Italian surgeon Sergio Canavero made headlines recently for claiming he has the ability, right now, to transplant a live human head onto a corpse and successfully reanimate both. Of course, experts dismiss him as a quack (giving a TED talk doesn’t necessarily make you reliable), but few seriously doubt that what he says is theoretically possible. Whether or not Canavero gets there first, we’ll almost certainly be able to do it one day—and when that day comes, we’ll definitely go ahead and do it.

Because regardless of the controversy and ethical concerns that inevitably surround such a procedure, human head transplantation would only be the latest development in a long history of grisly, Frankensteinian, but nevertheless life-saving, science.

From the golden age of alchemy to some of the more bizarre mix-and-match transplants of late, here are some of the highlights.

10. Abu Musa Jabir ibn Hayyan (721-815)

Abu Musa Jabir ibn Hayyan (or Geber, as he became known in Europe) is one of history’s most notable alchemists, having written dozens of treatises on the subject—including the seminal Kitab al-Kymya, from which we derived the word ’alchemy’.

He also laid the foundations for the periodic table and introduced basic equipment (such as the alembic and retort), processes (such as crystallization and distillation), and terminology (such as ’alkali’) that are still used by chemists today. Some historians actually credit Jabir ibn Hayyan with the founding of modern chemistry, having transformed the mystical, largely theoretical focus of alchemy with his own more practical, experiments-based approach.

Still, many associate his name with the so-called takwin, a little homunculus-type creature that he claimed could be made in a lab. This was a common belief in the Middle Ages, that artificial life might be possible, but Jabir ibn Hayyan actually gave instructions. To give life to a takwin, he wrote, one must combine blood, semen, and various body parts in a glass vessel shaped like the creature to be made.

It’s unclear (but, let’s face it, doubtful) that he ever actually made one. However, given his strong emphasis upon empiricism, it’s also hard to believe that he would have just made it up. Unless of course, as he implied himself in the Book of Stones, the purpose was “to baffle and lead into error” mad scientists more sinful than he.

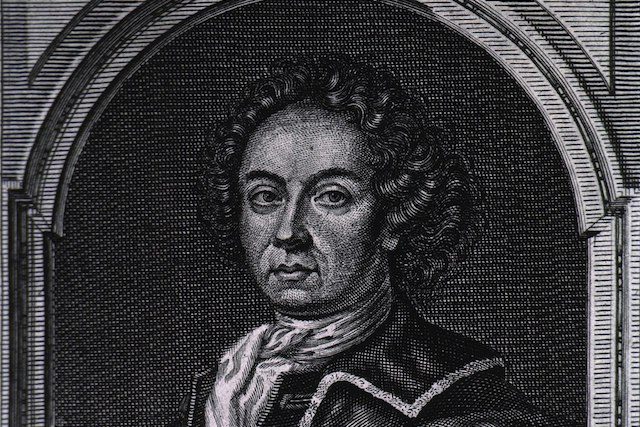

9. Johann Dippel (1673-1734)

Born at Frankenstein Castle, south of Darmstadt, southern Germany, Johann Dippel’s childhood education was deeply religious, led for the most part by his own pastor father. By the age of 9, however, he began to express his doubts about the Church, and by the age of 14 he was accused of keeping the company of familiar spirits or demonic helpers.

Although he went on to study theology, he was continually questioning the Church and changing his position, ultimately turning his attention to science and alchemy instead. He dabbled in transmuting base metals into gold, for instance, and distilling animal parts for medicinal oils—the most notable of which was the black, foul-smelling Dippel’s Animal Oil made from leather, blood, and ivory and marketed as an elixir of life. He also claimed the oil could be used to exorcise demons, which he mentioned in his work alongside transferring souls between corpses using a funnel.

Dippel’s Animal Oil enjoyed only brief and modest popularity as a diaphoretic (or sweat-inducer, perhaps understandably) and anti-spasmodic. Despite Dippel’s claims that it was capable of curing pretty much anything, including death, it fell out of favour before long. The fact that Dippel himself died early, having predicted he’d live to 135, can’t have helped.

