From swashbuckling buccaneers, shrewd British Royal Navy officers, bitter salt pork, to climactic battles and wars for succession and control of the Caribbean, the Age of Sail is full of historically significant events, and so, so much scurvy.

It lasted from the year 1571 to 1862 and is sometimes called the Age of Scurvy thanks to the poor living conditions and menus of most sailing vessels.

Here are 10 amazing facts about the Age of Sail.

10. Food in the Age of Sail

The famous quote from Samuel Pepys, “Englishmen, and more especially seamen, love their bellies above anything else,” effectively illustrates the attitude most sailors had toward food on their voyages during the Age of Sail. If provisions appeared to or were rumored to be short on a voyage or vessel, this could turn potential recruits away from the Navy.

The most common food stores aboard sailing ships was a less than healthy assortment of ship’s biscuits, salt pork, and of course, rum (and lots of it). Though there were other items available to sailors, there’s a reason why these became the cliché go-to menu for people crafting stories around the Age of Sail.

Though, the rations available to sailors could differ greatly depending on whether ships were coming from the Caribbean or European waters. The best records of these food stores come from the British Royal Navy. In 1677, Samuel Pepys, the Secretary of the Admiralty copied a contract made with local food and alcohol providers, detailing the weekly rations of a member of the British Royal Navy. These rations included 1 pound of biscuits, a gallon of beer, 4 pounds of beef, 2 pounds of salted pork, 3/8s of a 24 inch cod, 2 pints of peas, 6 ounces of butter, and 8 to 12 ounces of cheese.

Given this list, it’s no wonder why so many succumbed to scurvy.

9. Harsh Punishments

During the Age of Sail, a seaman’s life was particularly difficult, and ship’s officers kept rigid rules in place to keep their men orderly and reduce the risk of a mutiny.

Violators of these rules could face all kinds of cruel punishments. One of the most famous acts of barbarism is when sailors would tar and feather rule-breakers, an act of humiliation which saw sailors stripped of their clothes and covered in wood tar (which was sometimes hot) and then coated with feathers.

Less egregious offenders would be forced to climb the mast and stay there, bearing the cold winds of the sea. Though this could be isolating, most sailors saw this as a great opportunity to get some reading done. Others might be smacked over the back with a wooden cane, a punishment that was often reserved for minors. Offenders received 6 to 12 strokes with a thick 3 and ½ foot cane. If a boy committed a more serious offense, he might be subjected to a birching, where an officer would hit an offender 12 to 24 times with a bundle of birch sticks.

Adult offenders might be flogged with the infamous “cat o’ nine-tails” or with the end of a heavy rope. This would be done on a sailor’s bare back, and the wounds left in the wake of the rope or a cat o’ nine-tails were serious enough that there was a risk of infection. To prevent infection, officers would rub salt into the offender’s wounds after the event.

One of the worst punishments involved throwing sailors overboard so that they would be dragged underneath the ship’s bottom. This was called “keelhauling” and directly endangered the sailor’s life and was generally much rarer than flogging. Hangings were also a common punishment and though popular culture would have you believe that pirates practiced the cliché act of forcing their prisoners to “walk the plank” there is no historical evidence that this was ever actually done.

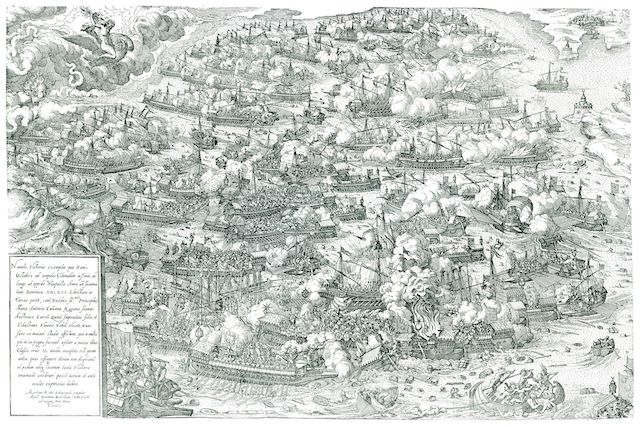

8. The Battle of Lepanto

The Battle of Lepanto was the last major naval battle to feature boats with rowing mechanisms and it’s thought to be one of the greatest conflicts in the era before modern history.

After the rise of Sultan Selim II in 1566, the Ottoman Empire had its sights set on removing Christian settlements from Africa and claiming the territory for its own. Some historians agree that if the Holy Fleet had not been able to drive the Ottoman forces back during this battle, that much of Europe would have fallen to Muslim forces. Perhaps, today instead of communion, Europeans would be declaring the truth of Mohamed instead.

