It’s hard to believe that there are 7.8 billion people on the planet, and that number isn’t getting any smaller anytime soon. The United Nations estimates that by 2050, the world’s population will reach 9 billion. As other species go extinct at record rates, human beings show no signs of slowing down. So it might seem a little strange that there was a point in time where human beings were the ones who nearly vanished from the planet. Here are five facts about humanity’s near-extinction in 70,000 BC…

5. There May Have Been Only Forty Breeding Pairs

A study led by molecular biologists at Oxford has concluded that human beings were once reduced to roughly a thousand reproductive adults, while author Sam Kean believes he’s found evidence that suggests that number dips to only forty. It’s hard to fully take in this fascinating revelation because of its implication. How could only a thousand breeding pairs expand to 7.8 billion people? Bottleneck effect.

More recently, Northern elephant seals have fallen victim to it as well. During the 1890s, as a result of relentless poaching by humans, the seals’ population size was reduced to as few as 20 individuals. Naturally that led to a reduced genetic variation in the Northern elephant seal population. Since their near extinction, Northern elephant seals have seen their population rebound to over 30,000; however, they still have the effects of the bottleneck. Southern elephant seals have far more genetic variations than their cousins in the north, because they were not as intensely hunted.

4. What Caused Our Bottleneck?

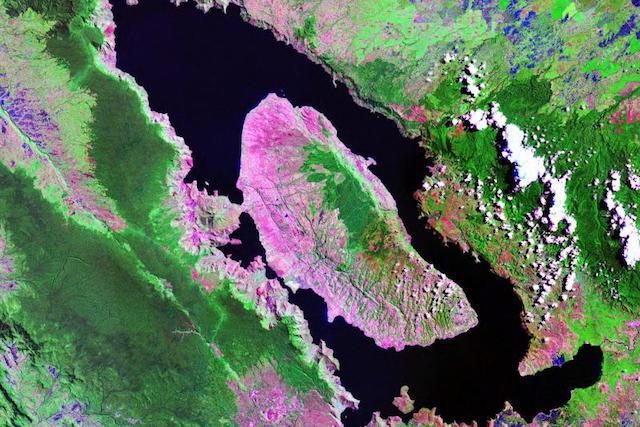

Around 70,000 BC, a volcano called Toba, in Indonesia, erupted. It wasn’t an ordinary volcano. Roughly 650 miles of vaporized rock was blown into the air. It’s considered the largest volcanic eruption that we know of, and it’s not even close.

To put Toba into perspective, in 1980, Mount St. Helens ejected 1 cubic kilometer of rock. In 79 CE, Vesuvius ejected 3 cubic kilometers of rock and material, and in 1815 the Tambora eruption unleashed an unholy 80 cubic kilometers. The Toba eruption? An unfathomable 2,800 cubic kilometers of material. The layers of ash that erupted from Toba are still visible all over South Asia and the Indian Ocean.

3. Our Near-Extinction

With the Toba eruption ejecting so much material into the air, dust and ash settled high in the sky, likely dimming the sun for up to 6 years. It’s not hard to imagine how difficult and unpleasant life on Earth with a dimmed sun would be, but for early humans it proved nearly fatal. The lack of sunlight and the effects of the eruption disrupted seasonal rains, choked off streams, and even made berries, trees, and fruits scarce. Hot ash pummeled trees and forests, leading to mass starvation as human beings struggled to find sustenance in an environment where food was buried under the remains of Tuba’s eruption. Many scientists believe that this was the period in which the human population experienced the bottleneck effect.

Some have argued that with the ash hanging in the air, a cold planet got even cooler. The plains of East Africa may have dropped 20 degrees in temperature, causing even further hardship to the small band of surviving humans.

2. Our Eventual Expansion

Most good stories have the lowest moment before there triumph, and humanity’s story is no different. After nearly going extinct, human beings have rebounded in a major way, but it wasn’t an overnight expansion. It took us more than 200,000 years to reach a billion people in 1804. As they say, the first billion is the hardest to make, and since then we’ve been on a tear. We reached 3 billion by 1960 and it’s been nearly a billion more human beings added to the planet every 13 years.

With how much we’re growing, many people have become worried about our ability to combat threats that may arise as we continue to demand more and more of the planet’s resources. Some argue that climate change is the biggest threat to humanity; others have argued that diseases that were once isolated in the forest may now become exposed to all of humanity. It’s hard to know exactly what will be humanity’s next big threat, but if we managed fight off extinction before, we’ll likely do it again. At least some of us will.

1. We May Still Go Extinct… Just Not For Awhile

There are some within the scientific community who not only believe that human beings will go instinct, but that they have a pretty good idea when it will take place. Recently, the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists warned that “the probability of global catastrophe is very high.” They have called nuclear weapons and climate change “humanity’s most pressing existential threats.” With world leaders unwilling or unable to tackle humanity’s biggest problems, it’s not unreasonable to wonder how long we can go on like this. Life on Earth has already experienced five mass wipeouts, the last one occurring 252 million years ago. Known as “The Great Dying,” the disaster killed off 95% of marine life when the oceans became acidic. Geophysicist Daniel Rothman believes we are seeing a disturbing, yet similar parallel today, this time caused by global warming. Rotham argues that the oceans will soon hold so much carbon that extinction will become inevitable. By 2100, Rotham predicts a mass extinction that will destroy human civilization will begin.

Another reason that many scientists believe that extinction is likely is because of our inability to make contact with other forms of intelligent life. The elements of life are abundant in the universe, which means that if the conditions are right, intelligent life is likely to arise on other planets, as it did on Earth. Why haven’t we made contact? Some have suggested that intelligent life is inherently self-destructive and that other forms of intelligent life have not made contact because they have destroyed themselves. If all other forms of intelligent life have, in fact, orchestrated their own demise, who are we to be any different?