During its existence from 1922 to 1991, the Soviet Union remained a land of contradictions. It maintained a shroud of secrecy over its operations and people, other than when it crowed loudly of its accomplishments, signifying the superiority of the communist system over the decadent capitalists of the west. The Soviet government, under a succession of leaders, went to great lengths to compete with and surpass the Western powers, in the areas of technology, defense, agriculture, scientific research, education, and the arts. Some of their schemes led to technological firsts, such as Sputnik. Others led to disaster. Still others went nowhere.

Their penchant for secrecy led to their failures often being concealed, but after the collapse of the Soviet government the West gained access to records which documented them. It also learned of other plans, never implemented, that with hindsight seem to be, shall we say, less than well-considered. Here are ten schemes considered or implemented by the leaders of the Soviet Union during that nation’s period of dominating international affairs across the globe.

10. The Tsar Bomba

In the 1950s, despite having successfully detonated a thermonuclear bomb, the Soviets still lagged behind the United States in nuclear weapons. They were behind in the number of weapons stockpiled, and lacked a reliable means of delivering such weapons to targets in North America. So, accepting the premise that bigger is better, they developed the Tsar Bomba, the largest and most powerful nuclear bomb yet built. How that addressed the issue of delivery to the target remains unknown. But the Tsar Bomba (King of Bombs, loosely translated) made a bigger bang than any other, proving to the west the superior military might of the Soviet Union.

Although the bomb test took place in a secured area, the United States Air Force had a KC 135 sensor-equipped aircraft near enough to monitor the detonation. In fact, it was close enough to have the paint seared from the heat of the blast. The bomb worked, with a yield of over 50 megatons, more than 1,500 times the yield of the Hiroshima bomb in 1945. A seismic wave from the explosion made three circumnavigations of the globe before sensors ceased detecting it. Then, having demonstrated that if bigger is better they had the best, the Soviets largely abandoned the project. They then concentrated on ways to deliver smaller bombs, including development of missiles and long-range aircraft.

9. They thought they could keep Chernobyl under wraps

The nuclear disaster which occurred at Chernobyl, near Pripyat in Ukraine on April 26, 1986, remains the worst in history. Ironically it occurred during a safety test at the plant. A series of human errors and failed equipment led to an uncontrolled nuclear chain reaction, an open-air nuclear core fire, and the release of huge amounts of radioactive steam and other gases into the atmosphere. One of the earliest reactions of the Soviet government was to deny the event took place. It was the Swedes who first detected the released radiation and officially asked the Soviet Union whether an accident had occurred. The Soviets denied it. Later, as the evidence of the disaster became overwhelming, the Soviet’s admitted that there had been a minor accident, but everything was under control.

The announcement of the accident to the Soviet public was similarly cavalier, stressing that it was minor, and that there was little call for alarm. It then immediately shifted to lengthy discussions of the American accident at Three Mile Island and other nuclear power incidents in the United States. The reporting slight-of-hand, a common feature of the Soviets, continued throughout the aftermath of the disaster, despite the evidence of its harm to people and the environment. Officially the Soviet Government never admitted the magnitude of the Chernobyl disaster, but the evidence of its coverup became plain to see when the government collapsed five years later.

8. The Soviets studied telepathy as a means of communicating with submarines

Most western mainstream scientists and researchers regard mental telepathy and its counterpart, telekinesis, as pseudoscience. Officially, the Soviets did not. Soviet research into telepathy dated back to the 1920s. They foresaw its use in a wide variety of applications, including secret communications over long distances, with no possibility of covert interception. How long of a distance? The Soviets studied using telepathy to communicate with submarines submerged at sea, and telekinesis to disrupt the guidance systems of enemy missiles and aircraft.

They also studied the use of telepathy and precognition in space, for communication and to foresee and avoid accidents. Soviet planning centered around the study of “bioplasma”, believed by some to be an energy field emitted by all living things. Through its use, properly trained individuals could communicate, or manipulate objects, or see into the future. The American CIA, aware of the Soviet interest in the paranormal, adopted its own program of the study of psychic powers as weapons. It was lampooned in the 2009 film, The Men Who Stare at Goats.

