Protests can take many forms. They can be peaceful, or they can turn violent. They can be made up of just one individual, or they can comprise millions. Protests can happen in just one place, or simultaneously around the globe. They also take on a wide variety of names, depending mostly on what the issue is about and who is labeling them. For instance, what some may call a civil resistance in the face of an oppressive government, others say it’s an open disobedience movement. In the end, it’s all about perspective, isn’t it?

In any case, protests are always a sign of a long festering problem that needs to be addressed, either by the government or the institution it was aimed towards. And it will come as no surprise to know that there’ve been many protests over the years, all across the world. Now, even though the issues behind a protest are equally as complex as their outcomes and what they’ve managed to achieve in both the short and long term, here are 10 of the most important in human history, simplified.

Note: these protests are listed in chronological order

10. The Protestant Reformation

Before we start, it’s important to note that the word ‘Protestant’ contains the word ‘protest’ in it, similarly to how ‘Reformation’ has ‘reform’. Now, with that being said, most historians place the start of the Protestant Reformation in 1517 when a German monk and Professor of Theology by the name of Martin Luther nailed his “95 Theses” on the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg, Germany. But while this was common in the academic world at that time as a means to initiate debate, the theses were meant to simply protest some of the Church’s methods and to reform some of its practices. What they did, however, started a chain of events that changed Western Europe beyond recognition.

One of the reasons Luther was disappointed with the Church was its sale of indulgences. These were basically pieces of paper that were sold in exchange for the buyer spending a shorter time in Purgatory before his soul could enter Heaven. Another reason was that, in his view, God’s grace was freely given to anyone by faith alone, whereas the Church insisted that ‘good deeds’ like Church donations were needed. In any case, while the Church in Rome was slow to react at first to Luther and his reforms, others were more open to his ideas. Thanks to the printing press, his reforms caught on in many parts of Europe, in places like Germany, Scotland, Scandinavia, parts of France, Transylvania, and the Baltics.

Prior to the Reformation, the Catholic Church had great authority over Western and Northern Europe, both spiritually and politically. The Papacy controlled great wealth, lands and even armies. It formed alliances and rivalries, it waged war, and the level of corruption in Rome was notorious. With the arrival of Luther and his ideas, many European rulers saw an opportunity for the Church to loosen its grip on their kingdoms. This was the moment in time when the Church in Western Europe became divided and several other branches like Lutheranism, Calvinism, and Anglicanism, among others, came to be. The transition, however, was not smooth or peaceful. Countless wars and rebellions were fought over the coming decades, and during the Thirty Years War alone (1618-1648), Germany lost close to 40% of its entire population. Now, even though this was a particularly violent period in Europe, the Church Reformation did give a kick start to the Renaissance and the Scientific Revolution.

9. The Boston Tea Party

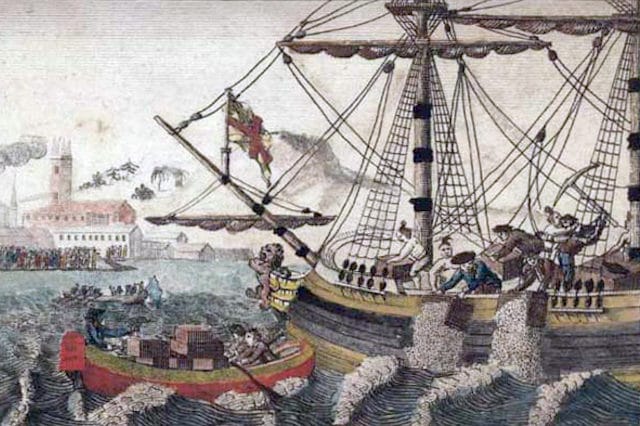

By 1773, the British Crown, as well as the English East India Company, an organization involved in trade with Asia and India, were having financial troubles. So, in order to rescue the company and continue profiting from its strategic position in India, the British Parliament decided to pass a new legislation over the American colonies, known as the Tea Act. This legislation imposed that only British tea could be purchased by the colonists, thus giving the East India Company a monopoly over those goods. Now, even though this tea was actually cheaper than what even smugglers could provide, the law didn’t go down well with the colonies, who said that taxation without representation was unconstitutional (even though, no, the US Constitution didn’t yet exist). The Tea Act also rekindled some previous disputes between the colonists and the British Crown over similar taxations in the past.

