Think of how long ago it was that the Western Roman Empire fell in the 5th Century AD. That’s nearly 1,600 years, more than 50 generations as understood by historians. Few nations from that time are still around today, major religions didn’t exist yet, and so on. Now consider that it’s roughly the same amount of time between the reign of Alexander the Great in the 4th Century BC, before the Roman Empire began, and the time of the Akkadian Warriors.

They’re not the most famous empire despite their pedigree as, among other things, creating the first full-time professional armies. Their most famous leader, Sargon of Akkad, certainly didn’t conquer a vast empire compared to Genghis Khan or the aforementioned Alexander the Great. Yet what we can see of this army through the work of teams of archaeologists paints a picture of a people who lived fascinating military lives…

10. Carving Out an Empire

2334 BC marked the year that the city of Akkad (also spelled Agade) was set on a course from being merely one city-state of many to one of the most important communities in ancient history. That was the year that Sargon took the throne and began a career of vast conquest. First, he conquered cities of the Elamites (modern day Iranians). His conquests then shifted to reach into modern day Syria and even far up into modern Turkey.

At least equally impressive as Sargon’s ability to conquer a staggering 34 cities was his ability to keep his empire intact for the length of his 56-year reign. Despite not being particularly tyrannical or hated in general, there were many rebellions for him to crush under his heel over the years, especially early on. One of Sargon’s techniques was to forgo appointments over personal connections and administrators based on merit. Sargon also had the foresight to have the walls of any city he conquered as thoroughly demolished as he could, which left them both easier to reconquer and more vulnerable to attackers outside the Akkadian Empire, and thus more reliant on Sargon’s soldiers. There were also such innovations put in place as private mail and steady trade routes to motivate cities to stay in the empire.

9. Conquest Motivations

The Akkadian Empire was not only the first major empire of the Bronze Age — bronze itself was a major contributing factor in getting those soldiers motivated to conquer Northern Mesopotamia. Bronze was useful both for making more durable weapons and farming tools.The combination of copper and tin was one of the few available alloys which could be sharpened to razor sharpness.

Metallurgy had been refined even in the 24th Century BC, and had reached a point where bronze weapons could be extensively decorated. The amount and elaborateness of inlays in a blade or hilt quickly became a status symbol. Women, meanwhile, were left with their jewelry, which often included silver from mines Sargon had conquered in Anatolia (modern day Turkey).

8. Weapon Advantage

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gfS-bnoRahA

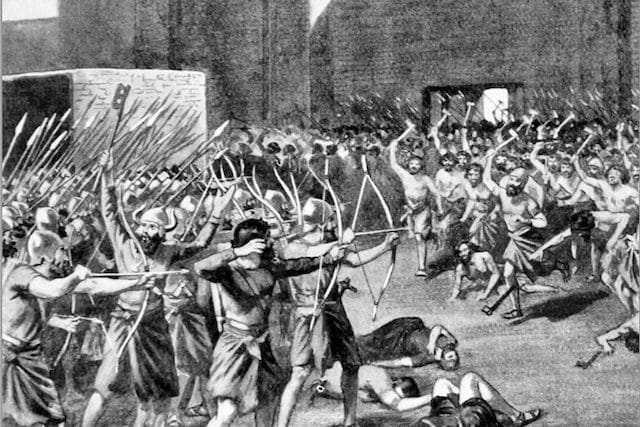

Beyond their cache of bronze armaments, early on the Akkadians acquired another instrument of war that proved to be a super-weapon for the time: composite bows. Essentially, composite bows differed from regular models in that when unstrung they curved away from the archer’s body, meaning the string was drawn tauter to function. This additional sturdiness came from the bow’s wooden shaft being supplemented by horn and wound sinew.

Against the arrows of the Akkadian archers, the leather armor favored by many of their foes was vulnerable. The range of Akkadian archers also expanded to roughly double that of their enemy archers. That meant 600 feet versus the usual 300-foot range their opponents could manage. That increase in range might not seem so devastating, considering that troops running at a charge could cover that extra 300 feet in maybe 15 seconds unencumbered. That would still be time for an average archer to fire two aimed shots, which could make all the difference. Additionally, it was invaluable for sieges if the Akkadians’ enemies were to be drawn out into the open.

