Most history classes on America cover the discovery of the continent, the founding of early colonies likes like Jamestown and Plymouth Rock, then seem to skip to immediate lead-up to the American Revolution. That’s a pity, because the colonial centuries were some of the most fascinating in the history of the United States of America. As is the case so often in history, “fascinating” actually means “hellish.”

Even beyond the unrefined technology and the roughness of the untamed country, there were many challenges to life across the pond, some unique to the place and time. Perhaps this list will make some people slightly happier to be an American. More likely it will make them happier to not be an American back then.

10. Captive Market

While it’s common to look at Colonial Americans as a self-sufficient bunch, a collection of surviving documents from George Washington himself paints a very different picture. In 1757 he was writing letters requesting everything from raisins to furniture to sponge toothbrushes. The fact was that American industry was woefully unable to process or manufacture a huge array of basic commodities, and were required to purchase all such goods from Great Britain.

Many British manufacturers were well aware of the fact their clients were effectively at their mercy, so many shipments either lacked some of the products that had been ordered or contained spoiled or broken wares. Not to mention all the goods that were dumped on the colonists because they were unfashionable to the point of unsaleable in Britain. “It’s good enough for America” became a popular saying on the island for shoddy products. For all the talk of taxation and representation, this was likely a powerful motivating factor for the revolution.

9. Numerous Surprising and Frustrating Currencies

The most obvious choice for 13 colonies under the control of a single empire would be to simply use the mother country’s currency, yet little British currency was available in the colonies before the Revolution due to a massive trade deficit, which is hardly surprising for colonies that are effectively a captive market. So for internal transactions, alternatives were vital, and further complicated by just how united the colonies really weren’t much of the time.

Throughout the colonies, the golden Spanish coin known as the “piece of eight” was the most popular, since Spanish colonies in the West Indies, Mexico, and Florida meant a much steadier cash flow. On the basis of specific colonies, Virginia and North Carolina used tobacco leaves for currency. Since those were hardly convenient or durable, receipts for tobacco transactions began being used like checks. Massachusetts used wampum, which were basically beads made out of shells. While on paper the official currencies were supposed to be counted out in pounds, the amount of uncertainty over exchange rates must have meant it was likely essentially haggling.

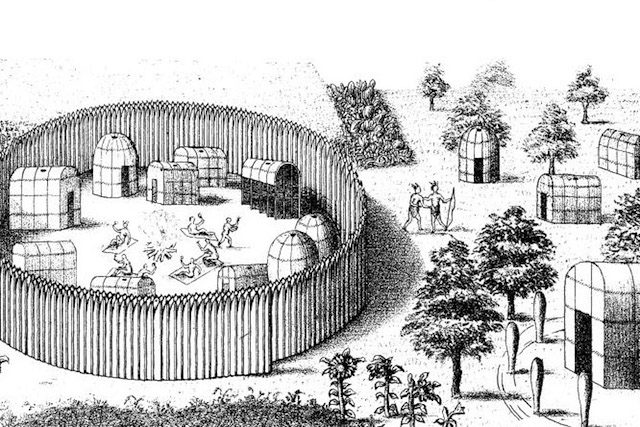

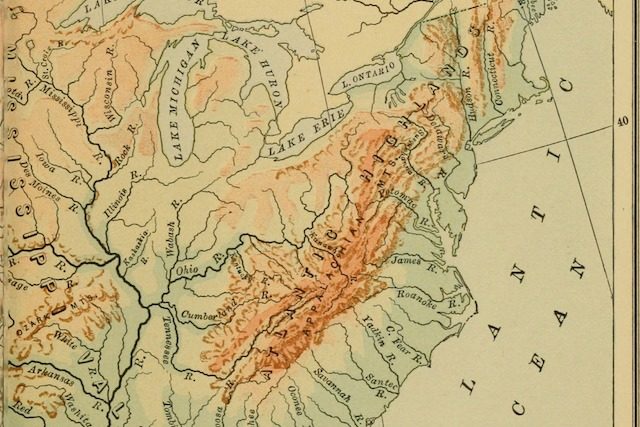

8. Many, Many Wars with Natives

Although many popular portrayals of the early interactions with Native tribes try to emphasize uplifting aspects of interactions with individuals like Squanto or Pocahontas, from practically the beginning the colonists faced enemies that were willing to drive them back to the sea. Each conflict seemed to be labelled a different war despite their widely varying degrees of scale. For example, in 1715 the Yamasee War began with an alliance of native tribes attacking colonists that were encroaching on their land in South Carolina, dispatching 90 of them at the outset. It took two years of raids before the colonists were able to reinforce themselves sufficiently to break up the alliance. The largest conflict was known as King Philip’s War in New England from 1675 to 1676, which cost 600 colonists and 3,000 Native Americans. Neither side spared their enemy’s civilians or children