And while consignees in New York, Charleston, and Philadelphia rejected the tea shipments, the Boston merchants didn’t give in to the Patriots demands and received three British ships into its harbor. These ships contained over 90,000 pounds of tea, the equivalent of about one million dollars in today’s currency. As an act of defiance, on the night of December 16, 1773, Samuel Adams and the Sons of Liberty, disguised as Mohawk Indians, boarded the ships and dumped all 342 chests of tea into the water. The British Parliament saw this incident as an act of open rebellion towards the Crown and labeled Massachusetts as the core of all disobedience in the colonies. This led the British to retaliate and enact martial law by passing the Coercive Acts one year later, in 1774.

Among others, these acts enforced the closing of Boston Harbor until all the damages caused by the Boston Tea Party were paid for in full. They restricted Massachusetts from holding democratic town meetings, and British officials were immune to criminal prosecution. They also required the colonists to quarter British troops on demand, even in their private residences, if need be. The hope was that these legislations would cut Boston and New England off from the other colonies and stop them from forming a unified resistance against British rule. Instead, these laws backfired and led to the War for Independence.

8. The Storming of the Bastille

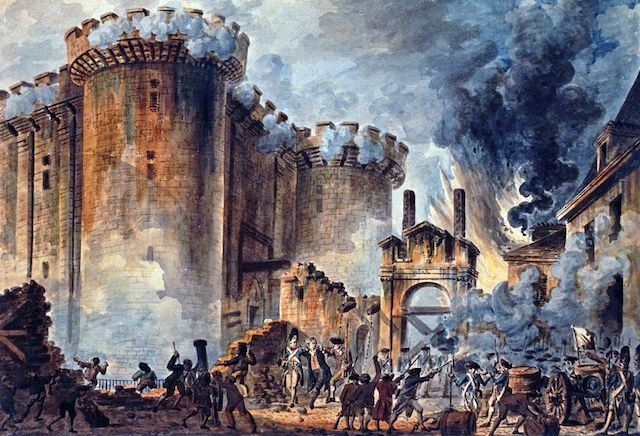

France, in the late 18th century, was going through a tough period in terms of politics, finances, and social stability. Tensions were running high as the monarchy and nobility were arguing over several unpopular tax reforms that tried to bring France out of bankruptcy. This, coupled with an ineffective ruler, Louis XVI, as well as the economic hardships endured by the French citizens, led the nation to descend into near chaos. As the country seemed to be headed towards a constitutional monarchy, many feared that the royal government would not relinquish its powers so easily. In the meantime, King Louis XVI had loyal troops surround Paris, something which the Parisians saw as an act on the king’s part to instill martial law and dismantle the national assembly. So, in order to prepare themselves accordingly, people started looting guns shops, small armories and even private collections. On the morning of July 14, 1789, a crowd of several thousand stormed the Hôtel des Invalides, a military infirmary that also had a large cache of almost 30,000 rifles and several artillery pieces. The problem was that there was no gunpowder or ammunition to load those weapons with.

The mob then travelled across Paris, to the Bastille, hearing that there were over 250 barrels of gunpowder inside. The Bastille was a fortress built in the centuries prior as a defense against the British. But since then, the Bastille was expanded and fortified, acting both as a royal armory and prison. Even though the fortress served the French crown in the past, it now held very little strategic importance. For the citizens of Paris, however, the Bastille symbolized the tyranny and everything that was wrong with the establishment. Though lightly guarded, Marquis de Launay, the Bastille’s governor, did not let the mob enter, and by mid-afternoon the fortress came under siege. Two detachments of the French Guard deserted and joined the rioters. After three hours, the guards surrendered and the Bastille was conquered. Marquis de Launay was also killed by the mob on his way to the courthouse to be judged.

