It is unquestionably the most famous, the most slavishly observed royal family in the world. The 2018 wedding of Prince Harry and Meghan Markle garnered more than 29 million viewers in the United States of America alone, and the USA is not a nation you’d expect to be particularly friendly to the idea of royalty at all. And those were reported as being notably low ratings.

Now consider the extent to which British monarchs have left their direct stamp on the world as the nation grew into the empire on which the sun never set. How many people are familiar with Richard the Lionhearted and his role in the crusades but who couldn’t name another thing that happened a century before or after. Entire eras are named by historians in honor of Queen Elizabeth and Queen Victoria. Still, one of the lessons we’ve learned since we began TopTenz is that the more people have a passing familiarity with something, that usually means the more ways people misunderstand it.

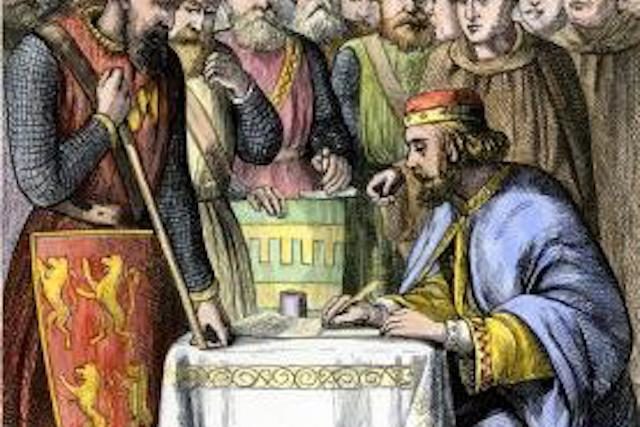

10. The 1215 Magna Carta was a Key Part of the American Revolution

For many American history students, when King John II signed this document, it was practically the birth of the American Revolution that would come five and a half centuries later. It was legal precedent that the powers of a monarch were to be held in check by outside powers, divine right or no divine right. The document included stipulations against the king being able to levy taxes as he saw fit, to regulate such seemingly mild matters as uniform measurements of a piece of cloth or corn in transactions. And that’s the thing: Many of those original clauses were subsequently removed.

The rewriting of the Magna Carta began almost immediately, in historical terms. As early as 1216, John’s successor Henry III was releasing a new version. Then it was changed again in 1217, and yet again in 1225. These were not slight changes, either. The 1225 revision, for example, cut the number of lines down from 63 to 36. Most significantly, the 1225 revision that was most momentous in being cited as precedent in 1628 included the right of the king to levy taxes at will. Considering that one of the main rallying cries of the American Revolution was “no taxation without representation,” then the Magna Carta was not actually useful as legal precedent for those who sought independence.

9. Richard the Lionheart was a High Point of the Monarchy

Many tellings of the story of Robin Hood present Richard I as the worthy king of England, and his younger brother John as the wretched usurper. It doesn’t hurt in some circles, particularly the papacy, that he was one of the primary figures of the third and most successful of the many European crusades in the Holy Land.

For one thing, Richard’s crusades were an immense strain on his nation’s finances. In 1190 he resorted to openly accepting bribes for political and legal offices. By 1192 he had been drawn into a stalemate against the Muslim forces and only won the right for unarmed Christians to enter Jerusalem. Then he lost a fortune in a far less defensible way when he was captured in a sea wreck, and his ransom cost literally two years worth of revenue for the entire nation, meaning even the wealth of the churches had to be seized. When Richard returned in 1194, he named John his heir, indicating he either approved of what John was doing in his absence or didn’t care, and then went to Normandy to resecure British control. He was killed there in 1199, having won neither of the wars he fought, spending barely any time in his home nation, and having bled it financially.

8. Henry V was a Glorious Leader

In 1415 a badly outnumbered, starving British army (the ratio has been reported as anywhere from two to one through five to one) used guile, longbows, and mud to soundly defeat a well-equipped French army. Consequently Prince Hal, as he was nicknamed before taking the crown, was put on a historical pedestal among monarchs and generals. Generations grew up hearing his stirring St. Crispin’s Day Speech, or rather the one that William Shakespeare wrote for him.

