Headlines have been full of political sex scandals in recent years, but this is not a new trend. In fact, the worlds of politics and sex have often intertwined with controversial results, ever since ancient times. Today we take a look at eight political stories full of intrigue, action, scandal, murder, and even the occassional romance.

8. The Bona Dea Affair

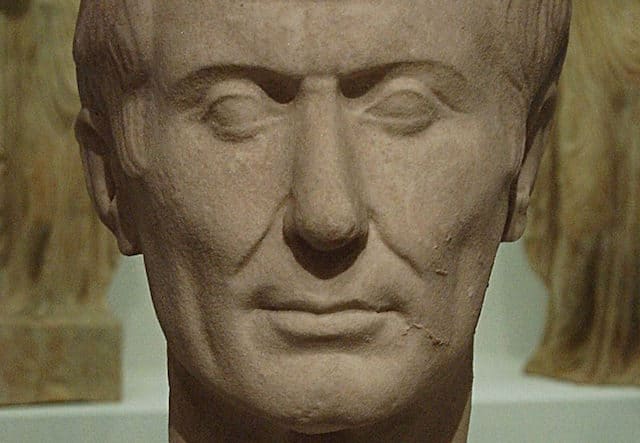

For this first entry we travel back to ancient Rome to look at a scandal that took place in the home of Julius Caesar, although it mainly concerned his wife, Pompeia.

Back then, there was a winter festival called Bona Dea where the rites were performed exclusively by women. In fact, men were not allowed to attend or even know of what happened during that sacred ceremony. Each year, the festival was hosted in the house of one of the senior magistrates and it was considered a great honor. In 62 BC, the ceremony took place in the home of Julius Caesar who, at the time, held the position of pontifex maximus. As was tradition, Caesar and all his male servants left for the day while his wife, Pompeia, and his mother, Aurelia, oversaw the festivities with the help of the Vestal Virgins.

In came a Roman politician named Publius Clodius Pulcher who wanted to witness the rites so he shaved his beard and dressed up as a lute girl and paid a servant to sneak him inside. He was discovered pretty quick when he had to speak to the other women in attendance. He was chased out of the house and the wives soon told their husbands of the great insult Clodius brought to them and to the gods.

Clodius was a pretty powerful politician and, consequently, he had enemies, among them Cicero. Rumors soon started spreading that Clodius committed adultery with his own sister, or that he infiltrated the ceremony that night to seduce Pompeia. He was indicted for sacrilege but was acquitted. Caesar divorced his wife when he heard about the rumors, although during the trial he said he knew nothing of what happened. When asked why he took such a drastic measure, then, the magistrate gave the memorable line that “Caesar’s wife must be above suspicion.”

7. The Tyrannicides

Staying in ancient times, we travel from Rome to Greece to examine the story of two male lovers named Harmodius and Aristogeiton who brought down the tyrants of Athens.

Back in 514 BC, the city of Athens was ruled by a tyrant named Hippias. He had a younger sibling named Hipparchus who also held a high position, although what it was exactly depends on the source. Some said he was a minister while others insisted that he served as co-tyrant alongside his brother. For clarity, back then the word “tyrant” didn’t necessarily have the negative connotation it has today as it simply meant a person who took power without a constitutional right.

Anyway, Hipparchus fell in love with a young man named Harmodius, but the feelings were not mutual as Harmodius was already in a relationship with another man named Aristogeiton. Hipparchus kept insisting and the two lovers started fearing that the statesman would use his power and influence to get Aristogeiton arrested, even killed, so that he could be with Harmodius. They decided they had to get rid of Hipparchus. They would do it during the Panathenaea, a festival dedicated to Athena full of music, sports, and religious ceremonies. More importantly, it meant that Hipparchus would be out in the open.

According to historian Thucydides, the lovers found conspirators to aid them, but the main goal became to kill Hippias and bring down the tyranny. On the day in question, Harmodius and Aristogeiton saw one of their conspirators being friendly with the Athenian tyrant and thought that their plot had been exposed. Not wanting to go down without a fight, they reasoned that they could, at least, get some personal vengeance, and attacked and killed Hipparchus. They were both killed, Harmodius on the spot and Aristogeiton after being tortured.

Afterwards, Hippias became a much crueler ruler and was eventually overthrown, becoming the last tyrant of Athens. The two lovers who became known as the Tyrannicides had statues erected in their honor and were hailed as heroes for helping to usher in Athenian democracy.