7. The King from the People

It does not sufficiently convey how far he ascended to say that Sargon of Akkad was not of royal birth. It’s not even sufficient to say he came from a common family. He was, in fact, a bastard birth. His parents took drastic steps to conceal that he’d ever been born, stopping just short of actually killing him. He was placed in river rushes in a basket sealed with tar, later to be found and adopted by the royal gardner Akki. The strong resemblance this account bears to the beginning of the story of Moses is likely not a coincidence, as the date of Sargon’s birth is alleged to have preceded that of Moses by almost a millennium.

With a connection inside the palace, Sargon was able to rise through the ranks until he had the second most prominent and respected position: King Ur-Zababa of Kish’s cupbearer. In fact, despite his lowly-sounding title, his duties including managing Ur-Zababa’s invaluable wine supply, and he was generally regarded as second only to the king. However, Ur-Zababa eventually grew suspicious of his cupbearer. When the Sumerian king Lugalzagesi marched on Kish, Ur-Zababa sent Sargon with a peace offer. Concealed with the peace offer was a request for Lugalzagesi to kill Sargon. In another parallel with the Bible, King David was said to have done something similar to Uriah the Hittite so that the king could marry his wife Bathsheba. Instead of killing the messenger he had no known grudge against, Lugalzagei invited Sargon to join him, and the two marched on Kish and drove the Ur-Zababa out.

For reasons not explained very well by surviving accounts, Sargon was able to raise an army of his own and then marched on Kish. He defeated Lugalzagesi in battle, took the city, and declared himself King. Indeed, Sargon was not actually his birth name, but a title meaning “True-King.” Despite this grandiose title, Sargon’s humble beginnings gave him a populist appeal that helped him keep his empire together and put an administration and bureaucracy in place composed of functionaries chosen on the basis of merit.

6. Relatively Small Army

For someone so well-known today and who conquered such a large empire, it should be noted that the Akkadian Army created by Sargon was not particularly vast. Surviving records put it at 5,400 troops, stating that was the number which would “eat with” Sargon. For comparison, Egyptian pharaohs such as Ramesses II fielded armies of as many as 20,000 soldiers for their conquests.

Sargon divided his main army group into nine battalions, and further divided those battalions into groups of 60. Each of these battalions would be divided into regular infantry, archers, and light infantry called the “nim,” presumably a ribbing nickname since that translates to “flies.” The wealthiest soldiers were likely to be found riding in chariots. Troops on horseback wouldn’t be recorded in the Middle East until centuries after the Akkadian Empire, by which time horses had been bred which were large enough to serve as reliable mounts.

5. Helmet Horn Pioneers

In recent years it’s become a popular piece of trivia that there’s no evidence that Vikings wore helmets with horns or wings on them during the height of their raids between the 9th and 11th centuries AD. Fans of that fashion choice should know that Akkadian Warriors actually had bull horns attached to their helmets. They were the first recorded soldiers to adopt that style. It wasn’t meant as a symbol of intimidation so much as a supposed sign of their divinity.

While Sargon looms large over the Akkadian Dynasty, this is one innovation that he can’t lay claim to. The practice of putting horns on their helmets started with Naram-Sin, Sargon’s grandson and the first king in all of Mesopotamia to declare himself a God, hence the need for a divine helmet. As immodest as that declaration was, he was at least able to back it up by raising the empire to its largest size, greatest wealth, and highest level of development. The practice would continue for centuries after the end of Akkadian dominance, including being used by a race known as the Sardinians during their war against the Egyptians.

4. Land Holdings

Sargon needed to motivate his regular army to hold them together, but there was only so much wealth to distribute reliably at the time. So the Akkadian government adopted a policy called Ilkum. Sargon would essentially issue land to his subjects, and if they didn’t serve in his military or send their children as substitutes, then he would repossess the land. It was one of several ways that the Akkadian Empire was an early example of a “planned economy.”

