Today we take a look at a few bloody chapters from the history of crime. In one way or another, all of these cases shocked, repulsed, and thrilled the public in their day, but they all had one thing in common – none of these murders were ever officially solved.

8. The Hinterkaifeck Murders

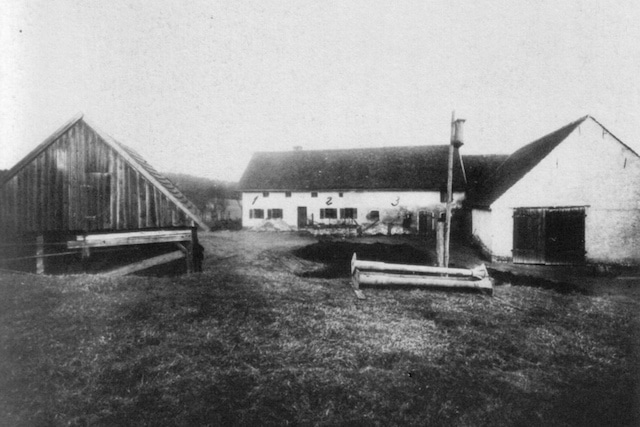

In the early 20th century, there was a little farmstead situated roughly halfway between the German towns of Ingolstadt and Schrobenhausen in Bavaria. It belonged to the Gruber family and was known as Hinterkaifeck. Andreas Gruber lived there with his wife, his adult daughter, two young grandchildren and a maid. On March 31, 1922, all six of them were killed with rusty farm tools. Who did it and why remains a mystery to this day.

After a while, the locals began to notice their absence. The entire family missed church on Sunday and young Cäzilia hadn’t attended school several days in a row. Eventually, a few of them went to the farmstead where they discovered the horrid scene. Most of the Grubers had been murdered in the barn, presumably lured inside one at a time. The maid, Maria Baumgartner, and the 2-year-old baby, Josef Gruber, were killed inside the house.

At first, police suspected one or more vagrants, but dismissed this idea since the house had not been disturbed and money was left where it was. Even more curiously, the killer or killers spent time at the farm after the murders, lighting fires, eating food and even feeding the animals.

Afterwards, suspicions were directed towards some of the locals, particularly one Lorenz Schlittenbauer who was rumored to be the father of young Josef Gruber. An even more sordid rumor said that Andreas Gruber was actually the father of his own grandchild after having an incestuous relationship with his daughter Viktoria. Lastly, there was Viktoria’s actual husband, Karl Gabriel, who was purportedly killed in World War I, but one hypothesis claimed he survived, returned home and killed the family in anger when he found out that his wife had a baby with another man.

These are just three of the more pervasive notions regarding what happened at Hinterkaifeck. There are many more, but no evidence to prove any of them.

7. The Green Bicycle Case

On the night of July 5, 1919, 21-year-old Bella Wright was shot and killed outside a tiny English village called Little Stretton in Leicestershire. The only clue the police had to go on was that she was seen earlier that evening in the company of a man riding a green bicycle.

This might sound like the setup for a mystery novel, but it ended up becoming one of England’s most notorious and most controversial murders of the early 20th century. The controversy stemmed from the fact that the authorities always had a solid suspect. His name was Ronald Light. He was 33 years old and not only did he own a green bicycle, but he tried to get rid of it after the crime. He also threw away a pistol holster with bullets that matched the one that killed Bella Wright. Lastly, he reluctantly admitted to being the man on the green bicycle that night, after eyewitnesses identified him.

All of this built a strong case for Light’s guilt and yet, he was acquitted in 1920. His attorney, the venerable Sir Edward Marshall Hall, pointed out that all the circumstantial evidence merely indicated that Light and Wright rode together that night for a while, something which his client had already admitted. None of it suggested that Light had anything to do with Wright’s death or that he was even present at the time.

The main scenario advanced by Hall was that the young woman was killed by a ricochet from someone hunting in a nearby field. He argued that a close range shot would have caused a lot more damage to the face, whereas the actual bullet hole was so small that the first doctor who inspected the body missed it.

Moreover, he pointed at Light’s complete lack of motive for the killing and he even put his client on the stand to testify and show off his calm demeanor and soft-spokenness. Clearly, he won over the jury who unanimously agreed that Ronald Light was not guilty. Ever since then, crime buffs have been left to wonder on what happened that night.

