There are many dubious claims about what might lie hidden in the Vatican Secret Archives – from alien remains and time travel devices to prophecies of impending Apocalypse – all of which position the Holy See as an implausibly powerful agent in the history and fate of mankind.

But a handful of historical documents made public by the Vatican really do show how much power the pope has wielded, and how influential his decisions have been – not just within Christendom but all over the world. Correspondence with heads of state, aspiring heads of state, and other important figures, as well as ancient records, papal bulls, and dogmas, all shine a light on the pivotal role of the pope. Here are 10 of the most intriguing.

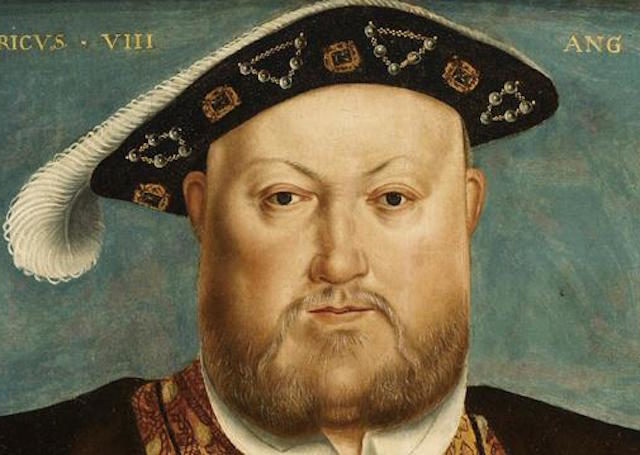

10. Henry VIII’s Request for Divorce

When Henry VIII wanted to divorce Catherine of Aragon so he could marry Anne Boleyn, he found himself mired in Vatican red tape. So he sent them some of his own: a petition signed by more than 80 clergymen and lords and appended with all of their seals – each dangling impressively from a row of scarlet ribbons.

The message was clear: If the pope refused to grant a divorce, England was poised to rebel. The manuscript was strongly worded too, threatening “extreme measures” should the king be denied his request. Clearly, he expected resistance. And that’s exactly what he got; Pope Clement VII’s response came back as an unequivocal “no.”

But what’s interesting about the king’s letter, discovered under a chair in 1927, is that it marked a major turning point in British history. In response to the pope’s refusal to grant the divorce, the country turned its back on the continent in a way that’s arguably echoed in Brexit today. The Church of England, or Anglicanism, re-allocated divine right to the king instead of the pope and set off a bitter religious feud that would rage for centuries afterward.

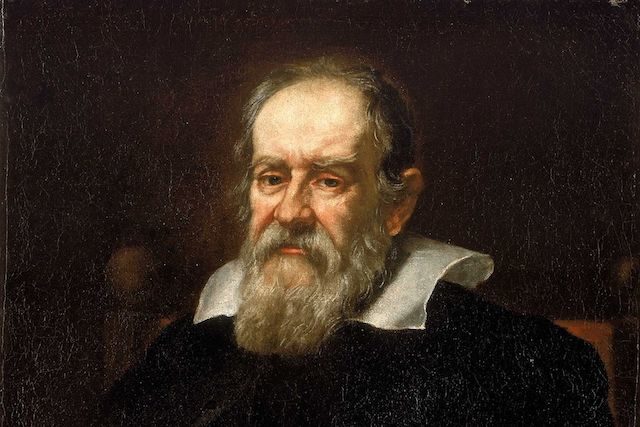

9. Transcripts from the Trial of Galileo

Famously hauled before the Inquisition in 1633, Galileo was rebuked (not for the first time) for the “absurd, philosophically false” proposition that the Earth orbits the Sun. But he wasn’t the only one working on the theory. Despite appearing to contradict bible passages in which the sun stops moving in the sky, the old Copernican theory was gaining traction within the Church. Even Pope Urban VIII, who ordered Galileo’s trial, had at one time praised him for his work.

However, the Church was going through a turbulent time, and it was now in the pope’s interests to make an example out of Galileo. For one thing, it sent a message to the astronomer’s patrons, the powerful Medicis, warning them not to take sides in the ongoing Thirty Years War. For another, it demonstrated to Urban VIII’s more conservative political critics that he was no radical thinker himself.

For many within the Church, though, a more fundamental concern was that Galileo was undermining Aristotelianism. They didn’t really care whether the Earth orbited the Sun or the Sun orbited the Earth; what mattered to them was upholding the validity of classical Greek logic, since it was upon this framework that Christian theology was based. If Aristotelian philosophy came apart, they feared, the whole Catholic system would go with it.

