The year 1816 was the first since the onset of the French Revolutionary Wars in which the western world was at peace. In Europe, the nightmare of the Napoleonic Wars began to fade. In North America, Washington DC began the process of rebuilding after being burned by the British Army during the War of 1812. Global commerce was expected to thrive, unimpeded by the raiding ships of nations locked in a death grip with each other. Farmers expected strong markets for their crops, shippers looked forward to record profits, manufacturers hoped the return of peace would create demand for their products. But then a funny thing happened. There was no summer. As late as August of that year, hard freezes in the farmlands of upper New York and New England destroyed what little crops had been planted during a spring of continuous snow and freezing weather.

1816 was the year of no summer, not just in North America, but across the Northern Hemisphere. Record cold, freezing rains, floods, and frosts occurred throughout the months in which warmer weather could be reasonably expected, given centuries of its showing up more or less on schedule. It did not, and without global communication to understand why, the underpinnings of civilization – farming and trade – suffered across the globe. The year with no summer is now understood to have been the result of a series of geological events which masked the sun with volcanic dust, but to those who endured it, it was simply an inexplicable disaster. The commercial effects continued to be felt for years, as financial markets roiled from the unexpected disruption of trade and investment. For those unconcerned with climate change it remains a stark, though wholly ignored, warning of the power of nature. Here are just a few of its impacts.

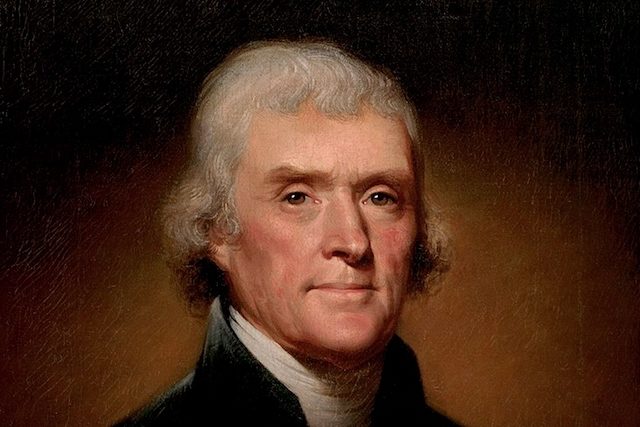

10. Thomas Jefferson found his indebtedness increased by drastic crop failures

In 1815 former president Thomas Jefferson, living in retirement at his Monticello estate, offered his personal library as replacement for the losses suffered by the Library of Congress when the British burned the American capital. The sale was a gesture which gained Jefferson some temporary praise, but more importantly to him it provided an infusion of badly needed money. The former president was broke, and the $23,950 (almost $400,000 today) he received alleviated some, but by no means all, of his indebtedness. Jefferson was relying on a strong crop from his Virginia farms in 1816 to reduce his debts further. In his Farm Book for 1816 Jefferson noted the unusual cold as early as May; “repeated frosts have killed the early fruits and the crops of tobacco and wheat will be poor,” he wrote.

Jefferson struggled with the bizarre weather throughout the summer months, recording temperature and rainfall data still used by scientists studying the phenomenon, but he was unaware of its cause. He did lament its effect. Jefferson’s corn and wheat crops were reduced by two thirds, his tobacco even more so, and the former president slipped yet more deeply into debt, as did most of the farmers of the American states of Virginia, Maryland, Kentucky, Tennessee, and all of New York and New England. The failure of tobacco crops was particularly devastating, ships which normally would have carried the cured leaves to Europe lay idle, and British tobacconists shifted to plantations in Africa as the source of the weed, in high demand in Europe. During the summer, Jefferson reported frosts in every month of the year in the higher elevations of Virginia, and in every state north of his farms.

9. Prices of grains spiked as the summer went on, and remained high for nearly three years

In Virginia, oats were a crop which was considered essential to the survival of the economy. Oats were consumed by humans in the form of porridge, and in oat breads and cakes, but the grain was also an essential part of the diet of horses. Horses were of course critical in the early 19th century as motive power for plows and transportation. The shortage of oats caused the farmers who produced it to respond to the insatiable demand for the grain by raising their prices on the little they were able to harvest. According to Jefferson and other Virginia farmers, oats cost roughly 12 cents per bushel in 1815, a price already inflated by the demand placed on the crops by the recently ended War of 1812, when armies needed horses for cavalry and as draft animals.

