Combat journalism is nearly as old as war itself. The famous ancient Greek historian, Herodotus, set a high standard with his detailed accounts of the Greco-Persian wars, underscoring the importance of recording conflicts that would shape history. However, it often comes at a steep price.

Truthful reporting uncovers muddled propaganda, informing society and conveying urgently needed transparency. But fact-finding can be deadly — especially in political hotspots and battlefields around the world. The following list shines a spotlight on the brave men and women who went to war and never came back.

10. Marie Colvin

As one of the most prolific war correspondents in recent decades, Marie Colvin routinely risked her life to report from the front line. The hard-drinking, chain-smoking American journalist was known for both her fearlessness and abrasive demeanor. She established a well-earned reputation by venturing into danger zones often overlooked and where others feared to go.

Her travels took her from Afghanistan to Zimbabwe and all hostile regions in between. While covering the civil war in Sri Lanka in 2001, she lost an eye in a grenade attack and wore a black eye patch that became her defiant trademark. Colvin’s relentless courage and swagger became the stuff of legend during an incident in East Timor, where she helped save over 1500 women and children under attack by Indonesian-backed forces.

Unmasking the subterfuge that often surrounds war became another defining trait throughout her career. And it would ultimately cost her life. On assignment for the Sunday Times, she revealed atrocities against civilians in Syria by the Assad-led government, such as the use of chemical weapons. She gave her last broadcast on February 21, 2012, from the besieged city of Homs, and was killed the following day from a rocket attack by Syrian artillery.

Colvin’s devotion to exposing human rights violations continues to be her enduring legacy. Her life has been the subject of several recent books and documentaries, including the 2018 film, A Private War.

9. Bill Stewart

ABC news correspondent Bill Stewart got out of his press van on June 20, 1979, near a roadblock in Managua, Nicaragua. He had been covering the escalating civil war between Sandinista rebels and government troops under President Anastasio Somoza. An armed National Guardsman ordered Stewart and his interpreter, Juan Espinosa, to lie on the ground. Moments later, the soldier aimed his rifle and shot both men dead at close range.

Although only 37 at the time of his death, Stewart was already a veteran newsman, having previously covered the fighting in Lebanon and the revolution in Iran. He had been in Nicaragua for 10 days reporting from the inner city of the capital, an area of some of the most intense battles between the two sides.

Stewart’s murder, recorded by fellow ABC reporters and broadcast in the U.S., spurred an international outcry that eventually led to the ouster of Somoza’s brutal regime. The incident occurred a day after the government-owned media attacked foreign reporters covering the war, accusing them of taking part in an “international communist conspiracy.” In Washington, President Jimmy Carter responded, stating ”The murder of … Bill Stewart in Nicaragua was an act of barbarism that all civilized people condemn.”

8. Tim Hetherington

Like many on this list, Tim Hetherington’s immense body of work saw him cast in multiple roles: photojournalist, filmmaker, artist, author, and human rights advocate. The Briton is probably best known for Restrepo, an award-winning documentary which he co-directed with Sebastian Junger about life inside an American outpost in Afghanistan’s Korengal Valley, an area considered one of the most dangerous locations in the lingering war against the Taliban.

Hetherington’s interests extended far beyond his high profile war assignments for magazines such as Vanity Fair and field reports for ABC News. Although he held degrees from Oxford and Cardiff University, he chose to spend eight years living and working in West Africa, gaining invaluable insight of the hardships inside the shattered region during the second Liberian civil war. His passion for humanitarian causes later qualified him to work with the United Nations Security Council as an investigator for the Liberia Sanctions Committee.

During the Arab Spring of 2011, he found himself in yet another dangerously hostile predicament. On April 19 he tweeted out: “In besieged Libyan city of Misrata. Indiscriminate shelling by Qaddafi forces. No sign of NATO.” The next day he was hit with either shrapnel from a mortar shell or an RPG (Rocket-propelled grenade). Like Robert Capa before him, he was 40 years old at the time of his death.

