In recent months, new research has come out suggesting that our historical love affair with Mars as a potential second home isn’t going to work out. From technological challenges related to radiation, gravity, water production, and human physiological and psychological problems that might arise due to prolonged isolation, it very much looks like Mars isn’t a good candidate for our second home.

But what about Venus?

Sure, its surface is the very definition of hell, with an average temperature of 471 degrees Celsius. But new engineering proposals, as well as new research on the Venusian atmosphere, may prove that not only is Venus a great choice for our home away from home, but that it might be the only choice.

Here are 10 reasons why a Venusian settlement is a good idea.

10. Gravity

Most of the other planets and moons in the Solar System are small, with only a fraction of the gravity offered by our home. And while dreamers will speak of a time when humanity might create great habitat rings around Jupiter and Neptune to harness their gravity. Technology of that level is hundreds, if not thousands of years away, and there’s only one planet in the Solar System with gravity nearly identical to Earth: Venus.

Humans evolved within Earth’s gravitational field, and new research into the effects of space travel shows that prolonged exposure to zero-g environments are harmful to the human musculature system. Depriving the human muscle system of gravity leads to atrophy in less than nine days without intervention. Our skeletal system is evolved to constantly fight against the pull of Earth’s gravity, and without it, space-flight-induced osteoporosis can occur. The organs in our inner ear are also adversely affected by a lack of gravity.

Even astronauts who exercise regularly to prevent these issues on the International Space Station end up needing months of physical therapy once they get back to Earth.

But, good news everyone, Venus has a gravitational field 91% as strong as Earth, and most scientists agree that you wouldn’t feel much of a difference trying to move. You might be able to leap a bit further, but beyond that, the side effects would be minimal.

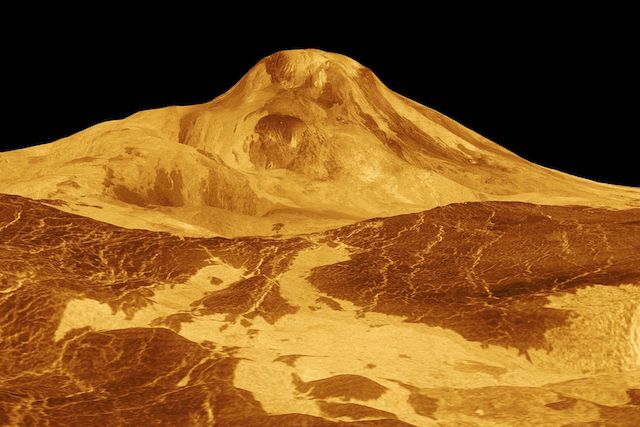

9. The Surface is Relatively Calm

If we were ever able to deal with the searing temperatures that the Venusian surface offers, its flat, smooth plains may be the perfect place to create a base for ourselves.

While wind speeds in the upper atmosphere can reach an excess of 400 kilometers per hour, the surface experiences a benign 3 kilometers per hour wind speed.

Because of its retrograde rotation, the sun would appear as a hazy yellow light as it rises in the west. A year and a day on Venus take 243 and 117 Earth days respectively, and at night, settlers would experience a pitch-black environment.

8. NASA’s Brilliant Cloud City Plan

Scratch everything we just said about a Venusian surface base. We don’t have the technology to make that a reality yet, and there’s a better alternative.

About 50 kilometers above the Venusian surface is a place where the immense pressure evens out to 1 bar, the gravity is just about right, and the protection from harmful cosmic and solar rays is just about the same as it would be on Earth. And while the temperature stays at a blistering 60 degrees Celsius, we have technology that would be able to handle those temperatures.

And because air is lighter than carbon dioxide, you could fill a balloon with atmosphere identical to the Earths and it would fly into the atmosphere the way helium-filled balloons do on old terra firma.

A 1-kilometer balloon has the potential power to lift two Empire State Buildings into the Venusian atmosphere, and larger balloons would fair even better.

If we constructed a large enough balloon, hypothetically, it could support all of the materials and equipment that settlers need to survive on Venus.

And, if the outer wall of our balloon city ever ripped? Well, it’s not going to pop the way a balloon does on Earth. The outside and inside pressures are equal, so you’re not going to get a violent explosion, and the larger the city is, the better. It would be like opening a window here on Earth. The outside air would slowly mix with the air of the city, and vice versa, but there would be plenty of time to fix the problem.

