Although the word “Zulu” means “Heaven,” for generations Zulu warriors gave their enemies hell. From a small tribe as late as the 1816, they were organized and invigorated by the legendary Shaka Zulu to become the dominant kingdom in South Africa. Even when the British armies arrived with their advanced weapons, the Zulu soldiers were still able to give them a run for their money and sometimes defeat them in spectacular fashion.

What were the secrets of their military success? What did a Zulu warrior carry into battle? What was their training like? Let’s get to know these warriors from a bygone era better. You’ll likely find some surprises waiting for you below.

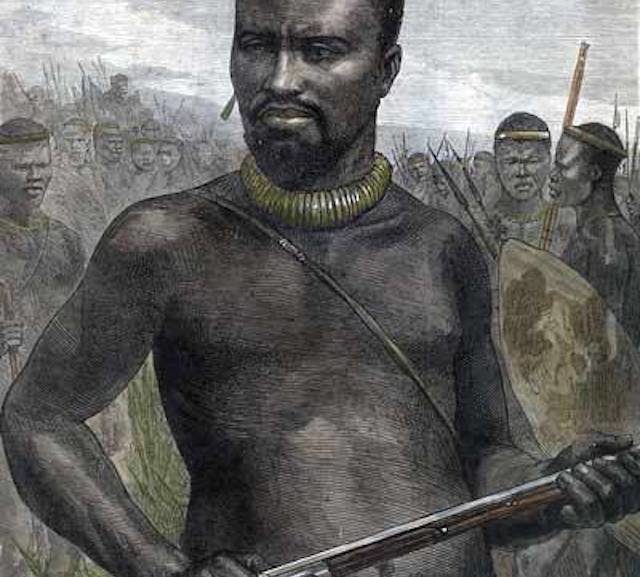

10. Shaka Zulu Redefined War

When Chief Senzangonka died in 1816, the Zulu were another unremarkable Nguni-Bantu tribe among hundreds and local wars tended to be relatively harmless affairs. The warriors of the Zulu tribes and their rivals would line up and be as likely to only throw insults at each other as spears. Considering that the tribe was estimated to have numbered only about 1,500 members, they could hardly be expected to field armies that could leave vast battlefields covered in the corpses of their enemies in their wake.

That changed when Senzangonka’s mantle was taken on by distinguished soldier Shaka Zulu. He began disciplining, organizing, and most importantly rearming his soldiers. Under Shaka, the Zulu began relying on shorter spears called assegai. Unfit for throwing, these spears required them to get up close with their enemies, and immediately the nature of combat became more personal and committed for the Zulu while becoming vastly more terrifying for their enemies. Within 12 years, the Zulu went from another modest tribe to a kingdom which fielded armies of more than 35,000. The Zulu Kingdom would only last a little over half a century before being destroyed by the British Empire, but its stamp on history would last.

9. The Great King Went Mad

While Shaka Zulu’s ambitions and statesmanship inarguably were momentous for the Zulu, they ended on a nearly tragic note. In 1827, Shaka’s mother died, and the grief of this drove the king insane. By the time of his assassination on September 22, 1828, he had banned the planting of new crops and the drinking of milk. Being pregnant was punishable by death, as was being the spouse of the offender with child.

There are historians that have cast doubt on the truth of these claims of Shaka Zulu’s homicidal despotism. Beyond European prejudices at the time, Shaka Zulu’s successor and half brother King Dingane had been one of the three people directly involved in assassinating the king and throwing his body in an empty grain pit. Dingane reigned for 12 years, and that was plenty of time to spread propaganda about the man he’d murdered to give his dominion the appearance of greater legitimacy as he spent much of his time killing Shaka’s loyalists. However justified Shaka Zulu’s murder was, he was still sufficiently loved by his people for a memorial to him to be constructed on what was believed to be the site of his death.

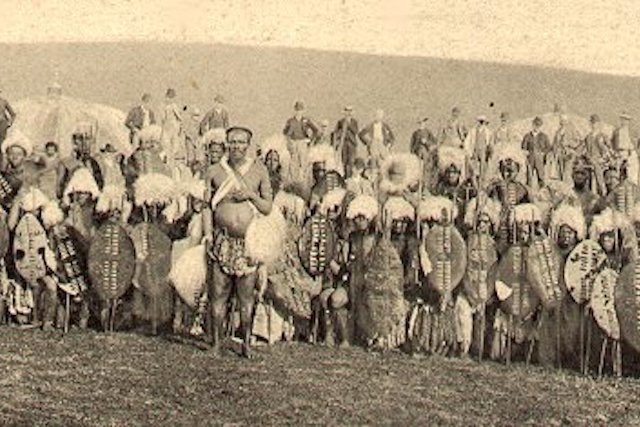

8. No Permanent Soldiers

The Zulu Kingdom did not have a specially designated, full-time warrior class. Every able-bodied man from age 18 to 40 was eligible to be called up to serve. They would be put into regiments called amabutho and given matching uniforms. The older soldiers were given seniority of rank. They fought the kingdom’s enemies, policed the communities, and at times were pressed into manual labor on domestic projects. While on duty they would be housed in barracks called the amakhanda.

