Many Americans are trying to keep the “Manifest Destiny” and “Great Person” theories of US history going. They want the United States of America’s creation to have been some result of divine forces so that more people treat it with fervor, if not reverence. This view of American history is especially desirable when issues such as reparations are being discussed.

The truth of American history is that a lot of the most significant events were essentially mad men grasping wildly. Most creators of history curriculums don’t want to admit that, so the historical periods where they had the most influence are often glossed over in lessons, such as the majority of US history between the US Civil War and World War I. Even when the historical periods where they were influential are put in the educational spotlight, these figures have been pushed to the side. Well it’s time to shift that light a little and show that US history was a crazier, less predictable place than we might have thought.

10. The Van Sweringen Brothers

Born in 1879 and 1881 respectively, Oris and Mantis Van Sweringen (often referred to as “the Vans”) started out as assistants at a fertilizer shop in Cleveland, Ohio. By 1900, they had begun a plan to develop the Cleveland community Shaker Heights into a top of the line suburb. Needing to develop high speed transport to bring in residents and allow them expedient routes to and from work, the Van Sweringens stumbled into railroad investing. By 1930, they would transform Cleveland forever and own the largest railroad empire in the world, stretching roughly 30,000 miles across the nation. Fortunately for the nation, since many rail lines and other aspects of infrastructure had fallen into disrepair in the wake of an 1893 economic depression, the brothers oversaw many renovations and standardizations as they became some of the nation’s first billionaires.

Yet they weren’t outgoing at all. In fact, the brothers made a point of not promoting themselves. They were lifelong bachelors who shared a bedroom in their Shaker Heights mansion. In the rare instances they made public appearances, they always did so together.

Unfortunately for them, the Van Sweringens had their investments in exactly the sorts of assets that were the most devalued during the 1929 stock market crash. Within six years, they would sell off their once $3 billion empire for fire sale prices in 1935. Within a couple years both brothers died, and without a fortune or progeny to carry the torch for them all the properties they’d once owned were renamed until their vast influence was mostly erased.

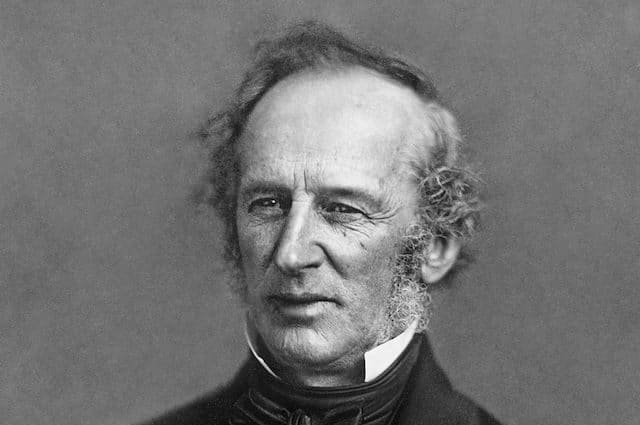

9. Cornelius Vanderbilt

This tycoon preceded the Vans by about a century and oversaw even more massive changes in America’s infrastructure. Born in 1794, he dropped out of school at age 11, bought a passenger boat in 1810, and then ran a government supply fleet for the War of 1812. From there he expanded his shipping so that in 1829 he had a shipping business that vied for control of Hudson Bay shipping, and was a millionaire by the 1840s. By the 1850s he expanded into rail projects which would leave him and his family so wealthy that they literally controlled 10% of all dollars in circulation.

Upon his death in 1877, a number of mad habits and plans he had came out since members of his family were claiming he was not of sound mind when he wrote his will. The most notable of these was his plan to convert all of Central Park in New York City into a statue of George Washington that would be the tallest man-made structure in the world, a project for which he went so far as to commission blueprints. For all the fuss over the will, almost the entire fortune was lost by the family within a generation, which is why you’ve heard much more about the Rockefellers or the Carnegies as shorthands for wealthy American dynasties.

8. Charles Lee

While the Revolutionary War general Harry “Lighthorse” Lee is relatively well-remembered, General Charles Lee dwells in obscurity. Born in 1731, he served in the French-Indian Wars and so he was redeployed to the American colonies in 1773. He switched allegiances to the Americans and resigned to join the Continental Army, which he quickly rose through the ranks. By the start or the Revolutionary War he was considered the most experienced general in the Continental Army, and basically saved it during the 1776 New York Campaign when he convinced Washington to retreat from a hopeless situation.

Even before the war Lee was getting a reputation for being erratic. John Adams called him an “odd creature.” It was an opinion Lee couldn’t help but support when he wrote Adams to bluntly admit that he found dogs preferable to people. In 1777, he was captured by the British while sneaking away from the Continental Army to hunt for a sex worker. He had to be released in a prisoner exchange.

