Harriet Tubman is well known in the United States as an escaped slave and abolitionist, and as someone who led other escaping slaves to their freedom along the Underground Railroad. But much of what is known about her is untrue. Her exploits have been exaggerated over the years for political purposes. Some of the exaggerations began during her own lifetime. She is credited, if that is the word, with gathering escaped slaves in Canada to join John Brown’s raid at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, in 1859, for example. Yet Brown’s raiding force included just five blacks, only one of whom was a former slave. None were from Canada.

Her exploits were exaggerated by abolitionists in the North, who found Tubman useful in forwarding their own work. Various claims of substantial rewards offered for her capture, some of them with the stipulation “dead or alive,” can be found today, though no contemporaneous evidence of such rewards have ever been found. The only provable bounty ever offered for her was $100 for her return as an escaped slave. Her illiteracy rendered her incapable of recording her own story, though she told it to interviewers, family, and friends, with it changing often as the years went by. Today, we’ll look at the veracity of 10 common myths about Harriet Tubman…

10. Myth: She hid escaping slaves in a safe house owned by Jacob Jackson

Jacob Jackson was a free black man who owned and farmed roughly 130 acres of land on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. It is often reported that Tubman wrote letters to Jackson, and that he maintained a safehouse on his property, a stop on the Underground Railroad. Jackson was suspected by slave owners in the area of assisting in the flight of runaway slaves, and his house was frequently visited by self-appointed inspectors, which made it too dangerous as a temporary stop for runaways. Jackson’s role in the Tubman saga was as a messenger, relaying the time appointed by Tubman for slaves to begin their escapes.

Neither Jackson nor Tubman could read or write, making communication by letter difficult. Tubman dictated her instructions to accomplices in the North and the letter was delivered to Jackson by men who had to read it to him. The arrangement meant that communications had to be made in a manner understood only by the two of them, since the letter would be read aloud, usually by the same inspectors who were already suspicious of Jackson. On one occasion, Jackson conveyed the message from Harriet to her brothers to meet her at an appointed time and place, after which she led them to freedom in Pennsylvania. How many other times the two worked together, or if they did, is unknown.

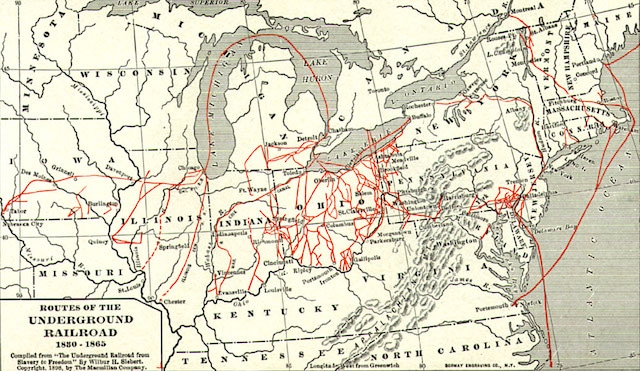

9. Myth: Harriet Tubman traveled all over the south to lead slaves to freedom

There is a widespread belief that Harriet Tubman traveled all over the pre-war South, leading hundreds of slaves to freedom in the North, with many of them traveling all the way to Canada. While many escaped slaves did travel to Canada (due to the existence of the Fugitive Slave Act), those led to freedom by Tubman came from Maryland. She made 13 individual trips to Maryland’s Eastern Shore, from which she helped about 70 slaves escape to freedom. Most were family and friends. Those numbers were given by Tubman herself to her biographer, Sarah Bradford.

It was the abolitionist newspapers of the day, and later those Northern newspapers which supported the Lincoln administration’s goal of ending slavery, which inflated both the number of trips Harriet made and the number of slaves she led to freedom as a conductor on the Underground Railroad. Scenes in the Life of Harriet Tubman (1869) was followed by a second work by Bradford, Harriet, the Moses of Her People (1886). The two works are the source of many of the myths which exist about Tubman today. A scholarly biography about Tubman did not appear until 1947, though there were numerous children’s books written about her before then.