Beyond the existence of the barracks, there was by no means enough of a supply reserve or infrastructure for the army to be assembled for prolonged periods of time. After whatever campaign they had been assembled for was judged to be complete, they were disbanded to return home to their farming, goat-herding, etc. This left the king with a timetable that was usually limited to only two to three weeks for full mobilization, one of the disadvantages which would spell the kingdom’s doom in the Anglo-Zulu War.

7. Horns of the Buffalo

The tactic Shaka Zulu’s troops became famous for as they conquered their neighbors was known as the “Horns of the Buffalo” or “Horns of the Beast.” In effect, the main body of troops would attack the enemy head-on while the fleet-footed soldiers would serve as the horns by running around both ends of the enemy line and attacking from the rear. It’s a strategy also known as a “double envelopment.” If pulled off properly, it could lead to the practical extermination of an enemy army.

The most famous example of the Zulu goring an enemy on the horns of the buffalo was the Battle of Isandlwana during the 1879 Anglo-Zulu War. Of 1,200 Colonial troops that were fully equipped with state of the art weapons, including artillery pieces and rockets, only about 60 survived the attack by King Cetshwayo’s army. It was a defeat that caught Europe completely by surprise, as up to then the Zulu armies were dismissed as only mobs of rabble that no modern army had to worry about.

6. Quick Gun Adopters

The initial mental picture most people will have of a Zulu soldier is someone equipped only with a spear, a club, and a leather shield. In the 1964 film classic Zulu, a few Zulu warriors shoot at the British soldiers for a short scene during the 1879 Battle of Rorke’s Drift. The character Commander Adendorff speculates that the Zulu had gathered them from fallen colonial troops at the Battle of Isandlwana, which had happened earlier that day. In fact the Zulus already had a stockpile of tens of thousands of guns from the Anglo-Zulu War’s outset that they’d been building up for years.

Zulu leaders realized shortly after the 1838 Battle of Blood River that they needed to get their hands on firearms. Ngidi ka Mcikaziswa, the Zulu commander for that battle, bitterly admitted that musket volleys were capable of making his warriors who’d always died facing the enemy turn tail. The Zulu Kingdom primarily turned to diamond mining and ivory harvesting to pay for all the imported guns, and unfortunately for them they tended to be stuck with outdated flintlock muskets, surplus from the Napoleonic Wars. They were only accurate at all for distances of about 50 yards, which was scarcely farther than a spear could be thrown. Ammunition was limited too, meaning that the Zulu weren’t able to train with the firearms very well. So guns were principally used to fire an initial volley before a charge, or to snipe their opponents with limited success.

5. Rorke’s Drift War Crime

During the aforementioned, highly-celebrated Battle of Rorke’s Drift, where roughly 140 British soldiers held down a mission converted into an improvised fort against as many as 4,000 Zulu soldiers, the fighting became so intense that the mission hospital was set on fire and some of the wounded were stabbed to death by the Zulu. This infuriated the Colonial troops. Although most depictions of the battle emphasize the gallantry of soldiers on both sides, what followed was one of the grislier episodes in the history of 19th Century warfare.

The 500 wounded Zulus were not merely put out of their misery through gunshots or bayonets. As the soldiers recorded in their own journals and memoirs, a wooden frame used to dry oxhides was turned into an improvised gallows. Many of the wounded Zulus suffered the particularly nightmarish fate of being buried alive. This was unambiguously a war crime, as Great Britain had been a signatory at the Geneva Convention 15 years earlier. Hard to feel very inspired about the battle after learning that.

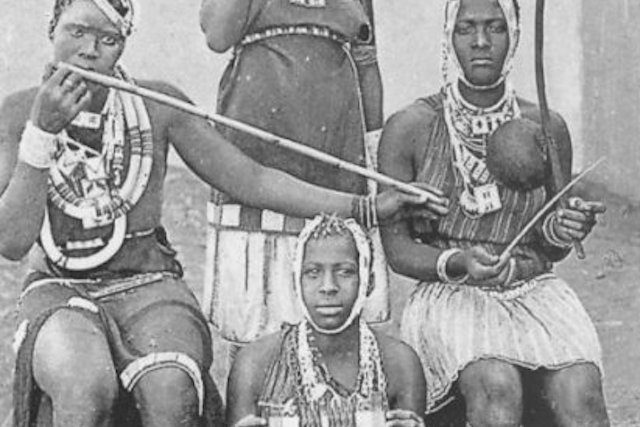

4. Civilian Shields

Although Zulu citizens were expected to spend the vast majority of their time living as civilians, they were still expected to have a leather shield made from the hides of their own cow or goat with them during much of their down time. There was a shield about nine inches in diameter called the umgabelomunye that was used for dancing, one called the iqgoka used as a status symbol for the youths, and one about two feet long used for hunting called the ihawu. High-ranking individuals would have an attendant hold a stick with a shield on it to provide a bit of shade. All the shields were expected to be decorated in a uniform manner with the rest of the tribe, usually by painting them black and white striped patterns.