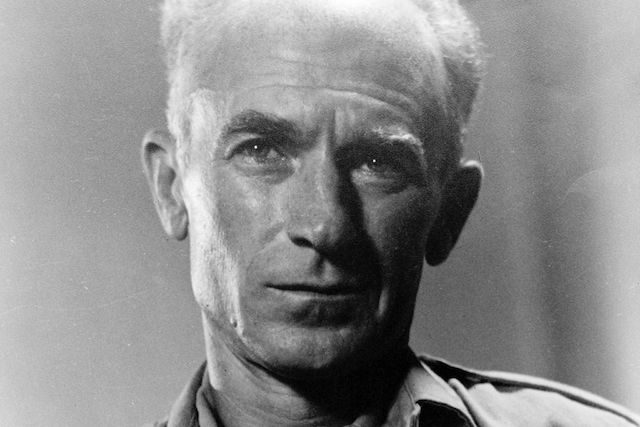

7. Ernie Pyle

A recent tribute on the U.S. National Archives website described Ernie Pyle as someone who “was able to tell the stories of enlisted men because he embedded himself in their day-to-day lives; he didn’t just observe their work, he lived, traveled, ate, and shared foxholes with them.” An apt summary of an ordinary newsman with an extraordinary talent for putting a human face on the dehumanizing toll of war.

Originally from Indiana, Pyle got him his start in journalism writing for his school newspaper at the University of Indiana. He would develop his Mark Twain-esque, homespun style as a roving reporter for the Scripps-Howard newspaper chain. Usually accompanied by his wife “Jerry,” Pyle wrote primarily human interest stories six days a week for his popular “Hoosier Vagabond” syndicated column. The couple eventually settled in Albuquerque, New Mexico, where his house would later become a public library.

At the start of WWII, Pyle crossed the Atlantic to cover the Battle of Britain, transitioning into a masterful war correspondent. America’s subsequent military involvement saw him reporting from the frontlines in North Africa, Sicily, Italy, and France with his dispatches appearing in over 400 daily newspapers. Pyle won the Pulitzer Prize in 1944 for his first-person accounts about infantry soldiers that he championed as “the guys that wars can’t be won without.”

After seeing his share of danger in Europe, Pyle reluctantly took an assignment in the Pacific Theater. Japanese machine-gun fire ended his life shortly after his arrival during the invasion of Okinawa. Shortly afterward, a movie based on his wartime stories was released called The Story of G.I. Joe. Starring Burgess Meredith as Pyle, the film earned four Academy Award nominations and launched the career of a young actor named Robert Mitchum.

6. John Hoagland

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cCMJLObzJbc

By the spring of 1984, American photojournalist John Hoagland had managed to carve out a seemingly impossible idyllic world for himself in the sleepy coastal town of La Libertad, El Salvador. The 36-year-old San Diego, California native had recently married a local woman, who also shared his passion for surfing and nature despite the ongoing civil war spiraling out of control all around them. But true to his character, Hoagland chose to stay put, using his camera to tell stories about life and death in the small Central American country.

Like many young people in the politically turbulent 1960s, Hoagland became involved in movements regarding social justice and civil rights. He joined his fellow students at the University of California, San Diego in several protest marches and briefly served as a bodyguard for civil rights leader Angela Davis. He later traveled to Nicaragua where he found his calling as a combat photographer, quickly establishing a reputation for both his tenacity and calm under fire. In addition to covering the Sandinista revolution, he photographed the conflict in Beirut, freelancing for news agencies such as the Associated Press and United Press International.

Back in El Salvador, the situation went from bad to worse. Government death squads slaughtered innocent civilians at will. Priests were murdered. Nuns were raped. And the U.S. financed, Salvadoran Army carried out a scorched earth policy against leftist guerrillas — and anyone else who defied its authoritarian rule. Hoagland soon learned he was one of 35 journalists whose names appeared on a paramilitary “death list.”

