For seven centuries, samurai represented the fearsome military branch of the Japanese aristocracy. Trained and taught from a young age, they became formidable warriors in service of their lord or daimyo. They were some of the best swordsmen that the world had ever seen and were renowned for the code of honor that they adhered to… for the most part.

Some samurai could grow to be very powerful and become daimyo themselves, then finding their own samurai to take on as retainers. Some of them even became shogun, the mighty dictators who ruled over the country. With such a long and varied history, we could never fully cover the extent of their deeds in just one video, but we are going to take a look at some of the most notorious samurai to ever swing a katana.

8. Miyamoto Musashi

We start off this list with the man many consider to be the greatest samurai swordsman in history – Miyamoto Musashi. Born around 1584, he was the son of a master martial artist named Shinmen Munisai and, unsurprisingly, started training at an early age.

According to Musashi himself, his first duel came when he was just 13 years old, when he killed a much more experienced samurai named Arima Kihei. This was one of over 60 individual sword fights that Musashi participated over the course of his career. He won all of them, fighting many of his opponents to the death.

For much of his life, Musashi was actually a ronin, meaning a samurai without a master. That was because his father’s clan, the Shinmen, fought on the losing side of the war between the Toyotomi and Tokugawa clans. On October 21, 1600, the Battle of Sekigahara ended in a decisive victory for the latter and brought on the Tokugawa shogunate. Musashi’s exact role in this epic battle is somewhat unclear, but afterwards he seemingly disappeared from the records for a few years.

Musashi traveled throughout Japan in order to hone his skills as a warrior. His most famous duel was against another master samurai named Sasaki Kojiro. This notorious fight has been heavily mythologized so it’s hard to pinpoint any accurate details. Kojiro was known for using a very long sword called a nodachi, while Musashi allegedly defeated and killed him using a training wooden sword called a bokken which he carved out of an oar while traveling to the location of the duel.

Musashi settled down during the 1630s and was taken as a retainer by the Hosokawa clan. He cemented his legacy as a master swordsman by writing down his teachings in Go Rin no Sho, or The Book of Five Rings.

By the way, Miyamoto Musashi’s life was far too eventful to fully cover in this entry but, if you want to learn more, we already did a full-length video on him on our sister channel, Biographics, you can check it out there.

7. Kusunoki Masashige

Samurai were renowned for their code of honor and the unwavering loyalty they showed to their lords. Perhaps this was best illustrated by Kusunoki Masashige, a 14th century samurai who is today regarded in Japan as a patriotic symbol called Dai-Nanko.

A retainer of Emperor Go-Daigo, little is known about Kusunoki before he started rising through the ranks in the emperor’s employ. He was active during the Genko War, an attempt by the emperor to seize power from the Kamakura shogunate. He was eventually successful in 1333, starting the Kenmu Restoration.

This period was short-lived, though, only lasting for three years. Go-Daigo was betrayed by one of his generals, Ashikaga Takauji, who saw an opportunity to start his own shogunate. He raised arms against his former master and pushed him back successfully all the way to the capital of Kyoto.

With their backs against the wall, Kusunoki suggested to the emperor to abandon Kyoto and regroup in the mountains. Go-Daigo refused to leave the capital, however, insisting that his loyal samurai faced Takauji in pitched battle. Kusunoki proposed several strategic options, but they all fell on deaf ears. This was basically a suicide mission as the enemy forces were superior in every way, but Kusunoki was undeterred. He took his army and fought bravely, but was quickly overwhelmed and perished in battle.

His legacy was carried on by his son, Kusunoki Masatsura, who became a venerated samurai in his own right. He loyally served the next emperor, Go-Murakami, until he also died in the Battle of Sakainoura in 1348.

6. Akechi Mitsuhide

We learned about a samurai famed for his loyalty, so how about one infamous for his betrayal? In fact, Akechi Mitsuhide might be the most notorious samurai traitor in history as his double-crossing had a significant impact on Japan.

