Since the first modern homo sapiens emerged some 50,000 years ago, it’s estimated that 107 billion human beings have at one time or another lived on planet Earth. The overwhelmingly vast majority of these people have been forgotten by history, but there are a very few individuals whose names and achievements will echo through the ages.

From ancient Greece through to the modern world, these are 10 of history’s greatest minds.

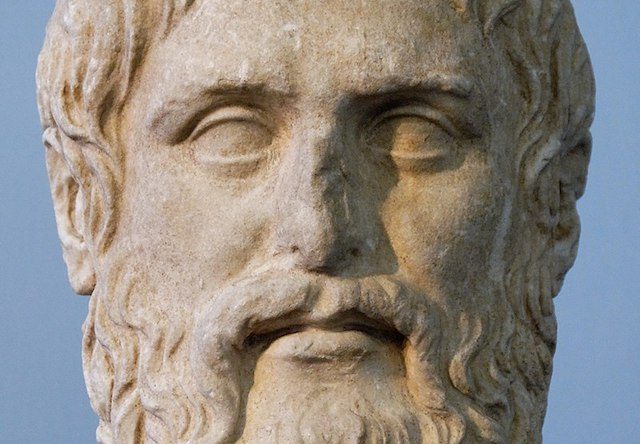

10. Plato (Circa 428 BC – 348 BC)

The philosopher Alfred North Whitehead once wrote that European philosophy is best characterized as a series of footnotes to Plato. While this might perhaps be something of a stretch, it gives an indication of the esteem in which the ancient Greek philosopher is held even to this day.

Plato’s efforts to understand the world around him covered metaphysics, ethics, politics, aesthetics, perception, and the nature of knowledge itself. Despite having been written more than two-thousand years ago, his work remains eminently readable today. Plato didn’t deal in dry, tedious treatise. He preferred to bring his work to life, teasing out thoughts and ideas in the form of a dialogue between characters. This in itself was a remarkably innovative approach. Plato blurred the lines between philosophy and entertainment and challenged the reader to scrutinize their own beliefs.

Having been born into one of the wealthiest families in Athens, Plato would have been well-schooled by the city’s finest philosophers. There’s no question it was his mentor Socrates who made the greatest impression, appearing again and again as chief protagonist in Plato’s dialogues. Socrates’ resurrection in immortal literary form would no doubt have been particularly galling to certain influential Athenians who had only recently killed him off. Ancient Greece was similar to the modern world in at least one respect: not everybody reacted kindly to having their beliefs challenged.

9. Leonardo da Vinci (1452 – 1519)

Born out of wedlock, and with no formal education, the young da Vinci seemed destined for a life of anonymous drudgery. In Renaissance Italy there was little social mobility. The right family name and connections were invaluable. Da Vinci had neither, but he was not a man who would blend into the background to be forgotten by history.

Flamboyantly dressed, a strict vegetarian, enormously physically strong, and rumored to be gay in an age when homosexuality could be punished by death, it was nonetheless the workings of da Vinci’s remarkable mind that truly set him apart.

In an age renowned for producing an abundance of great artists, da Vinci is regarded as one of the greatest of them all. Yet painting was by no means his only talent, nor perhaps even his greatest talent. He studied geometry, mathematics, anatomy, botany, architecture, sculpture, and designed weapons of war for the kings, princes, and barons who struggled for wealth and power in Italy’s warring city states.

It was as a visionary that da Vinci was arguably at his most brilliant. In an age when Europe lacked basics such as indoor plumbing, he sketched out designs for magnificent flying machines and armored vehicles powered by hand-turned crankshafts, ideas that were centuries ahead of their time.

In 2002, almost 500 years after his death, one of Leonardo’s visions was lifted from the pages of his notebooks to become a reality. A recreation of a glider based on his sketches, albeit with a few modifications deemed necessary to reduce the risk of killing the pilot, was successfully flown by World Hang Gliding and Paragliding Champion Robbie Whittall.