Enthusiasm for war among some of the colonials that it could prove disastrous for their own leaders. For example, in 1676, Nathaniel Bacon in Virginia was so determined to attack local tribes that when Governor William Berkeley forbade it, Bacon’s rebellion would result in him sacking and burning down Jamestown. Berkeley ultimately won the conflict and had all leaders in Bacon’s Rebellion hanged, but the damage had already been done, including relations to previously friendly tribes.

7. The Prolonged Witch Hunts

The 1692 Salem Witch Trials dominate historical memory of witch hunts in America, but they were by no means the beginning or the end. The first colonial witchcraft trial began in 1647 in Hartford, Connecticut and resulted in Alice Young being sent to the gallows. In 1662 Hartford would have a real wave of witch trials which saw seven people tried and four people hanged. Coincidentally, Hartford had a witch hunt wave of its own the same time Salem did, though without such a large body count. It was hardly a daily occurence or equally likely in all colonies. North Carolina, for example, only had one witch trial. Considering the flimsy pretexts that could be used for accusations, it was a risk that hung over every personal grudge, since that seemed to be the primary motivation for accusing someone of witchcraft.

As it happened, Salem’s Witch Trials seemed to inoculate much of the rest of the country to the practice, as the massive loss of life left other communities wary of the potential consequences and increased the standards of evidence. The aforementioned trial in North Carolina took place in 1703 and was thrown out of court for being baseless. The last colonial witch trial occurred in Virginia in 1730, the same year that Benjamin Franklin himself wrote an essay mocking the whole notion. By 1735, Parliament wrote a new Witchcraft Act which decriminalized being a witch.

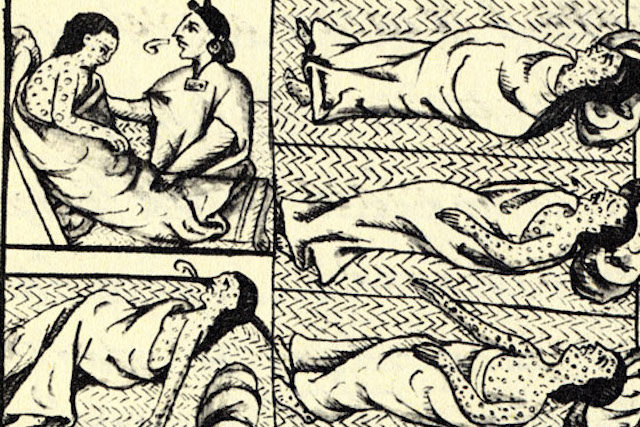

6. Poorly Fought Epidemics

It’s no secret that the Native Americans fell victim to the diseases brought by Europeans by the millions, and there’s some debate if the one deliberate attempt at this in 1763 at Fort Pitt worked. Given how well attempts to combat epidemics afflicting colonists tended to go, it’s possible that a sincere, concerted effort by the colonial powers to save natives could have made the situation even worse.

When one of the dozens of major epidemics that struck the colonial cities over the centuries occurred, the relatively isolated communities that were scattered throughout the colonies were often safe. Unfortunately for them, it was quite common for city folk to flee cities when an epidemic struck, sending out many unwitting carriers. For example, in 1721, a Boston smallpox epidemic sent 900 out of a city of roughly 11,000 fleeing for the countryside. With that in mind, any village’s distrust of outsiders is much more understandable.

For the wealthy, there was a procedure that was dangerously ahead of its time called “variolation.” Variolation was a variation on vaccination where in the early stages of an epidemic a small amount of tissue (e.g. pus) from a confirmed patient would be introduced to the bloodstream of a healthy person so that they could build up an immunity. Because medical procedures and treatments were not as fully developed back then, the client would make the mistake of not socially isolating themselves after treatment, and so variolation would actually exacerbate the very epidemics they were supposed to fight against.

5. Egalitarian Bathing, Or Lack Thereof

Bathing as a habit seemed to go in and out of fashion, and for Colonial America it was in a fairly unfashionable position. It was believed that bathing excessively would remove the natural oil in a person’s skin, which would weaken the immune system. So the correct amount was believed to be once every few months, at least as far as full body bathing went. Surprisingly, this seemed to be the case for the wealthy and the poor alike. Also, many colonists didn’t bother with or have the materials for soap.