6. John Wilkes’s Essay

John Wilkes was an 18th century British Parliamentarian who was involved in not one, but two sex scandals and eventually had to flee to France to escape prison.

It all started in 1762 when John Stuart, the Earl of Bute, became the Prime Minister of Great Britain under King George III. Wilkes, who was a radical, wasn’t a fan of the Scottish earl and started besmirching the new Prime Minister in the newspaper he published, the North Briton. He began alleging that Stuart only got the job because he was having an affair with the king’s mother. In 1763, this got Wilkes charged with seditious libel, but he was released on the grounds of parliamentary privilege.

By this point, Stuart had actually already been replaced as Prime Minister with George Grenville, but Wilkes wasn’t the kind to quit while he was ahead. His new intention was to test how far the liberty of press extended in England. He wrote “Essay on Woman”, an obscene and pornographic parody of “Essay on Man” by Alexander Pope. Moreover, he had it read during a parliamentary session.

Again, this was deemed libel but, at the same time, plans were set in motion to oust Wilkes from Parliament so that he would lose his immunity. He was expelled from Parliament, but fled to France before being arrested. He stayed there for four years before returning to England and serving his prison sentence.

5. The Affair that Toppled a King

Sweden saw its own sex scandal during the 13th century that led to the fall of a king.

King Eric IV of Denmark had four daughters. The eldest two, Sophia and Ingeborg, were married off to other kings. In 1260, Sophia married Valdemar who had ascended to the throne of Sweden. There were still two daughters left but, fearing the loss of lands that would result from dowries and inheritances, it was decided after King Eric’s death by the Danish regent that the younger sisters would become nuns.

This did not sit well with Jutta, one of the princesses, who found the monastic life quite dull. At one point around 1269, her sister Sophia, now the Queen of Sweden, paid a visit to her native land and Jutta persuaded her to take her along to the Swedish court. There, Jutta started having an affair with King Valdemar and even had his child.

The romantic tryst was scandalous enough, but add to that the fact that it involved a nun who was the queen’s sister and she also gave birth to a child and it was enough to turn the people against Valdemar. According to some sources, the king made a pilgrimage to Rome in 1274 to ask the pope for forgiveness, but this backfired when Pope Gregory X made great demands in exchange for his absolution.

The fact that Valdemar agreed to these concessions made him even more unpopular back home and, a year later, his brothers Magnus and Eric rebelled against him. They met at the Battle of Hova on June 14, 1275, where the siblings were triumphant. Valdemar was deposed and Magnus became the new King of Sweden.

4. The Premier and the Secretary

We now go to Canada to look at a scandal that not only brought down a prominent politician, but also his entire party.

During the 1930s, John Brownlee was the Premier of Alberta while his party, the United Farmers of Alberta, had formed the provincial government ever since 1921. Then, in 1933, he stood accused of seducing a young woman named Vivian MacMillan and forcing her into a love affair that lasted for three years and caused her physical and emotional trauma.

In 1930, Brownlee visited the town of Edson where MacMillan’s father was mayor. That was where he met 18-year-old Vivian. He convinced her to move to Edmonton and promised her a stenographer’s job. Soon after she did, Brownlee asked that she had sex with him, claiming that he could not risk intercourse with his disabled wife because pregnancy could kill her. Reluctantly, MacMillan agreed, saying that the premier would threaten to take away her job whenever she refused one of his lustful impulses.

The affair carried on for a few years until 1932 when MacMillan suffered a nervous breakdown and she returned home to Edson to rest. As soon as she was back in Edmonton, Brownlee insisted that the two resumed their activities. Vivian also had a fiancee, but he rescinded his offer of marriage once he found out about the affair.

This was all Vivian’s side of the story. According to Brownlee’s version, the whole thing was a lie fabricated by the MacMillans and his political opponents in the Liberal Party. He could even prove that on certain occasions when the couple allegedly met, the premier was out of town on business.

Brownlee was sued for $10,000 for seduction and the jury ruled in favor of Vivian. However, in another controversial move, the judge in the case, W. C. Ives, overturned the verdict by reason that the plaintiff failed to show that she had suffered any damages.

This made no difference to Brownlee’s career. He resigned as premier immediately after the jury’s verdict. During the next provincial election in 1935, his party lost every single seat that was up for re-election.

3. The Cleveland Street Scandal

In July of 1889, London police were investigating a routine theft from the city’s Central Telegraph Office. What they discovered was anything but routine and caused one of the biggest scandals in Victorian England, implicating some of the country’s leading aristocrats.