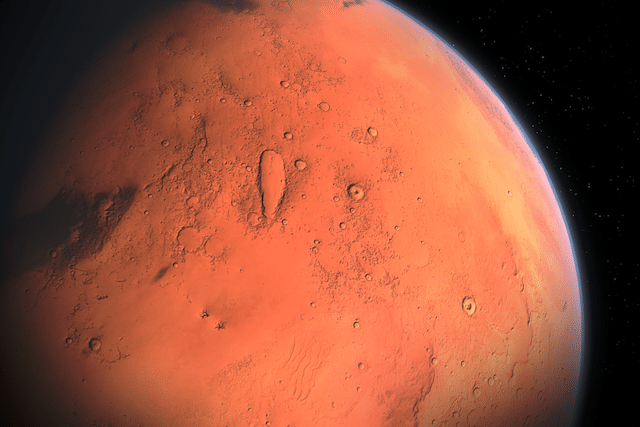

7. Missions to Mars planned for the 1970s

The Soviets were first in space with Sputnik in 1957, the first to launch an animal into space in 1959 (Laika, a dog), and the first to launch a human into space with Yuri Gagarin in 1961. There is evidence though, that at least one cosmonaut was launched prior to Gagarin, kept secret because an accident during the mission proved fatal. At any rate, when they failed to beat the Americans to the moon it proved an international humiliation. That the Americans were winning the race to the moon was evident by the mid-1960s. So, the Soviets decided to develop a mission to Mars, to take place in the early 1970s. Actually, they envisioned several different missions, which included launching nuclear reactors into space.

One such mission, which went deep into the planning stages and included the building of mock-ups of the equipment involved, planned a journey of over four years. Another proposal included a trip to Mars, the use of that planet’s gravity to slingshot around for a visit to Venus, and following another slingshot maneuver, a triumphant trip home. The Mars missions were only abandoned when several failures of the heavy launch vehicles needed to get the equipment into space delayed the program. By then, the Americans had made multiple trips to the moon, and détente led to the joint Soviet-American orbital missions of the 1970s.

6. The Soviets built a space shuttle but never used it

In 1974 Leonid Breshnev learned of the American plans for a reusable space shuttle. He also learned of the potential military uses of such a vehicle. Convinced that the Soviet Union needed a space shuttle of its own, to counterbalance that of the American’s, he ordered the Russian space program to develop one. By then the Soviets were several years behind the Americans in planning. So, the KGB decided to acquire as much material as it could on the US version in development. What makes this one so baffling is the Soviets acquired virtually all the information there was on the space shuttle by simply buying it from NASA contractors and databases.

The Soviets acquired data on materials used in the shuttle, on its re-entry system and heat-resistant tiles, its booster rockets, and even the specifications for its tires. Nearly all of it came from commercial databases. It allowed the Soviets to quickly build their own space shuttle, which flew only once, unmanned. Not surprisingly, it was virtually indistinguishable from the American shuttle. Many of the documents were acquired by the Soviets though buying them through the US Government Printing Office. The Soviet use of American data and documents saved them millions in money and years of research and development, but the result never flew in space. The Soviet shuttle program ended after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

5. Laser pistols for cosmonauts

The Soviets feared the United States could use its space shuttle to steal communications and spy satellites, retrieving them via its robotic arm. Such a disruption of Soviet control was intolerable and a means of defending the satellites was required. How and when cosmonauts were to be dispatched to the threatened satellite is unknown, but they were to arrive at the scene of American treachery armed with laser pistols. Two different prototypes were developed. One was a magazine fed automatic, the other a revolver. Both were loaded with flashbulbs.

When fired by the cosmonauts, the flashbulbs ignited, emitting an intense burst of light through a garnet which when directed toward the eyes would inflict temporary blindness. The plan was to use them to disrupt light sensors as well. The automatic laser pistol contained a magazine which held eight flash rounds, the revolver six. Soviet developers claimed an effective range of around twenty meters (roughly 65 ½ feet). The weapon was still in the prototype phase when glasnost changed US – USSR relations and the laser pistols never entered production.

4. Anti-tank dogs

Between the World Wars the Soviets trained thousands of dogs for various roles in the Red Army, including as bomb carriers to attack enemy tanks. Ironically, the most frequently used breed of dog used was the German Shepherd. Initially dogs were trained to carry an explosive to the tank, plant the device beneath the vehicle, release it by pulling a strap designed for the purpose, and return to its handler for another mission. The bomb would be exploded by either a timer activated when the dog released it or via remote control. Few dogs could master the intricacies of the mission. Training shifted to have the dog’s mission be a suicide attack, with the bomb detonating on contact.

Trained dogs arrived at the front during World War II in 1941-42, where a new problem revealed itself. The dogs had been trained in their mission using stationary tanks, in order to conserve fuel. When dogs in the field encountered moving tanks they refused to dive beneath them as trained. Some returned to their handlers, where they exploded, inflicting casualties on nearby troops. Another problem was that dogs were trained using Soviet diesel-fueled tanks. The Germans used gasoline fueled tanks. Relying on their sense of smell, the dogs frequently attacked Soviet tanks. By the end of 1942 the anti-tank dog project was mostly over. It had not proven a good idea. Nonetheless, the Soviets continued to train dogs to attack tanks and other enemy vehicles into the 1990s.

