When Adolf Hitler’s Nazi Germany declared war on the United States, his hatred for America was visceral. So when his chief of military intelligence, Admiral Wilhelm Canaris of the Abwehr, proposed a means of striking in America’s heartland, crippling its industry and terrorizing its people, he approved immediately. The plan was to recruit German men, former residents of the United States, to conduct a campaign of terror bombings targeting America’s infrastructure including transportation facilities, manufacturing plants, electrical distribution grids, and other targets of opportunity. It was called Operation Pastorius, named for the founder of America’s first German settlement, Germantown, Pennsylvania.

The first team of bombers would be followed by a second, then a third, and support for the bombers would be drawn from Nazi sympathizers in America, according to the plan developed by Canaris and run by a deputy, Walter Kappe. Its agents were trained to identify and target Jewish owned businesses in American cities, which Hitler believed carried undue influence with the American government. Operation Pastorius was not a single wave of terror bombings, but a series of them calculated to cripple America’s ability to make war through the flexing of industrial muscle. It was betrayed by at least one of the agents involved, and J. Edgar Hoover took advantage of the betrayal.

10. The Germans planned a wave of terror in the Northeast and Midwest

German military planners of the Abwehr selected the primary targets for the first wave of Operation Pastorius. They included the hydroelectric plant at Niagara, which provided electrical power for much of the northeastern United States. The Hell Gate Bridge complex, a critical railroad link connecting New York to New England was to be bombed, disrupting freight and passenger traffic. America’s aluminum industry figured heavily in the target lists, which included a cryolite processing plant in Philadelphia (cryolite being essential in the smelting of the metal), and several aluminum plants in Tennessee, Illinois, and New York.

Railroad repair facilities and stations were targeted, as were locks crucial to the navigation of barges on the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers. During their preparation, the agents selected for Pastorius were trained in identifying and bombing targets of opportunity. They were to be selected for their economic value as well as terror effect, and included department stores and restaurants, railway depots, airports, subways, and places of public gathering. Abwehr planners envisioned the operation in effect for two years in the United States, with minimal communication between the agents and planners in Germany. The agents were trained to recognize emerging targets and act accordingly.