While on assignment for Newsweek, he traveled with a CBS News crew towards the town of Suchitoto just north of the capitol in San Salvador. On March 16, 1984, a firefight broke out between the Army and rebel forces along a rural dirt road. Hoagland, as usual, was 50 yards ahead of the other reporters when a large caliber round from an M-60 machine gun penetrated his back. His camera was still clicking away as he fell to the ground and eventually bled out.

5. Dan Eldon

Dan Eldon led an exceptionally full life. He globe-trotted extensively around the world, visiting 46 countries on four continents while creating art and establishing charities along the way. He also managed to attend college in California and work as a graphic designer in New York before emerging as an acclaimed photojournalist in Africa. But above all else, Eldon was a humanitarian — and helped improve hundreds of thousands of lives in the most poverty-stricken countries. And he accomplished all this by the time he was 22.

Born in London to a British father and American mother in 1970, Eldon and his family moved to Kenya when he was seven. He chronicled his adventures throughout his life in a series of journals comprised of assorted drawings, photographs, and writings. A collection of these diaries would later become an international best-selling book: “The Journals of Dan Eldon: The Journey is the Destination.”

In 1989, a sight-seeing trip with friends through southeast Africa provided an unexpected discovery that affected him profoundly. A recent civil war in Mozambique had caused thousands to flee across the border and crowd inside a large refugee camp in Malawi. Spurred by what he saw, Eldon created Student Aid Charity, raising much-needed funding for people decimated by conflict.

Another civil war, this time in Somalia, landed Eldon back in Africa in the summer of 1992. The fateful event transformed him into an internationally renowned correspondent as well as impact an entire nation. In the town of Baidoa, Eldon witnessed an area ravished by famine and destruction. His haunting photographs of dead babies and skeletal survivors made front page news and were on the covers of magazines worldwide — but more importantly, served notice of a staggering humanitarian crisis.

The awareness helped trigger an international relief mission, Operation Restore Hope, but attacks by warring factions also led to the arrival of heavily armed “peacekeeping forces.” Meanwhile, Eldon (now working for Reuters), continued immersing himself within the community and became such a popular figure among the locals that they nicknamed him “Mayor of Mogadishu.”

On July 12, 1993, U.N. troops mistakenly bombed a Somali villa believed to be the headquarters of a powerful warlord named Gen. Mohammed Farah Aidid. Instead, several hundred people were killed or wounded, including several revered elders and imams. Eldon and three other journalists were summoned to document the carnage and rushed to the scene. In the confusion and mayhem, an angry mob turned on the reporters, killing Eldon and the others by stoning them to death.

4. James R. O’Neil

The American Civil War is considered the first major conflict to be extensively photographed. The expensive, bulky equipment, however, proved difficult to maneuver and required makeshift darkrooms full of dangerous chemicals to be towed by horse-drawn wagons. As a result, the talent of sketch artists like James R. O’Neill became a valued commodity. His finely detailed illustrations filled weekly newspapers, whose readers demanded coverage of the bloody conflict. O’Neill would also earn the distinction of being the only war correspondent killed in action during the War for the Union.

James Richard O’Neill emigrated from Ireland to North America in 1833 with his family while still an infant. After first arriving in Quebec, his father, Charles O’Neill, relocated the family to Kenosha, Wisconsin, where the Irishman found work as the local lighthouse keeper. In 1854, James found work as a theater stagehand, designing and building sets, and later became a performer.

Shortly before the outbreak of war, O’Neill moved to Leavenworth, Kansas and soon made connections at the nearby U.S Army post at Fort Leavenworth. There, he was introduced to Frank Leslie, a staunch pro-Union supporter, and publisher of the high-circulation Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. O’Neill later embedded with Union troops, sketching soldiers and battle scenes that often depicted a more realistic portrayal of events than the staged and stiff portraits made popular by photographers such as Matthew Brady.