8. Myth: She used the quilt code to follow the Underground Railroad

The idea of escaping slaves using a code displayed by hanging quilts, which delivered instructions on when and where to move, did not emerge until 1998, when it was presented in the book Hidden in Plain View: A Secret Story of Quilts and the Underground Railroad. The theory was overwhelmingly dismissed by historians and scholars, citing lack of documented evidence, lack of contemporaneous evidence, and the fact that no quilts containing the designs cited by the book’s authors have ever been found. Probably the single biggest reason to dismiss the idea of Harriet Tubman following the quilt code is that neither she, nor any of the slaves she helped to escape, ever mentioned it themselves.

Harriet navigated her way through her knowledge of the Eastern Shore, which she developed during her youth, and through contact with trusted fellow conductors and supporters of the Underground Railroad. She avoided contact with those people who were unknown to her. Most of her contact with others was direct, necessary because written messages were meaningless to her, as they were to most of the slaves she helped escape. She relied on several of the subterfuges of someone in hiding, including wearing disguises, accepting the help of others who gave shelter, and relying on their guidance to elude slave catchers.

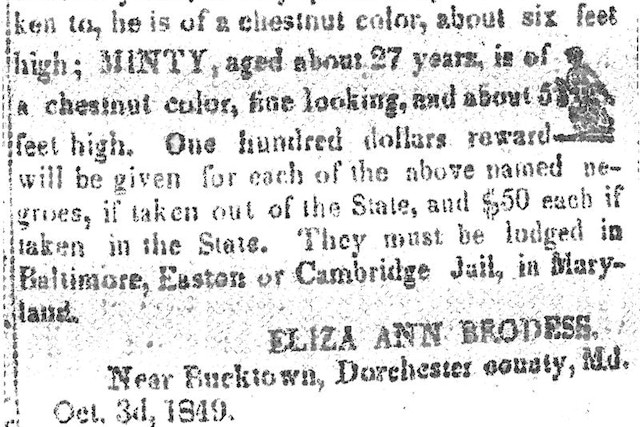

7. Myth: She had a $40,000 bounty on her head for her capture, dead or alive

To date, no evidence of any ‘bounty’, in any amount, being offered for the capture of Harriet Tubman has been found. The slave owners of the region had no reason to suspect that the escaped slave they knew as Minty Ross was helping others escape. There was a reward for Minty Ross, as well as for her two brothers, but it was for their return to slavery and it was offered if they were recaptured outside of Maryland. Eliza Brodess, their owner, offered $100 for each of them. The oft-repeated amount of $40,000 offered for Tubman cannot be called an exaggeration. It was simply a lie, created for effect.

Sarah Bradford included a lesser amount in her first work on Tubman, claiming that it was $12,500, and that when Tubman was asked about the amount of $40,000, she replied that she had not heard of it being that much. Bradford included it anyway, along with opining that it could have been much more. A reward of that amount, equivalent to over half a million dollars in today’s money, would likely have been reported in every newspaper in the country. It was not.

6. Myth: She sang numerous songs as signals

The myth that Tubman sang certain songs as signals grew over the decades, as oral histories passed down by succeeding generations were subject to changing memories and family traditions. She did sing, upon approaching rendezvous points, as a means of signaling to those escaping that it was time to move. She told Sarah Bradford which songs she sang, listing only two: Bound for the Promised Land and Go Down Moses. Those two should be enough, but those choosing to mythologize Tubman use other spirituals as replacements for the songs Tubman, and her charges, would have known.

Swing Low, Sweet Chariot was written in Oklahoma’s Indian Territory circa 1865 by a Choctaw of the name Wallis Willis. Willis, a former slave (it is often forgotten in America that many Indians were also held as slaves) did not read music; the song was transcribed by Alexander Reid, a minister. Follow the Drinking Gourd, which refers to the Big Dipper, may have been a song known at the time (it was first published in 1928), but Tubman herself did not refer to it in her story to Bradford. The legend of using the song developed on another route of the Underground Railroad and later became absorbed into Tubman’s story.

