It’s called the ultimate sacrifice — soldiers who put on a uniform and die fighting for their country. Like anyone else serving in the military, famous athletes aren’t immune to the inherent dangers of combat.

From World War I to present-day conflicts, here’s a list of those who went to war and never came home.

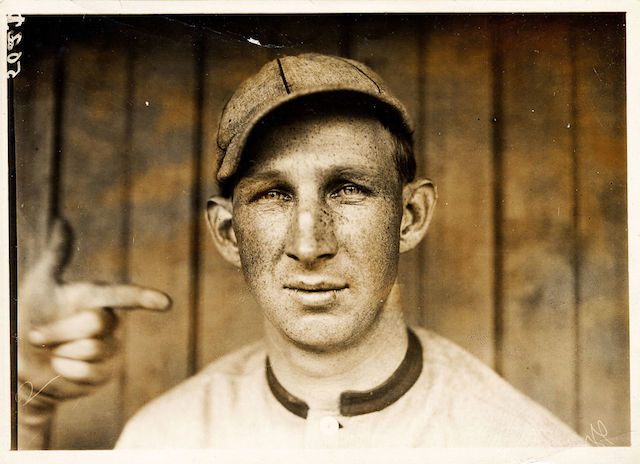

10. Eddie Grant

For over three decades, a bronze plaque hung prominently on the centerfield fence of the Polo Grounds in New York City, honoring Eddie Grant with the inscription, “Soldier-Scholar-Athlete.” Both the original sign and legendary field are long gone, but Grant’s legacy continues to endure as the most prominent (and first) Major League Baseball player to be killed in action in World War I.

Born on May 21, 1883, Edward Leslie Grant was indeed a man for all seasons. He played both basketball and baseball while attending Harvard, where he later earned a law degree. Grant would eventually become a practicing attorney, but his skills on the baseball diamond earned “Harvard Eddie” his greatest notoriety. The third baseman enjoyed his best season in 1909, batting .269 as Philadelphia’s leadoff hitter and finishing second in the National League with 170 hits.

He played in a total of 990 big league games during the “dead-ball era” with the Cleveland Indians, Philadelphia Phillies, Cincinnati Reds, and New York Giants. Regardless of his uniform, the erudite infielder refused to yell the traditional, “I got it,” when chasing a fly ball, preferring the more grammatically correct, “I have it.”

Grant enlisted in the U.S. Army shortly after America’s entry into WWI, expressing to a friend, “I believe there is no greater duty than I owe for being that which I am — an American citizen.” He joined the 307th infantry regiment of the 77th Division and quickly rose to the rank of captain.

On October 5, 1918, he led a patrol into the Argonne Forest near Verdun, France, in search of the “Lost Battalion,” a unit that had gone missing a few days earlier. German artillery inflicted heavy Allied casualties, including Captain Grant, who died from a shell explosion. His remains were laid to rest at the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery in France, along with more than 14,000 other American soldiers.

9. Luz Long

Adolf Hitler had intended to propagandize the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin as a showcase of Aryan superiority. Jesse Owens had a different plan. The African-American from Ohio State would eventually win four gold medals while breaking or equaling nine Olympic records and setting three world records. He also found sportsmanship from an unlikely source: Germany’s long jump champion, Luz Long.

Carl-Ludwig Hermann “Luz” Long represented the ideal personification of Nazi ideology: tall, blonde, blue-eyed, and confident. As the European record holder in the long jump, Long stood poised to capture the gold medal on home soil. During the preliminary rounds, the 21-year-old law student from Leipzig met all expectations by breaking the Olympic record to the delight of a frenzied, packed stadium. Meanwhile, Owens struggled. He fouled on his first two attempts before registering a legal qualifying mark on his last jump, advancing to the finals.

A somewhat apocryphal tale later emerged that Long assisted his American rival by advising the well-seasoned jumper (and world-record holder) to adjust his takeoff position. Regardless, the record books show that the two men engaged in a thrilling, back-and-forth competition won by Owens with a leap of 26 feet, 4 inches in a new Olympic record. Long took the silver medal and was the first to congratulate Owens on his triumph. Afterward, the men posed together for photos and walked arm-in-arm out of the arena, angering the Führer and his delusional notions of racial supremacy.

Following Germany’s invasion of Poland to kickstart World War II, Long joined the Army, holding the rank of Obergefreiter. He later died in July of 1943 from wounds suffered during the Allied invasion of Sicily at the Battle of St. Pietro.

Years later, Owens wrote about his fellow competitor: “You can melt down all the medals and cups I have…and they wouldn’t be a plating on the 24-carat friendship I felt for Luz Long at that moment.”

