at the beginning of The Martian; indeed, the astronauts wouldn’t have left in the first place.

You can actually listen to some of the more average Martian winds here. Recorded by NASA’s InSight lander in Elysium Planitia on Dec 1, 2018, the pressure sensor recordings were so weak they had to be sped up by a factor of 100 just to be audible.

Martian winds aren’t completely harmless, though. Dust particles are electrostatic, so they stick to surfaces upon contact. This is why Mars rovers look so filthy. Electrostatic dust is also problematic for mechanical moving parts, as well as solar panels. The daily sweeping of solar panels in The Martian to ensure their optimal efficiency was therefore something the movie got right.

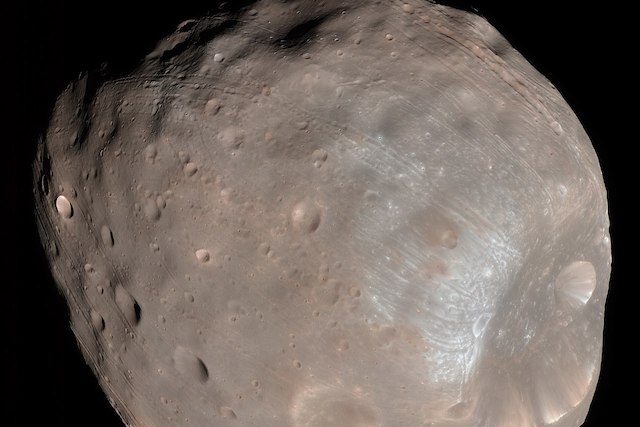

7. The moons of Mars have different fates

Phobos (fear) and Deimos (panic) are named for the sons of Ares—the Greek god of war, aka Mars to the Romans—who pulled their father’s chariot into battle. But they’re not quite as imposing as they sound. Phobos is a mere 43 miles around and Deimos is just 24 miles. Because of their irregular shapes, they’re actually thought to be captured asteroids caught in Mars’s gravitational pull. And because of their diminutive size, they both have very little gravity of their own. On Phobos, for example, you could easily throw a baseball into escape velocity, while on Deimos you could ride a bike off a hill into space. (Panic indeed!)

The closer to Mars of the two is Phobos, orbiting the planet in just under a third of a day at a distance of 9,377 kilometers. Deimos takes roughly one and a quarter days to complete its orbit, perambulating at a distance of 23,436 kilometers. By way of comparison, the Earth’s moon, at 384,400 kilometers, has an orbit of almost a month (which is of course why we call it a month in the first place).

Phobos’s great speed means it’s actually getting closer and closer to Mars with each orbit. Eventually it’ll reach the Roche Limit, an orbit so close to the planet that tidal forces pulling on the near and far sides of the moon are so powerfully opposed they will simply break Phobos into pieces. When that happens, it will probably form a ring around Mars—a ring that will later rain down upon the equator. Colonists needn’t worry too much, though; this semi-apocalyptic scenario isn’t expected to happen for another 30-50 million years.

Deimos has a rather different fate. Similar to our own moon, it’s gradually getting further away from the planet and eventually it will drift off into space.

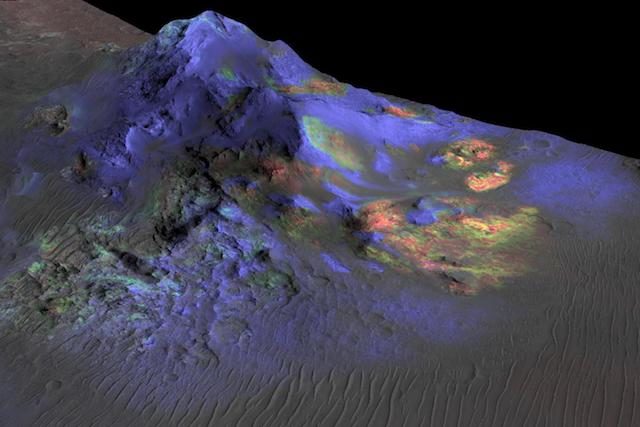

6. Olympus Mons is the biggest volcano in the Solar System

With a diameter of 374 miles, Olympus Mons is roughly the same size across as Arizona. Towering 16 miles high, it’s also three times taller than Everest. In fact, Olympus Mons is so tall you could effectively hike into space.

