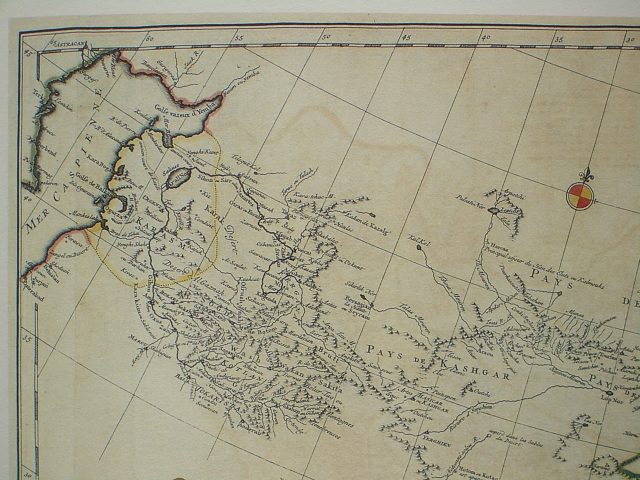

From Austria to Japan, from Eastern Turkey to Vietnam. These were the borders of the largest contiguous empire in human history. Nine million square miles it stretched, much more than double the size of the modern United States of America. Its rise began in 1206 and its fall finished in 1368, a blip compared to the historical longevity of such nations as the Chinese Empire that the Mongols caused so much turmoil.

A continent doesn’t experience that much change without many amazing things happening, for better or worse. Generally for worse, since we’re talking about the subjugation of tens of millions of people under force of arms. Not for nothing did the most celebrated Mongol leader Genghis Khan tell his enemies that he was the “Flail of God.” So let’s take a tour of those 162 years, with 10 stops along the way.

10. Changing the Climate

It’s hard to get reliable figures for how many people died across Asia and Europe, as the Mongols under Genghis Khan exaggerated the number of people they killed. Still, there is general scholarly agreement that when the Mongols sacked a city, it was possible they killed as many as 2,000,000 people as was the case with the sack of Baghdad in 1258, and that was one of very many. Consequently, the Mongols left so many corpses in their wake that they cut down the need for fires, and cut down trees to such an extent across much of Asia that they functioned as a carbon offset. Not even the Black Death of the 1300s did that, and that cost more than 25,000,000 lives.

The study that reached this conclusion was conducted in 2011 as part of the Carnegie Institution Department with Stanford University. They found that over the course of the Mongol Invasions of the 1200s, 700,000,000 tons of carbon was not released into the atmosphere. This would not have produced any obvious change, as that’s about how much the world currently emits into the atmosphere through gasoline alone every year, spread out over decades. Populations also recovered before any of the old forests could have completely regrown so the effect was not lasting. Still, given that Genghis Khan claimed he was the representative of the “Eternal Blue Sky,” it seems that by changing the weather itself in a sense he lived up to his name.

9. The Family of Creepy Births

It was not unknown for later histories to write legends around the births and childhoods of momentous figures. For example, the story of Romulus and Remus being somehow raised by a wolf is well known. There’s also the legend that the Temple of Artemis in Greece burned down the day Alexander the Great was born. But the 1162 birth of Temujin/Genghis Khan must be one of the grimmest. According to Mongolian accounts, Temujin’s mother Hoelun told him that he was born holding a clot of blood in his hand, which was held up as a sign that he was destined to be a great conqueror.

Less well publicized but equally unnerving is what Hoelun said that Temujin’s brother Khasar did when he was born. Supposedly he had entered the world “gnawing like a dog on (his) own afterbirth.” It must be said that Hoelun was alleged to have said this after she learned that Temujin and Khasar had both murdered their brother Begter with arrows, so the source had plenty of reason to speak ill of Khasar. Despite this, when Temujin was going to put Khasar to death after he had risen to command of the Mongols, it was Hoelun who intervened to persuade Temujin to not shed the blood of a second brother. Temujin thereafter gave Khasar a token command of about 1,400 troops, showing Mongols that apparently being born mouthing your own afterbirth was not nearly so great an omen as holding a blood clot.

8. Near Invasion of Continental Europe

The nations that felt the full wrath of Mongol conquest included China, Russia, Korea, Khwarezima (modern day Iran). Austria nearly joined that list too, and with the loss of Vienna much of Western Europe would have been vulnerable to conquest or at least devastating raids by Mongol hordes. The Mongols gave two very compelling examples of how they would manage against any armies the European nations threw at them.

On April 9, 1241 an army of 20,000 Mongols confronted an army of 30,000 at the Battle of Legnica in Poland under Duke Henry. The Mongols drew out Henry’s cavalry with a feigned retreat, then through a heavy bombardment of rockets created a smokescreen that cut off contact between the European cavalry and infantry. When the cavalry was routed, they switched their bombardment to the European footmen with devastating effect until they broke as well. It was said that the heavily outnumbered Mongols practically annihilated their foes, and were able to cap off the victory by parading Duke Henry’s head.