The fetid black oil did make a comeback during the Second World War, though. It was used to coat the insides of enemies’ wells and make the water undrinkable.

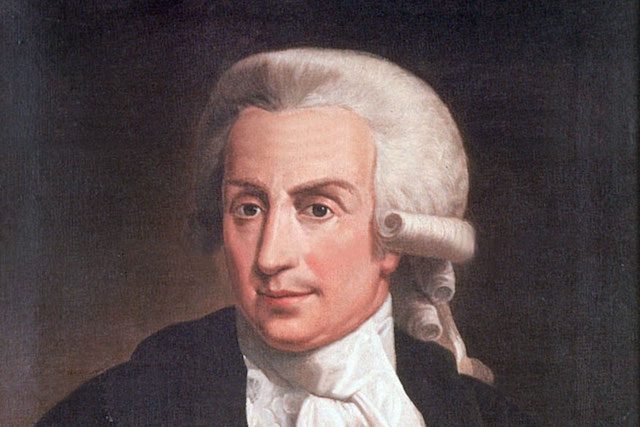

8. Luigi Galvani (1737-1798)

Many real-life Frankensteins, as well as Mary Shelley herself, were inspired (you might even say galvanized) by the work of Luigi Galvani, the electrophysiologist who came up with the concept of galvanism and the use of electricity to stimulate life.

Back when Galvani was conducting his experiments in the second half of the 18th century, electricity was still a fairly new and exciting development. Most scientists barely understood it. But Galvani saw in it great potential for the advancement of medical science.

In 1786, having made a dead frog twitch merely by touching its nerves with scissors during a lightning storm, he theorized that animals produce electricity of their own. He tested and confirmed his suspicions on countless other frogs and suggested this animal electricity was secreted as a kind of electrified substance from the brain. Although his work was contentious at the time, it did lead one of his most vocal critics, Alessandro Volta, to invent the voltaic pile—an early electrical battery.

Unfortunately, when Galvani refused to swear allegiance to Napoleon, he lost his professorship and salary and died a little while later, right on the cusp of the electrical revolution that he helped bring about.

7. Giovanni Aldini (1762-1834)

Galvani’s nephew, Giovanni Aldini, was fascinated by his uncle’s experiments and eager to carry the torch. But not by experimenting on frogs. Aldini had his sights set on larger animals like cows and pigs, whose cold, dead bodies, tongues, and eyeballs he caused to shake and move about by applying electrical current.

Later, perhaps inevitably, he turned his attention to humans, using a massive voltaic pile with hundreds of metal discs to apply electricity to headless corpses. And as Frankensteinian as all this sounds, none of it took place in a ruined Gothic castle in the middle of a violent thunderstorm; in fact, Aldini performed most of his gruesome experiments in broad daylight before a horrified crowd on the Piazza Maggiore in Bologna—right outside the Palace of Justice that donated all of his corpses.

Although he was able to produce some of the same contractions and twitches that he’d already seen in animals, he was disappointed to find that hearts didn’t seem to respond. There was also a mere three hour window after death in which any effects could be observed. Deciding he needed a corpse that hadn’t lost so much blood, Aldini travelled to London in search of a hanged, not decapitated, criminal.

It didn’t take long to find his test subject—the corpse of a man named George Foster—to which he immediately set about applying electricity. According to Aldini’s report, “the jaw began to quiver, the adjoining muscles were horribly contorted, and the left eye actually opened.” When he stimulated the rectum with his rods, the whole body convulsed so much “as to give the appearance of reanimation.” Eventually, however, the battery died and Foster along with it (for the second time that day).

But the interest and awe that Aldini evoked within both the scientific community and the public at large almost certainly inspired Mary Shelley. And Aldini, who is said to have shared some of Victor Frankenstein’s mannerisms, was actually alive for the book’s publication.

6. Andrew Ure (1778-1857)

A professor of Chemistry and Natural Philosophy at Glasgow, Scotland (following a stint as an army surgeon), Andrew Ure was eager to further the work of his groundbreaking Italian peers. And he jumped at the chance to experiment on the corpse of one Matthew Clydesdale, the first person to be publicly hanged in the city for years.