One reason for its vast proportions is Mars’s different geology. On Earth, crustal plates move over stationary hotspots to form new volcanoes and render old ones obsolete. But on Mars, the crust doesn’t move. Instead, lava piles up over billions of years in one spot. And the lower gravity means the resulting mass weighs less than it would on Earth, allowing volcanoes to get much, much larger without collapsing.

Olympus Mons is just the hugest of several huge volcanoes on Mars—all in the region of Tharsis. The next tallest, at 12.4 miles in height, is Arsia Mons, followed by Ascraeus Mons (9.3 miles) and Pavonis Mons (8.7 miles). And it isn’t just the biggest volcano in the Solar System, but the biggest (known) mountain of any kind on any of the eight planets. Only the asteroid Vesta is home to a higher peak—and there’s only a 315-foot difference.

5. The Red Planet used to be blue

While notions of organized life on the surface of Mars have long since been quashed, we now know the planet has water. And billions of years ago, it almost certainly had rivers, lakes, and seas just like the Earth. Digital visualizations give us a glimpse of what this may have looked like—either from within the early Martian atmosphere or from without, looking at the planet from space.

In the latter case, a massive continent fills one side of the western hemisphere. The terrain ranges widely between glacial ice and tundra in the north and south, lush rainforests in the tropical and subtropical regions, and arid volcanic desert in the equatorial region around Mars’s iconic giant peaks. The other side is awash with a vast blue ocean, flowing inland via the Valles Marineris.

Although this image was created more to “trigger the imagination” than as an accurate scientific model, it certainly isn’t unrealistic. Clay samples collected on Mars are evidence of ancient riverbeds, for example, while eroded cliffs are thought to describe the coastlines of former oceans—or perhaps one giant ocean—incorporating the 4-5 kilometer-deep, 2,003 kilometer-wide Vastitas Borealis or ‘northern waste.’

Most of the water is thought to have frozen and evaporated as the atmosphere was stripped away by the Sun. And, unfortunately for those who believe an advanced civilization once thrived on the planet, this may have happened just hundreds of millions of years after Mars had only just formed.

4. Mars could be blue in the future

The Martian atmosphere is now so thin (0.6% the pressure of Earth’s at sea level) that if you were to stand unprotected on the surface, your saliva, tears, and the moisture in your skin, along with any fluid in your lungs, would immediately and painfully evaporate. Of course, you’d also be unable to breathe the 96% CO2 air or withstand (for very long) the average temperature of -81 °F. But if you did, there’s also the ever-present hazard of meteorites—space rocks passing intact through Mars’s ultra-scarce atmosphere.

And, as thin as it is at present, the atmosphere is still being lost into space, stripped away by solar winds at upwards of 100 grams per second. But even at this rate it’ll be another 2 billion years before Mars loses its atmosphere (practically) completely and ends up like the Moon or Mercury.

So there’s hope. The expectation is that at some point us humans will intervene, terraforming Mars by thickening the atmosphere and replenishing it to livable levels. There are a number of ways to do this, mostly involving the release of carbon dioxide locked up in ice and rocks. Orbital mirrors could be used to melt the polar ice caps, for instance, or thermonuclear bombs could be used to explode them, throwing dust into the air to further increase the greenhouse effect. Introducing gases like ammonia and methane would also help thicken the atmosphere. And the melted ice should naturally flow into oceans. Over centuries, the carbon dioxide could be converted to breathable oxygen by plants or even machines.

Another way could be to seed the planet with microbial life to create the conditions of primordial Earth, then gradually introduce plant and animal life.

