Highwaymen lived fast and (usually) died young. But they weren’t just any old bandits. While not all of them gave to the poor, they only ever stole from the rich and thus tended to see their crimes (as a lot of the public did too) as essentially morally righteous—or at least no worse than their victims’.

Last time we did a list on this topic, we went with some quirky examples—namely women and a man called Sam Poo. But as commenters were quick to point out, this left some glaring omissions. The best suggestions are listed below, along with some other big names.

10. Willie Brennan (18th c.-?)

It’s interesting to note how many of the best known highwaymen, bandits, and bushrangers around the world were of Irish descent. Jesse James, Black Bart, Ned Kelly, and others could all trace their roots to the Emerald Isle. Yet we know relatively little about the ones who stayed there.

All we really know about Willie Brennan, for example, is from a ballad about his life. According to the song, he haunted the hills around Limerick and preyed on the rich with his pistols. One of his victims went on to become his accomplice, having been robbed of his money, watch and chain and “robbed [Willie] back again.”

Unfortunately, he was later betrayed by another acquaintance and taken prisoner by the cavalry. Both he and his accomplice were hanged and the ballad ends with his goodbyes—even to his “loving mother, who tore her gray locks and cried, / Saying ‘I wish, Willie Brennan, in your cradle you had died.’”

Another version of the ballad hints at his continued existence: “They hanged Brennan at the crossroads, in chains he hung and died, / But still they say that, in the night, some do see him ride. / They see him with his blunderbuss, all in the midnight chill. / Along, along the King’s highway rides Willie Brennan still!”

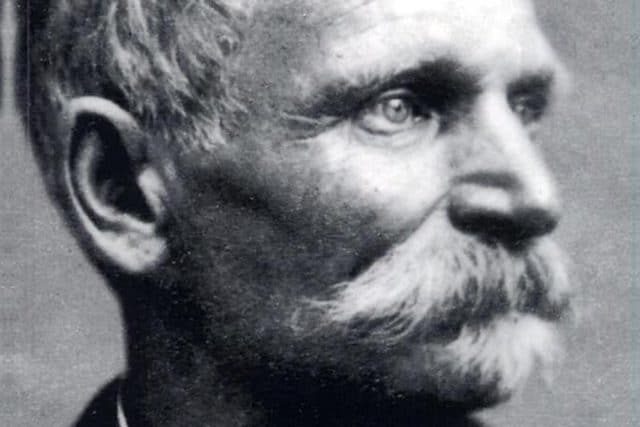

9. John Nevison (1639-1684)

Sometimes called William, sometimes called John (and sometimes Swiftnicks or Tom), Nevison is fondly remembered as the politest highwayman in Britain. Like so many others, he robbed from the rich and gave to the poor, but always in the politest way possible. He didn’t even consider it theft, but rather a “quarterly tribute on all the northern drovers.” In return, he promised to protect them from bandits.

Nowadays, he’s probably best known for his daring evasion of capture in 1676, a story that became so legendary in its own right that other highwaymen often took credit (including Dick Turpin, who wasn’t even born at the time). Having been identified in a pre-dawn hold-up down south, Nevison fled back up north to secure a watertight alibi: gambling on bowls with the Lord Mayor of York—just 15 hours later. Since nobody thought it was possible to ride 227 miles in so short a time, and since the Lord Mayor himself could attest to Nevison’s whereabouts, the well-heeled highwayman was allowed to go free.

In the end, though, following a number of other close shaves, he was betrayed by an innkeeper and arrested while drunkenly asleep in a chair. Tried for highway robbery, as well as the murder of a constable, he was hanged at York in 1684.

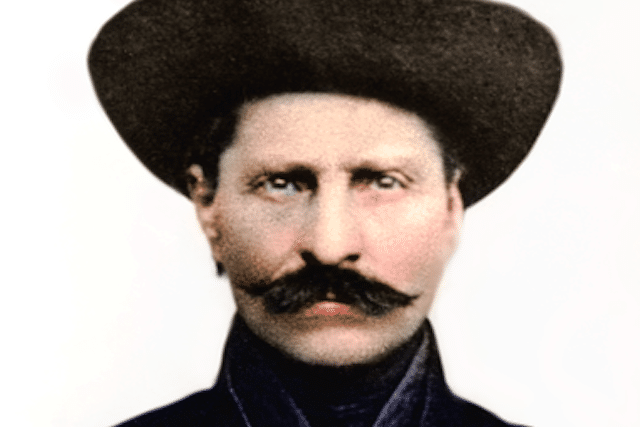

8. Sándor Rózsa (1813-1878)

The Hungarian betyár (or bandit) Sándor Rózsa lived a relatively long life for a highwayman, dying in prison at the age of 65. When he died, newspapers around the world described him as a “robber king” and “celebrated bandit” born into a family of thieves.

