The Iron Age is generally accepted to have been the final age before solid, written history in the development of human society. This doesn’t mean that a society arriving at Iron Age was necessarily a sign of progress. That’s just one of the many counterintuitive things to be learned about this period, or rather these periods. While it’s usually associated with Ancient Greece in particular, we’ll be traveling the globe and back and forth through time in this study. There are a lot of different perspectives on what it was like for a society when the 26th element of the periodic table was on top.

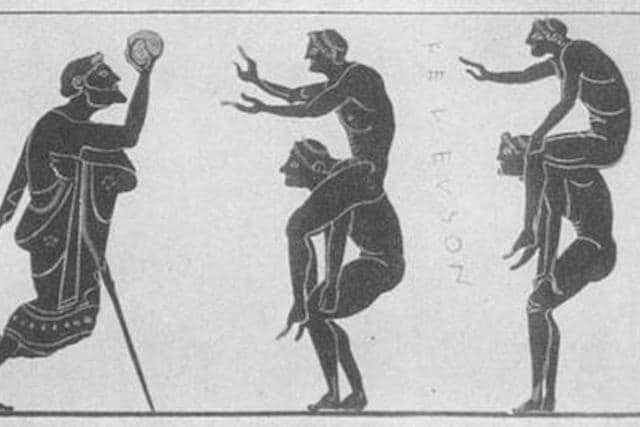

10. Greece

Human history is usually laid out for us as a gradual ascent to give the impression civilizations will adopt one practice then give it up when something more desirable comes along. So it’s natural to assume Greece moved from a Bronze Age that began in 2800 BC to an Iron Age because of an inherent superiority of iron in combat. In truth, no. Bronze is both stronger than wrought iron and less corrosive. It was also easier to smelt since copper and tin melt at much lower temperatures than iron ore (roughly 1,000 degrees F vs about 1,500 degrees). So it is that the Early Iron Age of Greece also became known as Greece’s Dark Age.

Around 1200 BC, Greece’s population density plummeted, largely because of famines. Entire cities were abandoned, Athens being the exception. Raising livestock replaced more specialized occupations, and many who raised cattle had to downgrade to raising pigs instead. Turning from the combination of copper and tin that were used to make bronze to iron was more out of necessity because iron was more plentiful. It was thus one of the first known instances of quality having to give way to cost effectiveness. Considering that the Greek Iron Age is estimated to have ended around 800 BC, that was a long period of economic troubles.