Now, in the grand scheme of things, the storming of the Bastille had little political or military ramifications. It nevertheless signaled the beginning of the French Revolution and became a symbol of the end of the old regime. The French Revolution that followed triggered the end for many monarchies all around the world, most being replaced by republics or liberal democracies. It is regarded by many historians as one of the most important events in human history. July 14 is now France’s National Day, also known as Bastille Day.

7. Woman Suffrage Parade of 1913

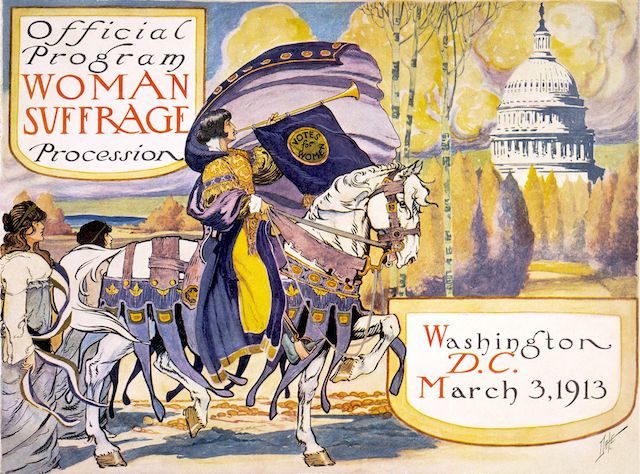

It’s almost hard to think that women in the United States did not have the right to vote as late as 1920. That’s less than 100 years, by the way. And it was no easy thing getting there, either. On March 3, 1913, however, the Woman Suffrage Movement was flung into the spotlight as over 5,000 women marched down Pennsylvania Ave in Washington DC, demanding their right to vote. To be fair, women had been battling with discrimination for at least 60 years prior to 1913, but only now were they able to have a major event of any national significance. The timing for the parade was wisely chosen too, as it was one day ahead of president-elect Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration. This meant that there were already many more people in Washington at the time – people who came to see the presidential event. This ensured a higher degree of press coverage for the Woman Suffrage Parade, as well as a higher degree of violence against them.

Besides the 5,000 marchers, the parade was made out of 20 floats, nine marching bands, four mounted brigades, as well as an allegorical play being performed near the Treasury Building. Leading the parade was lawyer and activist Inez Milholland, riding a white horse. The march was off to a good start until it went down Pennsylvania Ave and came across the thousands of people in town for the inauguration. As they were mostly men, the marchers began being ridiculed, tripped, and even assaulted. The police did very little to help, and in some cases, they even joined in the harassment. Luckily, boys from the University of Maryland formed a barrier to protect the women from the angry mob. In the end, over 100 women were hospitalized for injuries. The altercations also amplified the magnitude of the event and became a major news story across the country. The DC police superintendent also lost his job.

After the procession, suffragist Alice Paul made a statement by giving the parade as a symbolic example of how the government was systematically mistreating women – saying that this was a symptom of their lack of representation and political influence through the right to vote. Now, even though it took another seven years before the Constitution was amended in 1920, the Woman Suffrage Parade played a pivotal role in reinvigorating the suffrage movement.

