There are a total of 573 dead languages in the world, at least that we know of. A language can die off for a variety of reasons including political persecution, globalization, and poor preservation of vulnerable or critically endangered languages.

Classical Latin dissolved into more common languages as the Roman Empire dissolved, resulting in the Romantic Languages of Europe: Spanish, Portuguese, French, Italian, and Romanian. Mandarin rules most of China, save for the trade cities like Hong Kong, where Cantonese spreads rapidly. Similarly, over the last few decades in the UK, Cornish has been slowly overtaken by English.

From Ancient Egyptian to Sumerian, here are 10 languages the world has simply forgotten…

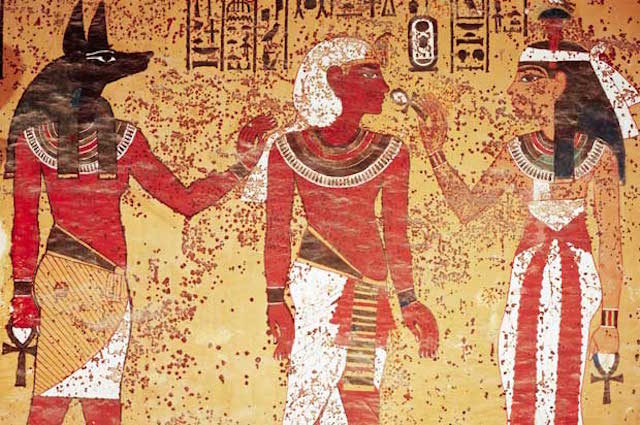

10. Ancient Egyptian

Ancient Egyptian is a dead language originating from the Nile valley. It’s a member of the Afro-Asiatic phylum and the language as a whole (including its modern forms) is actually divided into five separate periods: Old Egyptian, Middle Egyptian, Late Egyptian, the Demotic phase, and the Coptic phase with the last two phases taking place in the current era. It is also a combination of a logographic system with phonetic elements, where symbols represent words and phonetic signs can be translated to one of three consonants.

Some of the most famous pyramid texts were written during the Old Egyptian period, but most of the early writings from that period were actually just names and shorter inscriptions. This version of the language first appeared around 3000 BCE and lasted until around 2200 BCE.

What’s intriguing about the languages spoken during these periods is that they greatly differed from the written form of Ancient Egyptian that archaeologists find inscribed on all manner of walls and objects throughout the region.

9. The Xiongnu Language

The Xiongnu language was spoken by a nomadic people who lived throughout Central Asia, what is considered to be modern-day China and Mongolia.

Most of the information on this dead language comes from Chinese sources and, surprisingly, there is little translated directly from Xiongnu itself. Instead, most of the language is from Chinese transliterations, and even then, only a handful of titles and a single spoken sentence are available today, and only in Chinese documents.

It might come as no surprise, then, that there is no general consensus on Xiongnu as a language. Some scholars argue that it is a Turkish language, while others like Paul Pelliot have insisted that the language actually descends from Mongolia instead.

There are also archaeological sites in Yinshan and Helanshan that contain petroglyphs and cave paintings. Scholars like Ma Liqing suggest that these are the only true written forms of the Xiongnu language.

8. Ba-Shu

The dead language known as Ba-Shu today is actually the language spoken by two different peoples who lived in the East and West of the Sichuan Basin. The Ba people are known to have occupied the Jianghan Plain, which is near the place where the Yangtze and Han rivers meet. Where these rivers meet is where the Ba and Shu peoples fought many battles during the warring states period.

When the Qin Dynasty was established, the Ba people were annexed and with the backing of the Qin, their armies went forth and conquered the Shu. Later, during the Yuan Dynasty, the Sichuan province was mainly comprised of a Ba and Shu administrative unit.

Ba-Shu, or Old Szechwanese, is actually descended from Old Chinese and was one of the languages to split off from it. The Ba-Shu people that made up the Sichuan province were destroyed by the Han Dynasty of China, its people fleeing from their genocidal wrath.

The language, however, would finally die out during the Ming Dynasty, as it was overtaken by Southwestern Mandarin.