Also called Jubei, Akechi was born in 1528 as part of the Toki clan. As a samurai, he ended up in the service of a young daimyo named Oda Nobunaga and, eventually, became one of his vassals.

Nobunaga had grand ambitions of unifying Japan and he succeeded…mostly. It was, in fact, his retainers, Toyotomi Hideyoshi and Tokugawa Ieyasu, who finished his work and, together, they became remembered as the Three Unifiers, ushering in a new chapter in Japanese history.

Through conquest, Oda brought most of Honshu under his control, but it was not his rivals who caused his downfall, it was one of his own samurai. In June, 1582, Oda traveled to Kyoto to meet with his son, Oda Nobutada. They held a tea ceremony at Honno-ji Temple but, unbeknownst to them, Akechi was heading their way with an army. Nobunaga only had a small retinue with him and they were quickly overwhelmed. With no chance of escape, Oda Nobunaga committed suicide. In some versions, he also had the temple burned down so that his enemies could not get his head.

The exact reasons for Akechi’s treachery still remain a mystery.

5. The 47 Ronin

Okay, it might be cheating a little bit to include 47 men in one entry, but the story of the 47 ronin, or the Ako incident, as it is sometimes called, is one of Japan’s most legendary tales that has to be mentioned whenever discussing samurai.

It all started in 1701 when a minor daimyo named Asano Naganori hosted an important official of the emperor named Kira Yoshinaka. We’re not sure on the circumstances – some sources say Kira was very rude and arrogant, others that he demanded a bribe. Eventually, the honorable Asano could not take it anymore and attacked the official, injuring him with a dagger. For this, Asano was forced to commit suicide by seppuku, while his lands were confiscated and his samurai turned into ronin.

Forty-seven of Asano’s most loyal retainers began plotting their revenge. However, they realized that Kira would expect samurai to feel duty-bound to avenge their master so they had to convince him to lower his guard.

For two years, the 47 ronin found new jobs as workmen. Some became monks. Their leader, Oishi Kuranosuke, knowing that he had spies following him, even left his family and became a homeless drunkard to persuade everyone that he was a coward without honor and had no interest in revenge.

Their plan worked. Eventually, Kira thought that he was safe. On the night of January 30, 1703, the 47 ronin gathered together, armed themselves and broke into his mansion. They easily bested Kira’s small group of bodyguards. According to the most popular version of the story, they gave the official the chance to die with honor by committing seppuku with the same knife as their master. He, however, refused and still begged for mercy so one of the samurai cut off his head.

One of the ronin acted as messenger and went to tell the news to Asano’s family. The others brought the head to the tomb of their master and then turned themselves in. They were allowed to commit seppuku.

4. Tomoe Gozen

Generally, the violent world of the samurai was restricted to men, but not exclusively. There were also female samurai warriors called onna-bugeisha who were part of the same noble class as their male counterparts and trained to fight from a young age, preferring the naginata polearm to the more traditional samurai sword.

These female warriors were far more common during the earlier centuries of feudal Japan and it wasn’t unheard of for onna-bugeisha to rise to the rank of general in their masters’ armies.

One prominent example was Tomoe Gozen who served the Minamoto clan during the 12th century. Her master was Minamoto no Yoshinaka, who feuded with the Taira clan during the Genpei War. This event was immortalized 150 years later in an epic narrative called The Tale of the Heike where Tomoe is described as a woman of incredible beauty who was also a proficient archer, horserider, and swordsman. Tomoe was also Yoshinaka’s most trusted samurai as he always sent her out first in battle because “she performed more deeds of valor than any of his other warriors.”

With Tomoe’s help, Yoshinaka defeated the Taira clan, but then war erupted between him and his cousin and the Minamoto clan split into factions. Yoshinaka was defeated at the Battle of Awazu in 1184, but Tomoe slain the samurai Uchida Ieyoshi who was sent to capture her.

