The second half of the 19th century was a prosperous period for American paleontology. States like Wyoming and Colorado turned out to be full of rich bone beds containing never-before-seen fossils. Those who would find them assured their places in the annals of history.

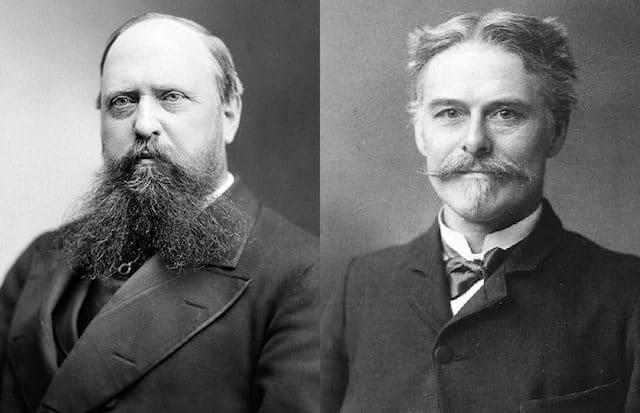

With such high stakes, it is understandable that there would be a sense of competition between scientists, but the feud between Othniel Charles Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope went far beyond your typical professional rivalry. These two men ended up hating each other and would go on to sacrifice career, money, and legacy just to see the other one destroyed in a bizarre conflict known as the Bone Wars.

10. The Boneheaded Mistake

It is difficult to say exactly when Marsh and Cope decided they hated each other. When they first started meeting professionally, the two appeared to have an amiable relationship, but perhaps behind closed doors, they found each other grating.

An unofficial start to the rivalry happened in 1869 when Cope presented his latest discovery, the Elasmosaurus. This was meant to be a moment of triumph for the young paleontologist, but he made a half-witted blunder that turned it into a grand humiliation.

Nowadays, we know that Elasmosaurus, and most other plesiosaurs, for that matter, have really long necks. Cope thought that the neck was a tail so he stuck the head at the short end which, in reality, was the actual tail.

Marsh pointed out that the vertebrae were positioned incorrectly which led to an argument. The two decided to defer to esteemed naturalist Joseph Leidy. According to the story, Leidy inspected the exhibit, removed the head and placed it at the other end. Later, he also published an official correction to Cope’s paper.

It is a little curious that only Marsh earned Cope’s wrath with this episode. Someone else would have surely spotted the error eventually. Maybe it’s because the two already disliked each other, by this point, and this was just more fuel for the fire. Or maybe it wasn’t as much what Marsh said, but how he said it, and how he kept flaunting Cope’s mistake in public afterwards.

9. A Clash of Cultures

Besides the fact that both Cope and Marsh were paleontologists, they appeared to be polar opposites which, assuredly, could have caused friction between the two.

Cope was born into a wealthy Quaker family and considered himself a gentleman. Marsh was a bit rougher around the edges, having grown up poor. Fortunately for him, his uncle was George Peabody, one of the richest and most generous philanthropists of his time, who paid for Marsh’s education.

The two also had different ideas on how to go about being a paleontologist. Cope was a man in the field. He wasn’t afraid to get a little dirty and traveled frequently to dig sites or as part of the United States Geological Survey (USGS).

Marsh, on the other hand, preferred to do his work from the comfort of his office, studying fossils that his agents brought to him. He persuaded his uncle to fund the Peabody Museum of Natural History at Yale which, of course, was rewarded with a position as Professor of Paleontology at the school for Marsh. This was more of a symbolic gesture as Marsh’s own inheritance meant that he didn’t have to teach to make money. In fact, during his career, he only led four fossil-hunting expeditions with students between 1870 and 1873.

As prominent naturalists, Cope and Marsh had strong, but different opinions on a major topic of their day – evolution. Marsh was a staunch supporter of Darwinian natural selection, but Cope was one of the founders of Neo-Lamarckism, a school of thought that asserted that adaptive traits acquired during an organism’s lifetime could be inherited directly by offspring.

8. Early Expeditions

Cope and Marsh had the luxury of starting their paleontological careers at a time when the American West had just recently shown to be a treasure trove of fossils. Their earliest expeditions were marked more by a constant game of one-upmanship than the two actively trying to sabotage each other.

In 1872, Cope joined a USGS survey led by Ferdinand Hayden. The position wasn’t paid and Cope even had to cover some of his own expenses, but it provided him with great opportunities and resources to collect fossils.

The journey was incredibly fruitful and Cope discovered dozens of new animal species, but the extent of support afford to him had a limit. At one point, the paleontologist traveled to a new site and expected to find men, horses, and equipment waiting for him, but he was alone. He paid for a crew out of his own pocket and ended up unwittingly hiring a couple of men who also worked for Marsh, which angered the latter.

For his expeditions, Marsh traveled into the Dakota Territory and struck a deal with Chief Red Cloud of the Sioux. In order to gain his help, the paleontologist would pay for fossils and lobby on behalf of the Sioux in Washington, D.C., raising concerns about governmental corruption and fraud. For his part, Marsh actually kept up his end of the bargain, prompting Chief Red Cloud to call him “the best white man [I] ever saw.”