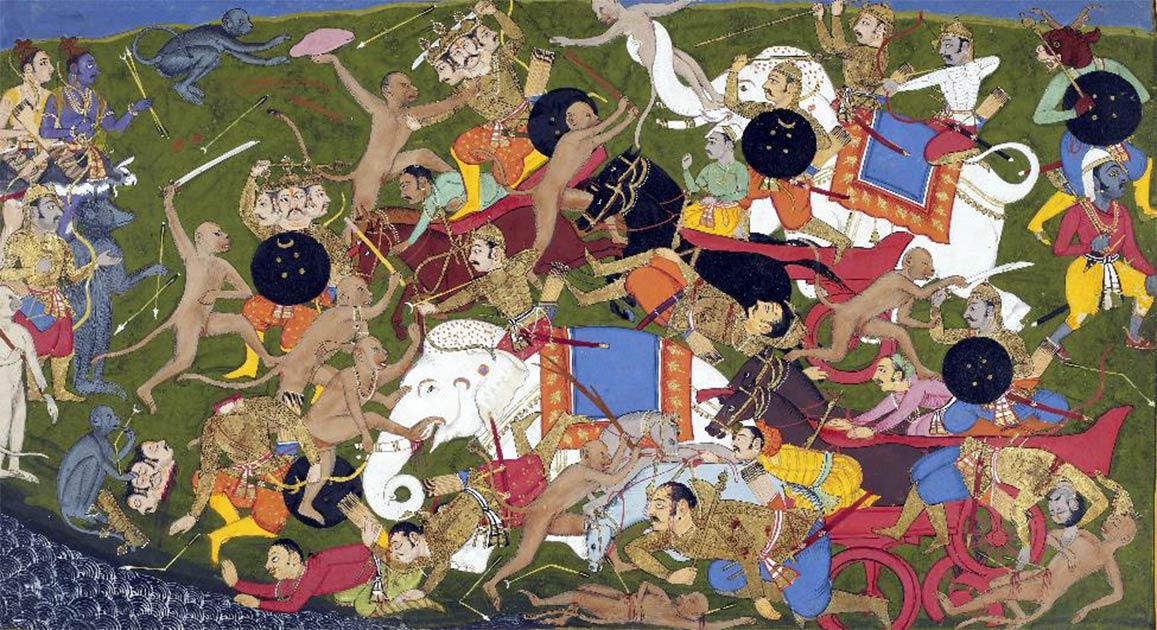

9. India

Since the Indus Valley was home to settlements such as Bhirranna which date back to circa 7500 BC, populations that would one day merge into India had plenty of time to develop metallurgy of their own. The Bronze Age has been reported to have begun around 3000 BC, which is early indeed. Despite this, early estimates put the beginning of India’s iron age at 1000 BC, a couple centuries after Greece’s, and claimed that it was due to a shortage of tin. That turned out to be wrong when later discoveries in Karnataka, India in the Indian peninsula put the date at 1500 BC. Then further to the south, discoveries in the state of Tamul Nadu put it at an extremely early 1900 BC. It’s generally accepted that India’s Iron Age lasted until 200 BC, indicating that it lasted more than twice as long as Greece’s even with the later start date.

So why did India turn to iron so much earlier than Greece or even than material conditions demanded? It turns out that it might have been accidental. Archaeological findings in the Indus Valley area revealed a number of objects were smelted with a combination of iron and copper ores. It’s quite possible then that the iron was introduced as a flux (i.e. purifying or cleaning element) and turned out to be worthwhile to Ancient Indian metallurgists. There’s considerable uncertainty because scientific advancements in Ancient India remain significantly understudied.

8. Scandinavia

Norway and Sweden are both enough exporters of iron ore, with Sweden producing so much that it was a massive boon to Axis arms production during World War II. Yet Scandinavia didn’t have its iron age until a relatively late 500 BC. It was especially odd because Scandavian communities had been relying on imports for their bronze before and only turned to their rich local supply when the flow of raw materials stopped. Even more curiously, at first the Scandinavians needed to import iron implements too. When at length they began to start thinking locally, they got much of their iron from clumps of ore found in bogs instead of digging mines and quarries.

Unlike Greece and India which ended their Iron Age phases still in the BC period, Scandinavia’s lasted until 800 AD. It came to a very definite end with the beginning of the Viking Age. Not because Vikings abandoned iron or anything of the kind. It’s that, as indicated by other articles on TopTenz, Viking history is very well-documented and thus was distinct from the historically sketchy iron age.

7. China’s Unusual Ore Source

While Scandinavians were overlooking the iron resources at their feet, Chinese metallurgists were in a sense looking to the stars for their raw materials. That is to say, when the Chinese Iron Age began circa 1600 BC to 1100 BC during the Shang Dynasty, the first metals that the smiths put in the forge came from meteors. This was not unprecedented, as a necklace of meteor beads was found in Egypt that dated to 5000 BC, but the fact a number of blades from the ancient Chinese Middle States confirms it was a much wider practice. However, all through this period bronze was still in common usage.

It wasn’t until the Shang Dynasty gave way to the Zhou Dynasty around 1044 BC that the Chinese Iron Age truly began. It was also during this period that meteoric iron was replaced by the even cheaper alternative pig iron. In 206 BC, the Han Dynasty came in and nationalized iron production throughout the Middle Kingdom. During the resulting period of innovation, Chinese metallurgists invented steel, although this technology was largely lost for a long time during the Tang Dynasty. It just goes to show that no way of life, even a basic manufacturing technique, is necessarily permanent.

6. Central African Worship

African communities from antiquity break the pattern we’ve been establishing because there’s no surviving evidence that any of them went through bronze ages. It was straight from polished stone to iron. The earliest evidence of ironwork comes from the Bantu people on the Nigerian Plateau from around 1000 BC. There was also evidence that the city of Merou on the Nile was installing them in roughly the same period. By coincidence, tradesmen from Europe were also bringing the technology to the African continent at the time. It was definitely an idea whose time arrived with full force.

African communities took to blacksmith with zeal. Not only did iron become so central to their societies that, for example, in the Congo some tribes used iron throwing knives as literal currency, meaning people could feasibly be held up for the very objects they could use to protect their property. Some tribes would elevate the blacksmiths in nearly as high of esteem as the king. Indeed, numerous stories circulated in Central Africa of blacksmithing princes. Frankly, to us learning a skill that serves a community does sound like a more sensible reason to be given authority than birthright. However justified that love of blacksmiths was, the most defined ending of the iron age in Central Africa was around 1000 AD when there was a boom of copper, which became the main export for the region.