6. Gandhi’s Salt March

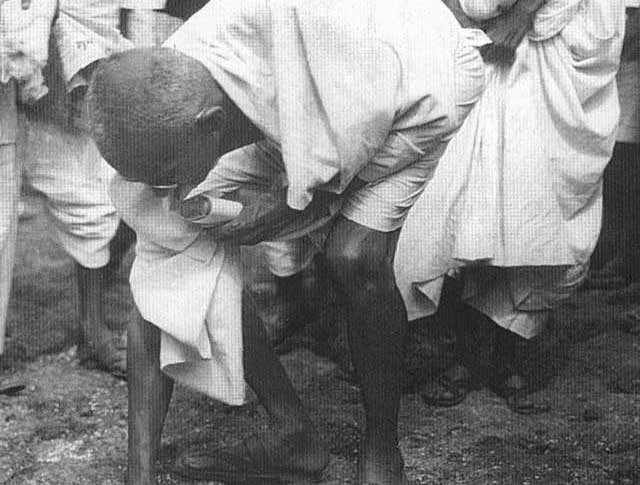

Indian people had a very difficult time under British rule, to say the least. And to rub salt into their wounds even further (pretty literally, in this case), the British even forbade the Indian population from producing or selling their own salt, and instead were ordered to buy it from their colonial masters. Now, even though salt production in India was a highly lucrative monopoly for the British for many years, they nevertheless forced the locals to buy it back at a very steep and highly taxed price. These Salt Acts put a heavy burden on a great majority of Indians who simply could not afford it, thus creating a high probability for dissent that was bubbling just below the surface. This is where Mahatma Gandhi comes in. As a student of law in London, he got his start as an activist in South Africa advocating for the right of Indians there. When he returned to India, he was committed to bring his country out from British rule.

He was ultimately successful in doing so by emphasizing the importance of non-violent protest to achieve a political goal. And one of his most celebrated protests was the Salt March of 1930. He set out on foot on March 12 from his religious retreat near Ahmadabad in western India and travelled to the town of Dandi on the Arabian Sea coast, some 240 miles away. The journey lasted for almost a month, with him stopping in towns and villages along the way and talking about the unfairness of the salt tax and his ideal of non-violence. And while he started off with a handful of companions, by the time they reached the coast, they were numbering in the tens of thousands. The plan was to work the salt flats on the beach and make salt, but the police heard of this plan and crushed the salt into the mud before they got there. Nevertheless, Gandhi reached down and picked up a lump of salt from the mud, thus breaking the British law.

The word spread like wildfire and soon enough millions of people joined in the protest all across India. Many people were beaten by the police and over 60,000 people were imprisoned, including Gandhi himself. The protests nevertheless continued without him over the following months. In January 1931, Gandhi was released from prison and a truce was subsequently declared. These protests inevitably set out a chain of events that led to India’s independence in 1947.

5. South Africa’s Defiance Campaign of 1952

The late 1940s and early 1950s were a particularly hard time for South Africa – especially for the majority of black citizens. After an unexpected election victory for the National Party in 1948, it immediately set out to restructure the social organization of the country by enacting the Apartheid laws, as well as to tighten the other, already existing discriminatory legislations and amendments. These laws not only sought to segregate the South African society by race in every way possible, even going as far as denying black people from entering cities, but also to deny them any political participation or representation at all levels of government. These new legislations made the African National Congress (ANC) abandon its previous moderate tactics of petitions and deputations, and instead opt for more militant actions such as boycotts, strikes, and open civil disobedience.

Then, on June 26, 1952, the ANC launched the Defiance Campaign, the largest such non-violent resistance in South Africa. For the first time in the country’s history, Africans, Indians, some Europeans, and other minorities were acting together for a joint political action and under the same leadership. Walter Sisulu was leader of the ANC and Nelson Mandela was the volunteer-in-chief who coordinated the campaign. Small groups of people all throughout the country, predominantly in the larger cities, then began to defy those discriminatory laws by entering forbidden areas without permission, sitting themselves in places reserved only for whites, or going outdoors after curfew. Over the following months, the movement gathered more momentum, leading to over 8,000 arrests by the end of the year. Though the penalties for disobedience were minor, with either short-term imprisonment or a fine, there were some cases of whippings, assault, or bad treatment, especially in the later parts of the campaign.