In truth, his glorious war in France was marred by two great atrocities. At Agincourt, when Henry’s army took a large number of prisoners, Henry ordered them put to death, which was a violation of the rules of war even at the time. In 1417 during the siege of Rouen, he outdid that atrocity when he allowed 12,000 French refugees to starve to death between his entrenchments and the city. It seems Shakespeare wrote something truer to the real man’s character than the St. Crispin’s Day Speech when he wrote in his play that the king who’d just claimed every man who fought with him would be of his “band of brothers” looked at a list of his dead soldiers, read the first four, and then said of the rest “none else of name.”

7. King George III was a Mad Tyrant

In North America, this monarch’s madness and the loss of the colonies are the only two things for which he’s remembered. There isn’t an entire film adaptation of a play devoted to his insanity with the unsubtle title The Madness of King George for nothing. It certainly helps paint the American Revolution as having additional justification if His Majesty across the Atlantic is unbalanced. Also, the fact that for the last decade of his reign he was so insane that Prince George IV was regent for Great Britain certainly adds to that.

The truth was that the king was, during the first 50 years of his reign, far more enlightened and tolerant of liberty than many monarchs before or after him. He had a keen scientific mind, being the first king in British history to receive an education in the sciences and enough interest in the subject to establish a royal observatory, which he used to accurately predict future transits of Venus. The Royal Library was freely offered to scholars during his rule. He made it his avowed policy to veto any legislation which would restrict the rights of preachers critical of the crown — “There shall be no persecution in my reign” were his strong words on the subject. He allowed the courts of Britain to make rulings independent of his judgement.

As far as America was concerned, for one thing, the unpopular taxes and policies were parliament’s decisions instead of his. During the American Revolution he kept detailed records of the troops and their supplies. When it was over, he worked to an amiable reconciliation between his empire and the new nation. While being the king meant losing the colonies was his responsibility, it was hardly the fault of his actions.

6. Queen Victoria was a Model of Repression

For awhile, there was a piece of trivia that circulated around about how, in Victorian England, there were skirts placed on tables for fear that the curves of a table leg might be too arousing. It was nonsense, but it fit an image of the era that had come to permeate the popular perception. With Queen Victoria as the figurehead of the period, it was inevitable that taciturn portraits of her from later in life would mean she was viewed as a stoic prude herself.

That would have been quite a surprise to many during much of her reign. When Victoria and Prince Albert were married in 1840, the press was agog about how glamourous and eager Victoria was. Victoria wrote to correct them only that she had not shed any tears. These feelings for Albert were not affected for public benefit: Victoria gushed in her diary about how she “NEVER, NEVER spent such an evening” and how his “excessive love and affection gave me feelings of heavenly love and happiness I never could have hoped to have felt before.” She also praised his appearance at length, from his “slight whiskers” to his “broad shoulders and fine waist.” These thoughts were not kept particularly private. She enthused to Prime Minister Melbourne about how Albert’s “kindness and affection… were beyond everything” over and over again. Not exactly X-rated material. But in an era where serious academic writings asserted that women did not experience orgasms, it definitely went against the grain.

5. King John was All Bad

With Richard I off in the Holy Land and Europe, triple-bankrupting England, regent (and eventual King) John took up the mantle of managing the homefront in a pretty bad spot, pretty much from the beginning. While Richard was winning battles, John had to be the bad guy who took wealth from churches to finance the war effort, winning him the animosity of historian monks such as Roger Wendover and Matthew Paris (although being excommunicated for trying to install a friendly archbishop for Canterbury certainly didn’t help). Add to that the fact his owns barons put him under threat of rebellion to sign the aforementioned Magna Carta, and everything is set up for him to seem like he must have been a travesty of a monarch, if not a person. But the man had his redeeming aspects.

As asserted by History Extra, John had a number of redeeming features and successes. Although landholdings were lost during his reign, he conducted a number of skillful sieges, such as Le Mans in 1200 and Rochester in 1215. He also lifted the Mirebeau. Indeed, he saved the defenders of the castle Chateau-Gaillard in 1203 through an amphibious assault that was praised by military historians. John was also able to maintain England’s power in Scotland and Ireland, which was particularly impressive while already being embroiled in a costly war across the channel.

In terms of administration, John was industrious to the point that he was credited with “modernizing” a government which had fallen significantly behind. As far as the Magna Carta was concerned, it should be noted that only a relatively few 39 baronies of the 197 in his kingdom were rebelling against him, while roughly as many were supporting him. Otherwise the barons certainly wouldn’t have bothered making him sign any documents when they could just depose him. However fraught with peril his reign was for England, in his own time he was hardly the mewling creep he has since been labelled.