O’Neill became attached to the Union District of the Frontier under the command of General James G. Blunt in Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). O’Neill provided drawings of the major Union victory at the Battle of Honey Springs in the summer of 1863 as well as news reports of other engagements in the region.

On October 6, 1863, a large Confederate force under Captain William Quantrill ambushed Blunt’s unit near Baxter Springs, Kansas. Quantrill, a notorious guerrilla tactician didn’t believe in taking prisoners, ordered his “bushwhackers” to massacre the Union soldiers along with O’Neill and a military band. It’s worth noting that infamous outlaws Frank and Jesse James often rode with Quantrill and may have taken part in the bloodbath.

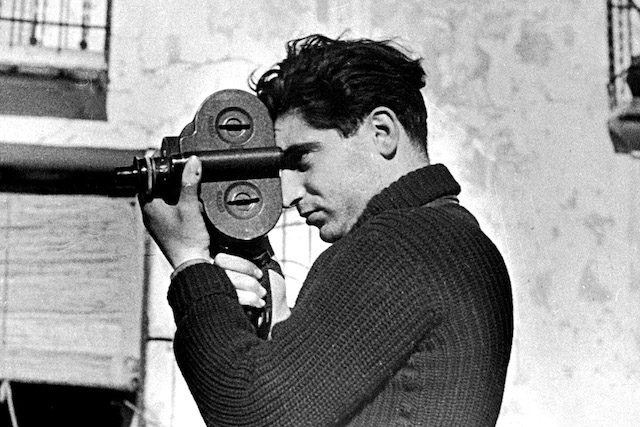

3. Robert Capa

Robert Capa is widely considered the greatest war photographer of all time. His graphic images captured the brutal realism of combat and would greatly influence the work of future generations. Ironically, his name was fake, the result of an alias concocted by a pair of unknown European photojournalists looking to make a name for themselves. It worked. Capa’s iconic, award-winning photos of D-Day and the Spanish Civil War are considered some of the greatest wartime images ever taken. Not surprising for a man who famously once said, “If the photo isn’t good enough, it’s because you’re not close enough.”

Born Andre Friedmann to Jewish parents in Budapest, Hungary in 1913, he later moved to Berlin and studied political science. He eventually fled the city following the rise to power of the Nazi party. Settling in Paris, he fell in love with a German woman named Greta Pohorylle (later Gerda Taro), who had also recently escaped the anti-semitism fervor gripping the country.

The couple soon began taking photos and selling them to news outlets, claiming to be the agent of the fictitious American photographer, “Robert Capa.” While covering the Spanish Civil War, they produced the best-known images of the conflict between the fascist regime of General Francisco Franco and Republican forces loyal to the democratically-elected Spanish Republic.

During World War II (and having fully adopted his invented moniker), Capa worked extensively for Life Magazine, including the landing of U.S. Marines on Omaha Beach. He also parachuted into enemy territory in Operation Varsity, taking part in the largest airborne mission in history. For his ground-breaking work, General Dwight D. Eisenhower awarded him the Medal of Freedom.

Capa went on to co-found Magnum Photos — the first co-op agency for worldwide freelance photographers. Shortly before his death, he intimated to friends such as Ernest Hemingway, John Huston, and Humphrey Bogart that he wanted to work on new film projects and was done reporting from combat zones. Nonetheless, Capa accepted an assignment to cover the First Indochina War and was killed after stepping on a land mine while embedded with a French regiment in Thái Bình Province.

2. Gerda Taro

She worked under the professional name “Gerda Taro“ — naming herself after the Japanese artist Taro Okamoto and Swedish actress Greta Garbo — and was also known as “Little Red Fox” for her ginger hair and diminutive stature. After fleeing Nazi Germany, Taro would emerge as a pioneering photographer and is credited as the first female journalist killed while covering a war from the frontline.

Greta Pohorylle was born on August 1, 1910, in Stuttgart, Germany to Jewish parents. She became politically active early on, opposing the rise of the National Socialist German Workers Party (aka the Nazi party) and was arrested and detained on charges of distributing propaganda.