Contrary to the aforementioned Vanderbilt, Lee was unusually open in his contempt for Washington’s abilities as a leader, and it was this more than anything that caused him to be relieved of command. He lost his faculties to an extent where he spent his last days living in squalor with his dogs and passed away in 1782, before the Revolutionary War officially ended and too early to valorize his name is posterity. However decades later it was revealed through private papers that Lee had been conspiring with British command to betray the Americans in a manner similar to Benedict Arnold, though he was court martialed before he could act on these plans. It’s understandable then that despite his vital service to his country he’s one of the Revolutionary generals that doesn’t get talked about.

7. Monk Eastman

Not every person who was influential in their time needed legal business or the military to confer legitimacy on them. Edward Eastman was born in Lower Manhattan in 1875 and by the 1890s he was working as a bouncer at New Irving Hall, an upscale dance hall where he earned a reputation for toughness among criminals and made connections with Tammany Hall politicians. His gang grew to a staggering 1,200 people, which was enough to intimidate voters and drive vote counts until Tammany Hall became overwhelmingly powerful. Eastman’s wars changed the face of gangs, including beginning the American tradition of drive-by shootings. Although the wars got out of hand to an extent where Eastman was sent to prison for five years in 1904, during WWI he was able to redeem himself on the battlefield until he became something of a national hero. Not bad for a guy who once considered his most redeeming feature the fact he took off his brass knuckles before hitting women.

Beyond Eastman’s penchant for violence, he was notorious for having an obsession for pigeons. Not only was the only legal job he ever held, he owned literally thousands of them. He would physically attack people for abusing animals of all kinds. That’s the sort of guy that could run a criminal organization which changed the shape of politics.

6. John Randolph of Roanoke

Returning to the world of politics, John Randolph was born in Roanoke, Virginia in 1773, and by the time of his death in 1833 he had been a member of the US House of Representatives, US Senate, and Ambassador to Russia. He was such a contentious figure that he clashed with every president, most notably Thomas Jefferson who he charged had abandoned small government principles. In 1806 he split from the then Democratic-Republican party and formed the “Old Republican” party, essentially shaping the political divide that we know and love today. His ability to do this was largely attributed to his great oratory skills, particularly impressive since a childhood ailment was believed to have disrupted his adolescence so that he never went through puberty and was left with a child’s voice, a compromised immune system, and lifelong impotence.

Randolph’s physical ailments were about on par with his eccentricities, which his colleagues in congress absolutely had to deal with as well. He openly drank in the chambers of commerce so that a brief speech took three hours. He brought his dogs into the House Chambers. At one point when a meeting was adjourned owing to Randolph’s bad health, his colleague Willis Alston said “the puppy still demands respect!” Randolph responded “Alston, if it were worth while, I would cane you. And I believe I will cane you.” Then, decades before the infamous Charles Sumner caning, Randolph beat up Alston. Considering his obvious love of dogs, you’d think he would have found such a label flattering.

5. Lucy Parsons

Born in a slave 1853 to what was known then as a mixed race family, Lucy Parsons seems to have been set on the path from rank and file labor activist to history-making firebrand leader by a miscarriage of justice. Her husband was hanged in 1886 for supposedly masterminding the Chicago Haymarket Riot, despite a lack of evidence in the trial so pronounced that several of the convicted were later pardoned. Such was her drive and influence that she would be labeled by the Chicago Police “more dangerous than a thousand rioters.”

Where Parsons parted from general progressive/labor rhetoric and from sanity was in the severity of her language. She literally said of the rich “Let us kill them without mercy, and let it be a war of extermination without pity.” When Franklin Roosevelt’s administration began the New Deal in 1933 which brought about many of the goals for which Parsons had advocated, she was furious because she felt it was a half measure and that only a full revolution would do.

So it was that, when she died in a fire in 1942 at the age of 89, many people believed it was a suicide.

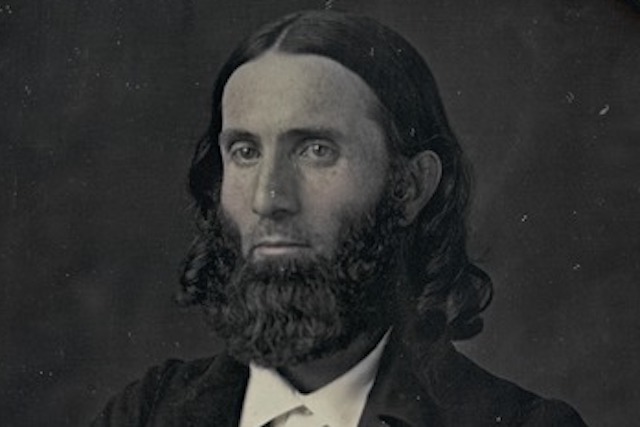

4. Charles Burleigh

Lately there’s been increased interest in more forceful advocates for the cause of abolition, such as John Brown and Nat Turner. Newspaper editors and columnists like Charles Burleigh didn’t live such dramatic lives and yet their contributions were also significant. In 1835 the 25-year-old Connecticut native abandoned a law career to become the public face of the Middlesex Anti-Slavery Society. He was so effective in advocating the cause and organizing abolitionist movements that when in 1836 a speech he was giving in Mansfield, Missouri was attacked by 20 pro-slavery toughs, the fallout still swelled abolitionist ranks by 200 people, which were significant in keeping Missouri from becoming a full slave state before and during the Civil War. He also arranged routes and Samaritans for the Underground Railroad.