8. William Shakespeare (1564 – 1616)

The famous bard has become such an integral part of Western culture that it’s tempting to assume we must know a great deal about his life, but the reality is quite the opposite. He was certainly born in Stratford-upon-Avon, England, but the exact date is a matter of some conjecture. There are huge swathes of time where he disappears from the records; we have no idea where he was or what he was doing. It’s not even entirely certain what he looked like. The popular image of Shakespeare is based on three main portraits. Two of these were produced years after his death and the other probably isn’t a depiction of Shakespeare at all.

While history leaves us largely in the dark as to Shakespeare the man, almost his entire body of work (so far as we know) has been preserved. The best of his offerings are widely regarded to be amongst the finest, if not the finest, works of literature in the English language. He was equally adept at comedy or tragedy, had a gift for writing strong female characters, and possessed an intimate understanding of the human condition that imbued his work with a timeless, eminently quotable quality.

Shakespeare was by no means the only famous playwright of his era, but his work has stood the test of time in a way that others have not. Few people are now familiar with the plays of Ben Johnson or Christopher Marlowe; fewer still have seen them performed. While his rivals are now little more than historical footnotes, Shakespeare is even more famous and celebrated in death than he was in life. With an estimated 4 billion copies of his work having been sold, he ranks as the best-selling fiction author of all time.

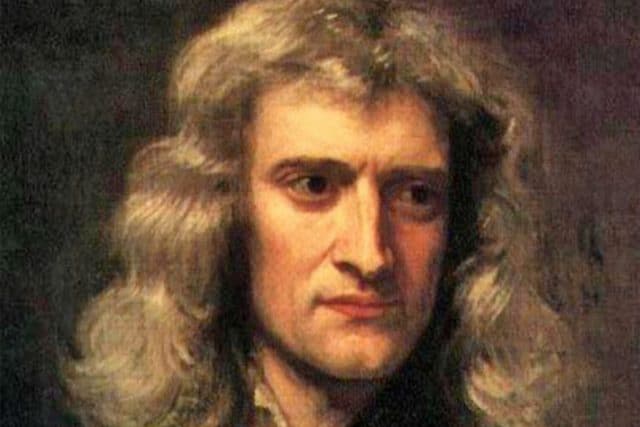

7. Isaac Newton (1642 – 1727)

In December 2016, a first edition copy of Isaac Newton’s Principia Mathematica sold at auction for $3.7 million. This was an extraordinary amount of money, but then Principia was an extraordinary book.

First published in 1687, Principia laid out the mathematical principles underpinning motion and gravity. It revolutionized science and was hailed as a work of near unparalleled genius, at least by the very few individuals capable of understanding it. Newton didn’t enjoy being questioned by lesser minds (which included just about everybody), so he wilfully set out to make Principia as difficult to follow as possible. To make it less accessible still, he wrote it in Latin.

If Principia had been Newton’s only achievement, then that would have been more than enough to earn him the title of scientific genius. But Newton did a great deal else besides. With a ferocious work ethic that drove him to at least two nervous breakdowns, he scarcely slept, never married, and often became so absorbed in his work that he simply forgot to eat or teach his classes.

In an astonishingly productive 30-year period Newton invented calculus (but didn’t bother to tell anybody), conducted groundbreaking work on optics, invented the most effective telescope the world had ever seen, and discovered generalized binomial theorem.

When Newton died in 1727, his collection of notes amounted to some 10 million words. This window to the mind of one of history’s greatest geniuses proved less useful than might be imagined. Newton was obsessed with alchemy, and the latter part of his career was consumed in a futile attempt to transmute base metals into gold.

6. Benjamin Franklin (1706 – 1790)

At the age of 12, Benjamin Franklin was made apprentice to his elder brother James at his printing business in Boston. What he lacked in formal education, the younger Franklin more than made up for in curiosity and intelligence. He soon surpassed his brother as both a writer and a printer, a fact that didn’t escape James, who regularly expressed his displeasure with his fists.