7. Acid Ain’t No Problem

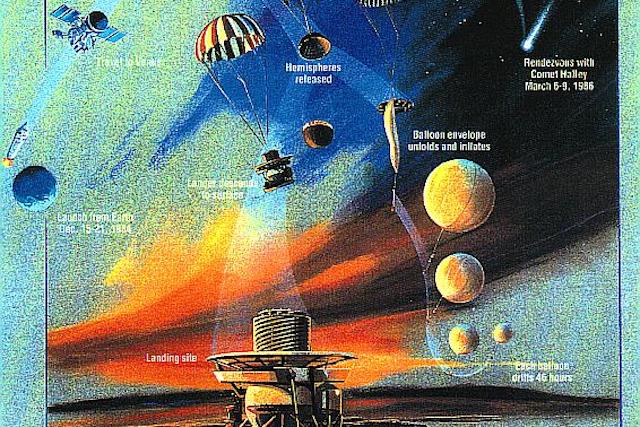

Protecting our hypothetical Venusian settlement from roaming clouds of acid would be an absolute must, and fortunately, we have the technology to do so. The Soviet Vega mission in 1984 actually floated in this region (50 kilometers above the surface) for two whole days, and the balloons which held Vega aloft for that time were coated with Teflon. Teflon, it turns out, is highly resistant to the types of acid clouds in Venus’ atmosphere.

Teflon was discovered completely by accident, and scientists searched high and low for a chemical which could harm the stuff, even going so far as to test a substance nicknamed “the Gas of Lucifer” (which has blown up plenty of scientists messing with its components) and not one of those chemicals was capable of eating through good old Teflon. So, it would be more than up to the task of defending our settlers from acid clouds.

6. Acid and Carbon Dioxide as a Resource

Even if we could get cloud cities set up on Venus, there still are a lot of logistical problems that need to be handled. How do we produce air, water, and power? Well, the Venusian atmosphere already has much of what we need. CO2 can be split into oxygen and carbon, and sulfuric acid could be split into water, oxygen, and sulfur.

We’d be able to go about this with a method already used to generate breathable oxygen for astronauts aboard the International Space Station: Electrolysis!

5. It’s Close to Earth

Probably one of the biggest reasons why Venus is more ideal than Mars or any other planet in the Solar System is that it’s the closest one to the Earth. The challenges inherent in attempting to transport cargo are nearly insurmountable without a more efficient fuel source, but Venus is only 261 million kilometers away from us.

A resupply effort would take roughly three to four months depending on where Venus is in relation to the Earth’s orbit. We’re talking about 97 days. A trip to Mars could take up to 6 months, and that’s if we’re lucky.

At 97 days, the cost to resupply a Venusian colony would be significantly lower than for Mars or any of Jupiter or Saturn’s moons.

4. Communication

Venus being the closest planet to the Earth means that communication times would be significantly better in favorable conditions than on Mars. When Venus is closest to the Earth, transmissions to and from would only take between two and five minutes, and if Venus were just a little further out, it would still only take about 8 minutes to receive a message.

Though, on the downside, if Venus was on the other side of the sun, then those same communications would take about fifteen minutes.

3. There May Yet Be Life on Venus

Venus has long been ruled out as a planet that could ever support life. But like the reasons why Venus continually gets passed up by the folks at NASA for potential missions, it’s possible that we’re simply not thinking creatively enough about the possible places where life could evolve there. And if the sweet spot for human life is 50 kilometers above the Venusian surface, then couldn’t its atmosphere support some sort of airborne life?

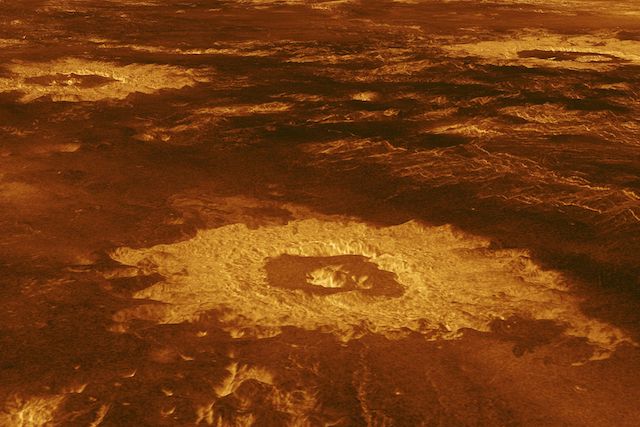

It’s thought that billions of years ago, Venus had oceans of liquid water and plate tectonics, just like the Earth. If this was indeed the case, then it’s possible that our so-called sister planet once evolved life. Some even suggest that Venus could have been much like the Earth for a large majority of the Solar System’s history.