The same account gives us the end to that battle, when only five survivors remained of Yoshinaka’s army. Knowing death was inevitable, the clan leader sent Tomoe away because she was a woman. Instead, she charged alone into a group of 30 enemies led by a samurai named Onda no Hachiro Moroshige of Musashi. She grappled with him, threw him off his horse, jumped down and cut off his head. Only then did she take off her armor and flee the battlefield.

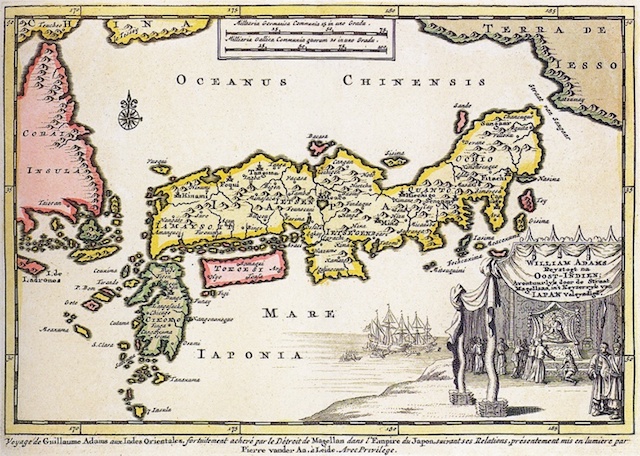

3. William Adams

Now we move on to another special category – that of foreign samurai. Debates whether William Adams could truly be considered a true samurai or not are still ongoing, but his story is truly a famous one as it formed the basis for the iconic novel Shogun by James Clavell.

Adams was a navigator aboard a five-ship Dutch trading expedition. It was a rather disastrous mission and, after over a year-and-a-half at sea, only one ship reached Japan. The roughly two dozen sickly men aboard were arrested and imprisoned by a daimyo named Tokugawa Ieyasu who we already mentioned as one of Japan’s Three Unifiers.

Adams had several things that worked in his favor. For starters, it was great timing. His arrival took place just a few months before the landmark Battle of Sekigahara in 1600 when Ieyasu became the uncontested ruler of Japan as the first shogun of the Tokugawa shogunate. The other ace up his sleeve was his knowledge of shipbuilding, navigation, engineering, and mathematics, all which greatly interested the new shogun, as well as fascinating tales from the outside world. Slowly, but surely, Adams’ role increased at Ieyasu’s court.

Even so, the Englishman had a wife and daughter back home and, inevitably, he wanted to leave Japan. This was unacceptable to Ieyasu who forbade it. However, instead of punishing Adams, he tried to make it so the English sailor would never want to leave by bestowing upon him honors never before given to a foreigner. He gave him a lordship and a country estate complete with retainers to serve him and serfs to work his fields. Adams was named a hatamoto, a title given to the most loyal samurai retainers in direct service of the Tokugawa shogun. He was also allowed to carry two swords, again an honor only reserved for samurai.

Adams was not a battle-hardened warrior. He never fought for his daimyo which is why some people don’t regard him as a true samurai. However, his services were clearly valuable enough that the shogun elevated him as equal to his most prized warriors.

2. Honda Tadakatsu

Speaking of those warriors, perhaps none were more prized than Honda Tadakatsu who was instrumental in helping his lord form the Tokugawa shogunate.

Tadakatsu was right in the thick of it as Ieyasu worked under Oda Nobunaga to either submit or destroy the other clans and unite them all under one leadership. He was there in 1570 at the Battle of Anegawa when Ieyasu and Nobunaga first fought together and was there in the end when Ieyasu triumphed, formed a new shogunate and launched Japan into the Edo period.

During his decades of service, Honda Tadakatsu became part of the Four Heavenly Kings, a sobriquet used to describe Tokugawa’s most trusted generals. He was also called “the warrior who surpassed Death itself” because, according to legend, Honda was involved in over 100 battles but never sustained a serious injury.