In the end, no doubt thanks to friends in high places, the Vatican settled for burning Galileo’s books in lieu of his body. He did, however, spend his final years under house arrest, and it wasn’t until 1992 that a pope finally apologized for the error.

8. Letter from the Pope to the Seventh Dalai Lama (1708-1757)

Showing the true extent of the Vatican’s global reach, even from relatively early on, is an 18th century letter sent by Clement XII to the seventh Dalai Lama. In it, the pope politely requests that a mission of European friars be allowed to preach in Tibet and, as such, the letter also represents an evolving attitude of interfaith tolerance within the Vatican.

On this occasion, however, the missionaries were overreaching. While they were initially welcomed by the Dalai Lama and even allowed to build a church, they were met with hostility in the end. Their decision to set themselves up in the capital ultimately proved too ambitious, since they stood a better chance “saving souls” among the relatively uneducated folk of the country.

The missionaries did manage to convert a small number of youngsters in Lhasa, but that only provoked conflict with the elders. In the end, the friars left Tibet for Nepal and were eventually forced to give up there as well. Clearly, they underestimated the deep conviction of Buddhists and Hindus, just as they had elsewhere – hence the limited spread of Catholicism in Asia, despite its unlimited reach.

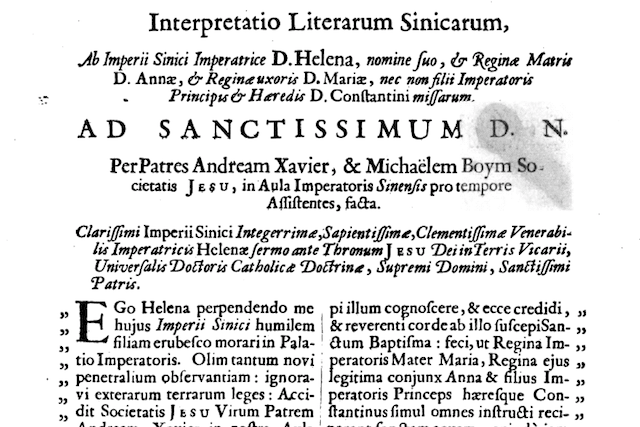

7. Letter from the Grand Empress Dowager Helena Wang

That said, not all Catholic missions to the Orient were so profoundly unsuccessful. In China, for instance, the Jesuits had been able to convert even the Grand Empress Dowager Wang to the faith, bestowing upon her the Christian name Helena in 1648. This conversion was actually part of a wider strategy to spread Christianity through China starting from the top.

The Jesuits were historically more organized than other missionary groups, and could be relied upon to carry out such plans. When Jesuit priest Andreas Koffler arrived in China through present-day Vietnam, several key figures of the Southern Ming dynasty had already been converted by his colleagues. And when Koffler converted the Grand Empress Dowager, a number of others followed – the Empress Dowager Ma (renamed Maria), the Empress Wang (renamed Anna), and the future Yongli Emperor himself (who was baptized and renamed Constantine).

Unfortunately for the Church, the rival Qing dynasty were relentless in their campaign to destroy the Yongli court, and the latter were forced into hiding. It was during this time that Helena personally wrote to Pope Innocent X. Her attractive letter – written on silk and scrolled inside a bamboo tube emblazoned with a black dragon – expressed her devotion to Jesus Christ and urged the pope to send more Jesuits into China. It also requested that he intercede with God on her behalf to ensure her family’s protection in exile. The letter was entrusted to a messenger who returned with it to Rome. However, by the time it reached the Vatican, Pope Innocent X was already dead. And by the time the messenger returned to China with a note from Pope Alexander, so were the Grand Empress Dowager and most of her court.

6. Papal Bull Splitting the New World in Two

In addition to venturing east, the Vatican set its sights west – dividing and distributing lands in the New World just as it had in the Old. Following Spain’s discovery of South America and the rivalry this provoked with Portugal, Pope Alexander VI issued a papal bull splitting the new land in two.

His “inter caetera” was drawn up in 1493 and was basically just a line between the North Pole and the South Pole “one hundred leagues” west of Cape Verde and the Azores. The pope declared that everything on the far side was Spanish and everything on the near side Portuguese. However, given that 100 leagues is only around 550 kilometers, and that the Azores and Cape Verde are much closer to Europe than America, it doesn’t take a map to realize how unfair this decision was. All Portugal got was Brazil, while Spain got everything else – even the Pacific Ocean. Moreover, the papal bull stipulated that anyone found trespassing on the Spanish side would be excommunicated and sent to Hell.

Unsurprisingly, Pope Alexander VI, a Borgia, was essentially just a puppet for Spain – not just Spanish himself but also in need of their support.