In the end, the Defiance Campaign wasn’t successful in achieving its goal of overturning the Apartheid laws, but it was able to draw the attention of the UN, which launched an investigation into the matter. The ANC also grew exponentially in number, reaching tens of thousands of members, and showing the government the potential power of African leadership in matters of organization and discipline. Walter Sisulu and Nelson Mandela were arrested several times and released. Once in 1956, then again in 1963, they were arrested and charged with treason, for which they received life in prison. They were released in 1989 and 1990, respectively, with Mandela becoming the first president of a democratic South Africa.

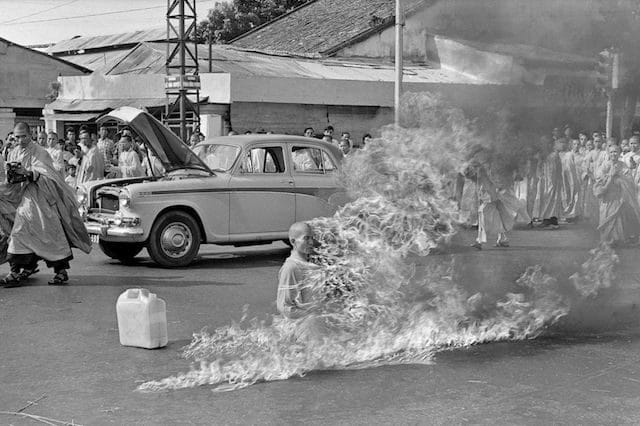

4. The Self-Immolation of Thich Quang Duc – 1963

On June 10, 1963, US reporters located in South Vietnam were being informed by telephone that during the following morning ‘something important’ was going to happen outside the Cambodian embassy in Saigon. And even though only a handful of correspondents actually showed up, surely enough, something big did happen. On the morning June 11, 350 Buddhist monks and nuns marched to the site, followed by a car. Then, a 65-year-old monk by the name of Thich Quang Duc emerged from that car, accompanied by two others. One of them then placed a small cushion in the middle of the street and Duc calmly sat down in the lotus position. The third monk brought a 5-gallon gas canister from the trunk, poured it over Duc’s head and moved away. Duc then rotated the prayer beads in his hand, said the words “homage to Amitabha Buddha,” lit a match, and set himself on fire. And while everyone was in shock over what was happening, Duc didn’t move or make a sound for the entire 10 minutes that followed. Malcolm Browne, the man who took the photo, won the Pulitzer Prize for it, with JFK saying that “No news picture in history has generated so much emotion around the world as that one.”

What happened on that day came as a response to the South Vietnamese government’s persecution of Buddhists in the country. Even though they made up the majority of the population, close to 90 percent, President Ngo Dinh Diem was pro-Catholic and highly discriminatory of Buddhists. Even after this gruesome event stirred uproar around the world, Diem didn’t stop his persecutions. In fact, he even went on to arrest more than 1,000 monks. As things were degenerating, other Buddhists followed in Duc’s steps by burning themselves alive too. This poor state of affairs ultimately led to a military coup that removed Diem from power via assassination on November 2, 1963. Duc’s actions also inspired several people in the United States to set themselves on fire while protesting the Vietnam War.