Today, that’s not the case. But in the last couple of decades, we’ve discovered life in places on the Earth we never before thought possible. Extremophiles near oceanic vents, and a deep biomass of simple lifeforms stretching nine kilometers beneath the surface of the Earth. Who’s to say that there isn’t still life thriving in Venus’ atmosphere? And if there was life, could settlers living in said atmosphere harness those organisms for their own purposes?

Some scientists think so.

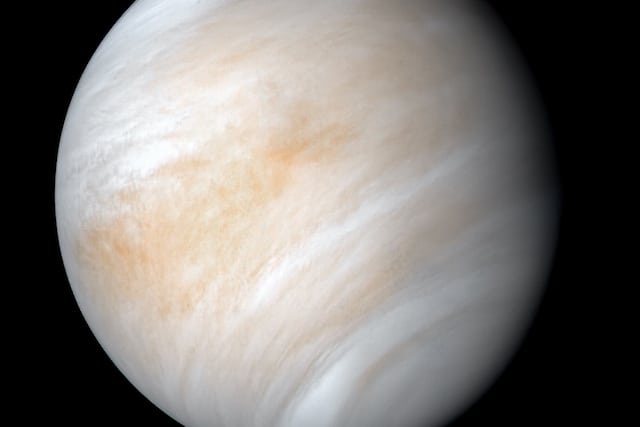

Interestingly enough, Venus’ upper atmosphere holds a mysterious compound that absorbs ultraviolet radiation, and no one knows what this stuff is. Some researchers have suggested that this compound could be biological in origin, similar in composition to sunblock.

Funnily enough, just a couple days ago on September 14 a scientific paper was released detailing the observations of a gas known as phosphine in the Venusian atmosphere. The interesting thing about this gas is that it’s only been seen as a byproduct of life, making it nearly certain that the phosphine on Venus is produced by some kind of life-form in the planet’s thick atmosphere.

2. Sky Balloon Vehicles and No Pressurization Needed

Once there, exploring Venus would be as easy as hopping on a vehicle made from Teflon coated balloons and sailing the clouds. Settlers leaving the safety of their sky city wouldn’t need a pressurized suit, either, because of reasons already mentioned in earlier entries.

NASA is even proposing using floating probes (which use balloons) to study the Venusian surface, traveling safely on gale-force winds. These balloons could be equipped with extremely sensitive seismometers to detect seismic activity below.

Most scientists agree that before we can attempt to settle Venus, we would need to know more about it. Of the four inner planets of our Solar System, we know the least about Venus, and testing these balloons in the upper atmosphere could go a long way toward paving the way for a potential settlement.

1. It May be Easier to Terraform

Venus is home to a massive runaway greenhouse effect, thanks to its thick, CO2 rich atmosphere. It’s the hottest planet in the Solar System, even though it’s only the second one from the sun. Many methods have been proposed for terraforming Venus, both in science fiction and by real scientists. Carl Sagan suggested using a type of genetically engineered bacteria to transform the carbon and split it into organic molecules (similar to what electrolysis can do), but this was shot down as impractical once the roaming clouds of sulfuric acid were discovered.

In 1991 British scientist Paul Birch suggested using hydrogen to bombard Venus’ atmosphere, producing graphite and water. This would require so much hydrogen that it would need to be harvested from one of the gas giants in our Solar System, and we’re not quite there technologically speaking.

There are other proposals as well, but perhaps the most practical one, comes in the form of a solar shield, or a solar sail intended to block out a portion of the sun’s light from hitting the Venusian atmosphere. Similar proposals have been made to help reduce the effects of climate change here on Earth.

If placed in Venus’ L1 Lagrange point, it would help to gradually cool the atmosphere. Such a shade would also block a portion of the solar wind. The result of this would lead to the freezing of CO2 in the upper atmosphere. Dry ice would then rain down onto the surface of the planet.

An alternative idea is to place solar reflectors in the atmosphere—say, on top of several very large floating balloon cities? Even if said reflectors weren’t built on top of a hypothetical balloon city, the Venusian atmosphere is thick enough that they could be constructed to float on the surface of the clouds, needing little to no human maintenance.

These methods wouldn’t cool Venus immediately, we’re talking about timescales on the level of generations to accomplish. But settlers already on Venus could help kickstart that process, and eventually, make Venus a world worth calling Earth’s twin.