War shields were a different matter. Those were the king’s property at all times, and kept stockpiled in his amakhanda between campaigns. This was done to prevent the soldiers from rising up and overthrowing the king. Considering the fate of Shaka Zulu, it was an understandable form of paranoia.

3. Battle Purification

Combat was truly a spiritual experience for Zulu army, and it came with a number of rituals. One of these was the drinking of a potions that cleansed the body in a very simple way: Inducing vomiting to get the evil spirits out. Even that was more palatable than dripping water on themselves which contained specks of human flesh, a practice which was supposed to protect their bodies to the point of invincibility.

Zulu warriors also had a very different perspective regarding scavenging from their fallen enemies. They felt they needed to take something from the enemy combatant that they’d just killed (usually a weapon, though a bit of blood also served) until they’d undergone a post-battle ritual cleansing. Further, soldiers who had just killed someone were to be treated with caution by their comrades. A soldier who just took a life would likely be so crazed with spirits of bloodlust that he wouldn’t be able to distinguish friend from foe.

2. The Rituals for a Fallen Enemy

Colonial soldiers didn’t just find the corpses of their comrades that fell into enemy hands with an extreme abundance of wounds. Sometimes the bodies were disemboweled after the soldier was already dead. A completely understandable initial impression would be that the mutilations were just Zulu soldiers showing their contempt for their fallen foes. The truth was that the post-mortem wounds were religious in nature, acts of solidarity and exorcism.

The stabbing ritual was called the ukuhlomula. Every member of a small unit of Zulu would stab the corpse of an enemy to demonstrate how they were unified in their purpose, similar to a team in a huddle all joining hands. It was originally a hunting ritual. Thus it was something of a sign of an enemy who had fought well, as if to say the soldier had been a particularly formidable prey or predator.

The disemboweling ritual was called qaqa. Corpses on a battlefield swelled up with necrotic gases, particularly those of well-fed people as British soldiers tended to be. The cuts thus prevented those gases from building up, since Zulu tradition interpreted those gases as being the dead person’s spirit attempting to escape into the afterlife. In short, both qaqa and ukuhlomula were usually acts of respect.

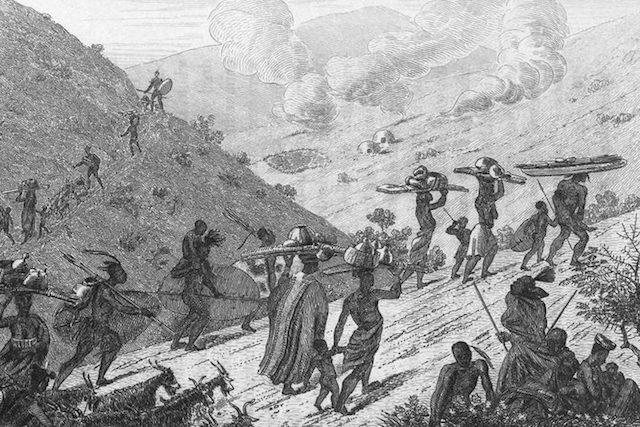

1. The Mfecane

While many students of history put Shaka Zulu on a pedestal for his innovations and his military successes, for many in South Africa the arrival of his army only represented a disaster. Indeed, it represented a tragedy for many outside of South Africa too. A land of roughly 200,000 people doesn’t get conquered without producing many displaced people, especially when the invasions occur during a drought. Thus the Zulu warriors caused a refugee crisis that became known as the Mfecane (variously translated as “the scattering” or “the crushing”).

So many people were displaced that in their search for safe homes, many had to travel to such nations as modern day Zambia, which was more than 500 miles from their old homes in modern South Africa. Particularly desperate refugees made it all the way to Tanzania, which meant a journey of more than a thousand miles. The nations of Lesotho and Swaziland were created as improvised mutual protection pacts for refugees, and those tiny countries still exist today. The hardships the Mfecane caused extended even to the colonialists as the refugees would create fearsome new communities that gave them fierce military opposition, such as the Sotho and the Gaza of Mozambique. Throughout this turmoil starvation was so rife that some were forced to turn to cannibalism. However thrilling the history of war may be, there is almost always a tragic side to it.

Dustin Koski is also the author of Not Meant to Know, a dark fantasy novel about rogue exorcists.