The terms of Franklin’s apprenticeship meant that he couldn’t expect to receive wages until he turned 21. Backing himself to do rather better on his own, at 17 he ran away to find his own fortune. He succeeded in spectacular fashion and would go on to become one of the wealthiest men in America.

While Franklin’s genius for business earned him a huge amount of money, this was never his overriding goal. Convinced that an individual’s entrance to heaven would depend on what they had done rather than what they believed, he was passionate about improving the lot of his fellow man. Amongst his many achievements he set up America’s first lending library, founded a college that would go on to become the University of Pennsylvania, and created a volunteer fire fighting organization.

Franklin’s talents as a businessman were matched by his brilliance as a writer, a mathematician, an inventor, a scientist, and a good deal else besides. Perhaps his most significant discovery was that lightning bolts could be understood as a natural phenomenon rather than as an expression of the wrath of an angry God. By understanding lightning Franklin was able to tame it. The principles of the lightning rod he developed to protect buildings, ships, and other structures from lightning strikes are largely unchanged to this day. In true Franklin form he preferred to freely share his invention rather than apply for a patent that would have been worth an untold fortune.

5. Ludwig van Beethoven (1770 – 1827)

Johan Van Beethoven was a man with a singular mission in life: to transform his son from a talented amateur into a musical genius to rival even the great Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. He would pursue this goal with ruthless, single-minded determination.

As a result, the young Ludwig van Beethoven’s childhood was rather a miserable affair. Forced to practice for hours on end, his father would loom over him ready to administer a beating for the slightest mistake. This punishing regime left no time to spare for fun or playing with friends. Witnesses reported seeing Beethoven perched on a piano stool at all hours of day and night. Even his education was cut short; at the age of 11 he was withdrawn from school to concentrate on music to the exclusion of all else.

It’s sometimes said that it takes 10,000 hours of practice to master a craft, and Beethoven would have exceeded this total from a very young age. His lopsided education meant that he struggled with simple mathematical principles throughout his life, but he became a truly phenomenal musician.

Beethoven ranks as arguably the greatest composer who ever lived, a feat which is all-the-more impressive since by the age of 26 he had developed a ringing in his ears. Over the next 20 years his hearing deteriorated to the point where he was totally deaf. Despite this considerable handicap, Beethoven’s intricate knowledge of music allowed him to produce some of his greatest works at a time when he couldn’t hear the notes he hit on his piano.

4. Nikola Tesla (1856 – 1943)

In 1884 a Serb by the name of Nikola Tesla set foot on American soil for the first time. He arrived in New York with little more than the clothes on his back, the design for an electric motor, and a letter of introduction addressed to Thomas Edison.

Tesla and Edison were both geniuses, both brilliant inventors, and between them they knew more about electricity than anyone else alive. However, there was one major problem. Tesla’s electrical motor was designed to run on alternating current. Meanwhile, a good deal of Edison’s income was derived from the Edison Electric Light Company, which relied on direct current.

In an attempt to protect his investments, Edison set out to discredit Tesla and convince the public of the dangers of alternating current. One particularly gruesome film, shot by the Edison Manufacturing Company, shows an unfortunate elephant by the name of Topsy being enveloped by smoke and keeling over after being blasted with 6,600 volts of electricity.

Despite these dirty tricks, Tesla’s system had one very significant advantage: alternating current could be transmitted over long distances, while direct current could not. Tesla won the war of the currents.

Tesla’s inventions, from hydroelectric power plants to remote control vehicles, helped to usher in the modern age, but he had no spark for business. In 1916, with his mental health deteriorating alarmingly, he was declared bankrupt. Afraid of human hair, round objects, and preferring the company of pigeons over people, he seemed to have become the embodiment of the idea of a mad scientist. This impression was only strengthened by Tesla’s obsession with developing a “death ray” capable of shooting bolts of lightning. Tesla believed his death ray would bring about an end to warfare, but he never succeeded in completing it. He died alone in a hotel room at the age of 86.