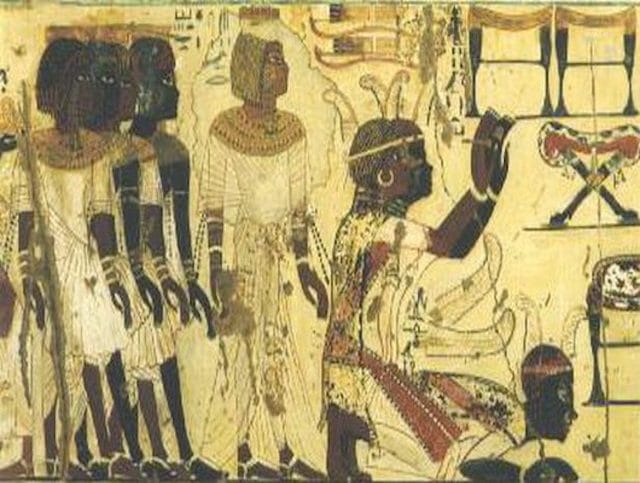

7. Ancient Nubian

Old Nubian is one of the oldest known African languages. Its existence was first written about by Italian scholars in the 8th and 15th century CE and refers to the language spoken by the people who lived in the Nuba Hills, and along the banks of the Nile River. Today, the descendants of this language are spoken in Sudan and southern Egypt.

Documents written in Old Nubian dating back to the 8th through 14th century appear to be primarily translations of Christian texts that were originally written in Greek.

In fact, where Old Nubian was used, both Coptic and Greek were used in some religious proceedings. But with the arrival of Islam, Old Nubian was all but abandoned in writing, as with the written form of Greek.

And the language would remain out of sight and mind until it was rediscovered in the 1980s by professor, Mukhtar Khalil Mukhtar Kabara.

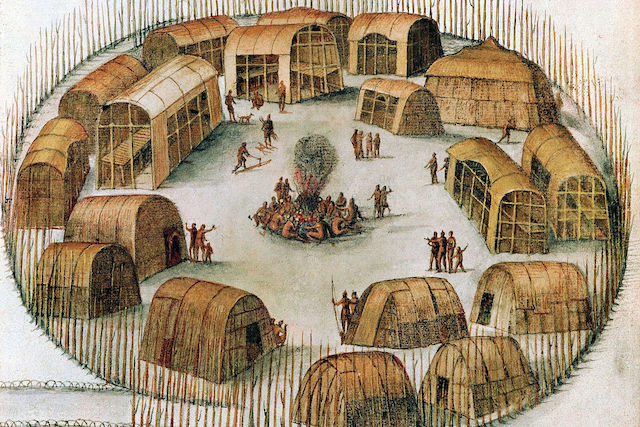

6. Algonquian–Basque pidgin

A pidgin language is one that develops between two groups who do not have a language in common. Its grammar is simple and to the point, drawing from multiple languages at once. The Algonquian-Basque pidgin language was used by the Mi’kmaq, Innu, and other Native American tribes who wished to communicate with European and French settlers in what is now known as Red Bay in Canada.

Algonquian-Basque pidgin vocabulary takes words from the Micmac, Innu, and Basque languages, as well as some words from Gascon (a romantic language spoken in southern France at the time). The Basques established as many as nine fishing villages, some able to hold up to 900 people, in Newfoundland and Labrador.

While the Basques occupied these parts of Canada in the early 14th century, it wasn’t until the 1530’s that the pidgin language was first spoken, and evidence of its use persists until the early 1700s, though the golden age is considered to last from 1580 to around 1635 CE.

5. Greenlandic Norse

Around 75% of Greenland is covered in ice, making it particularly indomitable for anyone looking to settle down and make it their permanent home. Even today, the population of Greenland has not exceeded 60,000 people, which says quite a bit considering its surface area equals around 1,350,000 square kilometers.

But in the late 980s in the Current Era, Norse Vikings did just that, which either made them brave or plain crazy (though it’s probably safe to say if one was a Viking in that age, it was probably a bit of both).

But the Vikings were not the first people to arrive in Greenland, as it had long been settled by the Innuit who had spread out from Alaska.

In the settlements created by the Norse Vikings, they spoke an old variant of the Norse language. This language would persist until these settlements were wiped out in the 15th century, but evidence in the way of runic inscriptions can still be found today.

4. Chicomuceltec

Chicomuceltec was a language spoken by the Mayan people in the municipalities of Chicomuselo, Mazapa de Madero, and Amatenango de la Frontera in Chiapas in Mexico. It was also spoken in some parts of Guatemala.

Unlike other languages on this list, this particular one managed to remain in use until the 1970s and 1980s until finally going extinct. Surveys at the time found that of the 1500 people who descend from the Chicomucelteco people spoke Spanish as their primary language.

