Today, most people know that radium is a radioactive substance which should be handled with extreme care. However, things were different during World War I, when people handled it with few precautions like there was no tomorrow … which meant that to some of them, there wasn’t. The most tragic tale of this carefree early approach to radium is the story of the Radium Girls — a group of unsuspecting factory workers who found out about the dangers of the element they were handling the hard way. This is their terrifying story.

Radium the material

Chemistry and physics legends Marie and Pierre Curie discovered radium in 1898. At first, the highly radioactive material was very difficult to extract and there were only minuscule amounts available, and the Curies became extremely wary about the stuff after suffering multiple radiation burns from handling it. In fact, the Curies’ apprentice Sabin von Sochocky once heard Pierre say that he “would not care to trust himself in a room with a kilo of pure radium, as it would burn all the skin off his body, destroy his eyesight and probably kill him.”

In 1913, von Sochocky and another physician called George Willis experimented with radium and created a luminous, radium-based “paint” that made things glow in the dark. This paint would go on to destroy hundreds, possibly even thousands of lives.

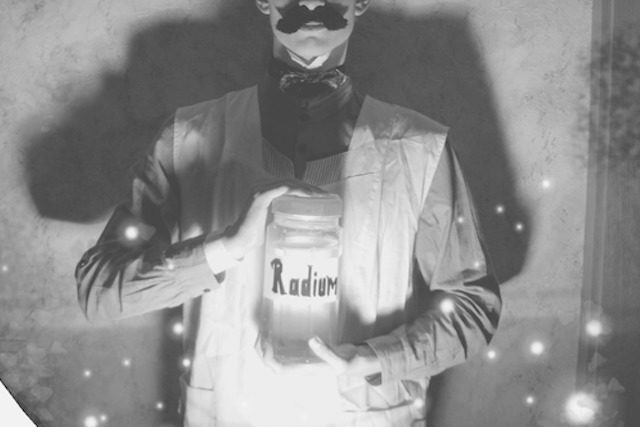

Radium as a beauty and health product

Von Sochocky and Willis were extremely familiar with radium’s dangers — in fact, von Sochocky once hacked off one of his fingers when it had become tainted with the radioactive element. Unfortunately for the radium girls, the information about the material’s dangers was largely unavailable to anyone outside the scientific community. Because it had been successfully used to treat cancer in the early days, people had started to think of it as an all-healing superdrug.

The media praised radium as a miracle substance with no negative side effects, and people were ingesting elixirs containing trace amounts of it daily, much like you’d take vitamin pills. Radium was viewed as a cure for arthritis and other ailments, and it featured in all sorts of products from cosmetics and toothpaste to jockstraps and lingerie, and even food and drink. In hindsight, this was particularly dangerous because ingested radium behaves much like calcium and goes right in your bones. Remember this nasty factoid, it will be important in a minute.

The radium girls emerge

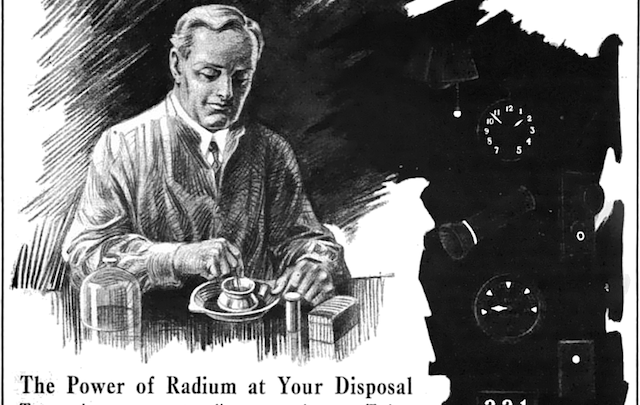

A paint that glows in the dark proved to be excellent for manufacturing things like glow-in-the-dark watches for military use, and military need was urgent because the WWI was raging. To capitalize on this demand, von Sochocky and Willis founded the U.S. Radium Corporation in 1917, to join other similar companies that had been operating since 1916. The 100+ workers of the company’s plant extracted and purified radium from carnonite ore, mixed the special radium paint the company called Undark, and hand-painted the watches.