By midsummer of 1816, oats had increased to nearly $1 per bushel, an increase which most were unable to pay. The shortage of grain, (as well as other fodder) meant what horses were available were often undernourished. European markets were unable to make up the shortage, as Europe too was locked in the grip of the low temperatures and excessive rains. In Europe the cost of maintaining horses increased dramatically, and the use of horseback for individual travel became the privilege of the wealthy few. A German tinkerer and inventor by the name of Karl Drais began experimenting with a device consisting of a piece of wood equipped with a seat upon which a person would perch while moving the legs in a manner similar to walking. Called variously the velocipede, the laufmaschine, and the draisine, it was the precursor for what is now known as the bicycle.

8. Temperatures throughout the Northern Hemisphere were abnormally cold, especially in New England

The New England states were particularly hard hit during the summer of 1816 by abnormally low temperatures. In the New England states, which were at the time still mostly agricultural, every month of the year suffered at least one hard frost, devastating crops in the fields and the fruit trees which had managed to blossom during the long and wet spring. On June 6, a Plymouth, Connecticut clockmaker noted in his diary that six inches of snow had fallen overnight, and he was forced to wear heavy mittens and his greatcoat during his customary walk to his shop. Sheep were a product of many New England farms, well adapted to grazing on the hillsides in pastures too small to accommodate cattle herds. Shorn in late winter, as was customary, many died in the unexpected cold, and the price of lamb and mutton reached record highs.

By the end of June, temperatures in New England had begun a rollercoaster ride which they would retain for the rest of the summer, further damaging crops and livestock. Late June in western Massachusetts saw temperatures reach 101 degrees only to plummet to the 30s over the Fourth of July. Men went about in their hayfields harvesting their sparse yields dressed in overcoats. Beans – long a staple crop of New England – froze in the fields. From Puritan pulpits across the region, the weather was attributed to a righteous judgment of God. In August there was measurable snowfall in Vermont, and though winter wheat crops yielded some harvests, the cost of moving the grain to market was often prohibitive. New Englanders, especially in the rural areas, began to forage off the land in the manner of their ancestors, surviving on what game and wild plants they could find in the woods.

7. The lack of summer provided one of literature’s most infamous characters

Most people had no idea what were the scientific reasons behind the bizarre weather in the summer months of 1816. Many of the wealthy, better able to weather the storm, so to speak, went about their business despite the adverse weather conditions. In Europe, a group of young English writers and their guests summered at Lake Geneva, Switzerland. The group included Lord Byron and an English poet named Percy Shelley, who brought with him his wife, the former Mary Wollstonecraft. Housebound by the continuing inclement weather (Mary later wrote that it was an ungenial summer), the group was forced to find ways to entertain themselves. Bored of playing parlor games one of the members, probably Lord Byron, suggested that each member of the group write a story, along the lines of a ghost story, for the entertainment of the rest.

Mrs. Shelley at first balked at the idea, unable to come up with a plot until mid-July, when she confided to her diary that at the group’s nightly discussions she arrived at the idea of “Perhaps a corpse could be reanimated.” She began writing a short story, which grew into a full length gothic novel which she entitled, “Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus.” Her husband was later credited with assisting Mary with the work, though the extent of his contributions to the classic tale of horror remains disputed by scholars. Mary Shelley later credited her inspiration to a waking dream which came upon her during one of her long walks in the woods around Geneva, immersed in the gloom of the strange weather that summer. Shelley wrote that while her husband Percy – who committed suicide in 1822 – helped her with technical aspects of the writing, the tale wholly originated with her.

6. The year with no summer coincided with the end of the Little Ice Age

The year without summer is commonly ascribed to the summer months of 1816, though its effects were felt for three years, part of the final months of what is known as the Little Ice Age. Crop failures were acute in the first harvest season of the period, and such continued for at least another two years. Wet and cold weather impeded planting in the spring as well as harvests in the fall, and the size of the harvests from North America to China were insufficient to support the populations. Hunger became famine in many areas, including Europe and China, residents of rural communities migrated to urban areas in search of food through begging, and population density grew those diseases which strengthen among hungry populations, including cholera and typhus. Medicine of the time was inadequate to treat either.

