Let’s get this out of the way before we really get started: of course no one needs to be told that a coalition of states that was formed largely to keep four million Black people in bondage won’t be good for that group.

What’s been forgotten, even by those that are working to whitewash more than a century of “Lost Cause” propaganda by groups such as the Daughters of the Confederacy, was that huge sections of the white population had very good reasons to not want to live in the South either. Many of these were the case both during the war and during the lead up to it. It could be argued that some of them were only a consequence of the pressures of war at the time and would have gone away if the Confederacy had miraculously won, but considering how many of these problems continue to this day in one form or another, it’s quite possible that a Confederate government would have made them only worse.

10. Slavery’s Threat to Working Free Men

When it comes to labor costs, there’s just no competing with free. For working class men in the Southern states, their wages were massively undercut precisely because of this. While slaves were mostly used for agriculture, even free laborers in industrial jobs such as construction had their labor bargaining power taken away by the fact state governments required slave owners to donate the efforts of their slaves for public works, which ultimately resulted in hundreds of thousands of slaves filling those positions permanently. So it was that by 1860, free laborers in the South averaged $103 a year while laborers in the North averaged $141 in the same time period.

This had a secondary benefit for the slave-owning class. As a result of a lack of livable wages in most industries, many white laborers had to turn to the slave trade themselves. Overseers and slave-catchers who relied on keeping Black slaves in line developed an additional racial resentment, increasing public support for slavery.

9. Food Shortages

It’s understandable that, late in the war, supplying the people with food would be difficult. Not only was the blockade by the Union navy cutting down the flow of supplies, but the Union armies were deliberately disrupting rail lines and other transportation methods to disrupt the war effort. In fact as early as June 20, 1861, only a few months into the war the New York Times was reporting how food prices were so much higher in Southern cities than those in the North, such as the fact a bushel of corn cost $0.56 in New York City and $0.70 in Memphis, or that a barrel of pork cost $17.50 in Philadelphia and $26 in New Orleans. This disparity only got worse as the war went on, especially when the Confederates started mass printing money and hyperinflation set in to the point there were bread riots, such as in the Confederate capitol city Richmond, Virginia.

Initially the Southerners thought that their agricultural economy would allow their secession to starve the North. In reality, reliance on slave labor had given Southern farm owners less motivation to mechanize, so two-thirds of all farm machinery was used in Union farms, and a much more robust infrastructure allowed for faster distribution before food spoiled. As a result, the Union enjoyed such advantages as 80% of wheat production and nearly as much oat production. Thus did slavery stifle innovation when the Confederacy needed it most.

8. Private Property Confiscation

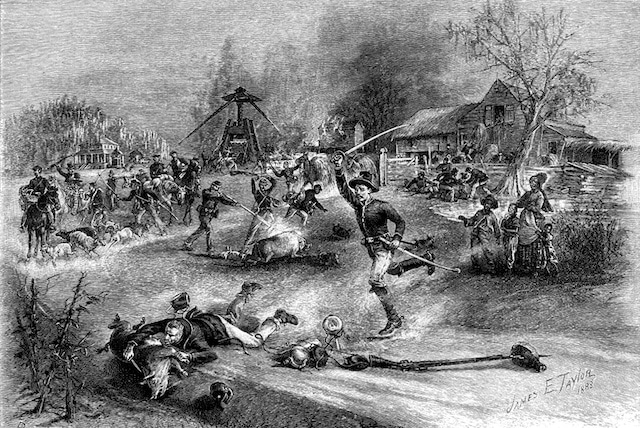

In August 1861 the Union congress passed the First Confiscation Act, which was largely a pretext for freeing slaves by seizing them as property. In retaliation, the Confederate congress passed the Act of Sequestration in the same month, which declared anyone disloyal to the Confederacy could have their property seized by the government. Although this was intended to aid the seizure of Union property, it quickly spiraled out of control because government agents had to rely on local, potentially grievance-driven testimony for who was disloyal.