On July 4, a 15-year-old telegraph messenger boy named Charles Swinscow was brought in for questioning after police found 18 shillings on him which represented about a week-and-a-half’s wages. They wanted to know why he had so much money on him, obviously suspecting him of being involved in the theft. As it turned out, Swinscow did not steal that money. He made it by prostituting himself to London’s elite. The youth identified several telegraph boys who told the same story – they were recruited by a man named Charles Hammond who operated a male brothel at 19 Cleveland Street. His clientele consisted entirely of rich and influential men from England’s upper classes – peers, politicians, and journalists.

The case went to Chief Inspector Frederick Abberline, best known for investigating the murders committed by Jack the Ripper. He made some arrests, but they were all small time. The telegraph boys and some of the men who helped run the brothel were given lenient sentences, but Charles Hammond managed to flee the country and none of his clients were arrested or charged with anything.

It is generally believed that everyone in Parliament and the Royal Family did everything they could to cover up the scandal. It was mainly a small radical newspaper called The North London Press that kept the affair going, plus foreign press, mainly the French, who could cover the subject and name names without fear of reprisals.

Lord Arthur Somerset, the head of the stables for the future King Edward VII, was the one most frequently named in the scandal and, allegedly, also the person who helped Hammond escape justice. Eventually, he was forced to flee England and settle in France. Up to 60 other men were named at various points, but there was never any concrete evidence to back up the accusations. At least, none that became public knowledge.

Without a doubt, the most high-profile person alleged to have been involved was Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence and grandson of Queen Victoria. He was the same royal who was put forward as a potential suspect for Jack the Ripper.

2. Death at Venus’s Altar

During the late 19th century, Marguerite Steinheil was one of the most desirable women in France. In fact, she became known for her many affairs with rich and powerful men, but none was more notable than her liaison with Félix Faure, the President of France, who allegedly was having sex with Steinheil when he keeled over dead.

The president met Marguerite Steinheil in 1897 and began a love affair that lasted for two years. As the mistress later described their encounters, whenever Faure wanted to meet for a rendezvous, he would send a private detective to bring Steinheil to the palace. She would enter through a small door overlooking the gardens and make her way to the drawing room where Faure would be waiting. As far as everyone else was concerned, Steinheil’s function was that of the president’s “psychological advisor.”

Félix Faure died on February 16, 1899, of apoplexy. Steinheil had visited him that day, although whether or not the two were in the middle of a lover’s embrace when the president suffered his stroke is still a matter of debate. It didn’t matter to the media, though. Just the fact that Steinheil was there made the story way too juicy to bog down with minor details like the truth. One newspaper wrote that the president died “from an excess of good health.” Another said that he was sacrificed on the altar of Venus.

Perhaps the most ingenious put-down came courtesy of Faure’s political opponent Georges Clemenceau who wrote of the president “Il voulait être César, il ne fut que Pompée.” This is a pun in French which can be read either as “He wanted to be Caesar, but ended up as Pompey” or “He wanted to be Caesar, but ended up being pumped.”

1. The Queen and the Eunuch

We end our trip through the licentious parts of political history in ancient China to look at a scandal that took place right at the time of the unification of the country. During the Warring States period, Ying Zheng was a prince of the Qin state who would later go on to become Qin Shi Huang, the first Emperor of China. We, however, are not concerned with him, but with his mother, the Queen Dowager Zhao Ji.

This story comes to us courtesy of the Records of the Grand Historian, one of the most important works on Chinese history by ancient historian Sima Qian. Some modern scholars doubt its veracity but, according to Sima, Zhao had an affair with a powerful merchant named Lü Buwei. As his influence increased, so did his responsibilities and Lü had to be away from the palace and his lover more and more. But Zhao had an unstoppable lust and Lü became concerned that she might do something to expose their affair. So he found her a replacement lover, one who could be at her side whenever she was feeling frisky.

His name was Lao Ai and, apparently, he was so well-endowed that he could walk around with a wheel rotating on his erect penis. In order for Lao Ai to be allowed to stay by the queen’s side, he was shaved and presented as a eunuch.

The queen was quite happy with this arrangement and, allegedly, she even had two sons with Lao Ai. Eventually, however, they were discovered. Lao Ai tried to stage a coup against Qin Shi Huang, but it failed miserably. Lao was torn apart by horses while his followers and his two sons were executed. The queen was imprisoned in the palace and Lü was banished, later committing suicide.