The result was a globally felt – at least in the Northern Hemisphere – calamity, which encompassed starvation, diseases, and popular unrest for a period of three years. Hundreds of thousands of former soldiers, veterans of the Napoleonic Wars, roamed Europe seeking the means to feed themselves and their families. In England sailors who had manned the ships of His Majesty’s Navy found themselves unemployed as warships were decommissioned, and the absence of crops reduced the amount of goods available for international trade. Ships rotted at their moorings. By the summer of 1817 organized groups of former soldiers across Europe were rioting in the belief that government warehouses held grain being kept from the starving people. In the United States, especially in still largely agricultural New England, failed crops caused farmers to pull up stakes and head for the promised lands west of the Ohio River.

5. The Swiss disaster of 1816-1817 was among the worst of the global catastrophe

Over a period of 153 days between April and September, 1816, Geneva, Switzerland recorded 130 days of rain. The temperature remained too cold for the snow in the Alps to melt, which prevented the disaster from being far worse. The streets, and more importantly the sewers and drains, of Geneva were flooded, and Lake Geneva was too swollen with rain to absorb the runoff. Meanwhile local crops were drowned by the incessant chill rains, and the harvest of 1816 was a complete failure, leading to the last recorded famine on the European continent. The lack of fodder led to the demise of hundreds of thousands of draft animals and cattle and oxen died in the waters in the fields and alongside the Swiss roads. Hundreds of thousands of Swiss were rendered homeless, living in the streets and fields unable to feed themselves, as the brutal cold of an Alpine winter settled upon them.

Beginning in early 1817 the death rate in Switzerland, already well above normal due to starvation and disease, increased by more than 50%. Oxen, horses, and cattle dead from starvation and rotting in the fields became sources of food for the desperate populace. Aid from European neighbors was nonexistent, as the harvests on the continent and in England were similarly sparse. France had but recently survived its revolution and the ravages of the Napoleonic Era, it was short of manpower, and its newly restored monarchy was inadequate to the challenges of the disaster which had befallen. As the seemingly unending winter lengthened it soon became obvious to the people of Europe that those of wealth and privilege were better able to cope, and that the burden of suffering was being borne by the urban and rural poor.

4. The Year with no summer was well documented by the educated and wealthy, including Thomas Jefferson

In the United States, former president Thomas Jefferson left behind a record of meteorological events which was so detailed it remains in use by scholars and scientists studying the global disaster two centuries later. In modern times it is compared to scientific data acquired through means not understood in Jefferson’s day. For example, the studies of tree rings cut from trees which were alive during the catastrophe in Vermont indicate that for the period including 1816 there was little or no growth, which corresponds to the notes left by Jefferson in his Farm Book and other diaries, recording observations he made hundreds of miles to the south. Among the observations left by Jefferson are records of rainfalls, which while devastatingly heavy in some areas were scant in others, including Jefferson’s Virginia.

Jefferson wrote to Albert Gallatin towards the end of the summer of 1816 describing the shortage of rainfall which had been prevalent during the ending growing season, as well as the unseasonably cold temperatures. Jefferson, who used the records he had prepared every year since occupying his “Little Mountain” as a basis, informed Gallatin that an average normal rainfall for the month of August was 9 and 1/6 of an inch. Rainfall for August 1816 had been less than one inch; “we had only 8/10 of an inch, and still it continues”. He also noted the continuing cold weather conditions, including the frosts well to the north of Virginia, of which he had learned through his voluminous correspondence. Yet not Jefferson, nor any other student of science or the weather of the time, was able to postulate the global disaster had been due to a natural event, occurring many thousands of miles away.

3. In England, the army was called out to crush urban uprisings of the starving

England, which had been instrumental in the formation of the coalitions which crushed Napoleon, was particularly hard hit by the lack of a growing season. Unable to feed itself with the best of harvests, England found its own crops devastated by the adverse weather and its trading partners unable to provide food in sufficient quantities to make them affordable for most of its population. England had already endured years of shortages as the nation threw its might behind the wars with Napoleon, and the people by 1816 had had enough. As early as in the spring of 1816 food and grain riots were experienced in the west counties. In the town of Ely armed mobs locked up the local magistrates and fought the militia which mustered to rescue them.