And that wasn’t the only thing that was unfair about this decision that shaped the world. The pope had also bestowed rights – almost orders, in fact – to overthrow the “barbarous nations” already established in the New World, to colonize, convert, and enslave the natives, in other words. Since the 1990s, those natives have campaigned to get it revoked.

5. Letter from Native American Ojibwe

400 years after calling for their subjugation, the Vatican was sent letters of thanks from Native Americans themselves. One of the Vatican Archives’ most unusual documents is an 1887 letter addressed to Pope Leo XIII from the Ojibwe tribe of Grassy Lake, Ontario. Written on birch bark, the letter addresses the pope as “the Great Master of Prayer,” and thanks him for sending a bishop their way.

Although written in the Ojibwe language, the letter was translated into French by the missionary, who also corrected the date. Instead of May, the Ojibwe had datelined the document: “where there is much grass, in the month of flowers.”

The Ojibwe, or Chippewa, are among the most numerous and widely distributed Native American populations, referring to themselves simply as “the people” (“anishinaabe”). While they and many other groups have adopted Christianity, they have also tended to indigenize it, fusing it with their own belief in “Great Spirit” Giche Manidoo.

4. The Doctrine of Immaculate Conception

The belief in the Immaculate Conception – that Mary gave birth to Jesus as a virgin, free of “original sin” – is fundamental to the Catholic faith. It underpins attitudes of purity, devotion, and grace, and exalts the mother of Christ as the impossible ideal of Christian femininity. In many countries, reverence for the Blessed Virgin even borders on idolatry.

So it’s surprising to find that Christ’s virgin birth wasn’t official Catholic doctrine until well into the mid-nineteenth century. Pope Pius IX only published the Apostolic Constitution of the Immaculate Conception in December 1854. Before this, the faithful weren’t bound to accept the dogma as true. Only now was it said to have come directly from God.

However, there’s a slight problem with this: there’s apparently no mention whatsoever of a virgin birth in the Bible. On the contrary, in Luke 1:47 Mary addresses God as her “savior,” implying that she was just as sinful as the rest of us.

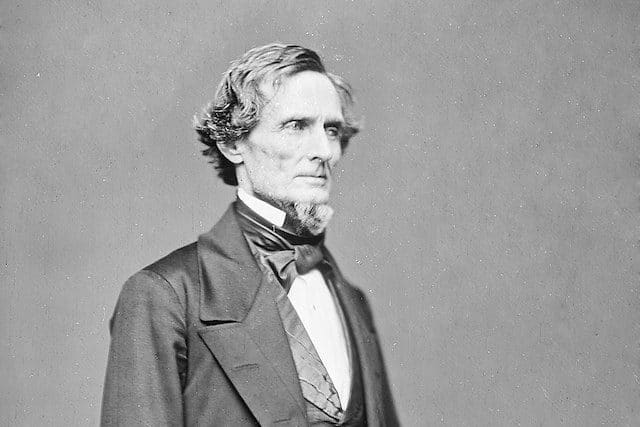

3. Letter from Pope Pius IX to the President of the Confederate States of America

During the American Civil War, Italy was in much the same state, split between those in favor of unification (the Piedmontese in the north) and those who were dead set against it (the Kingdom of Two Sicilies in the south).

Self-styled “Confederate President” Jefferson Davis therefore saw in Pope Pius IX a fellow victim of northern oppression and a potentially powerful ally. However, there was one crucial difference: while the conflict in Italy had much wider political motives than slavery, it was the northern Italians, not the southern, who objected to its abolition.

Nevertheless, Davis wrote to the besieged Vatican in the 1860s in a bid to forge diplomatic ties. Claiming to share the pope’s grief at the devastation the Civil War had caused, he stressed his authority as “President” to lead. And it came as a pleasant surprise for Davis (and a deeply unpleasant one for Lincoln) when Pius IX sent a letter back addressing him, in Latin, as the President of the Confederate States of America and expressing his desire that “America might again enjoy mutual peace and concord.”

Although the pope never explicitly supported Davis’s cause, this undoubtedly gave it a boost. General Robert E. Lee apparently idolized him for it, declaring Pius IX to be “the only sovereign … in Europe who recognized our poor Confederacy.”