Chicomuceltec was first reported on in 1894 by geographer Carl Sapper. While in Chicomucelo, he recorded 169 words, noting that they bore striking resemblance to the Huaxtect and northern Vera Cruz than any of the other Mayan languages he’d come into contact with.

But even in 1894, it was difficult for Carl Sapper to find native speakers of the language. Subsequent surveys in 1924 by Franz Termer would yield even worse results, with only 3 speakers of the language, but even into the 1970s and 1980s did rumors persist that native speakers of the language still exist in some parts of Chicomucelo, though none were ever found.

3. Tonkawa

The Tonkawa were a nomadic hunting tribe of Native Americans who lived near what is known today as San Antonio, Texas. They’re remembered today for their tradition of hunting buffalo, extensive burial rites, and their now-extinct language.

The Tonkawa language is what’s known as an isolate, meaning that it has no known related dialects or languages. Today, the Tonkawa people are English speakers, so it’s unlikely that there are any fluent in Tonkawa.

The language may indicate that the Tonkawa people migrated to Texas from the northern plains, but, unfortunately, the last native speaker of the language buried the only evidence of it in a fit of grief (and who could blame them). The tapes of the Tonkawa language remain lost, and other things like dances and songs have also been lost to time.

Though there may be some hope, as descendants of the Tonkawa people have been organizing in an effort to reclaim their lost heritage, and hopefully, revive or recover their lost language.

2. The Akkadian Language

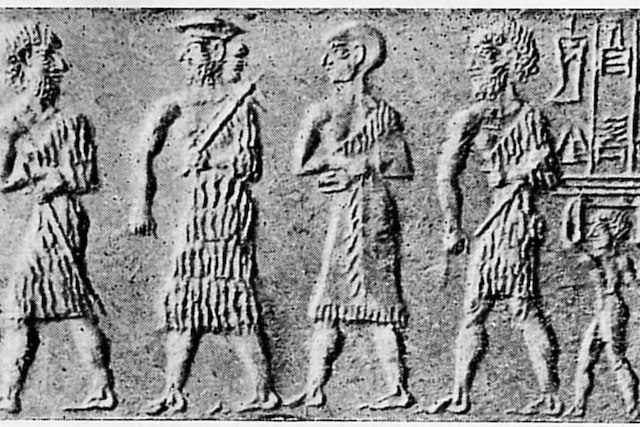

The Akkadian Empire dominated Mesopotamia, succeeding the Sumerians and replacing their language.

Akkadian is part of a group of East Semitic dialects that were spoken in Mesopotamia in 2800 BCE to 500 CE. Akkadian names were the first mention of the language in ancient Sumerian texts. Additionally, the language’s cuneiform script was taken from its Sumerian counterpart around 2350 BCE, and as such many Sumerian words were adapted into the new language.

Sumerian’s transition into Akkadian is often compared to how Chinese logographic writing was adapted into Japanese. Similar to this evolution of Japanese, Akkadian was polysyllabic, while Sumerian and Chinese were not.

While Akkadian remained the dominant language throughout Mesopotamia during the Empire’s rule, it did begin to evolve into the Assyrian and Babylonian dialects (spoken in the north and south of the region respectively). Babylonian would go on to replace Akkadian, completing this process by the 9th century BCE.

1. Sumerian

The Sumerian language was originally spoken in Southern Mesopotamia before the 2nd millennium. It was first attested to in 3100 BCE and would be replaced by Semitic Akkadian in 2000 BCE.

Sumerian is a language isolate, though some scholars do think that it could be related to Uralic languages like Hungarian and Finish, there is very little evidence to prove this. In fact, there is little evidence for how the Sumerian people arrived in Mesopotamia in the first place, let alone how their language developed.

Before the development of Sumerian literature, most of what we have to go on are administrative texts and wordlists meant to educate potential scribes. During the third Early Dynastic period, though, around 2500 BCE, we get the Kesh Temple Hymn, the Instructions of Shuruppak, and the predecessor of the Epic of Gilgamesh, Lugalbanda and Ninsun. This represented the culture breaking off from practical concepts like economy, administrative power, and responsibility, to embracing concepts like mythology and cosmology.

Although the Sumerian language was replaced officially by Akkadian, it actually remained in use for sacred ceremonies and texts. In fact, it survived almost as long as Akkadian did, only finally dying out shortly before the beginning of the Christian era.