3. Marie Curie (1867 – 1934)

In 1896 the physicist Henri Becquerel made the serendipitous discovery that uranium salts emitted rays of some kind. While this struck him as rather curious, he wasn’t convinced that further research into the phenomenon represented the best use of his time. He instead tasked his most talented student, Marie Curie, with discovering just what was going on.

It wasn’t often that such opportunities fell so easily into Curie’s lap. In her native Poland there had been no official higher education available for females, so Curie had enrolled in a clandestine “Flying University.” On emigrating to France she had graduated at the top of her class, despite having arrived armed with only a rudimentary grasp of the French language.

Curie, working alongside her husband Pierre, identified two new elements, polonium and radium, and proved that certain types of rocks gave off vast quantities of energy without changing in any discernible way. This remarkable discovery earned Curie the first of her two Nobel Prizes, and it could have made her very rich indeed had she chosen to patent her work rather than make the fruits of her research freely available. It was widely assumed that something as seemingly miraculous as radiation must be hugely beneficial to human health, and radium found its way into all manner of consumer products from toothpaste to paint.

Even Curie had no idea that radiation might be dangerous, and years of handling radium very likely led to the leukimia that claimed her life in 1934. Her notebooks are still so infused with radiation that they will remain potentially deadly for another 1,500 years; anybody willing to run the risk of reading them is required to don protective gear and sign a liability waiver.

2. Hugh Everett (1930 – 1982)

By the age of just 12, Hugh Everett was already brilliant enough to be regularly exchanging letters with Albert Einstein. The American excelled at chemistry and mathematics, but it was in physics, and more specifically quantum mechanics, that he made his mark with one of the strangest scientific theories of the Twentieth Century.

Nils Bohr once famously wrote that anybody who isn’t shocked by quantum mechanics hasn’t understood it. The behavior of protons and electrons on a quantum level is downright weird, but Everett suggested it all made sense if there were an infinite number of universes.

Everett’s multiverse theory proved popular amongst science fiction writers, but it was derided by the scientific community. Disappointed, Everett largely gave up on quantum mechanics. He instead undertook research for the US military, attempting to minimize American casualties in the event of a nuclear war.

A heavy-drinker and a chain-smoker, Everett died in 1982 at the age of 51. Since then his ideas have begun to edge towards the scientific mainstream, and they do resolve a number of thorny problems. The universe operates to the laws of a set of numbers known as fundamental constants, and every one of these has to be precisely tuned in order for the universe to function as it does.

It seems that either humanity has been fantastically lucky, on the level of one individual winning the lottery every week for several months, or the universe has been intelligently designed. Everett’s multiverse theory suggests another possibility. If there are an infinite number of universes, then an infinite number of possibilities are played out. In such circumstances it comes as no surprise that we find ourselves in a universe that appears to be tuned to perfection.

1. Albert Einstein (1879 – 1955)

Contrary to popular belief Einstein didn’t fail math at school. He excelled at the subject, having mastered differential and integral calculus by the age of 15. However, while the spark of genius was already present, it would be quite some time until anybody recognized it. It’s fair to say that the academic world wasn’t beating a path to Einstein’s door. Having been rejected for a university teaching position, and then having been turned down by a high school, in 1902 the German-born physicist began work in the Patents Office in Bern, Switzerland.

The idea that a lowly patents clerk would go on to become arguably the most influential scientist of all-time would have appeared absurd, but in 1905, in what must rank as the most extraordinarily productive 12 months of individual intellectual endeavor in history, he produced four papers that would revolutionize the way the universe is understood.

In just one year he proved the existence of atoms, described the photoelectric effect, demonstrated that an object’s mass is an expression of the energy it contains (E = mc2), and published his Special Theory of Relativity. He would eventually expand the latter into his famous General Theory of Relativity, which suggested that space and time were one and the same thing.

Einstein’s theory of relativity was still just a theory, and one that was considered little short of heresy by a significant portion of the scientific community (Nikola Tesla included). It wasn’t until 1919, when his predictions on the behavior of starlight during a solar eclipse were demonstrated to be accurate, thereby proving his theory to be correct, that he was catapulted to international fame.