The Normans are best known today for conquering the Anglo-Saxons, who lived in modern-day England, in 1066 AD, under the leadership of William the Conqueror. The invasion didn’t just transform England; the effects are still felt around the world today.

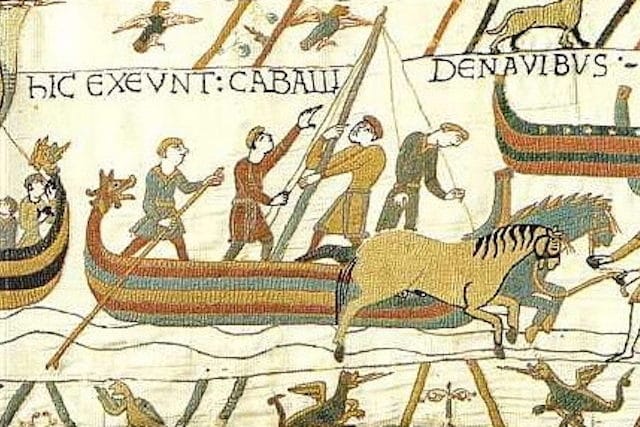

10. They Originated in France, But They Were Actually Vikings

One common misconception about the Normans is that they were French, but they were actually Vikings from Denmark, Norway, and Iceland.

During the 8th century, the Norsemen (Northmen) started to invade and plunder cities on the Northern coast of West Francia, which is modern-day France. By 900, they managed to get a foothold in the valley of the lower Seine River.

In 911, King Charles III of West Francia and the leader of the Normans, Rollo, signed a treaty granting the Vikings an area of land, which they called Normandy.

9. The English Conquest was Decided in Pretty Much a Day

The Norman Invasion of England happened in the wake of the death of the Anglo-Saxon King, Edward the Confessor, who died in 1066 without an heir to the throne. When he was alive, Edward promised the throne to two different men – his brother-in-law Harold Godwineson and William, Duke of Normandy.

When Edward died, Harold became King Harold II, and William wasn’t happy about this. However, William wasn’t the only person who wanted to be King of the Anglo-Saxons. Tostig, who was Harold II’s exiled brother, and Harald III Hardraade, King of Norway, both wanted to be king.

Tostig and Harald III separately invaded England and eventually teamed up. Harold II’s army was able to defeat them, but his forces were severely weakened and ill-prepared to take on the Normans. Harold II was killed on October 14, 1066, effectively signaling the defeat of the Anglo-Saxons.

8. William the Conqueror’s Coronation

William was to assume the throne of what would become England on Christmas Day 1066 at Westminster Abbey. Outside the Abbey, a large group of both Normans and Anglo-Saxons had amassed and tensions were high.

When the congregation inside the abbey shouted their approval of the new king, the guards standing just outside of the abbey thought that the noise was protests, so they acted rationally and checked on the commotion. No, not really. They started burning buildings near the abbey and riots ensued. Needless to say, William’s reign as the first Norman King was off to a great start.

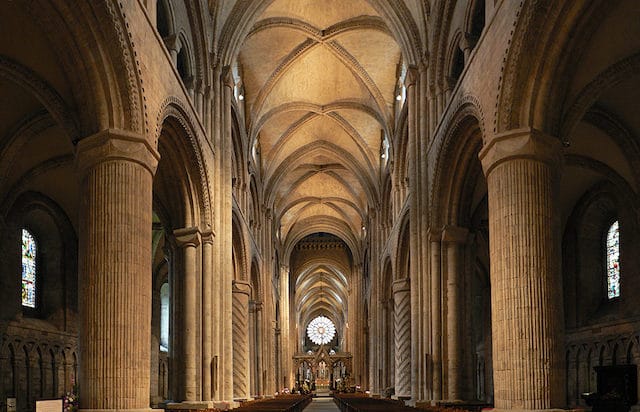

7. They Rebuilt Every Cathedral in England

One of the most astonishing things about medieval England are the beautiful cathedrals that are nearly a thousand years old. They are an amazing milestone in architecture and technology, and even centuries later, a lot of them are still standing.