The Radium Corporation was an excellent workplace for a lady, or so it seemed: The job paid well and was comparatively easy, and the company liked to employ young women because their delicate, dextrous hands made the work easier. That they got to work with a famously amazing health substance and aided with the war effort didn’t hurt, either. As a result, the company was a very desirable employer … for a while.

Poor precautions and planning

While the company’s founders certainly knew their way around radium and it was generally known that the element could potentially be hazardous in large amounts, no one bothered to inform the radium girls about the risks. The workers were assured that the glowing liquid they were working with was extremely safe, despite the fact that the managers of radium product corporations habitually wore protective clothing — the ones in the Radium Corporation had heavy lead aprons and only handled the radium with long ivory tongs.

Meanwhile, the women worked with zero protection, painting the clocks and mixing the paint from radium dust, adhesive and water. The plant that was so full of radium dust that it landed everywhere and made everything — and everyone — shine with an otherworldly light. To make things worse, the company taught the workers to paint watch dials with a special “lip, dip, paint routine.” The painters used a “lip-pointing” technique where they sharpened their brush to a sharp point with their mouth in order to conserve paint. Remember what we said about eating radium being incredibly dangerous? These women did it on a daily basis for years, just so the company could cut costs.

The glowing goddesses

The radium girls never really worried about putting radium-tainted brushes in their mouths. After all, all the magazines and newspapers told them radium was healthy, and the supervisors assured the paint was perfectly safe. How could a little ingested radium be anything but beneficial?

However, the brushes weren’t the only thing that upped the workers’ radium content. The strange luminous effect from the supposedly safe substance stuck on the women even after their shifts, and they glowed so much that it was immediately obvious who worked in the plant and who didn’t. Many of the “shining girls” wore this glow as a welcome perk, and when the workweek was over, some of them went the extra mile. Before they hit the town, they used Undark to paint their nails, hair and even teeth to literally light up the room with their smile. They were the Glowing Goddesses: Well-paid, proud of their work and quite literally radiant. They were happy, and many invited their siblings and close ones to join them at the plant. They had no way of knowing anything was wrong. And then the troubles started.

The horror begins

The questionable honor of being the first of the radium girls to die went to Mollie Maggia. In early 1922, she visited the dentist over a sore tooth. Soon, it transpired that he had another one. And another one. When they were removed, ruthlessly painful, oozing ulcers broke through her gums. Soon, the pains and aches spread to her limbs, rendering her unable to walk.

The doctors initially dismissed the symptoms as rheumatism and sent the pained Maggia away with a bottle of aspirin. However, by May, the radium poisoning had plummeted her into a shambling, zombie-like half-death existence. Most of her teeth were gone, and her entire mouth, jaw and even the bones in her ears could only be described as “one large abscess.” Despite this, no one seemed to realize just how serious her condition was until she took what would be her last trip to the dentist. When the dentist touched her jawbone, it snapped off. In a further examination, the dentist ended up removing poor Maggia’s upper jaw completely — by simply reaching in and lifting it out. Soon, her entire lower jaw had to be removed as well. To their abject horror, other girls started experiencing tooth and limb pains, and we can only imagine how scary it must have been for them to realize what was happening, knowing about Maggia’s gruesome condition and realizing they might very well be next.

By the time autumn came, Maggia’s lethal infection was already in her throat. It cut into her jugular, and caused a lethal hemorrhage that killed her in horror movie fashion at the tender age of 24. Her death was written off as syphilis. However, she was far from the last to die, and before the end of 1924, dozens of other girls had suffered a similar fate.

The ghost girls

The worst thing about radium is that it takes its time. Many of the women had swallowed trace amounts of the stuff over many years, and the element was slowly taking its toll. It stalked their bones and haunted their limbs, boring holes in their bodies and sabotaging their health in a number of terrifying ways. One woman was forced to wear a steel brace because the radium inside her was crushing her spine. Others suffered such deep fractures in their leg bones that their legs got shorter. There were cases of jaws disintegrating into gruesome stumps. And then there was, of course, cancer. Lots and lots of cancer.

What made it all even worse is the fact that the radium inside their bones and bodies never stopped glowing, and emitted a bright, deadly light from under their skin. The former glowing goddesses had become ghost girls — scores of radioactive walking dead, full of radiant death that couldn’t be removed from their bodies.