These first expeditions marked the beginning of an unfortunate trend for the two scientists, one that would end up tainting their credibility. They both got in the habit of making rushed telegrams describing all of their new discoveries, leaving the full accounts until they returned home. They didn’t care about being accurate, as long as they were first.

7. A Deal with Lakes

By its nature, paleontology is not a solitary profession. Although most of the lab work can be done alone, actually securing fossils requires interaction with agents, geologists, and other paleontologists. Therefore, many other people like Joseph Leidy or Ferdinand Hayden found themselves unwittingly part of the Bone Wars, forced to take a side.

Another one of these men was Arthur Lakes, now considered one of the founding fathers of American geology. He inadvertently strained the fraught relationship between Cope and Marsh even further when he wrote to both of them to inform them of new fossil discoveries he made in Colorado.

At first, he only wrote to Marsh. He was slow to answer back so Lakes also inquired with Cope. Eventually, Marsh responded, clearly interested in Lakes’ findings. When he heard that Cope also knew about them, he sent an agent to meet with the geologist and strike a deal. Understandably, Cope was furious when he learned that Lakes rescinded his offer and started working with his nemesis.

The arrangement turned out very well for Marsh. Among other things, Lakes collected for him a mysterious giant serrated tooth which was later proclaimed to be the first T. rex tooth ever recovered.

6. War at Como Bluff

Wyoming was the true battlefield where the Bone Wars were “fought” and Como Bluff was its epicenter. During the late 19th century, the area was revealed to be one of the richest deposits of fossils in the country.

In the late 1870s, the Union Pacific was building the First Transcontinental Railroad through the region. Two workers, William Reed and William Carlin, sent word to Marsh that they found a lot of bones. The scientist sent an agent to investigate their claim. Upon hearing that other parties were also interested in the area, Marsh quickly drew up a contract to secure the duo’s services. According to the agreement, Reed and Carlin would do their best to keep Cope out of the area.

They actually did the opposite. By 1878, rumors of the major finds were being leaked. The Laramie Daily Sentinel published stories on the matter, including the “exorbitant” prices that Marsh was, apparently, paying for the fossils. That last part was exaggerated by the two railroad workers, ostensibly to gain leverage for a better deal from other parties. Indeed, by the end of 1878, Carlin had switched to working for Cope.

5. The Gloves Are Off

The excavations at Como Bluff lasted for 15 years as both Marsh and Cope opened as many quarries as possible. Their men routinely engaged in espionage, bribery, and even outright theft. On one occasion, the rival crews even started an all-out fight by throwing rocks at each other. Perhaps the most heinous action from two supposed men of science was that they sometimes had fossils purposely destroyed or entire excavations filled in to prevent them from falling into enemy hands.

For the workers, the years spent at the dig sites were not happy ones. As neither Cope nor Marsh were typically present at the quarries, they left other men in charge such as Reed, Lakes, Carlin, or Frank Williston, one of Marsh’s agents. Tensions often rose and boiled over between them and, sooner or later, all of them quit. Carlin and Williston even went independent, selling their finds to the highest bidder.

4. Front-Page News

For most of its duration, the rivalry between Cope and Marsh was contained within the scientific community. As you might imagine, the average person had little knowledge of the goings-on within the paleontological world, let alone the petty bickering, sabotage, and stealing that went on between two bitter scientists. That changed in the mid 1880s when Cope saw his opportunity to ruin Marsh professionally.

As mentioned previously, Cope, at one point, worked for the USGS under Ferdinand Hayden. This was a pretty sweet gig for a paleontologist so, naturally, Marsh wanted it for himself. He got his wish when one of his friends named John Wesley Powell became the new director of the scientific agency in 1881. However, a few years later, Congress wanted to investigate the administration for wasteful spending of government funds.

Cope relished the idea that Marsh might be in serious legal trouble but, unfortunately for him, both Marsh and Powell got off scot-free. Not one to easily concede defeat, Cope reached out to a journalist for the New York Herald and offered to reveal to the world the real Othniel Charles Marsh.

The writer saw past Cope’s obvious hatred of the other paleontologist and sniffed out the real story. The newspaper ran the story with the headline Scientists Wage Bitter Warfare. The Bone Wars were now front-page news.

3. Mutual Assured Destruction

When he went to the media, Cope spoke of all the times that Marsh had bribed people or spied on his rivals, conveniently leaving out the parts where he did the same. Moreover, Cope had kept a journal for almost two decades. In it was every scientific error and every wrongdoing that Marsh had been guilty of in his career.

Unsurprisingly, Marsh retaliated in the same way. He brought up all of Cope’s mistakes and foibles, going all the way back to his “butthead” elasmosaurus. For a while, it seemed like every newspaper edition contained either a rebuttal or a new accusation from the two.

In the end, neither side benefitted from this public airing of dirty laundry. Marsh lost his position with the USGS while Cope also lost his job as head of the National Association for the Advancement of Science (now AAAS).