All this despite an appearance that even his colleagues said worked against him. Early in his life he declared he would not cut his hair until slavery was abolished in the US, which not only meant he had some of the longest hair and the bushiest beard in the US but he put his hair in ringlets, which were wildly unfashionable at the time in general, let alone for a public speaker. Since he lived until 1878, he at least could have cut his hair into something relatively normal. If there’s one thing this look into American history is showing us, it’s that in the 19th Century a person could be a high profile success while flying their freak flag astonishingly freely.

3. Gouverneur Morris

In many ways, Gouverneur Morris was effectively the anti-John Randolph. He was a tall, strapping fellow notorious for his romances, and an early advocate for a strong federal government to an extent that he both wrote the preamble of the US constitution and oversaw the phrasing for the rest of the document. He also notably wanted to abandon the constitution he did so much to write by 1812, believing that his home state of New York should secede. The closest he came to a similarity with his conservative junior Randolph was that he lost his leg and at one point practically skinned his arm with scalding water.

Now when I say he was notorious for his romances, that includes such acts as a liaison with novelist Adelaide de Flahaut in her governess’s convent and the Louvre. He also had a very curious habit of climbing church steeples. You’d think such a powerful and accomplished man wouldn’t feel a need to so strongly overcompensate.

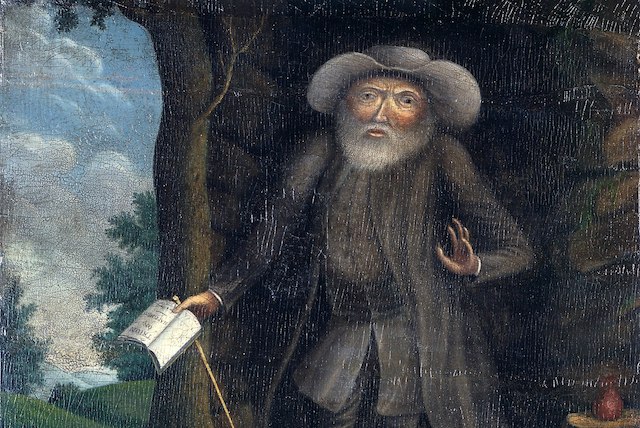

2. Benjamin Lay

While Charles Burleigh lived to see American slavery ended (to a point) Benjamin Lay was so far ahead of his time he had no such satisfaction. Born in Essex in 1681, he initially worked as a glove maker then became a farmer, then a sailor 1701. By 1717 he had sailed to America and joined the New England Quaker community and then quickly began antagonizing it through interrupting services, advocating vegetarianism, never wearing footwear, and refusing to drink tea. In 1731 he became even more vociferous though also immeasurably more righteous when he took a trip to Barbados, was appalled by the treatment of slaves, and returned to Quaker communities denouncing the Peculiar Institution. His most significant writing, All Slave-Keepers That Keep the Innocent in Bondage, Apostates, became a foundational document for the Atlantic abolitionist movement after a mass printing in 1738 by no less a historical figure than Benjamin Franklin himself.

He was also utterly uninhibited when it came to more physical denouncements of slavery. At one point he went to a service in a cloak, then tore the cloak off to reveal he was wearing a military uniform and holding a hollowed bible. The bible was hollow because while vocalizing the evils of slavery, he stabbed the bible, which had a bladder full of red liquid in it which he then splattered on slave owners that were present, one of the few religious lectures with a splash zone. This and such acts led to him being banished from the Quaker community, though by the time of his death in 1759, he had lived to see the Quaker community begin adopting his stance en mass and was buried in a Quaker cemetery.

1. James Otis Jr.

Speaking of fiery Colonial orators, we’ll be closing out on a Harvard lawyer born in 1725 in West Barnsdale, Massachusetts. In 1761, he resigned his commission as Massachusetts’s advocate general to protest Writs of Assistance, laws which allowed agents of the crown to search anywhere in the colonies for evidence of smuggling. On February 24, 1761, he gave an impassioned five hour speech denouncing the laws and the monarchy itself, which won many Bostonians over to the cause of independence. Audience member and second president John Adams wrote that the revolution was “then and there born.” He continued to give similar speeches against other arbitrary abuses of royal power throughout the 1760s and even collaborated with Samuel Adams in writing letters of protest which infuriated King George III himself.

Otis was noted for having wild mood swings between rage and despair. Unfortunately for his place in history, he was in a sense beaten into submission in 1769 when he confronted a royal commissioner at the British Coffee House near the Boston Wharf and was severely wounded by loyalists. The mugging left him too traumatized for further advocacy or other political work, and thus he had to sit out the revolution in the 1770s during the most momentous years. The most notable aspect of his final years was that he spent them vocalizing a wish that he be killed by lightning, which he was. As satisfying as that might have been, he deserved better.

Dustin Koski would like to thank David Anthony and Gareth Reynolds of The Dollop Podcast for inspiring this list.