Landowning soldiers were allowed to rent out their land. It’s unclear if that meant that their tenants could be sent to military service as substitutes. Ilkum was so effective that it was written into the famous Babylonian laws known as Hammurabi’s code and prefigured European and Asian feudalism.

3. The War of 33 Kings

As successful as Sargon and Naram-Sin were at keeping cities united in their empire, it was the man who ruled between them, Manishtushu, who might have been the best at uniting people. Inconveniently for him, it was uniting his enemies to take a stand against him. The Akkadian Dynasty had been known for decades as a force no one city-state could take on, so during his reign Manishtushu’s soldiers found themselves facing an alliance of a staggering 32 kings of city-states.

It must be said that Manishtushu was hardly the victim here, as he faced this alliance because he sent his army across what is known today as the Persian Gulf for greater conquest. More importantly, as far as history in general is concerned, the Akkadian army was triumphant over the course of his 15 year reign despite Manishtushu’s death in battle. Their prize was a rich haul of more silver mines.

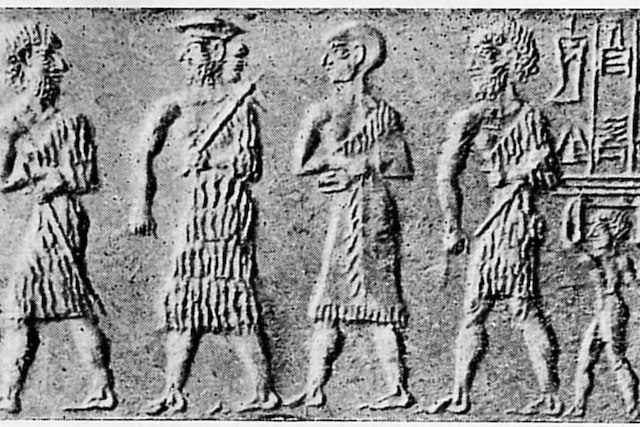

2. Naked Enemies

One of the most elaborate artifacts of the Akkadian Dynasty was a stele (i.e. a stone slab with a scene carved into it) for Naram-Sin, which stands about 79 inches tall. It depicts the grandson of Sargon as a giant standing over defeated enemies equipped with a horned helmet and composite bow, truly trademarks of the Akkadian Empire. One enemy at his feet is begging for mercy while another has been impaled on a spear. On levels farther below are corpses of other enemies while Naram-Sin’s soldiers are arrayed in formation. The fallen enemies have a distinct lack of clothing in common.

For a long time, historians believed that the nudity was because the scene in question was meant to depict ceremonial sacrifices. More recent studies have concluded that it was only a form of mockery of their opponents. Even the impaled man, presumably some sort of noble if he’s at Naram-Sin’s feet on the stele instead of among the piles of dead, is dressed in a mere Akkadian equivalent of a kilt. Only the defeated king of the Lullubi was sufficiently respected to be depicted fully dressed while begging for his life.

1. The Mysterious Conqueror

After a century of domination of Mesopotamia and beyond, the question arises of what caused the Akkadian Empire’s downfall circa 2154 BC. The dominant theory was that between widespread revolts and invasions by enemies, particularly the Gutian race, it was essentially war. However, later scientific analysis put forward climate change as the knife in the dynasty’s heart.

During Sargon and his immediate successors’ great conquests there was a prolonged period of unusually beneficial weather that resulted in good crop yields, which left the people content and sufficiently healthy for war. By the time Shar-Kalli-Saree took the throne, the region was struck with a drought. Trade was disrupted, discontent and desperation were widespread, and the empire couldn’t stand against its own citizens that had become refugees, let alone against enemy invasion. So severe was the drought that one city, Tell Leilan, was said to have been buried in a meter of sand as it was abandoned, and it remained abandoned for over 300 years. For millennia the memory of the Akkadian Dynasty fell into the shadow of the Sumerian and Babylonian empires that rose in its wake, only being rediscovered in 1867 AD in the ruins of the Library of Ashurbanipal in Nineveh.

Dustin Koski wrote the urban fantasy novel Not Meant to Know.