The region that got it the worst from this policy was Eastern Tennessee. This area was strongly pro-Union (it voted against secession more than 2 to 1), so clashes with the Confederate government were all but inevitable. Many homes were confiscated in this already impoverished region, and the people were so infuriated that on November 8, 1861 teams of aggrieved Southerners set fire to four vital railroad bridges. Eastern Tennessee was hardly alone, though. By the end of the war, millions of dollars of property in North Carolina were also confiscated, and many of the government employees seizing the property didn’t even keep track of the seizure, leading to large amounts of “lost” property.

7. Suspension of Habeas Corpus

One of the most common criticisms of Abraham Lincoln‘s presidency was when he suspended habeas corpus (aka, right to a trial) in April 1861. Much less well known is that the Confederacy did the exact same thing from 1862 to 1863, only they went a step further than Lincoln when they renewed it from 1863 to 1864.

Some have argued that this was more a formality, for the Confederate military arrested thousands of civilians and held them without trial whether Habeas Corpus was officially suspended or not. Indeed, the literal day the war started when Fort Sumter was fired upon, a Florida reporter was arrested for being critical of the action and held indefinitely without trial. As we’ll see in other entries, these were circumstances under which a suspect would desperately want a trial.

6. Public Education Failure

Since much of the South was more rural than the North, and thus children from an early age would be needed for farm work, only roughly 50% of the population went to public schools (compared to about 90% in the North). Massive income inequality as described in the first entry exacerbated the problem, as the elites would send their children to private institutions, further cash-starving schools in lightly populated areas.

That’s not to say that there weren’t efforts to work against that. Sarah Hyde’s Schooling in the Antebellum South describes how there were concerted and temporarily successful grassroots efforts to expand public schooling in Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama during the decades leading up to the Civil War. Unfortunately the efforts were thwarted by economic disasters such as the Panic of 1837. It was an inherent flaw in a society so badly afflicted with income inequality.

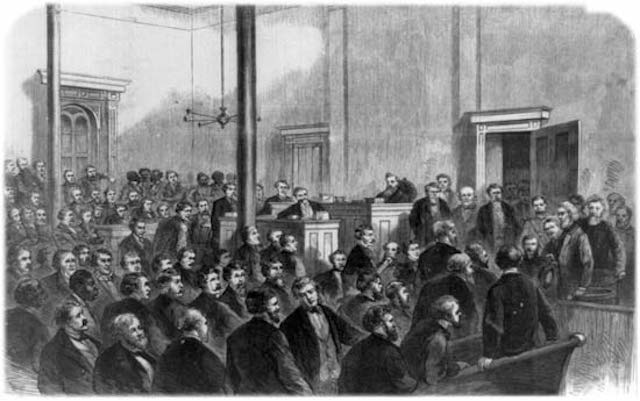

5. Executed for Suspected Disloyalty

You wouldn’t know it from common portrayals of the war, but 100,000 white soldiers from Confederate states fought for the Union, largely as scouts and anti-guerrilla troops in occupied areas. North Carolina alone provided 10,000. Under circumstances where loyalties were much more divided than we’ve long been led to believe, paranoia and the descents into extreme cruelty it can bring exploded across many areas in Southern states.

For example, on October 1, 1862, seven white men in Red River, Texas were hanged for suspected sympathies to the Union. They were actually examples of the Confederates in relatively restrained mode, for at least they were granted a show trial. Soon after another 14 were executed without even that. By October 14, 40 suspected Unionists had been hanged and two had been shot dead. The year before in St. Francis and Pope Counties in Arkansas Unionists were killed or driven from their farms. Hardly surprising that in many areas in western Confederate states guerrilla warfare broke out that lashed out in both directions.

4. Alcohol Prohibition

This may seem relatively petty compared to property seizures and executions, but considering that in the 19th Century Americans drank an average of three times more than they do now, disrupting the production of alcohol had tangible consequences for many Southerners, particularly those vulnerable to delirium tremens. And yet Confederate states still passed such draconian laws as when Tennessee banned selling liquor, the most popular drink in America at the time, within four miles of any “national or confederate soldiers home.”

Even that was mild compared to what happened to whiskey and brandy, which were made illegal to distill throughout the entire Confederacy. The official reason was that the corn and other products used were needed to combat food shortages, but in private it was more because the copper used in distillation was needed for artillery.