Their reputations were in tatters, but the Bone Wars also left both paleontologists financially ruined. Cope had to sell off large chunks of his beloved fossil collection to make ends meet while Marsh mortgaged his house and had to rely on a salary from Yale.

2. One Last Challenge

The rivalry ended in 1897 when Cope passed away, but he launched one final challenge in death – he wanted to have his brain measured and compared against that of Marsh.

Back then, there was a scientific belief that brain size was in direct correlation with intelligence. Men who held racist views, like Cope did, relied on this argument often to show that the white race was superior. In this case, Cope wanted to show conclusively that his brain was bigger and, therefore, he was smarter than his archrival.

Cope donated his body to science. Unfortunately, Marsh never accepted the challenge so, although he died two years later, his brain was never measured.

Every time a new species is described, it is standard practice for one individual to be declared the type specimen. However, when Carl Linnaeus outlined the modern taxonomical system in the early 18th century, he left out that part for Homo sapiens, famously writing instead “Nosce te ipsum” – Know thyself.

There was a legend that part of the reason why Cope donated his body was because he wanted to be made type specimen for humans. Scholars have dismissed this idea. Towards the end of his life, Cope was missing most of his teeth. Sordid rumors said that he had syphilis. Either way, he would have known that he would be ineligible.

1. One Step Forward, Two Steps Back

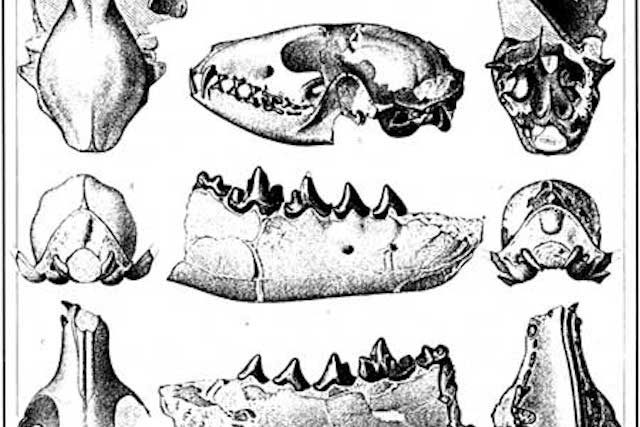

One positive thing about the Bone Wars that gets mentioned often is that, at least, it led to a boom in paleontology. Cope and Marsh discovered and described almost 140 new dinosaur species combined, not to mention over a thousand other kinds of animals.

However, their work has been criticized for being incredibly slapdash in an effort to make more discoveries. As the two were concerned with having a “higher score” than the other, they often made mistakes, misidentifications, or simply proclaimed new species based on insufficient evidence. Efforts to accurately reclassify all of their findings are still going on today.

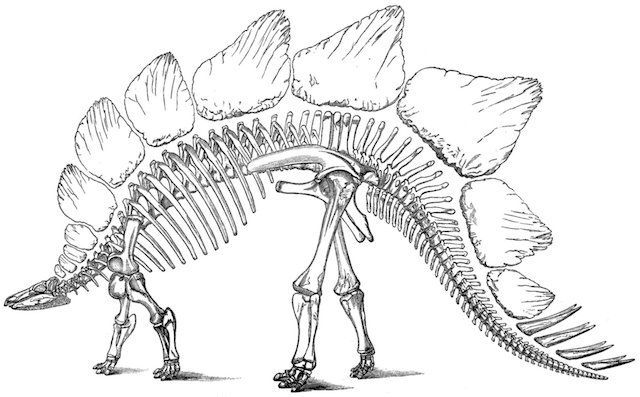

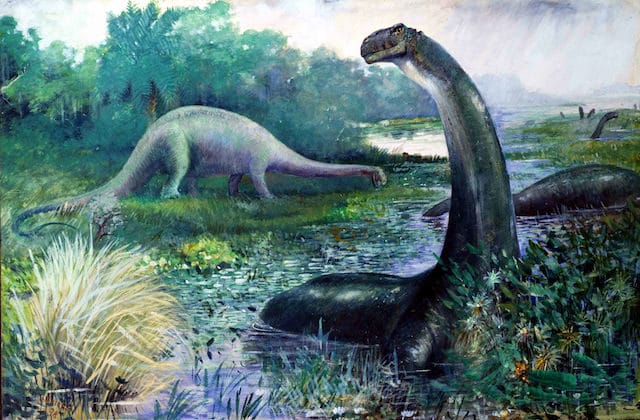

The most famous example of this issue is the Brontosaurus. Discovered and named by Marsh, it was always said to resemble another one of his findings, the Apatosaurus. Just a few years after his death, other paleontologists were already arguing that they were not distinct enough to be placed in different genera. Eventually, they were reclassified as one.

During the 1990s, Robert Bakker suggested that the two dinosaurs might, in fact, be different after all. In 2015, a new study concluded that Brontosaurus and Apatosaurus belong in separate genera. That is the current thinking, but not all paleontologists have come around to it.