5. Britain’s Iron Ages

Like Scandinavia, the British Isles seemed to turn from bronze to iron because they were forced to by disrupted trade routes circa 800 BC. Unlike many nations, their iron age was something of a golden age. Pottery greatly improved with the introduction of the pottery wheel, new crops came in and allowed for crop rotation, and previously disparate groups began to conglomerate into structured communities. Most people don’t imagine chariots when they think of any period in British history but those were a common weapon at the time.

While the iron age in the regions that would become England and Wales firmly ended in 43 AD with their complete conquest by Emperor Claudius, the Roman legions were never able to conquer Scotland. Consequently its iron age continued on until after the Western Roman Empire, roughly until 500 AD. Since the Roman Empire has been conflated with civilization in Europe, this might give the impression the Scots (or Picts as they were known then) were just a crude rabble. In fact during that time elaborately designed blacksmithery and colorful, patterned clothing were in fashion, indicating the Picts had a rather refined culture of their own that didn’t need to be influenced by Roman conquest, thank you very much.

4. North American Abandonment

Picturing tribes in North America, stone arrowheads probably come to mind before any sort of iron tool. This despite the fact that indigenous tribes were estimated to have developed metallurgy around 5000 BC, which was early indeed. However, the tools were defective copper tools, and for a time the tech was abandoned and they went back to stone. It was only when experiments with copper-iron alloys produced more durable implements that metalworking became viable. However, no artifacts have been found which indicate any community ever developed bronze.

Judging by surviving iron forges, it would appear that Ohio was a center for blacksmithing in what became North America. The area by no means had a monopoly on metalworking, with iron relics being found throughout Etowah burial mounds in Georgia. Even up in the Inuit areas, meteoric iron was fashioned into knives just as it was over in China.

All of which makes the next entry a little stranger.

3. South America

To anyone with even a passing familiarity of Conquistadors in South America, the fact there was a lot of gold to steal is no surprise. The Andes Mountains had been yielding rich hauls of gold since roughly 3000 BC, in some cases with so little trouble that there wasn’t even a need to dig mines. The earliest known mine is a Chilean copper mine that dates back to roughly 500 BC. However, there’s no surviving evidence that any South American civilization ever went through an iron age prior to invasion.

That’s not to say that there was no mining of iron ore in South America prior to the 1500s. There is a Nasca mine a few hundred miles south of Peru’s capital Lima that was first dug as early as 100 AD and which yielded an estimated 3,700 tons of iron ore. That might sound like a lot, but on the other hand it was over as many as 1,400 years. The ore was really only used as pigment for paint. How heavy industrial blacksmithing never made its way from North America to South America will likely remain a mystery.

2. Japan’s Mixed Up Timeline

We’ve seen a few variations from the standard “bronze age becomes iron age” model, but Japan still found a new way to break the mold in that it began its iron age before there was any sort of bronze age. This may be hard to imagine for modern readers since we’re so used to Japan being an Asian superpower, but Japan was colonized relatively late compared to mainland Asia. So it was some time before Japanese settlers were able to develop metallurgy of their own, and so during the early Yayoi Period which began around 300 BC, they had to rely on iron imports from Korea for their tools.

To further show how much more significant iron was for the beginning of Japanese society, when bronze goods began to arrive, it was overwhelmingly only for ceremonial objects. For example there were bronze spears and swords that were so heavy that they were no more practical in combat than the bronze temple bells. So it was until around 300 AD when the iron age ended as the Yamato Clan began to form a centralized government for Japan which recorded history more thoroughly.

1. Iron Currency

The TopTenz article on the ancient Greek city-state of Sparta mentioned how the lawgiving king Lycurgus decreed that the city use iron currency. The ostensible reason was that it encouraged Spartans to value strength and hard living over material wealth by making the metal both cumbersome and often too corrosive to be handed through a family line. There’s some debate over whether that was true, or if Sparta just happened to have an iron mine and was too distrusting of its neighbors to want to be reliant on their mines for currency. Whatever the case, it was sufficiently effective that there is evidence other cities tried it as well, albeit for nowhere near as long as Sparta did.

It turns out iron currency was also practiced in Great Britain as well. Julius Caesar himself wrote about how the locals were using iron bars for currency in 54 BC. In 1856, 150 ancient iron bars were accidentally discovered by workmen near Worcestershire, UK. Surviving bars weigh roughly half a kilogram, or one pound. The pun on the term for British currency seems to be a coincidence.

Dustin Koski edited and contributed to the horror comedy Return of the Living, a post-apocalyptic story of a ghost seeing the first living being in centuries.