6. The Texarkana Moonlight Murders

We move on now to the unsolved case of a serial killer active in the United States decades ago. He preyed on young couples in secluded areas. He killed five people that we know of. He shot all of his victims, but some of them survived. He was never identified so he was referred to by a nickname in the media. The police did have one solid suspect, but could never positively tie him to the murders.

Some of you crime buffs might be spotting a lot of similarities to the notorious Zodiac murders but, in fact, we are talking about a string of killings that occurred over two decades prior and are mostly forgotten today while the Zodiac still remains one of America’s most notorious criminals. They were the Texarkana Moonlight Murders, perpetrated by someone dubbed by the media the “Phantom Killer” or the “Phantom Slayer.”

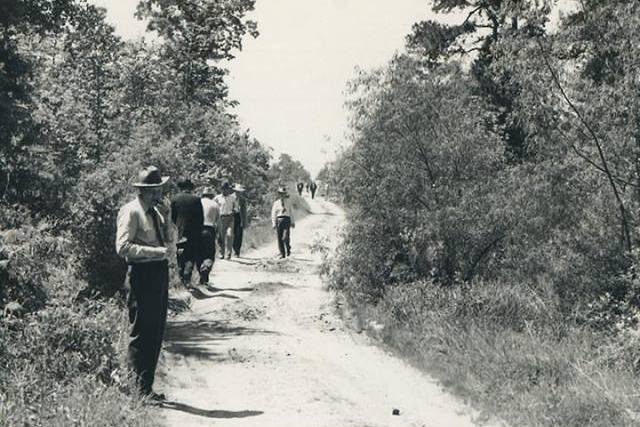

The murders occurred in and around the sister cities of Texarkana, Texas, and Texarkana, Arkansas, between February and May of 1946. They were investigated by the Texas Rangers who suspected a man named Youell Swinney of the killings. He was a lifelong petty criminal and it was his wife who first brought him to the police’s attention, although she later refused to testify against him. Swinney was imprisoned the following year, but on unrelated car theft charges. Eventually, the trail went cold, investigators moved on to other cases, and the identity of the Phantom Killer remained a mystery.

5. The Beautiful Cigar Girl

Fans of detective stories might be familiar with The Mystery of Marie Rogêt by Edgar Allen Poe, featuring his crime-solving sleuth, C. Auguste Dupin. What they may not know was that Poe’s story of the murder of a perfume saleswoman in Paris was based on the actual murder of Mary Cecilia Rogers from New York City.

Twenty-two-year-old Mary Rogers disappeared on July 25, 1841, and her body was found three days later in Hoboken, New Jersey, floating in the Hudson River.

Mary Rogers was considered a very beautiful young woman and the tobacco store where she worked as a clerk was often filled with men who bought something just so they could flirt with her. Therefore, her death caused a frenzy as the media dubbed her the “beautiful cigar girl.”

Truth of the matter is that we cannot even say with certainty that she was murdered. After three days in the water, her remains were damaged and swollen. There were extensive bruises on her body, and what looked like a ligature mark on her throat, both which suggested that she had been assaulted. In fact, the most popular theory of the police at the time was that she had been a victim of gang violence. Other ideas suggested that Mary died during a failed abortion or that her fiancé, Daniel Payne, was involved. Payne allegedly had an airtight alibi for the night of her death, but remained a suspect in the public mind after committing suicide a few months later and leaving behind a note asking forgiveness for his “misspent life.”

Eventually, once all the sordid details were out in the open, people started to lose interest and the newspapers moved on to the next story, leaving the death of Mary Rogers unsolved to this day.

4. The Shimoyama Incident

In 1949, Japan experienced three deadly incidents involving its railway system. A train was derailed in Fukushima. Another one was crashed into Tokyo’s Mitaka Station. And lastly, our focus today, the first president of the Japanese National Railways, Sadanori Shimoyama, disappeared on July 5 and was found the following day, his body severed after being run over by a train.

Obviously, given the temporal proximity between the three events, many immediately suspected that Shimoyama’s death was caused by the same group of people responsible for the other incidents. Those who believed the three were connected generally suspected radical union members who were also affiliated with the Japanese Communist Party.

Even if they weren’t involved, there was a very long list of people who may have wanted to harm Shimoyama. As the president of the railway network, he was responsible for personnel cutbacks that saw tens of thousands of workers lose their jobs. This gave investigators a giant suspect pool, but also a motive for possible suicide. Some believed that Shimoyama killed himself due to stress and guilt over the layoffs.

Authorities of that time conducted a tight-lipped investigation. Eventually, they closed the case without any arrests and never disclosed any details. It wasn’t until in recent decades that hundreds of documents from the investigation were made public, but it brought us no closer to solving Shimoyama’s death.