She eventually moved to Paris where her career blossomed after her business and personal involvement with the man that came to be known as Robert Capa. As Taro, she initially began working as his assistant during the Spanish Civil War but soon developed a style uniquely her own, capturing deeply moving photographs. In 1937, she suffered fatal injuries when an out-of-control tank crashed into a car she was traveling in near Madrid. Her death devastated Capa for the rest of his life.

On what would have been her 27th birthday, thousands of mourners attended her funeral at Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris. The French landmark is the final resting place of several other notable trailblazers, including Oscar Wilde, Édith Piaf, Chopin, Moliere, and Isadora Duncan. Several years after her death, it would be discovered that Taro had taken a significant amount of images mistakenly credited as Robert Capa’s early work.

1. Sean Flynn

He could have done anything with his life. And so he did. As the only son of legendary movie star Errol Flynn and French actress Lili Damita, Sean Flynn inhabited a world most can only dream about. But he was also an enigma with a restless soul. Impossibly handsome although typically shy, he went looking for danger but not attention. He would also experience something his famous father never did: real bullets in a real war zone.

His parents divorced shortly after he was born, and Flynn and his mother moved to south Florida — far away from the wicked, wicked ways of Hollywood. He briefly attended Duke University but felt out of place and dropped out after only a semester. Unable to hide from his good looks and celebrated last name, he agreed to star in The Son of Captain Blood, an exploitative sequel of the film that launched Errol Flynn’s career three decades earlier. The young heartthrob would compile a string of similar credits, going for the quick cash grab before accepting an assignment with Paris-Match to report on the Vietnam War.

After landing in Saigon in January 1966, he soon fell in with a band of other renegade journalists, including Tim Page, John Steinbeck, Jr., and Michael Herr. Flynn took on dangerous assignments with the Green Berets and other Special Forces units and didn’t hesitate to parachute or descend by helicopter into a hot landing zone. He dedicated himself to becoming better at his craft with his Leica M2 camera, and provide an unfiltered account of the savage violence of this especially brutal war. His raw photographs were published by Time-Life as he continued to push the envelope, going deeper on field missions and taking increasingly more risks.

In 1967, Flynn traveled to Israel and covered the Six Day War. He returned to Vietnam the following year as the Tet Offensive raged throughout South Vietnam, signaling a turning point in the conflict. Dubbed “The First Television War,” freelancers had unprecedented (and uncensored) access to document history unfolding in real time. The excitement and danger were palpable. Cheap and plentiful opium added to the allure. Page, who was wounded five times and nearly killed twice, later wrote: “It was a hard war to leave, a constant thrill surrounded by a coterie of brothers, bonded by experience and the heady rush of revolution and rock and roll that was the 1960s. There was nothing back in the world to match it.”

The incursion of North Vietnamese forces into neighboring Cambodia eventually led to a heavy American military presence there — as well as reporters covering the action. Flynn had been steadily compiling hours of film for a documentary he was making about his wartime experiences. On April 6, 1970, he and CBS cameraman Dana Stone set out on red Honda motorcycles deep into Viet Cong (VC) occupied territory to shoot more footage. They were never seen again.

It’s believed the men were kidnapped by VC soldiers and then handed over to the Khmer Rouge before being executed. Despite various attempts over the years by family, friends and the U.S. government, the remains have never been found. Flynn was declared legally dead in 1984.

4 Comments

Nice list. I wish you had listed Larry Burrows and the three other journalists whose helicopter was shot down in Viet Nam on February 22, 1971. His photojournalism brought the war home to Americans.

Thank you, Karen. I agree with you with regards to Larry Burrows. Tremendous talent. However, it’s my understanding that he was killed in Laos — but his work certainly helped define the Vietnam War.

Content was fascinating, but a sticking point here: it’s NOT the University of Indiana! It’s INDIANA UNIVERSITY. Thanks.

CJB, thank you for the clarification — duly noted.