Each side used ships known as “galleys,” flat ships that were powered primarily by rowing, though they did feature sails that could be used if the wind was favorable. These types of ships were commonly used for trade, warfare, and piracy. As warships, they typically featured rams, catapults, and cannons as their primary weapons.

On the morning of October 7, the Turks and the Holy Fleet engaged in a vicious battle which quickly descended into bloody hand to hand combat. In the end, the Holy Fleet was victorious, and a large majority of Europe rejoiced at the good news.

7. Press Gangs

The conditions aboard ships in the British Royal Navy were less than favorable for a potential recruit, and life among their ranks was anything but safe, so it should come as no surprise that recruitment through peaceful means was difficult. To convince seafaring men in the merchant fleet to join the war effort, officers would round up 10 to 12 men and gang up on those reluctant to join the navy. The act of impressing was even endorsed by parliament at times.

Those victim to a beating at the hands of a press gang were often knocked unconscious and it was common for violent fights to break out as a result of the threats levied at potential “volunteers.”

Men who were apprentices or officials from foreign governments were seen as off-limits, and the Royal Navy did not officially take on sailors outside the age range of 18 to 55, but the rules were often broken so that those in a press gang could earn their reward since they were paid by the head.

6. The Battle of Hampton Roads

In March 1862, the Age of Sail came crashing to an end, as the confederate owned CSS Virginia demolished the wooden fleet owned by the Union. The CSS Virginia was the first steam-powered vessel constructed by the Confederacy, and it famously sank the USS Cumberland and set the USS Congress on fire. The CSS Virginia was built as an answer to the Union’s blockade of Southern ports, which included Norfolk, Virginia.

It wasn’t until the Union debuted their own ironclad ship that the tides of battle turned. The USS Monitor and the CSS Virginia battled to a standstill, neither side being able to seriously damage the other.

Originally, the CSS Virginia was a 40-gun frigate ship known as the USS Merrimack. The Merrimack first launched in 1855 and was the flagship of the Pacific fleet until 1860, when it was decommissioned and stored at the Gosport Navy Yard in Norfolk, Virginia, where it remained until the outbreak of the Civil War. The Merrimack was sunk by Union sailors, and six weeks later, the Confederacy salvaged it and began rebuilding and retrofitting it into the steam-powered vessel that would debut at the Battle of Hampton Roads.

5. The Free Sailing Buccaneers

Seen by the Spanish as mere pirates, buccaneers are seen as semi-lawful sailors by today’s historians, who famously harassed Spanish ships and ports in the Caribbean in the 17th century. The Spanish considered the Caribbean (and all of its gold and silver) to be the exclusive property of Spain. At first, the buccaneers were just ordinary French and English settlers who lived on Hispaniola and other Caribbean islands.

They got their name from the word boucan, and in fact most of the early buccaneers were hunters, who used to smoke the meat of wild animals. Eventually, they were driven out of Hispaniola and this created in them a deep, seething hatred for Spain. Those who ended up in Tortuga forged a brotherhood known as the Brethren of the Coast, and by the 1630s, they were no longer hunters, but men of the sea. Their attire consisted mostly of pilfered goods obtained through the plundering of Spanish ships.

Initially, the buccaneer’s boat of choice was the flyboat or pinnaces, used to sneak up on Spanish vessels. Using the cover of darkness, buccaneers would jam the ship’s rudder up to prevent it from escaping and would then board it before an alarm could be raised. They were known for their expert marksmanship and would kill helmsmen and officers.

Thanks to a combination of these buccaneers and new French and English colonies in that part of the New World, Spain’s control over the Caribbean would end in 1898.

4. The Pirate Round

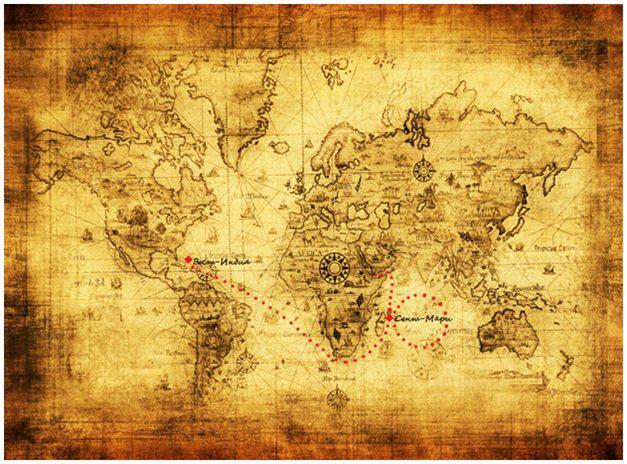

The Pirate Round was a route taken by less than lawful mariners, often looking to pilfer Spanish ships, in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. “Rounders” as these pirates were often called, started their journeys in the New World, New York, and even Nassau, and would travel the winds and sea currents to the Portuguese island of Madeira to re-supply and clean the bottoms of their ships.