As with the famous Prohibition of the 1920s and ’30s, these alcohol restrictions were massively counterproductive. For example on March 1, 1862, General John Winder banned liquor sales in general and closed saloons. In response the provost guards continued getting seemingly as much alcohol as before by forging prescriptions to acquire liquor from apothecaries. A large number of pharmacists were arrested as a result of providing contraband liquor.

3. Travel Restrictions

On April 12, 1862, the Confederacy began a travel pass system. It required anyone moving between states to have a brown booklet with them. Both sides in the war were rife with spies, and from early on the Southern armies had severe problems with desertions. Although they were primarily used for train passengers, as foot and privately-owned vehicular travel were not similarly restricted, a large number of able-bodied men were detained for not having them handy.

Of all the restrictions placed on freedoms in the Confederacy, this was one that went over really badly. The main bone of contention was that the requirement was too reminiscent of the papers that slaves had to have on them when they traveled with their masters. It certainly didn’t help that the Union was amazingly lax about travel passes, not even requiring people coming from the South until 1863.

2. Anti-German Sentiment

The abolitionist bounty hunter Dr. King Schultz from the 2012 film Django Unchained is more realistic than he might have seemed. German immigrants to America in the 19th Century tended to be the most ardent abolitionists in America, comprising the largest single ethnic group that fought for the Union during the Civil War while only about 20% as many fought for the Confederacy. For many German immigrants in the South, the consequences of this vocal opposition were deadly.

In August 1862, 68 German immigrants from the Hill Country area in Texas struck out for the Mexican border as part of a roundabout way to get sanctuary in the Union-controlled city of New Orleans. They were intercepted by Confederates under Captain James Duff at the Nueces River. In what was subsequently described as a battle or a massacre, 36 immigrants and 12 Confederates were killed, nine of the immigrants having been killed after they surrendered. The subsequent memorial that was built to mourn the fallen is the only such monument in the Southern states written in German.

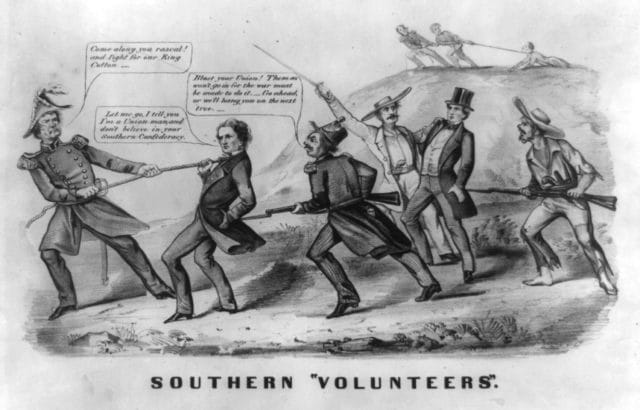

1. Conscription

In April 1862, the Confederacy passed the first conscription act of the Civil War, which left all able-bodied men between the ages of 18 and 35 liable for three years service unless they held a job essential to the war effort. From the beginning this was not a law that was taken lightly. For instance the same Captain James Duff that oversaw the deaths of all those German immigrants at Nueces began enforcing the conscription in Hill Country. His methods would include burning down homes and executing 20 people opposed to the draft. Indeed, the draconian enforcement of the draft was a significant factor in those immigrants’ attempt to leave Texas in the first place.

There were two provisions that particularly bred resentment against the conscription act. First there was the fact that a substitute could be hired to serve as a replacement for $300. Second was that people who owned 20 slaves were exempt from the draft (though this was changed… by lowering it down to 15 slaves). This led to a popular saying at the time that it was a “rich man’s war and a poor man’s fight.” It cost even more people their lives during such protests as Newton Knight’s infamous anti-Confederacy uprising in Jones County, Mississippi. As vitally important as race was as a motivator for the Civil War, the significance of class shouldn’t be overlooked.

Dustin Koski was a coauthor with Jonathan Wojcik for the supernatural horror comedy Return of the Living.