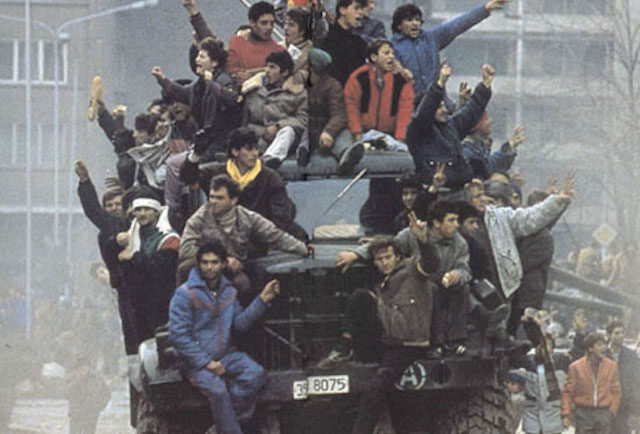

3. The 1989 Romanian Revolution

Also known as the Autumn of Nations, the tumultuous period in the second half of 1989 and early 1990 saw a wave of revolutions sweeping across the countries of Central and Eastern Europe that culminated with the removal of communism in the region, the fall of the Soviet Union, and the end of the Cold War two years later. The 1980s was a period of severe economic decline within the Soviet Union and in 1985, with the arrival of Mikhail Gorbachev to power, the nation began a shift toward the West and a greater degree of liberalization. These social and economic reforms began to slowly transfer to the other communist nations in Europe, but not all were so quick to change. Romania under Nicolae Ceausescu was one such nation.

Even though the dictator started his reign of power as an apparent reformer and a communist leader praised by the West for his willingness to stand up to Moscow, by the early ’80s he was well on his way in building his own cult of personality, inspired by North Korea’s Kim Il-sung. Starting in the late ’70s, he demolished a fifth of the capital’s old city center and began building grand boulevards, Soviet-style apartment buildings, and the People’s Palace – one of the largest buildings in the world. In 1981, he instilled a harsh austerity program over Romania with the intent of liquidating the country’s entire national debt. This meant an incredibly hard time for the Romanian people, with shortages in everything from food, to electricity, heating, or fuel. Coupled with the state’s infamous and brutal secret police (even by Soviet standards), the Securitate, Romanian citizens were obviously fed up.

The events that took place In Romania, in December 1989 were as quick as they were violent. Even though the other nations under the Iron Curtain had seen a largely peaceful transition from communism, Romania was the exception. On December 15, a Hungarian priest was imprisoned for offering sermons attacking the regime. This sparked uproar in Timisoara, a city in the west of the country. As a response, Ceausescu organized a rally on December 21 by gathering 100,000 people and hoping to give the impression of stability. This backfired, however, as the people started booing during his speech. Word quickly got around the country, mass protests began to spring up, and the army was called in to intervene and shooting the protesters. Ceausescu and his wife were taken away by helicopter while chaos ruled the streets of Bucharest. The following day, the army suddenly changed sides, captured the Ceausescus, and on Christmas Day they were given a mock trial and summarily executed.

2. The Tiananmen Square Protests of 1989

By the end of the 1980s, China was experiencing a sentiment of growing desire for social and economic reforms. To be fair, the country experienced a decade of great economic growth and a higher degree of liberalization, brought on by Hu Yaobang’s reforms. He had been the Chinese Communist Party’s general secretary since 1980, but was forced out by communist hard-liners in 1987. In mid-April, 1989, Hu died and tens of thousands of students gathered in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square demanding more democratic reforms. Over the following weeks the crowd grew to encompass people from all levels of society. The government’s first reaction was to issue stern warnings as more and more people began rallying in other cities throughout the country. Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev also made a visit to China in mid-May, bringing with him Western journalists, as well as bolstering the number of protesters in Tiananmen Square to about one million.

Fearing that the country would descend into chaos, the Chinese government issued martial law and ordered the military to disperse the protesters. The armed forces were stopped from reaching the square when the citizens of Beijing flooded the streets, halting their advance. But on the night of June 3, tanks and heavily armored troops descended on the square, firing at and rolling over all those who stood in their way. By morning, Tiananmen Square was cleared and by June 5, the military assumed complete control over the situation by violently suppressing protests in the other cities. In the aftermath, many people had lost their lives and thousands were imprisoned. Some protesters were even executed for their roles in the protests. But from the start, the Chinese government downplayed the whole incident, and in the years since, the government has attempted to suppress any talks about it. Any public mention or commemoration is banned by law, but residents of Hong Kong hold an annual vigil in memory of the incident.