3. The Caspian Sea Monster

At the time of its construction and throughout its ensuing career, an aircraft designated KM and so labeled on its wings claimed the title of the largest and heaviest aircraft in the world. Yet it wasn’t really an airplane. It was a flying boat which soared at extremely low altitudes using ground effects. Its designation, KM, appeared on its wings and hull, and stood for Korabi Maket, translated meaning Ship Prototype. Assigned to the Soviet Navy, it was classified as a ship, but operated by pilots of the Soviet Air Force. When US spy satellites detected its existence, the agency referred to the machine as the Caspian Monster, and later the Caspian Sea Monster.

Besides joking about it, the CIA launched an extensive espionage campaign to learn what it was and how the Soviets intended to use it. Eventually the giant aircraft/ship led to the development of another ground effects vessel for the Soviet Navy, only one of which was ever built. It was intended to carry troops, armor, and logistics support for a sea-borne invasion, essentially a self-contained D-Day invasion. The KM crashed during a test flight in 1980, years before the CIA learned what it was. The Soviets abandoned the project, and left the KM where it lay in the Caspian Sea until 2020, when the Russians moved it to Derbent with plans to include it in a military museum. Planning failures left the giant machine stranded just offshore. As of this writing, there it remains.

2. The Palace of the Soviets

In order to build the Palace of the Soviets in 1931, first the structure occupying the chosen site needed demolition. That building, the Cathedral of Christ the Savior, was first surveyed for valuables and other icons, which were removed and stored. Most of the costs of storage were assigned to a nearby monastery. The cathedral was demolished, and the Palace of the Soviets, which eventually had its design changed to make it the tallest skyscraper in the world, began to rise where the cathedral had stood. Construction began in 1937. When the Germans invaded the Soviet Union construction stopped, as steel suddenly had other, more important uses. The portions of the steel framework already erected came down, used by the Soviets for fortifications and railroads.

The giant poured concrete foundation remained, and eventually filled with water from ground seepage. In 1958 another use for the site was proposed. Since the foundation was a gigantic pool, it was decided to use it for that purpose. The Soviet hierarchy agreed. A two-year project cleared the debris of years from the site, and declared the foundation to be the Moskva Pool, touted by the Soviets as the world’s largest open-air swimming pool. After all, bigger is better. Eventually it was heated to allow it to remain open year-round. In 1994 the pool closed and the Russians built a new Cathedral of Christ the Savior on the site.

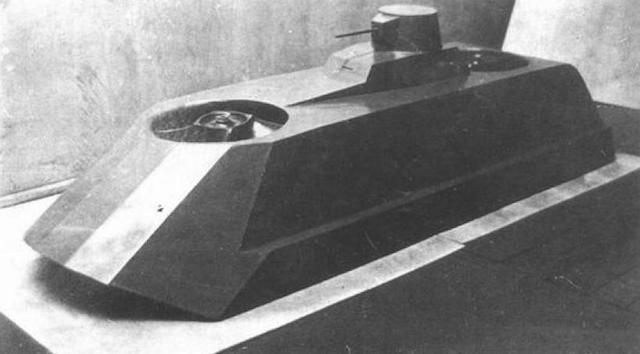

1. The amphibious hovercraft tank

In the 1930s the Soviets began work on a hovercraft tank. Because the machine relied on hovercraft technology for propulsion, it of necessity needed to be lighter than contemporaneous tanks (though it did have supplementary treads for propulsion in some terrain). That meant it needed to carry considerably less armor, making it vulnerable to enemy tanks. It also needed to carry lighter weapons than ordinarily deployed on tanks, making it less effective against those of the enemy. Nonetheless, its designers were enthralled at the vehicle’s ability to cross swampy, marshy ground without becoming mired in the muck. They also claimed it to be able to cross streams and narrow rivers without requiring a bridge.

The designers proposed a two-man crew, with one of them operating the vehicle’s single weapon, a .30 caliber machine gun. In the end, only a mock-up of the vehicle was built. The design team later proposed a more heavily built hovercraft armored car. In response to the stated belief that the hovercraft wouldn’t work on all terrain, they proposed equipping the armored car with wheels, but using hovercraft engines for propulsion, creating a non-hovering hovercraft. The Soviet Army didn’t bite. During the 1960s, a prototype hovercraft tank was built by the Soviets for testing, but the vehicle never entered production.