8. Jack Lummus

The mere mention of Iwo Jima serves as a chilling reminder of the hardship and sacrifice experienced by Marines during WWII. According to Lieutenant General Holland M. Smith, “Iwo Jima was the most savage and the most costly battle in the history of the Marine Corps.” The siege also produced no shortage of heroism by American soldiers. Jack Lummus was one of those men.

The standout athlete from Ennis, Texas, excelled as a two-sport star at Baylor University, where he played football and baseball. Following graduation, the slugging outfielder signed a contract with the minor league Wichita Falls Spudders and later caught the pigskin as a rookie for the New York Giants in 1941.

On December 7 that year, a packed crowd of 55,000 at the Polo Grounds watched a football game between the Giants and their crosstown rivals, the Brooklyn Dodgers (yes, both were also the names of baseball teams, too). Meanwhile, 5,000 miles away, Japanese forces launched a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor that would alter the course of history. Like many young men at the time, Lummus heeded the call of duty.

He enlisted in the Marine Corps and took officer’s training at Quantico, VA, earning a commission as a First Lieutenant. In February 1945, the ex-jock joined the first wave of troops to land at Iwo Jima, where his platoon engaged in intense fighting against well-entrenched Japanese forces on the rocky, volcanic island.

While leading his men during a firefight, Lummus suffered shrapnel wounds from a grenade but managed to knock out three enemy positions. He continued the assault without taking cover but stepped on a land mine and shredded both legs. While lying on the ground, he urged the platoon to keep fighting before being taken to a field hospital. There, as he lay dying, he told the doctor, Thomas M. Brown, “Well, doc, the New York Giants lost a mighty good end today.”

For his gallantry and leadership displayed during the battle, Lummus posthumously received the Medal of Honor. His remains were initially laid to rest in the Marines Fifth Division Cemetery but later moved to the Texan’s home cemetery in Ennis.

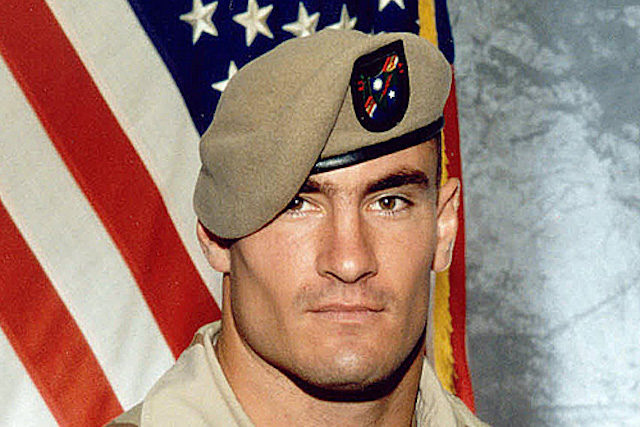

7. Pat Tillman

Pat Tillman seemed to have it all. The charismatic football star with flowing long hair and chiseled good looks had been recently offered a three-year contract extension with the Arizona Cardinals valued at $3.6 million. But the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001 changed everything. The NFL would have to wait.

After a successful college career at Arizona State, the All-Pac 10 linebacker made Arizona’s roster in 1998 as a safety. He played in 16 games (10 as a starter) his rookie year and steadily improved to become one of the team’s leading tacklers and a big fan favorite. Nonetheless, Tillman decided his talents were needed elsewhere.

Not unlike Pearl Harbor from a past generation, 9/11 became a motivating factor for young men to join the military. Both Tillman and his younger brother Kevin enlisted in the Army, and took part in the initial wave of Operation Iraqi Freedom. The siblings returned to the U.S. to attend Army Ranger School and after graduating were redeployed back to the Middle East.

While stationed at Forward Operating Base Salerno in Afghanistan, Pat Tillman was killed on April 22, 2004. Military officials initially stated that he died in an ambush by enemy combatants outside of the village of Sperah near the Pakistan border. The report, however, proved to be false. Subsequent investigations by the Department of Defense and the U.S. Congress eventually determined that his death had occurred due to friendly fire.

Tillman’s biography is complex. He was both an atheist and held particular anti-war views — but his demise warrants a closer examination and nothing less than the truth. The Pentagon and U.S. Government were ultimately exposed for attempting to spin an unpleasant casualty into a PR stunt. Tillman’s family, justifiably, were livid. The American soldier had sacrificed his life with honor —and not to be used as a patriotic prop or an instrument for political gain.

