There are many terrifying places in the world, but few of the horrors that they contain are as scary as radiation. When a site becomes thoroughly nuclear, you can’t fight it, you can’t outrun it, and you’re pretty hard-pressed to contain it. No matter how well the location is cleaned and taken care of, the residual radiation can still affect the environment for hundreds of years. There are many of these extremely creepy and dangerous sites around the world. These are their stories.

10. The Polygon

When the Soviet Union crumbled and Kazakhstan became independent, one of the first things they did was shutting down The Polygon. This Soviet nuclear testing site had seen tryout nukes of various sizes for over four decades, and during its Cold War heyday, it was home to an estimated 25% of the world’s nuclear tests. The site was originally chosen because it was unoccupied, but this didn’t take into account the many villages that were located near its perimeter. Years of nuclear radiation bombarded the area, and eventually, the residents of the “safe” villages started showing birth defects and various radiation-related illnesses.

Today, it is estimated that at least 100,000 Kazakhs near the Polygon area suffer from the effects of radiation. The radioactive materials at the Polygon itself will take hundreds of years to reach safe radiation levels, and the poor people suffering from the effects may do so for five generations.

9. Chernobyl

It’s impossible to discuss radioactive sites without bringing up Chernobyl. The 1986 nuclear power plant explosion in Ukraine is considered the worst nuclear disaster that the world has ever witnessed, and despite the fact that it’s been extensively researched, many questions remain. The most pressing of those questions concern the long-term health impacts of the people who were exposed to the radiation. Acute radiation sickness wreaked havoc among the first responders to the scene, but that was just the tip of the deadly iceberg: The nearby town of Pripyat was not evacuated until 36 hours after the disaster, and at that point, many residents were already showing symptoms of radiation sickness. Despite all these clear signs that the situation was pressing, and the realization that the disaster sent nuclear winds blowing towards Belarus and into Europe, the Soviets still tried to play the situation close to their chest — right up until the radiation alarms at a nuclear plant all the way in Sweden went off, and the terrifying situation unfolded.

On the surface, Chernobyl’s death toll was surprisingly moderate: “only” 31 people died in the disaster and its short-term aftereffects, and the Still, the long-term effects to the people in the area were still unsafely high, though just how the disaster affected their lifespans is very difficult to measure. For instance, an estimated 6,000 cases of thyroid cancer in Ukraine, Russia and Belarus may be connected radiation exposure in some way, but it’s borderline impossible to directly link them to the disaster.

8. Siberian Chemical Combine Plant

Siberian Chemical Combine (SCC) is an old uranium enrichment plant in, yes, Siberia. When it comes to its waste disposal, it was always a product of the patented Soviet “eh, just put it wherever, comrade” way of doing things: Significant amounts of the combine’s liquid radioactive waste were pumped into underground pools of water. That would probably been bad enough even without the nuclear accident of 1993, which saw an explosion damage the radio-technology plant of the complex. The blast wrecked two floors of the building, and more importantly, destroyed a tank containing highly dangerous materials such as plutonium and uranium.

The radioactive gas released by the incident contaminated 77 square miles of downwind terrain, and only sheer luck prevented the fumes from turning the nearby cities of Tomsk and Seversk into Fallout locations. The cleanup process took four months, but for locals, the disaster was just the beginning of the nightmare: They found out that there had been a whopping 22 accidents at the SCC over the years, and even during its normal operations it released around 10 grams of plutonium into the atmosphere every year. For reference, it takes just one millionth of a gram to potentially cause serious diseases on humans.

7. Sellafield

Sellafield is to Great Britain what Chernobyl is to Russia: The worst ever nuclear accident to happen in the country. In a way, it managed to be even more badly managed than its more famous counterpart — or rather, managed in a more British way. When the Windscale No. 1 “pile” (a sort of primitive nuclear reactor) of the Sellafield nuclear material processing factory caught fire in October 1957, eleven tons of uranium burned for three days. Despite this rather worrying situation, everyone went about their day as if nothing had happened. While the reactor was close to collapse and radioactive material spread across the nearby areas, no one was evacuated, and work went on in the facility with a stiff upper lip. In fact, most people weren’t even told about the fire. The workers realized that something was going on, but were told to “carry on as normal.”