The very next day, 100,000 Europeans under King Bela IV faced 80,000 Mongols under Batu Khan and Subedi at Sajo River in Hungary. The Mongols were able to both frontally attack and come up from behind the European army in a pincer movement, resulting in a rout of the Europeans under heavy flaming catapult fire. The results were better only to the extent that the European army wasn’t completely destroyed, but even the lower estimates for losses put them at 60,000 dead.

So what saved Europe from Mongol hordes before which their armies melted like snow? Pure luck: That same year, Ogedai Khan died and the armies retreated to mourn his passing before they could fully take advantage of their victories. Ogedai Khan was recorded as being a particularly intelligent and lenient Khan, but as far as European history is concerned by far the most significant aspect of his personality was how his great love of wine put him in an early grave.

7. Engineering Marvels

Although the Mongols owed the majority of their astoundingly fast imperial expansion to their exemplary horse archers, Genghis Khan’s nomadic upbringing had taught him to appreciate the benefits of alliances and arrangements with outsiders possessing special goods and skills. So in 1214, eight years after Genghis Khan had taken control of the Mongols, the Mongols had created a corps of engineers to break them into enemy cities, a group which began with 500 soldiers and grew into miracle workers.

For example, at the Amu Daryu River the engineers under Master Zhang were able to whip up a bridge in record time by lashing together 100 ships. For the sack of Baghdad mentioned in entry 10, the engineers redirected the Euphrates River so that the waters flooded their enemies and disrupted their defenses. Mongol trebuchets would fire so many missiles at encampments that they often depleted the number of large rocks available, and other boulders had to be hauled across the empire. With such a heavy workload, the Mongols sensibly adopted a policy of sparing any engineer when they sacked a city.

6. Mongols as Attempted Peacemakers

Even knowing that the Mongols had a sophisticated military machine and tactics, the main impression we have of them is as a bunch of bloodthirsty warmongers. The relationship with Khwarezmia is all the more surprising, then, because Genghis Khan reached out to them only as a potential trade partner. Even the Persian historian Juzjani agreed that was the nature of the arrangement, and as we’ll see, he would have good reason to portray the Mongols in a negative light.

It went south in 1219 when a caravan of Mongols was massacred in the city of Ortar. But the Mongols still didn’t rush into war. When Khan sent diplomats to demand something be done about this, Shah Muhammad responded by sending back the corpses of Khan’s messengers. It was only then that Genghis Khan decided to become the Flail of God for the Islamic nation and leave millions dead.

5. Planting the Seeds for the Viet Cong

While for decades the mightiest empires of Asia were unable to stop the Mongols, a modest nation in Southeast Asia was able to stand strong. In 1283, two years after the final Mongol attempt to conquer Japan had ended in disaster, Kublai Khan sent a seemingly overwhelming army down into the Red River Valley in what is now Vietnam. After all, the Khan a military victory somewhere to save face. Unfortunately for the Mongols, the people of Vietnam had a leader named Tran Huang Do who was able to rally them to take a stand against the largest empire in the world, which had defeated massive opponents in battle.

What allowed the Vietnamese people to succeed where so many other nations had failed was their refusal to fight large, pitched battles against the horde. They allowed the Mongols to take their capital, but they had been fighting using scorched earth and guerrilla tactics until the Mongol lack of supplies (jungles and mountains are bad for grazing horses) forced them to withdraw.

More determined than ever to save face, Kublai Khan sent another invasion in 1287. This time the Vietnamese turned to naval cleverness. The Mongols sent their navy to the Bach Dang River, and the Vietnamese were able to lure their ships onto great iron spikes that they had placed beneath the waters. Tran Huang Do’s methods were so successful that for centuries they were the model used by the Vietnamese against invader after invader, most famously by the Viet Cong against the French and American militaries.

4. Regulatory Capitalists

Although the Mongol culture that Genghis Khan took control of was nomadic and its soldiers were willing to show little quarter, they understood the need for trading. They were much more inclined to hunting and horse archery than they were such labor as fletching, so good relations with merchants were key even when the Mongols were just another isolated community on the steppes. The Khans made sure they remained vitally important even after their empire reached its zenith.

The Chinese and Persian empires had not been nearly so respectful of merchants, and taxed them heavily. Under the Mongols taxes were lifted on merchants, and Mongol troops were devoted to protecting them. As a result the Mongol Empire was flooded with merchants, aided in their travels by the elaborate road system that the Mongols built, mostly famously with the Silk Road. Merchants were even allowed to use government postal/relay stations. This was eventually taken away because the privilege was being abused. Even empires that are willing to destroy cities with millions of people in them will only put up with so much uncouth behavior.