1. The Iraq War Protests – 2003

2003 marked the start of the long and drawn out war in Iraq. It’s almost an impossibility for people to be unaware of this particular conflict and the ramifications it has had on society, even to this day. Little over a month before the war actually started, over 600 protests sprang up all across the world, opposing the conflict that was to come. In what was one of the largest organized protests in world history, the weekend of February 15-16, 2003, saw around 30 million people rallying in towns and cities all across the globe. Pacifist protests even sprang up in places like Cape Town, Dhaka, Havana, and Bangkok. Spain saw roughly 3 million protesters spread throughout the country, but mostly centered in Madrid and Barcelona. In London more than one million people gathered, and Rome became the Guinness record holder for the largest anti-war rally in history, with over three million people present.

Yet, despite these overwhelming numbers and the obvious public opposition against the war, it nevertheless started one month later, as if nothing happened, and with those millions of people’s pleas falling mostly on deaf ears. For instance, Australia’s Prime Minister said that “I don’t know that you can measure public opinion just by the number of people that turn up at demonstrations.” In Italy, on the other hand, Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi made no official comments about the march, but his deputy, the far-right leader of the National Alliance, Gianfranco Fini, called the protest “ideological anti-Americanism” and “totalitarian pacifism.” The events weren’t even broadcast live nationally, under the reasoning that it would put “undue pressure on politicians.”

Now, even though Tony Blair, George Bush’s strongest supporter in favor of the war said at the time that liberals were marching to defend a tyrant, he has more recently expressed his “sorrow, regret and apology” about what happened. In the vacuum left behind Saddam Hussein, various forces are still battling for control and influence even to this day, with ramifications that threaten world peace.

6 Comments

The 2003 Iraq war protests don’t even rank in the top ten protests of this century. They were meaningless and didn’t accomplish anything.

Pretty much my point. The whole question of whether the war was necessary or based on a lie is immaterial. The question for me – in an article that’s headlined as the 10 most important protests in human history – is whether the protests were the 10 most important in human history.

As you say, JLac, I’m not even sure they’re the 10 most important this century. Between the Tea Party protests, Occupy Wall Street, Antifa, Arab Spring, Women’s March, etc., I’d wager that any of those could have been chosen over a bunch of protests in 2003 that whine about Bush and accomplished nothing. Not to mention the WTO protests the year before the 2000’s began. In fact, I’d say that the 2003 protests weren’t really about the war at all – merely an excuse by leftists to protest a Republican President they didn’t like from day 1, and the result of those protests was… nothing. Bush was re-elected and the war didn’t stop.

This is a Top Ten and therefore subjectively selective. It is indeed sad that the 2003 protests achieved little. However, GW Bush’s utter disregard for the immense people protests against the Iraq War, and his willingness to lie to Congress in order to fulfill his objectives by a totally unnecessary shock and awe war against the Iraqi people, has regrettably gone totally and unjustifiably unpunished. This because of the USA’s diplomatic power, and its unwillingness to submit to the International Criminal Court. Saddam was a bad man, of this there is no doubt, but he was holding Iraq together. Now look at the mess of misery and destruction that Bush initiated. Where is the justice in this, and where is God whenever needed to take out the baddies?

How about the Tea Party protests of 2010? Formed as a reaction to an aggressive leftist agenda and resulted in the complete weakening of Obama’s Presidency?

Or the Berlin Wall protests that led to the collapse?

The protests of MLK, Jr.?

Surely any of these are more significant than the Iraq War protests that ended up accomplishing absolutely nothing.

Well, if anything, that particular protest showed that oligarchy is masked as freedom and democracy in the Western World. A sort of ‘illiberal democracy’, if you will.

This was debated between the author and myself when he first presented the idea. I think I agree with you that we could have chosen more monumental protests.