Meanwhile, a true disaster was just barely averted, largely thanks to one heroic man. When the fire started, deputy general manager Thomas Tuohy was called on site from a day off. When it came apparent that the blaze could not be easily contained, he threw away his radiation-recording badge so no one could see the doses he was taking. Then, he climbed at the top of the 80-foot reactor building, and stared at the inferno below him while taking the full force of the radiation. He did this multiple times over the next hours to assess the damage, and when the blaze started to reach the melting point of steel, he made the last-ditch call to use water to drown the pile. It was a risky maneuver that was untested on a reactor fire, and if anything had gone wrong, the whole area would have been blown up and irradiated to the point of uninhabitability. Fortunately, Tuohy’s gambit paid off, and 30 hours of waterworks later, Sellafield was saved. While the area was thoroughly irradiated all the way down to its milk and chickens, Britain carried on with a stiff upper lip. Of course, Tuohy himself, who had basically wrestled with the burning reactor, eventually died … at a respectable age of 90.

6. The Somali Coast

The coastal areas of Somalia are better known for their pirate activity than their nuclear materials, but that’s just because the radioactive waste tends to be hidden under the surface. Weirdly enough, the two phenomena have the same cause: The area’s unrest during the 1980s led to a long period where the country had no central rule, which left its shores unguarded. Unfortunately for Somalia’s residents, this meant that every unscrupulous operator and their mother was free to cheaply dump their unwanted nuclear and other hazardous waste along the country’s coastline, instead of disposing of it in a safer (and much more expensive) manner.

The United Nations have been aware of the problem for years, and describe it as a very serious situation. It was further aggravated in 2009, when a large tsunami made the problem literally resurface. The wave dislodged and broke many of the containers, causing contaminants to spread at least six miles inland. The cocktail of radioactive materials and assorted toxic sludges caused a host of serious health problems for the residents, and may even have contaminated some of the groundwater.

5. Mayak

Even before Chernobyl, there were whispers that the Soviet Union’s track record with nuclear power wasn’t exactly spotless. Some of said whispers were almost certainly about the Mayak complex, which was the country’s first nuclear site. Built in the remote southern Urals shortly after WWII, Mayak was a secret military site that was near the closed town of Chelyabinsk, and specialized in manufacturing plutonium for the army. Its secretive nature eventually came in handy for the Soviet government.

In 1957, the complex suffered one of the worst little-known nuclear disasters, when an accident at the facility contaminated 7,700 square miles of the nearby area, which affected roughly 270,000 people. The incident would eventually become known as the Kysthym disaster, after the nearest town. At the time, however, the authorities fully played the “secret facility” card, and released little information about the crisis. The true scale of the disaster would not emerge until the Soviet Union collapsed in the 1990s. It took until 2009 for the villagers nearest to the Mayak facility to be relocated … and even then, most of them were just moved a little over a mile up the road.

4. Church Rock uranium mill

In 1979, a spill at the Church Rock uranium mill in New Mexico sent 1,100 tons of uranium mine tailings and 94 million gallons of effluent into the Puerco River, spreading contamination some 50 miles downstream. Together, these released three times more radiation than the notorious Three Mile Island nuclear accident.

To this day, the Church Rock spill remains the largest accidental release of radioactive material the United States has ever seen, and its damage to the environment was wholesale. Radioactivity was in water, animals, plants and, eventually, the Navajo population of the area, who suffer from an increased likelihood of birth defects and kidney disease.

The disaster is particularly tragic because it would have been perfectly avoidable. The spill happened because one of the dams holding the United Nuclear Corporation’s disposal ponds at bay cracked. Later, both the corporation itself and various federal and state inspectors noted that the rock it had been built on was unstable.

3. Fukushima

In March 11, 2011, the Great East Japan Earthquake moved the entire Japan several feet east, and sent tsunami waves washing over the country’s shorelines, causing a death toll of 19,000 people … and the worst nuclear plant disaster in the country’s history. Initially, it seemed that the Fukushima Daiichi power plant had withstood the watery onslaught, and that all of its reactors had automatically shut down and survived without significant damage. However, the plant was not quite as tsunami-proof as everyone had assumed, and it soon became evident that the wave had disabled the cooling systems and power supply for three of the reactors. Within three days, their cores had largely melted, and a fourth reactor started showing signs of trouble.