Much like Robin Hood, Rózsa was generous to the poor, gallant to women, and had nothing but disdain for the law, frequently attacking police and military even in broad daylight. At the height of his renown, wealthy Hungarians knew better than to travel without a tribute for the bandit.

Even jails couldn’t hold him. The first time he escaped from prison, aged 23, he had help from the outside. But on another occasion, he was freed simply because the skills of a highly trained bandit like him were needed in the revolution of 1848. He was jailed again in 1856, this time betrayed by an accomplice (who Rózsa shot dead in front of the arresting officers); however, his initial death sentence was commuted to life in prison and ultimately to early release. His final stint in prison, from 1868, was also cut short—albeit by his own death from tuberculosis—having already been commuted from the death sentence to life in prison.

7. Gamaliel Ratsey (d.1605)

Gamaliel Ratsey “took to evil courses as a boy,” departing from the genteel world of his father to steal money and horses from the rich. Among other things, he was known for his theatrical zeal, holding up coaches in a grotesque and frightening mask and forcing one victim, an actor, to play out a scene from Hamlet.

But he “accorded with the best traditions of his profession” as a champion to the poor and a reckoning for the wealthy. Rarely did he ply his trade in silence; every hold-up was an opportunity to profess the moral high ground, and he did so with the eloquence of a bard.

“There is no pity to be had of thee,” he once told a lawyer at gunpoint, “thou art worse than I …. You [lawyers] pick every poor man’s pocket with your tricks and quillets, like vultures preying upon your clients’ purses.” When the lawyer protested that his fees were actually quite low—a mere ten shillings as standard—Ratsey softened his approach, but only to make his point clear. Giving 20 shillings back to his victim, a stipend to pay off his driver, the highwayman left him with this: “I would give it all again and a great deal more too, upon condition that lying were as little used in England among lawyers as the eating of swine’s flesh was amongst the Jews.”

6. Charles E. Boles, aka Black Bart (1829-?)

Black Bart gained notoriety in the Old West for robbing the gold-laden coaches of the Wells Fargo Company. He held up his first outside Copperopolis, California, in 1875—dressed in a full-length duster with a sack draped over his head. Waving down the coach with a shotgun, he simply shouted out “throw down the box.” On his third hold-up in 1877, Black Bart left the first of his poems at the scene—a habit for which he became known as the “Stage-Robber Poet” in the press. “I’ve labored long and hard for bread,” it read, “for honor and for riches, but on my corns too long you’ve tred, you fine haire sons of bitches.”

Infuriatingly for detectives, he left no other clues behind—no hoofprints, no discernible pattern to his crimes, and he never even fired his gun. Detective James Hume had no choice but to pursue him blindly through the wilds of northern California, measuring distances and talking to farmers.

Eventually, however, one of Black Bart’s hold-ups went awry. Despite getting away with $4,800 in gold, he left a damning clue: a shotgun shell wrapped in his own laundry-marked handkerchief, allowing Hume to track him down via his laundryman. And when he did, Hume was surprised to find a decent, middle-aged man behind the crimes—a Civil War veteran seeking his fortune out west. Given that a lot of his loot was saved up and could be returned to Wells Fargo with ease, and given that his shotgun had never been used (or even loaded, apparently), Black Bart spent just four years at San Quentin.

When he got out, he announced to the press that his days as an outlaw were over. As to whether he’d keep writing poetry, as one reporter wanted to know, he said: “Young man, didn’t you just hear me say I will commit no more crimes?” His actual fate remains unknown, but he may have returned to his family.

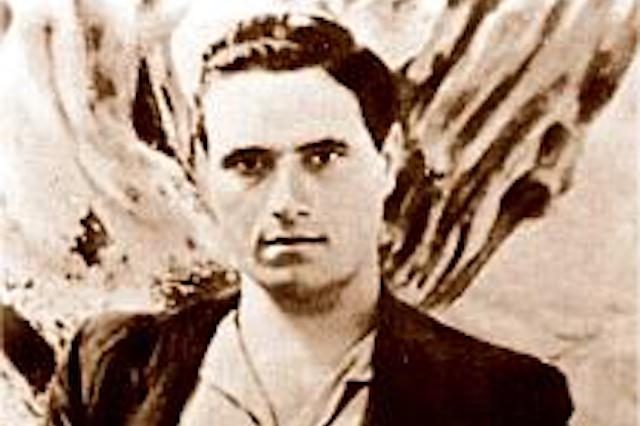

5. Salvatore Giuliano (1922-1950)

Described by historian Eric Hobsbawm as the last of the “people’s bandits,” Salvatore Giuliano’s exploits had much of the world enthralled.