6. Gunnar Höckert

American Civil War General William Tecumseh Sherman famously once said, “War is Hell.” As such, the often over-looked Winter War between Finland and Russia represented frozen Hell in a region where temperatures reached 45 degrees below zero. The brutal conflict would also claim the life of the 1936 Olympic 5,000 meter champion, Gunnar Höckert.

In the history of Finnish champions, a pedigree that includes Olympic heroes Paavo Nurmi and Lasse Viren, Höckert’s extraordinary 1936 season firmly solidified his legacy forever. The Helsinki runner defied the odds by defeating teammates lmari Salminen (the 1936 Olympic 10,000 meter champion) and Lauri Lehtinen (the defending Olympic 5,000 meter champ and world record holder). Höckert continued his dominant form later that year by establishing world records for 3,000 meters and two-miles and equaled the all-time best for 2,000 meters — all in just three weeks.

By late November of 1939, Höckert shifted his focus to defending his homeland against invasion. Soviet leader Joseph Stalin had decided Mother Russia needed more land and unleashed his Red Army across the Finnish border near the Karelian Isthmus. The Finns, hopelessly outnumbered and outgunned, put up a surprisingly stout resistance, relying on guerrilla tactics as well as help from the punishing extreme cold weather. Fighting with a reserve unit, Höckert died on February 11, 1940 — one day shy of his 30th birthday.

Shortly afterward, the Nordic country ceded 11 percent of its territory to the Soviet Union as part of the Moscow Peace Treaty. It’s with noting, however, in only three months of fighting, Russian troops suffered over 300,000 casualties compared to 65,000 losses for the Finns.

5. Billy Fiske

In many ways, the extraordinary life of Billy Fiske reads like a Hollywood movie. He became the youngest Olympic gold medalist ever as a 16-year-old while competing in the bobsled at the 1928 Winter Olympics. He went on to establish the first ski resort in Aspen, Colorado, and also raced cars at the 24 hours of LeMans. The popular Fiske frequently hobnobbed among British aristocracy and later married the ex-wife of the Earl of Warwick. But his thrill-seeking adventures eventually met a tragic ending as the first American airman killed in combat during WWII.

William Meade Lindley Fiske III was born on June 4, 1911, in Chicago. The son of a successful international banker, he attended private schools in Europe where he developed an affinity for alpine sports. Following his Olympic triumph at St. Moritz, the daredevil won again at Lake Placid in 1932 and served as the U.S. flag bearer.

At the outset of World War II, Fiske set his sights on becoming a fighter pilot. America’s neutrality, however, kept him grounded. Undaunted, he used his well-heeled connections to forge official documents and pretended to be Canadian. Despite his athletic notoriety, it worked. He gained acceptance into the Royal Air Force (RAF) and reported for flight training in England.

Meanwhile, Nazi aggression continued barreling its way across Europe. A monumental showdown in the Battle of Britain awaited. Fiske joined the infamous No. 601 Squadron (“Millionaires Squadron”), testing his adept skills inside the cockpit of a Hawker Hurricane. He flew his first of several sorties beginning in late July of 1940 and eagerly engaged the relentless Luftwaffe attacks.

Fiske’s squadron chalked up several kills, such as German Junker Ju 87 Stukas and Messerschmitt Bf 110s. But on August 16, 1940, Fiske’s luck ran out. A German bullet pierced his fuel tank, creating a fire onboard the aircraft. The American managed to land the plane at the RAF airfield in Tangmere but suffered severe burns to his hands and ankles. He would die the next day from surgical shock at St. Richard’s Hospital in Chichester, West Sussex.

On July 4, 1941, the Secretary of State for Air, Sir Archibald Sinclair, unveiled a plaque in the crypt of St. Paul’s Cathedral to Fiske: “An American Citizen, Who Died That England Might Live.”

4. Foy Draper

Without question, Jesse Owens’s star shined brightest during the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin. The legendary athlete captured his fourth and final gold medal during a world-record performance in 4×100 relay that also featured teammate Foy Draper (second from the right in the above photo). The California speedster, running the 3rd leg, not only helped defeat Germany’s sprinters on the track but later bombed Nazi targets in North Africa during the Second World War.

Before the Olympics, Draper attended the University of Southern California, where he tied the world record for the 100-yard dash and won the IC4A (Intercollegiate Association of Amateur Athletes of America) title at 220 yards. He capped his stellar career with the relay triumph, joining Owens, Ralph Metcalfe, and Frank Wycoff in a record-setting time that went unbroken for 20 years.

Draper enlisted in the Army Air Corps in 1940 and later joined the 97th Squadron, 47th Bombardment Group, as a bomber pilot. On January 4, 1943, he took off in a twin-engine A-20 “Havoc” to take part in the Battle of Kasserine Pass. The plane never made it. Captain Draper and his two crewmen, SSgt. Kenneth Gasser and SSgt. Sidney Holland were reported missing — presumably shot down by enemy aircraft.