Before 1066, there was only one Romanesque cathedral in England and William wanted to change that. First, he started to replace all the heads of the church, and then a short time later, he started to tear down nine of England’s 15 cathedrals which, in some cases, had been used since the days of the saints.

By 1135, under the reign of William the Conqueror’s son, Henry I, all 15 of England’s cathedrals had been replaced with Romanesque cathedrals. This includes Durham Cathedral (pictured above), Rochester Cathedral, and Ely Cathedral.

6. They Built the First Castles in England

Castles are an indelible part of medieval England. When thinking about that era, it’s hard not to envision them. Well, one reason that England has these classic castles is because of the Normans.

After invading England, William wanted the Anglo-Saxons and the Normans to live side-by-side peacefully. But the Anglo-Saxons weren’t exactly happy about being conquered and they didn’t like that their places of worship, which they had been using for centuries, were destroyed and replaced. Another problem facing the Normans is that they were vastly outnumbered. This unrest led to many English uprisings followed by violent Norman suppressions.

Looking to impose more law and order, William built the first castles in England. The first one was built for his family, and then he continued to build castles throughout England. Not only would they give the Norman knights a physically strong place to defend and sleep, but they were very symbolic. It was a visual reminder that the Normans were strong, and that they were to be feared.

Today, over 90 Norman castles remain standing.

5. The Conquest of Southern Italy Just Sort of Happened

In the first half of the 11th century, young Norman knights traveled to Southern Italy to work as mercenaries for the the Lombards and the Byzantine Empire. But when they got there, they realized there was a lot of room for personal advancement; they could even get their own fiefdom.

At the time, Southern Italy was populated mostly by Muslims, lacked a strong central government, and there was a lot of conflict between the states. The Norman knights, who were trained in warfare from a young age and were pretty unscrupulous when it came to their morals, realized that the lack of a central government and the constant conflict left a big power vacuum, which they tried to assume. Over the next three decades, there were wars between the Normans and the other states before the County of Sicily was established in 1071.

Norman Sicily was a very multicultural state, but it only lasted for about a century. In 1189, William II, King of Sicily passed away without an heir and the Norman stranglehold on Southern Italy faded away.

4. They Were Anti-Slavery

If you know anything about Viking culture, you probably know that they owned and sold slaves. Well, slavery was one of the big ways that the Normans differed from their Viking ancestors. In the early days of their civilization, the Normans used and sold slaves, but during the 9th century they started to adopt more Frankish customs, and the Franks didn’t use slaves. After the 9th century, there are no mention of slave markets in the writings in Normandy, and a passage written in the 1120s by William of Malmesbury suggests that slavery was a thing of the past, and looked down upon. He wrote:

They would purchase people from all over England and sell them off to Ireland in the hope of profit; and put up for sale maidservants after toying with them in bed and making them pregnant. You would have groaned to see the files of the wretches of people roped together, young people of both sexes, whose youth and beauty would have aroused the pity of barbarians, being put up for sale every day.

The leading theory as to why slavery was phased out by the Franks and the Normans is the rise of the knights, who had their own territories. This led to wars, but the knights learned that it was better to capture and ransom enemies than it was kill or enslave them. Also, around the same time the Peace of God movement was urging that non-combatants not be targeted. This led to less young men and women being captured after a war, so there simply weren’t many people to enslave.

When the Normans conquered England in 1066, they didn’t abolish slavery right away. An estimated 10 to 30 percent of the Anglo-Saxon population at the time were slaves, and to free that many slaves at once would have caused more damage. Instead, William installed his moral tutor, Lanfranc, as Archbishop of Canterbury and Lanfranc preached anti-slavery. In 1070, a law passed making it illegal to sell a slave to a foreign country. As a result, over the next 20 years, the population of slaves decreased and by 1120, it was almost entirely frowned upon within the culture.