Deaths and ensuing investigation

Radium girls kept getting fired from their work for poor health and ultimately dying, but they found it difficult to attract attention to their struggle. However, fate eventually intervened when a wealthy, well-known man called Eben Byers also died from radium poisoning. It was his death that caused the officials to spring into action, and start reforming the industry in a way that was less dangerous for, well, pretty much everyone involved. Unfortunately, these improvements were mostly to protect consumers, and did very little to the women still actively working with radium.

In 1924, the U.S. Radium Corporation finally got around to commissioning a study of their own in an attempt to dismiss rumors about the supposed dangers of their trade. This didn’t go quite as expected: Industrial hygiene experts Katherine and Cecil Drinker, who were hired to conduct the investigation, found that not only was radium dangerous, but it was everywhere in the girls’ workplace, and when they changed clothes it got to their entire body. The Drinkers concluded without doubt that radium was the cause of all the health troubles, and although the U.S. Radium Corporation did its level best to present the findings in a light that was more favorable to them, the pressure was mounting.

Taking down Big Business

Some of the radium girls sued the company, which adamantly denied any and all connections between the mounting deaths and their product. When studies linking the two started to pop up, the U.S. Radium Company even bribed scientists to create other studies that showed radium was safe for the workers. Still, while von Sochocky and Willis had decided that their workers were running some sort of con against their company to finance their medical bills, the radium girls pushed on, armed with nothing but the knowledge that they were in the right. Eventually, they started gaining valuable allies. Famed pathologist Harrison Martland started looking into the case in 1925, and after examining the remains of poor Molly Maggia and other dead radium girls, she discovered they showed no symptoms of syphilis (their most common “official” cause of death).

Even Martland’s new-found evidence didn’t seem like it was enough to take the radium industry down. The case was so complicated and the radium industry was so powerful that almost every attorney turned the case down, thinking it was a no-win situation. In 1927, a lawyer called Raymond Berry finally agreed to represent the radium girls, but at that point, most of the women involved with the suit had mere months to live and the U.S. Radium Company made it clear it would drag its feet as much as possible. Small victories led to appeals, settlements were made, and even the victories came so late that many of the radium girls only got to use the money to finance their own funerals.

Still, the proceedings were heavily publicized and the radium girls were happy to give interviews and arrange fundraisers, which meant the cat was now out of the bag. The government had no choice but to act, and in 1928, the lip-pointing technique was forbidden and protective clothing was issued to every worker who was in contact with radium. Ten years later, the radium paint went the way of the dodo and the FDA banned “the packaging of products containing radium.” By 1939, the radium industry lost their final appeal at the Supreme Court, which officially verified the existence of radium poisoning as a cause of death. As an added bonus, the whole case was directly responsible for the creation of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Yes, you have the radium girls to thank for the existence of OSHA.

The legacy of the radium girls

The tragic tale of the radium girls reads like a horror story, and its casualties were horrific. More than 50 of the girls died from radium poisoning by 1927, and many of the hundreds that did survive faced serious health issues. It is estimated that the radium industry as a whole has caused thousands of women at least some health troubles. Bone cancer, anemia and leukemia were commonplace among the survivors, as were amputations, bone changes and collapsed vertebrae. Some suffered a version of poor Mollie Maggia’s half-life for several decades, and one unfortunate woman couldn’t leave her bed for a whopping 50 years.

However, despite their unfortunate fate, almost all of the radium girls worked to ensure that no one would have to suffer like they have ever again. They agreed to be measured and studied by scientists, which led to the kind of profound understanding of the effects of radiation on living human beings that would otherwise have been impossible to acquire. In fact, we owe almost everything we know about radiation’s long term effects inside the human body to the radium girls. Without them, the Manhattan Project could have argued against the rigorous safety measures imposed on them, in which case thousands of people who worked with actual nuclear weapons might have done so with precautions that amounted to little more than the radium girls’ “lip, dip, paint.” Without the research on them, it’s possible that President John F. Kennedy would not have signed the 1963 International Limited Test Ban Treaty, which prohibited atomic tests. In fact, the tragedy of the radium girls is directly responsible for the strict regulation of all forms of industries involving radioactivity.

The radium industry, however, took a little more time to go down. While the radium companies did take massive hits from them, radium paint was banned in 1938, and the world started moving away from the delights of radium by the time World War II was over, the last of the luminous processing plants wasn’t closed until 1978. Its radiation levels were 1,666 times higher than allowed.