Right after the execution, the man’s body was sped by horse and cart to the university’s anatomy theater—where the good doctor was patiently waiting with his battery already charged. He made no secret of his intentions. He wanted to resurrect the dead. And according to an (alleged) eyewitness report, the experiment was such a success that Ure was forced to slit Clydesdale’s throat with a scalpel to make sure he died for good. That probably didn’t happen, of course, but the established facts are just as grisly.

First, the corpse was sliced open to reveal the sites for stimulation. Then Ure attached electrical rods to the heel and spinal cord, causing Clydesdale’s bent leg to straighten and kick out, almost toppling one of Ure’s assistants. They also applied electricity to the left phrenic nerve and diaphragm and were delighted to see the corpse start “breathing.” When they applied electricity to the supraorbital nerve and heel, however, the “most horrible grimaces were exhibited …. Rage, horror, despair, anguish and ghastly smiles united their hideous expression in the murderer’s face, surpassing far the wildest representations of Fuseli…” In fact, this horrified spectators so much that many left in disgust, throwing up or even fainting on their way out.

Ure’s experiments might seem frivolous today, but he effectively invented the defibrillators still used around the world to jolt cardiac arrest patients back to life. On the basis of his experiments, he rightly claimed that, instead of direct stimulation, two moistened brass knobs connected to a battery and placed against the skin over the phrenic nerve and diaphragm could restore life to the clinically dead.

5. Andrew Crosse (1784-1855)

Tinkering around on his inherited estate in the countryside, Andrew Crosse was, unlike most on this list, an amateur scientist as opposed to a respected professor. However, his eccentrically obsessive fascination with electricity more than earns him a place on this list. Indeed, Mary Shelley once attended one of his lectures and was undoubtedly impressed by his work.

To his country bumpkin neighbors, meanwhile, Crosse became known as the “Wizard of the Quantocks,” or the “Thunder and Lightning Man,” for wiring up his grounds in such a way that during thunderstorms his music room would come alive with fiery sparks and loud, crashing noises. According to one local, it was actually dangerous to go anywhere near his house at night because of the “devils, all surrounded by lightning, dancing on the wires.”

Crosse himself saw electricity as a kind of mystical force, a divine creative power that could be harnessed by man. He is best known, perhaps, for apparently creating spontaneous organic life in the lab. It wasn’t deliberate; he’d actually been attempting to generate crystals by passing electrical current through a piece of volcanic stone submerged in acid, but was astounded to see little mites emerging and wriggling their legs after 26 days as white bumps.

Although he was just as mystified by this as anyone else, including other scientists who managed to replicate his results, Crosse was denounced as a blasphemer and inundated with death threats. Naturally, the publication of Frankenstein only made matters worse. And, as if knocking God off his pedestal wasn’t bad enough, local farmers complained the mites (which Crosse named Acarus crossii after himself) were running amok and blighting their crops.

In all likelihood, as Crosse himself suggested, his apparatus was merely contaminated with eggs.

4. Sergei Bryukhonenko (1890-1960)

Sergei Bryukhonenko stepped things up a notch on the Frankenstein front by demonstrating that organs could be kept alive and actually functioning even after their removal from the body. He was able to do this by circulating oxygenated blood, as well as air when necessary, to keep lungs “breathing,” hearts beating, and even brains semi-cognizant. When he hooked a severed dog’s head up to his ’autojektor’ pump, for instance, it reacted to external stimuli just as though it were living. It blinked when its eyes were prodded, licked its lips when citric acid was applied, and pricked its ears to loud noises nearby.

Organs hooked up in this way only stopped working when the blood in the autojektor coagulated—after 100 minutes or so—due to it not being hermetically sealed.

When rumors of this mad commie scientist “resurrecting the dead” reached America, Bryukhonenko became a sensation. The implications were huge. As George Bernard Shaw remarked when he heard the news, he’d happily have his head removed and kept artificially alive if it meant he could go on working without getting ill.