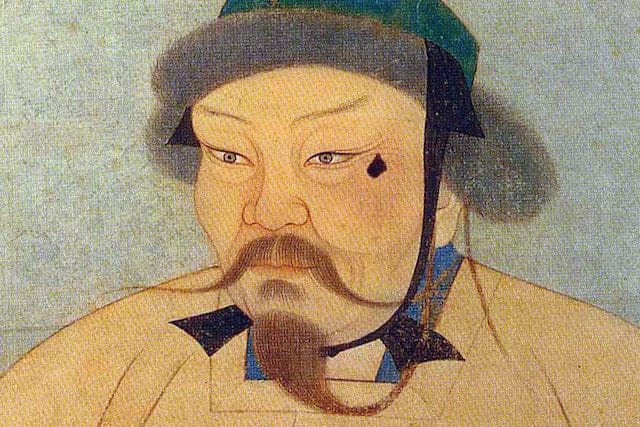

2. Letter to Genghis Khan’s Grandson

For all its worldly influence and wealth, the papacy met its match in the Mongols – at least in pomposity and hubris.

By the 13th century, having conquered China and overrun Persia, the Mongols were turning on Europe. Attacks launched against Christian countries by Ogedei, Genghis Khan’s son and successor, were on the rise and things were looking bleak. The Mongol horde appeared to be unstoppable.

When Ogedei died, however, the Mongols were brought to a halt. In accordance with tradition, they were all called back to the capital to decide on a suitable new leader. This unique window of opportunity gave Pope Innocent IV a chance to exercise his influence – or so he thought. Dispatching an elderly Italian friar on a donkey to intercede on his behalf, he hoped to save Christendom by rebuking the future Khan with a letter. This was in brazen contrast to the approach taken by other diplomats, who typically sent barrels overflowing with silver and gold.

While they were impressed enough by the friar’s journey to grant him an audience with the Khan, he was forced to wait four months before an actual response was forthcoming. The letter he eventually returned to Rome with, after two and a half years, was not at all what the pope was expecting. Addressed directly to Innocent IV, it asserted the divine right of the Grand Khan Guyuk (Genghis Khan‘s grandson) to rule the world. It also ordered the pontiff to come to Asia himself, with all of his kings, and pay homage in submission to the Mongols. Otherwise, the letter threatened, he would be considered an enemy.

1. Transcripts from the Trials of the Knights Templar

For more than 700 years, the Knights Templar have been tarnished by accusations of heresy. Obscure rumors abound of devil worship, sodomy, usury, and the possession of magical artifacts – including the Holy Grail, parts of the Cross, and even the Ark of the Covenant. But for much of the middle ages the Templars were highly respected, even revered.

Having been instrumental in conquering Jerusalem, for instance, they chaperoned pilgrims across it. They’re also said to have destroyed an army of 26,000 with only 500 men of their own, amassed a fortune from noble families, and become a key financier behind European monarchs and their wars.

So where did it all go wrong?

Somewhat surprisingly, it was Philip IV of France, and not the “infidel” Muslims, who hastened the Templars’ demise (though strategic losses in the Holy Land didn’t help). Heavily in debt to the order, the French king seized upon their decline as an opportunity to get out of paying them. Accusing the knights of heresy, he petitioned Pope Clement V to arrest them and put them to trial. And, since the pope was under French protection at the time, there was considerable pressure to do so.

The Chinon parchment, exhibited in 2007 after decades “lost in a drawer,” is the detailed, 60-meter transcript of the trials of the Knights Templar between 1307 and 1313. It lists a range of damning confessions, including treason, idolatry, homosexual “kissing rites,” and spitting or urinating on the Cross, among other charges dreamt up by the king.

But the transcripts also reveal a softer than previously thought verdict from the pope, who declared the order not to be heretical but merely immoral. While this might seem a trivial difference at first glance in canon law it meant the difference between excommunication and effectively a spiritual pardon.

Of course, they were burned at the stake either way, but it’s obvious why the Vatican has kept quiet. In the wake of the parchment’s exhibition, the Templars’ self-styled “heirs” tried to sue the Church for more than $150 billion — the estimated value of the assets wrongfully seized by Pope Clement V. These included crown jewels, thousands of estates, and several entire kingdoms. Of course, the claimants haven’t been able to retrieve any of it – but only because they’ve been unable to prove any blood relation to the order (for now at least).

5 Comments

Pingback: 10 of the Most Heavily Guarded Places on Earth - Toptenz.net

Oops! Thanks for the correction – I’ll rework it soon

Love to see Vatican archives referencing extraterrestrial presence on Earth.

Penelope Hernandez is correct. It would be amazing if the Vatican Library had anything about the immaculate conception being about Jesus since it is about Mary, not Jesus.

Ummm, the Catholic doctrine of the Immaculate Conception doesn’t refer at all to the birth of Jesus. The birth of Jesus is the Virgin Birth. The Immaculate Conception refers to Mary’s conception – that she was conceived without Original Sin. See https://www.catholic.com/tract/immaculate-conception-and-assumption