In combat, Tadakatsu was known for his unique helmet which was adorned with large antler deers so that his enemies always knew who they were fighting. His most glorious moment in battle came during the Komaki Campaign in 1584 and did not actually involve any combat whatsoever.

His master, Tokugawa Ieyasu, had left Komaki with his army. Tadakatsu and a small group stayed behind, but saw that a giant enemy force led by their daimyo, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, was in pursuit of Ieyasu. Honda gathered the men he had at his disposal and immediately rode out to meet them in combat, hoping that he could delay the enemy long enough so that his master could escape.

This was clearly a suicide mission as they were outnumbered dozens of times over. As Honda put it, they had to “sell [their] lives as dearly as possible, for every hour…is precious to [their] lord.”

Hideyoshi saw the small force trying to engage him in combat across a river and realized instantly what their intent was. He commended Honda for his bravery, noting that he wanted “to help his lord at any sacrifice.” The daimyo gave the order to leave Honda and his riders alone because, should he win the war, he would need such men in the future.

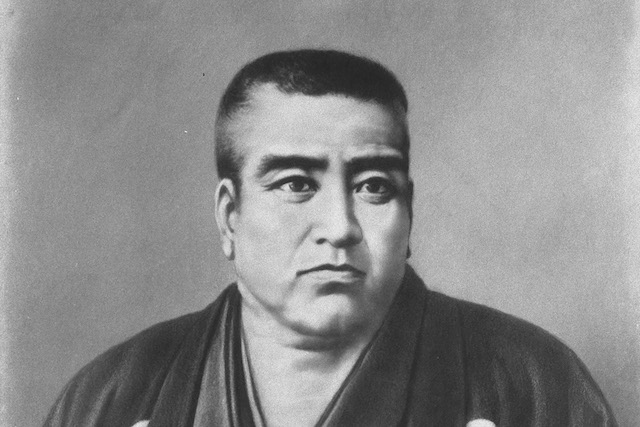

1. Saigo Takamori

In the minds of many, a samurai will always be a medieval warrior of supreme skill, clad in armor and wielding a katana on the battlefield. But the reality is that samurai were around until the late 19th century when they began being abolished. They were a remnant of the obsolete feudal system and were slowly integrated into modern Japanese society while taking away the privileges they enjoyed for centuries such as receiving guaranteed stipends and being able to execute commoners without repercussion.

This was a consequence of the Meiji Restoration, a major moment in Japanese history which marked the end of the shogunate system which had dominated the country for most of the last 700 years. Obviously, samurai were against this as they knew the end of the shogunate meant the end of the samurai. However, there were a few who went against this thinking; who realized that the old ways were antiquated and would have to go in order for Japan to be able to compete not only with its neighbors, but with the western powers which were far more advanced technologically and had superior armies. One of these men was Saigo Takamori, dubbed “the last samurai.”

In Japan, Saigo is remembered as one of the Three Great Nobles of the Restoration for the vital role he played. His early life was indicative of the changing times. Although his father was a minor-level samurai and he, too, received samurai training, Saig? worked as a bureaucrat, not as a warrior, mostly dealing with agricultural projects. Even so, during the Boshin War between the shogunate and the pro-imperial forces, Saigo showed himself to be a capable and compassionate leader who looked for a bloodless solution wherever possible.

The samurai was made an army general under the rule of the emperor, but he resigned due to disagreements with other officials over whether Japan should go to war against Korea or not. Meanwhile, the country was still full of small rebellions of samurai who were angry at the loss of their many traditions and privileges. Albeit reluctantly, Saigo led one such revolt in 1877 against the very government he fought to install. It lasted less than a year until it ended decisively following Saigo’s death at the Battle of Shiroyama.

Saigo was a man stuck between two worlds, not being able to completely accept either of them. Despite dying a rebel, he remained popular with the people due to his embodiment of the traditional values they ascribed to samurai who had become a dying breed. Because of this, he was pardoned by the government 12 years later and officially remembered as one of the heroes of the Meiji Restoration and Japan’s last true samurai.