The government evacuated roughly 100,000 people from the area, and engaged in a battle to cool the reactors with water — and even more importantly, to prevent radioactive materials leaking in the environment. Since the facility is just 100 yards from the ocean and on an area that’s prone to various natural disasters, the cleanup process is a difficult, yet urgent task. The radiation inside the plant is so deadly that it’s impossible to enter the facility, so no one’s even sure precisely where the molten fuel is within the plant. In a massive, unprecedented challenge that is estimated to take decades, the cleanup officials are currently mapping the terrain with radiation-measuring robots, and hope that strong robots are eventually able to seal and retrieve the radioactive substances from the premises.

2. Mailuu-Suu

Mailuu-Suu is a town in Kyrgyztan that not only lives under the constant shadow of Soviet-era radiation, but has actually made its peace with the fact. Some locals joke that they actually need the radiation to survive. You can even get walking tours to the worst radioactive waste dumps — followed by a healthy dose of vodka to flush the radioactivity out of your system, of course.

The town is one of the largest concentrations of radioactive materials in former Soviet Central Asia. Because the area is naturally rich in uranium, the Soviet Union mined it to death, while toxic waste was buried all around town. All in all, some two million cubic meters of radioactive waste lies under gravel and concrete, in 23 different dumping sites around Mailu Suu. The sites are often just lazy piles of hazardous material lying in their deteriorating bunker pits, halfheartedly marked with barbed wire and concrete posts.

Unfortunately, this makes Mailu Suu both a current crisis and a future, potentially much worse one. The dumping sites are located right by a fast-moving water source, the Mailuu-suu river, which is a water supply for two million people downstream. What’s more, the area is tectonically active, and extremely prone to landslides. This has already led to one nasty disaster: In 1992, one of said landslides busted one of the waste dumps open … and 1,000 cubic meters of radioactivity spilled into the river.

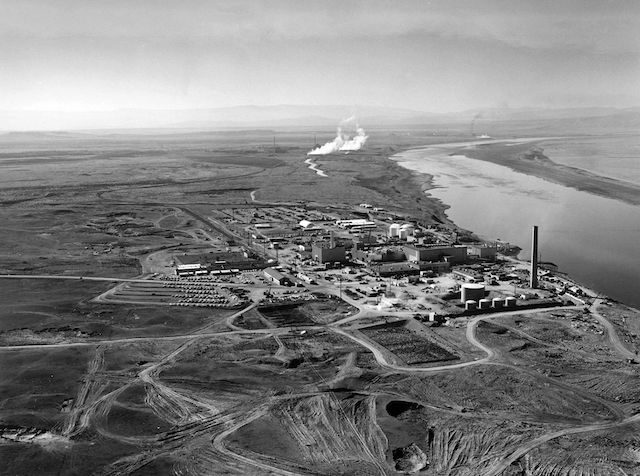

1. The Hanford Site

In the 1950s, America was happily entering the Atomic Age, and the nuclear site in Hanford, Washington was where the future was made. The plant had already made its mark in the 1940s during the Manhattan Project, for which it was built to produced the plutonium required for the nukes. After the war, the future seemed bright in more than one way. Although every kilogram of plutonium the site produced came with a side order of hundreds of thousands of gallons of radioactive waste, the site’s entrepreneuring owners believed they could sell even that. Unfortunately, they couldn’t … and they also hadn’t bothered to create proper ways to store the deadly sludge.

As years went by, temporary underground containers quietly became permanent, cracked, and allowed their radioactive contents to seep in the ground. The Atomic Energy Commission, which oversaw the manufacture of nuclear bombs, didn’t even bother to set up an office for waste management, so unregulated radioactive material ended up buried wherever, in containers that creaked at the seams. In the end, Hanford and its nearby areas were so saturated with radioactive waste and strange toxic sludges that the site became the largest nuclear cleanup site in the entire western hemisphere. The cleanup process has gone on for decades, caused health problems to dozens of workers, and cost billions of dollars, but the treatment plant that’s meant to deal with the sludge is yet to materialize. In fact, the area is still so deeply dangerous that when they started to demolish the site’s plutonium finishing plant in 2017, 42 workers became exposed to radioactive particles despite all the precautions.