By the following spring mobs in the urban centers of the midlands were common. Ten thousand armed and angry people rioted in Manchester that March. The summer of 1817 saw the British Army called to quell riots and other uprisings in England, Scotland, and Wales, while the transports to the newly established penal colonies were increased. Local landlords and magistrates often ignored the pleas of the authorities in London, establishing their own mini-fiefdoms through the promises of bread and grain. In England, as well as on the European continent, demands from the wealthier classes led to an increase in more authoritarian governments and the subsequent loss of civil liberties – such as they were at the time – in response to the international demand for food. On the other side, the suspicion that governments were hoarding food and grain at the expense of the poor led to a rise in radical thought, especially in France and the German principalities.

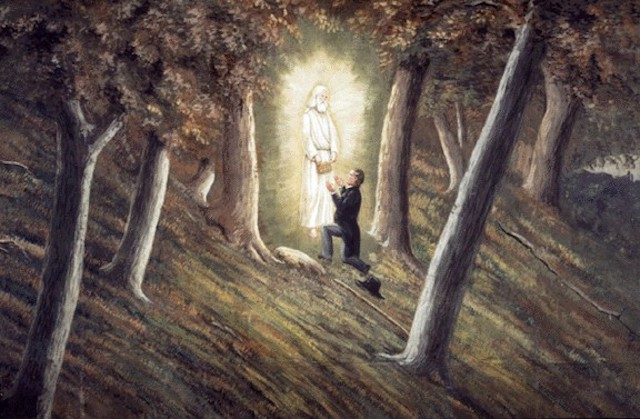

2. The Great Migration from New England to the west began in 1816

Most history books attribute the movement of the American agricultural population to the west following the War of 1812 to the end of the threat from the Indian tribes formerly supported by their British allies. The end of British influence was no doubt part of the mass migration, but it takes more than just the potential of new lands to uproot families from farms held by their ancestors for generations. The catastrophic crop failures which began in 1816 were a large part of the motivation for the movement to the west, as indicated by the massive depopulation of the New England states which began during the Year with no Summer. Particularly hard hit were Vermont and New Hampshire, as residents packed up and left for the west. For many of them, it was a journey away from divine punishment, a new exodus to a promised land, a view encouraged from pulpits.

A family from Vermont was one of them, which headed to the west into the lands which are now upstate New York, Indian Territory before the American victory during the War of 1812. The move coincided with a religious revival across America which became known as the Second Great Awakening, a return to the fundamentalism which had protected Americans from the ravages of an angry God, in the view of many. The family which settled for a time in New York were the Smiths, of Sharon, Vermont. While in their new home one of them, a son named Joseph, experienced the visions which eventually led to his discovery of the Book of Mormon. Without a rational explanation for the seemingly apocalyptic weather, divine explanations sufficed, not only among the Smith family, but with thousands of families fleeing what they were unable to understand, in search of an explanation and deliverance.

1. During the global cooling, the Arctic experienced warming and ice melt

As nearly all of the Northern Hemisphere in the climes occupied by humans felt decreased temperatures and abnormal rain patterns, the Arctic, including the ice cap, experienced a sharp increase in temperature which led to a melting of the ice at the top of the world. The receding ice cap allowed explorers, especially those from the United States and Great Britain, to travel deeper than ever before into the polar region, using waterways which until then had been unwelcoming sheets of ice. Since the days of Henry Hudson and the earliest English exploration of North America, the quest for the fabled Northwest Passage had occupied the minds of explorers and adventurers, and the opportunity presented by changing weather conditions was too good to pass up. 1818 was the first year in a new series of English led Polar Expeditions which continued for most of the 19th century.

Among them was an expedition led by Englishman John Ross which included a counter-clockwise navigation around Baffin Bay, which had the salutary effect of opening the waters for the exploitation of whaling ships. Though the Northwest Passage eluded him, as it did so many others over history, the boon to the whaling industry was immediate, and whalers from Great Britain and the United States were soon delivering the fine oil for illumination to ports around the world. By 1820 the effects of the Year with no Summer were relegated to history, a part of family lore in which elders described to children the weather events of the past as far more consequential than those of the current day. Unknown to them, the real effects continued for decades, and in some ways continue to this day.