The preferred method of freshening up and becoming less pungent was to simply change washed clothes, a pretty difficult practice for those who were only wealthy enough for one set.

Flowers and herbs were about the best that could be done for deodorants. It’s hard to believe those would be up to the task of covers months worth of accumulated body odor.

4. Anti-Conservation Campaigns

For those who feel climate change is a new notion, it actually predates the independent United States by a few decades. The mindset about it was vastly different, however. It was thought that by clearing forests, the colonists were actually improving the environment. As John Adams wrote in 1756, “the whole Continent was one continued dismall Wilderness… Now, the Forests are removed.” Thomas Jefferson wrote in his 1782 work Notes on Virginia, “A change in our climate… is taking place very sensibly.” Ben Franklin also wrote about the issue in 1763, stating it was claimed that the snow melted faster on cleared land, although he felt that it hadn’t been proven conclusively.

It should be said that contrary to Adams’s claims, the Native Americans hadn’t exactly left the land untouched. For example, Mohicans had been using fire to clear the Hudson Valley in present day New York since at least 1000 AD. Though as far as we know, that was only to clear the land for farming, not to intentionally shift the climate.

3. Indentured Servitude: Promises Unfulfilled

Other TopTenz articles have described the fundamental differences between an indentured servant and a slave, but it’s not this site’s intention to downplay the hardships of an indentured servant. Although they were supposed to have complete freedom after five to seven year’s labor, a huge amount of them did not live to see the end of their terms. For example, among the indentured servants that arrived in Virginia from 1609 to 1616, three quarters of them were dead within a year of arriving.

As if that wasn’t bad enough, consider the companionship of those indentured servants. Between 1630 and 1680, there were 50,000 servants that arrived through Chesapeake Bay, 75% of the immigrants. Of those, somewhere between six in seven and four in five of all arrivals were men — meaning there were countless servants without spouses, children, or families during their final days.

That was likely a significant contributing factor to the next entry…

2. Lax Prostitution Laws

For millions of Americans Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter was required reading. Since the novel portrayed the crime of adultery worth having a shameful symbol on your clothing for life, it would be understandable for readers to assume punishments for arguably more debauched sexual sins of prostitution and pimping to be much worse. Legal records show that was not the case at all.

There are a relatively small number of cases of brothels (referred to as “disorderly houses”) being busted, but the worst the brothel owner faced was a small fine or being whipped a few times. In 1753, Bostonian Hannah Dilley was convicted of letting whores work in her home and the extent of her punishment was having to stand on a stool and hold a sign saying what she had done. Sometimes the police couldn’t even be compelled to properly raid a brothel, since they were easily bribed by food, money, and so on.

If anything, it was civilians that brothel owners had to worry about. While Minister Cotton Mather tried to launch a public campaign against them and found little support, working class people were more willing to go outside the law against brothels. There were a few incidents where mobs attacked and even burned down brothels. Even without the threat of arrest the prostitution is almost certain to be an arduous life.

1. Devastating Weather

The colonies were founded during the latter half of a time called the “Little Ice Age,” which is generally stated to have run from 1300 AD to 1750 AD. As such, the colonists were in for both frigid winters and summers which were unusually dry and hot at a time when they were particularly vulnerable. For example, in the winter of 1607 the famous and brand new colony Jamestown endured the James River, which was as large as the Thames, freezing solid, no doubt contributing to the aforementioned high mortality rate among indentured servants. There were numerous winters in the 1630s and 1640s that were just as severe, and even many of the milder winters were marked by immense snowfalls. Bear in mind that many travelers to the colonies at the time were sold on the idea that because the longitude of New England was roughly that of Spain and Southern France the climate would be very mild, so imagine how unprepared they were.

As if that wasn’t enough, Colonial New England and Virginia were unusually prone to hurricanes. In 1635, one left hundreds of homes were destroyed in and around poor Jamestown, Boston, and Plymouth, Massachusetts, leaving 46 dead in its wake. In 1667 Virginia was hit again by what became known as the Dreadful Hurricane. It destroyed roughly 10,000 homes, and ruined farms and fleets of ships. To exacerbate the situation for anyone trying to cope with the disaster, it was followed by 12 straight days of rain. Little surprise that the society which survived ordeals like that thought it could take on the Brtish Empire.

The realities of Dustin Koski’s life can be seen by following him on Twitter.