Obviously, it wasn’t that simple. While Bryukhonenko did experiment on humans next, he wasn’t all that pleased with the results. Having sourced a fresh, relatively unscathed corpse from a man who’d hanged himself three hours earlier, Bryukhonenko had hooked up a vein and an artery to the autojektor and waited for the blood to re-oxygenate. Within hours he and his assistants had detected a heartbeat. But then there came a terrifying gargling sound, or death rattle, from the throat and the eyes snapped open, staring at the surgeons and scaring them all so much that they stopped the autojektor and let the corpse rest in peace.

3. Robert E. Cornish (1903-1963)

American mad scientist Robert Cornish was so confident in his ability to bring back the dead that he actually suffocated dogs to resuscitate them. This usually involved rocking them back and forth on a teeter board to get the blood flowing. And unfortunately it rarely worked; even when it did, the dogs (all named Lazarus) wound up with brain damage. Eventually, in response to bad press, Cornish was fired from his position at UCLA.

But he continued his experiments at home. He even played himself in a movie about his work and, in 1947, petitioned the State of California for permission to resurrect a death row inmate. The condemned man—who’d been sentenced to death in a gas chamber for kidnapping and murdering a 14-year-old girl—had actually volunteered his own body to Cornish, but their request was ultimately denied. According to the State, it would be far too dangerous to allow Cornish access to the body before fully venting the gas chamber and, since this could take up to an hour, the body would be useless to the doctor.

According to lawyers, however, the State was likely more concerned that Cornish might actually succeed. After all, if the murderer was brought back to life having served out his death sentence in full, they would have no choice but to let him walk free.

2. Vladimir Demikhov (1916-1998)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uvZThr3POlQ

So far on this list, we’ve been missing a vital Frankensteinian trope: the mixing and matching of body parts. Enter Vladimir Demikhov, who, in 1959, was featured in LIFE magazine for creating a two-headed dog.

To do so, he and his team got hold of two healthy (but apparently unloved) specimens—a big dog and a small dog—from dogcatchers. They cut the larger dog’s neck to expose the jugular, aorta, and part of the spinal column. Then they prepared the smaller dog by tying off the main blood vessels and severing the spinal column while keeping both the head and forepaws intact and connected to the heart and lungs. Finally, they connected the blood vessels of the smaller, now partial dog to the corresponding blood vessels of the larger dog and voila. Remarkably, the experiment was a success. Both dogs survived the procedure and were able to see and move independently.

The fact that they died just four days later should not detract in any way from Demikhov’s horrible achievement. His work contributed a great deal to the development of life-saving heart surgery and organ transplantation. Indeed, Christiaan Neethling Barnard, the first surgeon to successfully transplant a heart from one human to another, credited Demikhov with having pioneered the field.

1. Robert J. White (1926-2010)

Demikhov also inspired the neurosurgeon Robert White to carry out head transplants on live monkeys (although, as an observant Catholic and believer in the brain as the seat of the soul, White preferred to call this procedure a ’full body transplant’).

After attaching the entire head of one monkey to the decapitated body of another, with all of the nerves intact, White found the animal could see, hear, taste, and smell. He hoped this might one day be translatable to humans, potentially helping patients with multiple organ failure or terminal illnesses to turn their ailing bodies in for fresh and healthy (albeit until recently dead) replacements.

But even one of White’s own colleagues believed he was being naive. There were, for example, serious ethical concerns; although the monkey survived the procedure, it looked confused and panicked, not to mention in pain, when it woke up. White had little time for animal welfare when it came to the advancement of science and vehemently opposed organizations like PETA standing in his way, but his colleague undeniably had a point when it came to humans. After all, regardless of what Catholics might say about the brain as the seat of the soul, human identity is inextricably linked up to our bodies. Can we really just stick a head from one body onto another and pretend it’s essentially the same person?

Nevertheless, White defended his work by pointing out that every new development in the Frankensteinian history of organ transplantation has been met with serious controversy. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein itself is a fine example of just this kind of soul-searching at the nexus of science and morality.

And if Sergio Canavero is to be believed, if we really are on the verge of human head transplantation, then Shelley’s classic tale is about to become more relevant than ever.