His first encounter with the police was as a young man transporting black market grain to peasants in the Sicilian countryside. Back then, rural communities were forced to rely on illegal supplies and Giuliano was doing them a service. But the armed police saw things differently. Although Giuliano managed to escape, he took a bullet while dashing for the hills and accidentally left his ID behind. With this in hand, the police had no need to pursue him; he’d either die of his wound, they supposed, or be arrested soon enough. Little did they know what a nuisance he’d be to the state, and what a hero to many of its people.

Giuliano spent the next seven years on the run, retreating into the Sagana mountains and gathering bandits around him. He also had the support of the Sicilian Independence Movement and sought the backing of America too, twice asking President Truman to annex Sicily as the 49th state.

To support themselves, Giuliano and his men kidnapped various government officials and held them to hefty ransoms, though always with the utmost respect—housing them, feeding them, and even providing entertainment. Approval from the public was absolutely essential, and for the most part entirely forthcoming. It was only when Giuliano’s gang botched a kidnapping attempt in 1947 and ended up killing civilians that things took a bit of a downturn.

Giuliano was gunned down three years later at the age of 27. Although he appears to have been shot by police, his death is still shrouded in mystery. Some think he survived and fled to America, while others blame the mafia, or his cousin, for the hit. Nevertheless, his reputation was sturdy enough to outlive him. Barely a decade later, he got his own blockbuster biopic.

4. Claude Duval (1643-1670)

A Frenchman by birth, Claude Duval traveled to Britain as a page to a “person of quality.” He’d made friends with highly placed exiles in Paris during the English Civil War and, in spite of his humble origins, developed the manners and bearing of an English noble gent. He wore fashionable clothes, knew how to woo ladies (of practically any social class), and never used violence against his victims.

He was known as the Gallant Highwayman, “an eternal feather in the cap of highway gentility.” He also liked playing the flute. When a noblewoman whose coach he’d stopped took out hers to start playing (apparently to calm herself down), Duval enthusiastically joined in. Complimenting her on her skill, he even got her to join him for a dance. It was almost as an afterthought, a mere formality of the trade, that he made off with £400—payment, he told her gobsmacked husband, for the exquisitely impromptu show.

He was eventually caught and sentenced to death, arrested while drunk at a tavern. Unfortunately, despite numerous pleas from his mostly female admirers—and even King Charles II—the judge refused to grant a reprieve. In fact, he was so adamantly (and presumably jealously) opposed to the young man’s continued existence that he threatened to resign if he lived.

Duval was only 27 when he hanged at the Tyburn gallows. But his funeral was lavish and well attended, and his epitaph appropriately poetic. It finished with the lines: “Old Tyburn’s glory; England’s illustrious Thief, / Du Vall, the ladies’ joy; Du Vall, the ladies’ grief.”

3. James Hind (c.1616-1652)

Claude Duval wasn’t the only highwayman with friends in high places. The well educated Captain Hind actually fought for the Royalist cause during the English Civil War. And, according to some, he may have helped Charles II escape. Even as an outlaw, he remained fiercely loyal to the Crown.

Indeed one of his earliest marks was Oliver Cromwell himself, Lord Protector of the new British republic and a signatory to the death warrant of Charles I. But his coach was heavily under guard, accompanied by a military escort, and Hind barely escaped with his life. His mentor Thomas Allen was not so lucky.

Undeterred, Hind went on to rob several other high-profile republicans. The preacher Hugh Peter, for example, one of the first to call for Charles I’s execution, was hunted down and humiliated for his crime. Dismissing his appeals to scripture and calling him a “detestable hypocrite,” Hind not only took his gold but his cloak and his coat as well. The following Sunday, Peter gave a sermon on the subject of theft and quoted Canticles 5:3: “I have put off my coat, how shall I put it on?” But he wasn’t to get the last word; the congregation wasn’t sympathetic. When someone shouted out “I believe there is nobody here can tell you, unless Captain Hind was here,” the whole church exploded in laughter.