Once ready, they would sail around the Horn of Africa, around the tip of the African continent (known as the Cape of Good Hope), and up the eastern coast to the Mozambique Straight, leading them right up to the northeast of Madagascar.

The island of Madagascar made for a perfect pirate base, as it was outside the influence of European laws or politics. The base was created by a pirate named Adam Baldridge in 1687, who subdued the native population and took tribute from them, and would later go on to create a trading company which would supply pirates with clothing, gunpowder, ammunition, and of course, rum.

England would finally start to crack down on piracy in the year 1700, but they would do so by hiring unreliable privateers to do the work. Men like Captain Kidd would start their careers out as pirate hunters, but greed would win out once they saw the riches that could be had if they turned to piracy, and many did just that.

The Round would see a decline after the destruction of Adam Baldridge’s base on Madagascar, until about 1719, when there would be a brief renaissance thanks to names like Edward England, John Taylor, Oliver La Buse, and Christopher Condent. Many of these men refused to accept pardons for their past deeds and were eventually forced out of Madagascar by the East India Company.

By 1721, the Pirate Round’s life as a hotbed for brigands and plunderers would end.

3. The War for Spanish Succession

The death of childless (and therefore heirless) Charles II came with it a dispute of who should succeed him. To keep things calm between the three claimants in 1698, England, the Dutch Republic, and France signed the First Treaty of Partition, which declared that succession go to Prince Joseph Ferdinand, son of the elector of Bavaria. In 1699, however, Ferdinand would die, forcing a second treaty to be drafted, granting Spain, the Spanish Netherlands, and colonies to Archduke Charles, the second son of the Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I. Naples, Sicily, and other Spanish territories in Italy would be given to France.

Leopold refused to sign the treaty and demanded that Charles receive all of the Spanish territories. But Charles II believed that only the House of Bourbon had the power to keep Spain intact, and in 1700 bequeathed them to Philip, Duc Ad’Anjou, who was the grandson of Louise the XIV of France. However, he would die on November first, and Louise the XIV would declare his grandson king of Spain on November 24.

Philip V would invade the Netherlands in 1701, marking the start of the war. During the war, it was common for privateers to be hired on contracts of war. But, when the war ended in 1714, it would leave many of these men (and their crews) out of work.

Those men would turn to piracy, starting the last era in what’s considered “the Golden Age of Piracy.”

2. The Final Era of Piracy

The ending of the War for Spanish Succession saw many privateers out of work, and because of this, many of them turned to piracy. These privateers turned pirates ravaged the Caribbean (which still had plenty of buccaneers sailing its waters), the Indian Ocean, and the Red sea.

By 1717 Blackbeard, Hornigold, and the rest of the pirates originating in Nassau ruled the Caribbean, but in that same year, King George I issued the “Proclamation of Suppressing of Pirates,” also known as the King’s Pardon. If a pirate surrendered themselves by September 5th, 1718 to a governor of one of the colonies, they would be granted clemency. Hundreds of sailors who thought they would never be free to return to civilization were suddenly free to retire from their lives as criminals.

While many pirates accepted the King’s Pardon, men like Blackbeard and Charles Vane fought to keep their hold on the island.

Piracy as a whole is generally thought to have ended by 1730, thanks mostly to an increase in military presence in waters favored by pirates.

1. The Age of Scurvy

Scurvy managed to kill more than 2 million sailors between the time of Columbus’s transatlantic voyage and the debut of the CSS Virginia in 1862. The disease was so pervasive, that shipowners assumed a 50% death rate for any major voyage undertaken.

Today, we know that scurvy is a simple problem, solved by consuming plenty of Vitamin-C, but back then, it was seen as a problem that could alter the destiny of nations. Sailors could meet all sorts of terrible fates at sea, but none was feared more than getting scurvy. The first symptom was a lethargy so great that it practically crippled most sailors and made many ship captains believe that laziness was the primary cause of the disease. Slowly, the gums would become spongy, the teeth would loosen, and internal hemorrhaging would make splotches appear on the skin of sailors.

Because Vitamin-C functions to scavenge free radicals in the body, which (if left unchecked) can block synapses in the brain, its absence would cause serotonin and dopamine levels to plummet, making sailors afflicted with scurvy experience terrible hallucinations. A cure for the disease would not come for centuries, but sailors superstitiously thought that the smell of earth or being on dry land would help them heal from the disease. Sailors went so far as to pour dirt over those suffering from it, hoping that this would cure them.

Scurvy would continue to plague voyages until 1795 when Sir Gilbert Blane organized the distribution of citrus fruit to seamen.