The Olympian’s memory is honored at the North African American (ABMC) Cemetery and Memorial in Tunis, Tunisia

3. Bob Kalsu

During the tumultuous 1960s in America, the Vietnam War divided the nation. Top athletes weren’t immune from the polarizing turmoil taking place from college campuses to Olympic arenas. But for Buffalo Bills rookie Bob Kalsu, his decision of whether or not to serve never wavered.

James Robert Kalsu was born on April 13, 1945 in Oklahoma City. He went on to become an All-American tackle for the University of Oklahoma on an Army ROTC scholarship, and later, the Bills selected him in the eighth round of 1968 NFL/AFL draft. As a rookie offensive guard, he started nine games and earned the team’s rookie-of-the-year award.

Following the season, most pro players eligible for military service chose to join the reserves and avoid combat duty. Not Kalsu. He insisted on honoring his promise of engaging in active military duty. “I gave ’em my word,” Kalsu said. “I’m gonna do it.”

The newly commissioned First Lieutenant arrived in South Vietnam in November 1969 as a part of the artillery unit attached to the 101st Airborne Division. He took command of a platoon at Fire Support Base Ripcord in the A Shau Valley, an area just south of the DMZ under bombardment from heavy mortar and rocket fire by the North Vietnamese Army (NVA).

On July 21, 1970, Kalsu suffered fatal injuries from an enemy mortar shell explosion; the attack occurred just hours before his wife, Jan, gave birth to their second child back home in Oklahoma. Kalsu’s death marked the only instance in which an active professional football player died fighting in the Vietnam War.

2. Walter Tull

Near the entrance to the Faubourg d’Amiens Cemetery in northeast France, stands the Arras Memorial. The name of a British soldier, Tull W.J.D., is inscribed there as one of 34,785 fallen soldiers whose bodies were never recovered in WWI. As the grandson of a former slave, Tull’s story is both Dickensian and Byronic. He battled adversity, racism, and inequality his entire life to emerge as a trailblazer on both the playing field and battlefield.

Walter Daniel John Tull was born in Folkestone, Kent, on April 28, 1888 to Daniel Tull, a carpenter from Barbados, and a local English woman, Alice Elizabeth Palmer, who gave birth to five children. By the age of nine, both his mother and father had died. As a result, Walter ended up at an orphanage in Bethnal Green, London. The sudden loss of his parents forced him to cope with the first of many severe hardships, forging a steel-plated resolve that would serve him well throughout his life.

Tull adhered to the strict discipline in the church-run facility and worked as an apprentice in a printing shop. He also found refuge in sport and especially excelled in football (that’s soccer, to our American readers), playing halfback for Clapton F.C., one of the top amateur clubs in London. In 1909, he signed with First Division Tottenham Hotspur and became only the third professional black football black player in Britain. The color of his skin, however, created a torrent of racial abuse that eventually led to his departure from the North London side. Despite the bitter disappointment, he experienced a major career breakthrough following a transfer to Northampton Town, emerging as the Cobblers most popular player over the next three seasons.

In Britain during the summer of 1914, the outbreak of war affected an entire generation. Tull joined the 17th Battalion, Middlesex (Duke of Cambridge’s Own) Regiment — better known as the “Football Battalion.” He smoothly transitioned from tackling to soldiering with typical self-assurance and saw rapid promotion during training in England. But nothing could have prepared him for the Hell that awaited. Allied troops would soon encounter the very worst elements of trench warfare: constant shelling, poisonous gas, horrible weather, and squalid living conditions plagued with vermin and lice.

Having impressed senior command with his leadership qualities and calm under pressure, Tull reported Officer Cadet Training School in Gailes, Scotland. Upon arrival, he encountered institutional racism from the instructors and prejudiced behavior by cadets. As always, Tull persevered and ultimately received his commission. While in Ayrshire, he met up with his older brother Edward, now living in Glasgow as a successful dentist.

The siblings planned out a post-war future — and one with a bright outlook after Walter signed on with Glaswegian powerhouse, Rangers FC. But first, 2nd Lieutenant Tull made history in another arena, becoming the first black or mixed-race officer in the British Army to lead white troops in combat. On March 25, 1918, Tull spearheaded an attack on German trenches near the small village of Favreuil, France, and met heavy machine gunfire. The badly outnumbered British troops were forced to withdraw, but as Tull tried to cover their retreat, a bullet struck him in the neck. His body would be forever lost to no man’s land.