3. The Christian Challenge

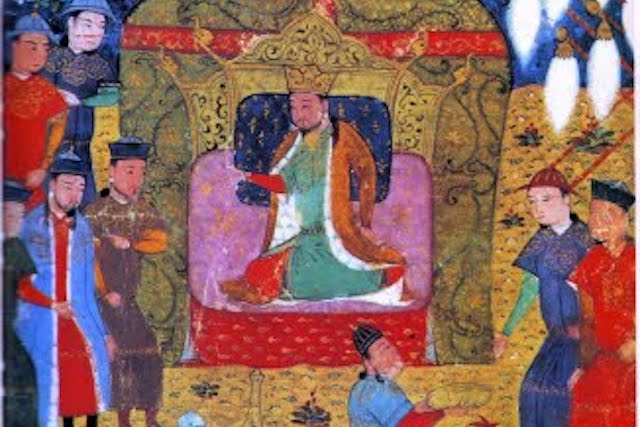

When Genghis Khan said that he represented the “Eternal Blue Sky,” he wasn’t idly boasting. The Mongol conquests were to a significant degree a religious crusade. So it’s especially surprising that in the wake of their stunning success, which you’d imagine would be extremely validating to their religious doctrine, the Mongols largely turned to other belief systems. Kublai Khan for one turned to Buddhism in 1242. But Kublai seemingly wasn’t even particularly adherent to that religion, and presented a truly stupefying religious offer after he had taken the throne.

In 1266, nine years before the famous arrival of Marco Polo, Kublai had a message sent to the Pope. If 100 clergymen, or “men skilled in your religion” as he put it, were sent to his royal palace, and if they convinced him, he would have himself, his court, and all his subjects to be baptized. “There will be more Christians here than there are in your parts,” as he put it, most likely accurately.

Almost as surprising as the Khan’s staggeringly generous offer was the pope’s halfhearted answer. Accounts vary on just how many clergymen were sent, some saying two while others go as high as seven. By all accounts it was well under the requested 100, but even if it had been 1,000 the opportunity slipped through the church’s fingers because they arrived too late for the Khan to receive them. To be fair, considering that the Mongols had destroyed European armies just two decades earlier, it would be understandable for the Pope to be skeptical.

2. Strong Social Welfare Programs

You’d think since they emerged from a nomadic lifestyle fraught with hardship and violence, the Mongols would be harsh and austere with their subjects. That certainly wasn’t the case for Kublai Khan. There were programs for even the poorest of the Mongol Empire.

Kublai Khan greatly expanded the empire’s crop yields by creating an Office for Stimulation of Agriculture. To prepare for inevitable bad harvests, he had immense granary systems built, including 58 in the capital city of Beijing. He was not stingy with the reserve grain either. According to Marco Polo, everyday meals were provided for roughly 30,000 impoverished people in Beijing. Whether it was out of genuine compassion for the people or to maintain order, the effect was the same.

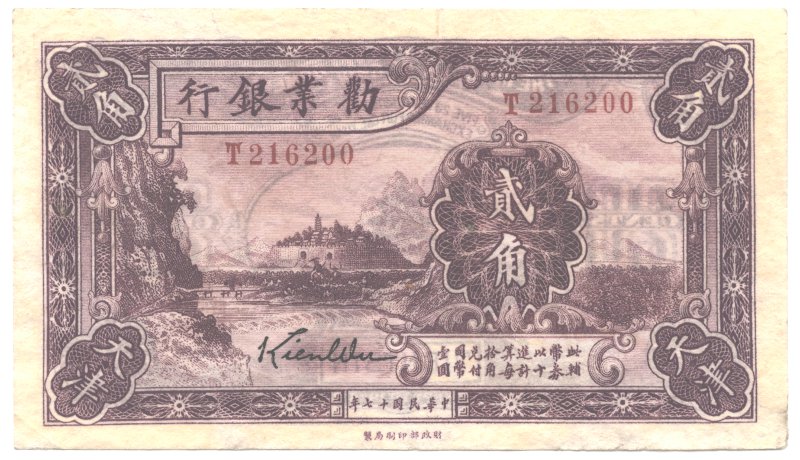

1. Hyperinflation

We don’t want to give the impression that Kublai Khan’s time as Emperor was a complete domestic success. Even with such issues as enemies across continents and ambitious rivals for the throne that were willing to plunge the empire into civil war time and again, historians maintain that what brought down the empire was a venture that was relatively harmless on paper. In fact, it was something that quite literally was on paper that massively contributed to their fall.

Paper money was by no means invented by the Mongols, and in fact the Song region of China had introduced it nine years before the Mongols conquered them. Still, they brought it back and spread it across the empire, calling it “chao” in China and “djaou” in Persia. The Mongols made the classic mistake of not backing their printed money with any supply of precious metal or any other commodity, and thus as the cost of failed wars mounted they tried just printing more and more money. The burden of currency that became effectively worthless was too much to bear for their peasants, and the seeds of revolution were sown. Even the cleverest, most accomplished warrior nation was no match for the ravages of fiat currency.

Dustin Koski can be followed on Twitter.