3. The Ardlamont Mystery

For this case we travel to Argyll, Scotland, to Ardlamont House, the estate that once belonged to the Hambrough family. In 1891, the family accepted a new person into their ranks – 30-year-old Alfred John Monson who was there to serve as gentleman’s tutor for 18-year-old Cecil Hambrough.

Two years later, on August 10, 1893, Monson took Cecil for a day’s hunting. Accompanying them was an acquaintance of Monson named Edward Scott. At one point, shots rang out of the forest and the servants then saw only Monson and Scott returning back with the guns. The duo claimed that Cecil Hambrough had accidentally shot himself in the head by discharging his weapon while climbing a fence.

An investigation was launched immediately, but there was no suspicion of foul play at first as there was seemingly no motive. A few weeks after Cecil’s death, however, authorities discovered that just a few days before the shooting, the young aristocrat took out two life insurance policies and, for some reason, named Monson’s wife as beneficiary. Now there was a motive so police arrested Monson and charged him with murder, while his accomplice, Edward Scott, went on the run.

The trial itself was notable for featuring the testimony of Joseph Bell, the Scottish surgeon who inspired Arthur Conan Doyle to create Sherlock Holmes. He was of the opinion that Monson had shot young Cecil Hambrough. Even so, Alfred Monson was acquitted after the jury returned with the Scottish verdict of “not proven,” used in Scots law when neither side can definitively make their case.

The story of the Ardlamont murder had a strange epilogue the following year. Because the case was infamous in its time, Madame Tussaud, the wax museum in London, created a waxwork of Alfred Monson and placed it in the Chamber of Horrors alongside other notorious killers. He successfully sued them for libel and established a legal precedent that wax figures can give rise to libelous accusations.

2. The Murder of Moll McCarthy

On November 21, 1940, Mary “Moll” McCarthy was gunned down in her rundown old cottage in Marlhill, a small village in County Tipperary, Ireland. Some time later, a neighbor by the name of Henry Gleeson, usually referred to as “Harry,” found her body and reported her death to the police. Gleeson was subsequently arrested, convicted and hanged for the murder of Moll McCarthy.

It all sounds like a brutal, but straightforward case. Gleeson even had a motive. McCarthy occasionally worked as a prostitute and had several children by multiple men. Gleeson was said to be one of them, except that his child died in infancy, so he killed McCarthy out of anger.

And yet, in the decades since the crime occurred, it came to be regarded as one of the most egregious miscarriages of justice in Irish history as more and more people lobbied for Gleeson’s innocence. It culminated in 2015 when, for the first time in the state’s history, the President of Ireland gave him a posthumous pardon.

All signs suggested that the authorities executed an innocent man, but then who was the real killer? The other fathers of McCarthy’s children would have made strong suspects, considering that many of them were married. Unsurprisingly, given the way the case was handled, there was also talk of a coverup. Crime buffs suggested that the real culprit could have been a member of the local Gardai or the IRA, with Gleeson serving as a convenient patsy.

1. The Teal Pond Mystery

The early ’90s saw the premiere of a surreal and captivating show called Twin Peaks, centered around the mysterious murder of a young woman named Laura Palmer. However, the inspiration for the show came from a scary story that co-creator Mark Frost heard from his grandmother when he was a boy – the real life murder of Hazel Drew.

This happened all the way back in 1908, in a little town in New York State called Sand Lake. Hazel Drew was a 20-year-old woman who disappeared on the night of July 7, with her body washing ashore on the banks of the local pond four days later. She had a corset string around her neck and a head injury from a blunt object. Plus, there was no water in her lungs, indicating that she was dead before going into the pond.

The details surrounding the investigation were very reminiscent of Twin Peaks. The list of suspects included a “dim-witted farm boy,” a “peddler of charcoal,” a dentist named Edwin Knauff who was in love with the victim, and even a man who was said to possess hypnotic powers. There was also some sordid gossip which alleged that Hazel Drew led a double life by taking part in orgies with older businessmen.

Modern sleuths who combed through the documents and newspaper reports from that time suggest that the local authorities were keen to dismiss the notion that there was a murderer in their little town. Instead, they put forward the idea that Hazel Drew had been run over by a reckless driver who then tried to get rid of the body by dumping it in the pond. While not impossible, it was inconsistent with the victim’s injuries, and the Teal Pond Mystery, as it came to be known, remains unsolved.