3. The Harrying of the North

In the winter of 1069, William still hadn’t conquered all of England. Notably, Northern England still wasn’t under his control. At the time, William’s reign went no farther than York and the people of North England, called Northumbrians, were the biggest threat to William’s power and started a series of rebellions. They soon teamed up with some Danish warriors and planned on overthrowing William and the Normans.

Instead of taking on the combined forces, William approached the Danes and offered them gold and silver if they just packed up and left in the spring. The Danes agreed and then William went to work punishing the Northumbrians.

William split his army into teams and sent them into the area. Their goal was to kill all the rebels and destroy all their resources so they couldn’t rebel again. In total, the Norman knights managed to burn and destroy 100 miles of the area. They destroyed fields, livestock, and food supplies and as a result, many people were forced to eat cats, dogs, horses, and even human flesh.

Some estimates put the death toll of the Harrying of the North at tens of thousands of people. The massacre gave the Normans a reputation for being violent and cruel barbarians and while there were other small uprisings, no one tried another full-on rebellion against William the Conqueror.

2. William the Conqueror’s Death

In July 1087, at the Battle of Mantes in France, William the Conqueror was injured when he fell against the pommel of his saddle, severely injuring his intestines. He died five weeks later on September 9, 1087, in Rouen.

When it came time to bury him, they discovered that the stone sarcophagus they built for him was too small. So they were forced to stuff his bloated body into it, but when they pushed on his body, it caused one of his bowels to burst, emitting a terrible smell into the air. It was so bad that even people living in the Middle Ages noticed how terrible the smell was and the ceremony wrapped up pretty quickly after that.

Ah, William the Conqueror. The famed leader transformed England in life, and was the subject of what would be par for the course in an episode of South Park in death.

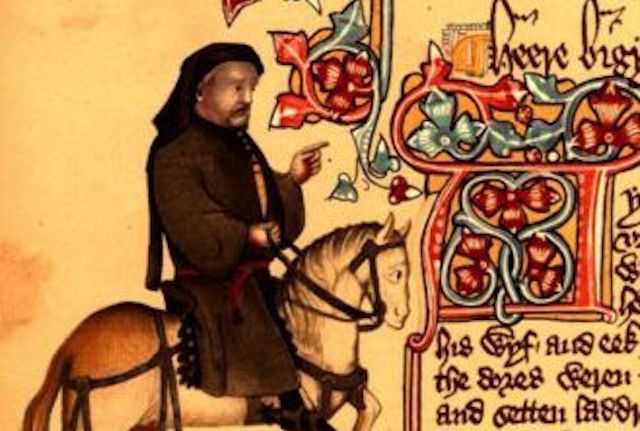

1. The Norman Influence on the English

Modern English owes a great deal to the Normans. Before the Norman Conquest, Anglo-Saxons spoke Old English. With the Norman influence, English grammar became simplified and added more synonyms. For example, someone can be hungry (English) or famished (French). It had such a profound effect that by 1150, the language had entered a new phase – Middle English.

The difference between Old English and Middle English is massive. For example, here is an excerpt from Beowulf that was written before the Norman Conquest:

HWÆT, WE GAR-DEna in geardagum,

þeodcyninga þrym gefrunon,

hu ða æþelingas ellen fremedon!

oft Scyld Scefing sceaþena þreatum,

monegum mægþum meodosetla ofteah,

egsode eorlas, syððanærest wearð

feasceaft funden; he þæs frofre gebad,

weox under wolcnum weorðmyndum þah,

And this is from “The Wife of Bath’s Tale,” which is part of Geoffrey’s Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales that was published in 1478:

Experience, though noon auctoritee

Were in this world, is right ynogh for me

To speke of wo that is in mariage;

For, lordynges, sith I twelve yeer was of age,

Thonked be God that is eterne on lyve,

Housbondes at chirche dore I have had fyve —

If I so ofte myghte have ywedded bee —

And alle were worthy men in hir degree

Sure, it’s not exactly as easy to read as J.K. Rowling, but it probably makes more sense than some text messages you’ve received.

Other Articles you Might Like