Next up was John Bradshaw, who as judge had given Charles I the death sentence. Hind overtook his coach in the black of night and loomed over the man inside, saying: “I fear neither you nor any king-killing son of a whore alive. I have now as much power over you as you lately had over the King, and I should do God and my country good service if I made the same use of it.” But he didn’t. Instead, he took Bradshaw’s money and killed all his horses, leaving him stranded and at the mercy of other bandits.

Hind was finally arrested after the Battle of Worcester and hastily locked away. Although by rights he should have been freed under Cromwell’s own 1652 Act of General Pardon and Oblivion—an amnesty for defeated Royalists—his was no ordinary case. Charged with high treason, he was hanged, drawn, and quartered so a chunk of his corpse could be spiked over each of the gates to the city. Only his head received a proper burial, one week after his death; the rest was left out to rot.

2. Dick Turpin (1705-1739)

Falling in with the notorious Gregory Gang of Essex, near London, Dick Turpin got his start stealing cattle. But he wasn’t merely a poacher. In 1735 he was involved in the burglary of an Edgware farmhouse where the gang stripped and tortured a 70-year-old farmer by pouring scalding hot water on his head and forcing him to sit on a fire. They also tied up his maidservants and stood by as their leader raped one.

When the gang fell apart in 1735, Turpin tried his hand as a highwayman. He went on to become one of the best known bandits of his day, making off with hundreds of pounds’ worth of loot. But he didn’t stick it out for long. After killing a man to avoid capture in 1737, he fled up north, changed his name to John Palmer, and supported himself stealing horses.

Then, for whatever reason, he decided to shoot a cockerel in the street and wave the gun at his landlord, threatening to shoot him too. For this, he was jailed at York Castle; however, since he hadn’t been identified as Dick Turpin, all was not yet lost. Not until he wrote to his brother-in-law for help, and Turpin’s old schoolmaster recognized his handwriting at the post office.

For his crimes as an outlaw, Turpin was sentenced to hang at the age of 33. But fate had another cruel twist in store: it was a fellow highwayman—one Thomas Hadfield—who served as his executioner at the gallows. In return, Hadfield, himself a condemned man, was pardoned and allowed to go free.

1. Ned Kelly (1854-1880)

Settler families like Ned Kelly’s had a hard time in colonial Australia. Despite having been assigned land by the Crown before they arrived, they often found squatters settled there first—and the squatters weren’t willing to share. Not only were they better connected with more money and resources than most of the impoverished settlers, squatters also had the backing of police. Hence the Kellys were on the wrong side of the “law” by default, and were forced to steal livestock to survive.

Ned himself was in and out of prison from the age of 14, often on trumped-up charges. But the police soon hatched a plan to lock him up for good, along with his brother Dan, for allegedly shooting a trooper. They didn’t need evidence; the judge and jury were in league with the police. In any case, when they finally tracked the Kelly brothers down in October 1878 (having jailed their mother for aiding and abetting), they had only to provoke them to shoot in self-defense. The Kellys escaped again, but the police got plenty of evidence.

The Kelly gang spent the next two years as bushrangers, robbing the rich to survive as well as to make their point. On one hold-up, Ned left behind a manifesto, his so-called “Jerilderie letter”—56 handwritten pages about his background and the cruelties of the state. He also insisted that he “never interfered with any person unless they deserved it,” by which he meant “any person aiding or harboring or assisting the police in any way whatever.” As far as he was concerned, they were all “big ugly fat necked wombat headed big bellied magpie legged narrow hipped splawfooted sons of Irish bailiffs or English landlords.”

As the reward for their capture increased, Ned and his gang holed up at the Glenrowan Inn in June 1880. By now, the police just wanted them dead and opened fire on the hotel from the outside. Several innocent bystanders lost their lives, along with most of the gang. Although Ned survived, retreating into the bush as the police set the hotel ablaze, he returned before dawn in his makeshift metal armor for one final, doomed shootout with the law.

Despite his newfound popularity with the public, he was sentenced to hang at the age of 25, uttering the famous last words “such is life” (or possibly just “oh well I suppose it has come to this.”) It wasn’t for another 130 years that he’d receive a proper burial, though. Against the wishes of his enemies’ descendants, Ned Kelly’s remains were forensically identified and disinterred from the mass grave they’d been flung in and relocated to his homeland of Greta. The grave has been left unmarked, however, to protect it from grudge-holding vandals.