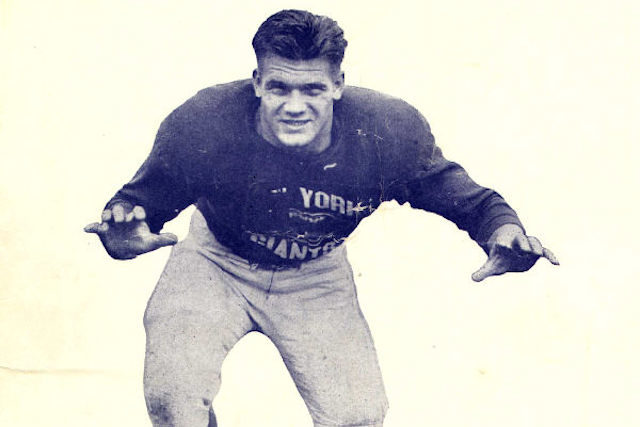

1. Al Blozis

He stood 6-foot-6 and weighed 250 pounds of solid muscle. His larger-than-life persona warranted three nicknames: “The Human Howitzer,” “Jersey City Giant,” and “Hoya Hercules.” He broke several world records in the shot put and later became an All-Pro defensive end for the New York Giants. And had it not been for WWII, Al Blozis appeared destined for athletic immortality.

As the son of Lithuanian immigrants, Blozis understood the importance of hard work while growing up in the blue-collar town of Jersey City. He became a standout multi-sport athlete at Dickinson High School, but his size and strength made him especially dominant in the throwing events. By the end of his senior year in 1938, he established an astounding 24 high school records and accepted an athletic scholarship to Georgetown University.

Blozis continued his assault on the record books and became a fan favorite at Madison Square Garden, where crowds flocked to see the modern-day Samson. His followers included renowned New York Times sportswriter Arthur Daley, who called him “the most magnificent physical specimen that these eyes have ever seen.” Blozis also starred on the gridiron, leading the Hoyas to 23 consecutive wins and an appearance in the Orange Bowl.

Naturally, the nation’s top thrower set his sights on competing in the Olympics. Worldwide conflict, however, would lead to the cancellation of both the 1940 and 1944 games. The American could at least take solace that his personal best measured more than four feet better than the 1936 Olympic shot put champion (and future SS Waffen Officer), Hans Woellke.

After graduating from Georgetown in 1942 and with American troops now fighting overseas, Blozis made several attempts to enlist but was turned him away due to height restrictions. The rejection hurt. Similar to other celebrity sportsmen, military brass offered him a gratuitous, stateside commission. Blozis refused. He wanted to fight. Instead, he signed with the Giants and enjoyed immediate success as the strongest (and most intimidating) player in the NFL.

He spent the off-season lobbying military officials to lift their size ban before the Army finally accepted him. While training at Officer Candidate School at Fort Benning, Georgia, Blozis added to his legend by tossing a grenade nearly 95 yards. Before shipping out to Europe, Blozis joined his Giant teammates in 1944 NFL Championship against the Green Bay Packers at the Polo Grounds. It would be the last game he ever played.

The Army assigned him to the 110th Regiment, 28th Infantry Division, near the Vosges Mountains in the Alsace region of France. During an evening snowstorm on January 31, 1945, Lt. Blozis went looking for two soldiers from his platoon after the men had failed to return from a scouting mission earlier in the day. Despite facing a well-entrenched enemy, pitch-black darkness, and freezing conditions, he set out alone to find them. The towering champion never returned.

Scuttlebutt soon emerged of soldiers hearing German machine-gun fire in the location where Blozis was last seen. The Army initially listed him as missing, but by the beginning of April, military officials declared him KIA.

In addition to receiving the Bronze Star and Purple Heart, Blozis compiled several other posthumous football accolades, including the NFL All-Decade Team, Giants Stadium Ring of Honor, the College Football Hall of Fame and the National Track and Field Hall of Fame. The Giants retired Blozis’ uniform number 32, and True Comics published a special sports issue in 1946, commemorating the real-life story of “The Human Howitzer.”

NFL Hall of Famer Mel Hein had this to say about his former teammate: “If he hadn’t been killed, he could have been the greatest tackle who ever played football.”

Today, a simple white cross memorializes 1st Lt. Al Blozis at the Lorraine American Cemetery in Saint -Avold, France. The serene, lush grounds of Europe’s largest U.S. WWII memorial sits peacefully in a region now known as the Grand Est (The Big East), commemorating its rich history and a fitting tribute to a true American hero.

1 Comment

You forgot Nile Kinnick. Won the Heisman in 1939, died while flying a training mission during WW2.