5. Myth: Araminta was her true African name

In more recent reports of the myths surrounding Harriet Tubman, Araminta is referred to as her real name, and in some cases as her “true African” name. Araminta was the name bestowed upon her by her parents, and she was known in the vicinity where she grew up, and later from which she helped slaves escape, as Minty Ross (Minty being a diminutive of Araminta). Araminta was not an African name, but a common name for women, especially Puritans, in North America and England for many years. Today it is relatively rare.

It was common enough in the 19th century that Mark Twain used it as one of the names for Tom Sawyer’s cousin in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Minty Ross, as she was known, adopted the name Harriet Tubman, with the surname being that of her husband for a time, John Tubman. She continued to be called Minty by family and friends; she appeared — or rather some of her exploits appeared — as Harriet Tubman in the abolitionist newspapers of the north. She could not use her real name for fear of retaliation against family members still enslaved in Maryland.

4. Myth: She was forced to marry John Tubman

In Maryland of the 1850s about half of the black population was free, though slavery remained legal in the state. John Tubman was a free man when he married Minty Ross sometime around 1844. Such an arrangement was fairly common in Maryland; slaves required the permission of their owners to marry a free person. When Tubman married Ross, he freely surrendered the rights to any children issuing from the marriage. They would, under the law, become the property of Minty’s owner. It was following the marriage to Tubman that Araminta changed her name to Harriet.

Harriet left her husband behind when she escaped from slavery, returning some years later to find him living with another family, happily remarried. He had no desire nor intention of fleeing to the North with Harriet, and as a free man he could have left long before. Harriet, on a later trip, left with a girl she claimed was her niece, but who may in fact have been her daughter with John Tubman. Harriet remarried in New York after the Civil War, and John Tubman faded from the scene. Her marriage with Tubman was not forced upon her, by either he or her owner.

3. Myth: Tubman had 11 brothers and sisters

Harriet Tubman was born to Harriet (known as Rit) and Ben Ross, though the exact location of her birth is uncertain. Rit was a cook for the Brodess family; Ben was a timberman and woodsman, held by Anthony Thompson, who owned a nearby plantation. Together, Ben and Rit had nine children, including Araminta. Araminta eventually had four brothers (three of which were younger than her) and four sisters. When she was young, her three eldest sisters were sold by their owner, Edward Brodess, and Minty lost all contact with them.

Her father was frequently absent, managing the timbering operations on Thompson’s plantation, and her mother was too busy with her work in the Brodess home to spend much time with her own family. Minty was required to care for her younger siblings until she was hired out as a babysitter when she was, according to her recollections to Sarah Bradford, five or six years of age. It was a position in which she was first beaten as a slave (again according to Bradford) and where she first learned to resist her owners’ in a variety of ways, including running away.

2. Myth: She was born on the farm owned by Edward Brodess in Maryland in 1820

Harriet Tubman’s date of birth can be listed as one of several, depending upon the source. Tubman later claimed that she was born in 1825. Other historians dispute that date, claiming that she was born in 1820, 1822, 1824, and other dates. Her certificate of death lists her birth year as 1815. Her tombstone reads 1820. The fact of the matter is her year of birth is an estimate, with no definite indication of when it was.

The same is true of her place of birth. She could have been born on the smaller farm owned by the Brodess family, or the larger plantation nearby owned by Anthony Thompson. Since her mother worked in the Brodess home as a cook, it is most likely she was born on the Brodess farm, though midwife records indicate that she could have been born on Thompson’s plantation in 1822.

1. Myth: She led over 300 slaves to freedom in the north

Several sources claim Harriet Tubman led hundreds of slaves to freedom in the North before the Civil War, greatly exaggerating her achievements. In fact, she led about 70, in the course of 13 trips to Maryland. Nearly all of the freed slaves came from Dorchester County, from whence she had herself escaped. The names of nearly all of them are known. So are many of the agents and conductors on the Underground Railroad who helped her on her journeys.

After the war, Tubman told her story to Sarah Bradford, who published it with the intent of raising money for the impoverished subject of the tale. It was successful. Many of the exaggerations which embellish her achievements were born at that time. Her achievements don’t need any embellishment, and masking them with myth does a disservice to a remarkable heroine of American history.