However we recreate it, though, the atmosphere would again be sheared off into space for the same reason it’s being lost in the first place: Mars lacks the magnetic field required to hold on to it. Paraterraforming—the terraforming of specific regions rich in carbon dioxide and housing them under domes—may be the most realistic alternative. But, since any global atmosphere wouldn’t be lost for many millions of years anyway, there should be ample time to construct a sphere around the entirety of the planet, thereby containing the terraformed Martian atmosphere. A ‘shell world’ like this might feature artificial lights, hanging cities, and even gravity control—perhaps allowing humans to fly.

3. The new space race is well underway

Efforts to colonize Mars are frequently in the news these days. And, interestingly, they’re mostly being undertaken by private enterprises. This is encouraging given the amount of bureaucracy that hinders national space programs. Although NASA under Trump aims to get people there by the 2030s, for instance, subsequent administrations’ priorities may be different. The United Arab Emirates, which has relatively little in the way of bureaucratic red tape, may have a more realistic, albeit audacious, plan to house 600,000 in a new Martian city by 2117. But, like Russia (which planned to send humans there this year), they haven’t landed anything on Mars as yet—not even so much as a probe.

The private company Mars One famously put out a call for colonists in 2013—no experience required. And the company plans to establish an outpost on the planet by 2026, sending the first humans there in 2031. When they arrive, they’re expected to get to work setting up solar panels, food production units, and other essentials for long-term human survival.

Odds are in favor of SpaceX, though, which plans to get there much sooner. Assuming everything goes according to plan over the next few years, they could start building a propellant production plant on Mars by 2022. This would allow return trips and the establishment of viable long-term settlements (villages to become cities) from as early as 2025. SpaceX founder Elon Musk actually gives himself a 70% chance of moving there by then.

Ultimately, SpaceX intends to send millions of people to Mars. They don’t think it will be without problems (Musk assumes people will die), but they do believe that it’s well worth the risk. As they see it, Mars is just the first step. Long term, SpaceX’s Starship is envisioned as “an interplanetary transport system,” getting humans practically anywhere in the Solar System and setting up propellant production plants along the way.

2. Life on Mars won’t necessarily (or necessarily won’t) be bleak

Despite the differences (e.g. orange skies during the day and blue skies at sunset and sunrise), there are some striking similarities between Mars and Earth. A Martian day is just 40 minutes longer than ours, for instance, in contrast to a Venusian day that’s 242 days longer than ours (and actually longer than a Venusian year). And Mars’s axis is also tilted similarly to the Earth’s (25.19° to our 23°), resulting in comparable changes of season.

But life will obviously be hard for the colonists, at least in the early days. Even if they do get to make a return journey, they’ll probably have to stay for at least a couple of years just to make the months-long trip out worthwhile. And throughout this time they’ll be confined to small spaces with only brief and occasional walks on the surface.

Life will, however, (probably) get better in the long run. Indeed, it’ll have to if it’s to attract anywhere near the kind of numbers required to make colonization a success (unless people go there simply to get away from Earth). In late 2018, architects released a series of concept images for how life on the Red Planet might look. Although primarily built to withstand harsh radiation and dust storms, as well as the freezing temperatures, Martian homes, they say, will also have to be homely.

Family residences are envisioned as geodesic domes set back in protective caves, complete with soft lounging space and sentimental touches—like shag rugs depicting the Earth from space and cuddly toys for the kids. There’s also an inbuilt garage for a personal rover and a conservatory veranda with indoor garden space. Mansions for the more affluent have sleek, modular designs stacked into the sides of a crater and enormous plate glass windows to survey the otherworldly view. Apartment blocks, meanwhile, needn’t have windows at all. Instead, views could be on a live feed from the Martian surface or else programmed with views of Earth. Of course, virtual reality could allow for more immersive experiences of our home planet.