4. King Alfred the Great Saved England from the Vikings

The general impression given is that, for centuries after the fall of the Roman Empire, Great Britain was essentially easy pickings for the Vikings. It wasn’t until the 9th Century that a particularly mighty king was able to unite the many states of the Isle and drive the raiders and their colonies out. Surely King Alfred would feel embarrassingly flattered by it, being a fierce advocate for education in addition to a highly effective general.

While it is true that by the time his reign ended in 899 Alfred had conquered London for the Anglo-Saxons and fought the Danes to a standstill and peace treaty, his descendants failed him in both military and humanitarian terms. In 1002, King Æthelred the Unready ordered the murder of all Danes on the island, which resulted in the St. Brice’s Day Massacre. This brought the full fury of the Danes under the command of King Sweyn Forkbeard, who subsequently conquered all of England. Thus Alfred could hardly have been said to have saved England from the Danes — he only delayed its full capitulation to them by roughly a century.

3. Queen Elizabeth I’s Virginity

Since her 1558-1603 reign was without a marriage or children, Queen Elizabeth I gained the label “the virgin queen.” Naturally this meant that many men, most notably the very incestuous King Philip II of Spain who’d already been married to her sister Mary, vied savagely for her hand. Recently, evidence has emerged that she was hardly chaste even after taking the throne.

In 2018, The Telegraph reported that Dr. Estelle Paranque had uncovered letters written by Bertrand Salignac de la Mothe Fénélon, a French noble who’d been stationed in England from 1568 to 1575 working as a diplomat. His letters, including one to Catherine de Medici, talked about how he’d received a number of invitations to Elizabeth I’s private chambers, how they’d reached a level of surprisingly casual and intimate conversation during their time together (e.g. her blaming him for forgetting her while he was away on business), and that she would at least once “drew (him) off in a corridor aside.” The tone of this correspondence was hardly bragging, with Fénélon writing admiringly of how the Queen looked “as a wonder” and admiring her for having the upper body strength to use a crossbow, which was unusual among noblewomen at the time. It’s not secretly recorded surveillance footage, but it’s the best evidence we’re likely to receive of such a liaison.

2. Henry VIII Exploded

After his death in 1547, it seemed like perfect propaganda for Catholic historians that the king had done so much to persecute for them to claim that his body had ignominiously exploded from all the gases stored in it as part of the rapid decomposition process, allowing dogs to have a taste of the royal remains. These days the little tale seems like a grimly amusing anecdote. Even to us, it feels like telling the truth is spoiling the fun a little.

Sadly, reports of the corpse of the Tudor king detonating aren’t so much exaggerated as they’re wrong. As recounted in Thea Tomaini’s 2017 book on the subject The Corpse as Text, another myth that emerged was that Mary Tudor secretly had her father’s body exhumed and burned, a fate Henry VIII visited on the corpse of Thomas of Canterbury. Mythmakers certainly thought that the fate of Henry VIII’s corpse was lively.

1. The Monarchy has No Power Currently

Moving into modern days, the monarchy of Britain seems so much less powerful that there is some controversy about whether the United Kingdom should continue to have a monarchy at all. It can be highly expensive to have such ceremonies as the annual inspection of the navy or those tightly-guarded royal weddings, not to mention that Her Majesty has an estimated net worth of $425 million and the Crown Estate owns £12.4 billion in land (though admittedly sites such as Fast Company report that it only comes out to 69 pence per taxpayer per year and more than makes up for its cost in tourism revenue).

Her Majesty currently has powers that would be fairly staggering for anyone who thinks she and the royal family are just figureheads. As head of state there’s the power to dissolve parliament and appoint a new prime minister, a power which extends to every state in the Commonwealth. She has veto power for all bills being signed into law. She appoints bishops and archbishops in the Anglican Church (if they pass muster with the prime minister). On a lighter note, she has carte blanche ability to issue money to senior citizens on Easter. If someone considers that a figurehead, we’d hate to see what they consider a micromanaging tyrant.

Dustin Koski wishes good health to the royal family. He is also the author of the dark fantasy novel Not Meant to Know.