Looking to the longer term future, it’s interesting to note that humans born on Mars will likely be taller than average. The lower gravity (one third of Earth’s) will allow the fluid between their vertebrae to expand—just as it does for astronauts in space. So born-and-bred Martians will probably avoid visiting Earth at all, since it would be the equivalent of us visiting a planet with three times the gravity of our own. Someone weighing 160 pounds on Mars would suddenly weigh almost 500 pounds on Earth, making it difficult to move around and potentially causing bone problems.

1. There may be life on Mars right now

Because Mars lost its atmosphere and the majority of its water gradually, over a period of millions or billions of years, it’s possible—even likely—that life evolved to survive the increasingly inhospitable conditions.

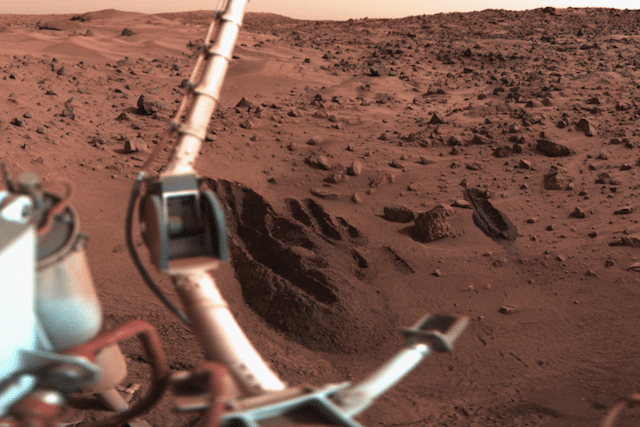

Back in 1975, the year before the first Viking lander returned data and samples from the surface, Martians were envisioned as ground-based and fungal in appearance. Nowadays, we understand that life on Mars is probably a lot more limited and most likely to be found underground. It could be inhabiting lava tubes, for example—the large winding caves formed by ancient magma flows—where subterranean water is heated by the planet’s core. Researchers are currently working on an insect-like, wall-climbing robot to investigate.

Life could also be proliferating in underground saltwater lakes. Reported in 2018 based on radar data from the orbiting Mars Express, the first suspected lake of this type is around 1.5 kilometers beneath the surface close to the south pole, and at least 20 km across. Magnesium, calcium, and sodium perchlorate salts are thought to act as antifreeze, keeping the water in a liquid—albeit inhospitably briny—state. Comparable lakes in Antarctica are host to plenty of microbial life. Unfortunately, however, it’s tricky to land craft at the southern pole of Mars, owing to the thinner atmosphere and rougher terrain of the region.

Scientists will certainly endeavor to make it happen, though. In the meantime, we can only speculate as to what this life might be like. Perchlorate salts are toxic to most Earth lifeforms, but one notable exception is Dechloromonas aromatica. This ocean-dwelling bacteria breaks down salts using enzymes and converts them into chloride and oxygen to breathe. On Mars, it’s also possible that microbes have evolved to breathe not oxygen but methane—a gas known to seep from the planetary interior.

Of course, Martians may not be microbial in nature. Although the limitations of the planet’s atmosphere and climate are assumed to restrict lifeforms to very simple expressions, they could be more complex than we think.

Either way, the discovery of life on Mars will have ethical implications for colonization. Terraforming, in particular, could wipe out all existing life on the planet—even before we’ve had a chance to meet it. But even the arrival of humans risks contamination. For this reason, the scientific community will probably impose restrictions on where human colonists can go. Areas designated Special Regions under a Planetary Protection Policy will be strictly off-limits—not just for the Martians’ own safety but also to prevent potentially deadly, potentially rapidly multiplying Martian bacteria from hitching a lift on to Earth.

3 Comments

“There may be life on Mars now”

That isn’t a fact but pure speculation. I could say I may have an extra kidney in my body. I could say that my next door neighbour has a dead hooker in his freezer. Doesn’t mean it’s true therefore it isn’t factually correct.

Many of these entries are not facts, just fanciful speculation.

All facts.