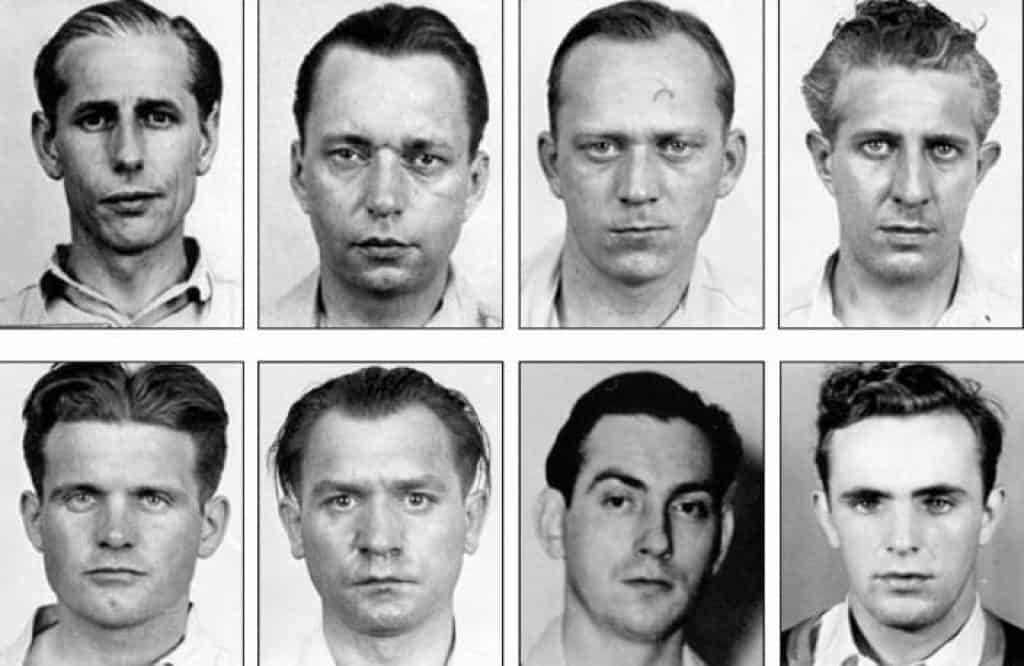

9. Eight agents were recruited and trained by the Abwehr

Originally, 12 men were recruited by the Abwehr, selected by Walter Kappe from lists of men who had been repatriated from the United States. Four quickly dropped out of the program, and eight were sent to complete three weeks of training at an Abwehr facility in April 1942. They were trained in the handling of demolition charges and timers, the manufacturing of bombs and munitions, and their placement for maximum effect. They also received training in target selection, small arms, and other aspects of espionage. The training was conducted at an Abwehr facility about 50 miles from Berlin, with some of the instruction provided by operatives of the Irish Republican Army working in concert with the Abwehr.

All of the men selected had lived in the United States for some time, and at least two were American citizens. Another two had served in the United States Army or National Guard. As they were trained, the Abwehr created life histories for each, giving them fictional backgrounds based on their American experiences, and the documents necessary to sustain the charade. Drivers licenses, birth certificates, passports, social security cards, and letters from friends and family were prepared for the men to carry during their mission in the United States. When the training was complete the men traveled to L’Orient in France, from whence the Kriegsmarine carried them to the America.

8. They were landed in the United States by two separate U-boats

Divided into two teams of four — one led by George John Dasch, the other by Edward Kerling — the agents were carried by U-Boats to the United States. The first to arrive reached Long Island near Montauk in the early morning of June 13, 1942. The team led by Dasch went ashore wearing German uniforms. The uniforms and the explosives which they brought ashore were buried near their landing point, to be retrieved later, and the four men walked to nearby Amagansett, where they boarded a Long Island Railroad train to New York, inconspicuous amongst the early morning commuters. By the time they arrived in New York their presence in America was known to the authorities.

The second team, led by Kerling, was deposited on Ponte Vedra beach near Jacksonville, Florida, going ashore in the darkness wearing swim trunks and German uniform caps. They arrived on June 16. They dressed on the beach, buried their explosives, and walked to a Greyhound bus station, where they caught a bus to Jacksonville. From there they traveled by train to Cincinnati, where they split into pairs, with two moving on to Chicago and the other two, including Kerling, traveling to New York. All eight agents were to reconnoiter their targets, and rendezvous in Cincinnati on July 4, 1942, to coordinate the bombings to ensure maximum terror effect.

7. The teams planned a campaign of sabotage to last two years

The teams went ashore carrying explosives for their first wave of bombings on targets assigned by the Abwehr. In Germany, Walter Kappe was already planning for additional teams to be sent to America, including himself. He planned to establish a headquarters for sabotage and espionage in the United States following the success of the first wave. Supported by Canaris, he sent the first teams of agents to America well-equipped to support themselves and their operations for two years. Each team leader – Dasch and Kerling – carried with them a list of contacts, Germans known to be sympathetic to the Nazis. The lists were written in invisible ink on a handkerchief.

The team leaders were to contact Nazi sympathizers known to the Abwehr and Gestapo, establishing and utilizing a network of mail drops and contacts through which additional teams could communicate with one another. Substantial German communities in cities were to be plumbed for support for the German operations. The support of the German communities was considered to be necessary for the long-term maintenance of the teams. The United States was not yet on a full war footing when the teams arrived in America, and security was still relatively lax, which the Abwehr believed would allow their agents to assimilate in the German areas with little difficulty.

6. The sabotage teams had false documents and American money

The teams carried $50,000 dollars, in denominations of $50 or less, under control of the team leader, to be used for expenses including travel, purchases of additional explosives and, if necessary, bribes of officials or supporters. Each man was also allotted $9,000 — about half of which was controlled by the team leader, with the rest carried in money belts by the agents. An additional $400 was held by each member for immediate use. All of the money was genuine to avoid the unnecessary risks inherent with using counterfeit funds.

Kerling’s team was tasked with bombing the Newark station of the Pennsylvania Railroad, repair facilities near Altoona, Pennsylvania, the Hell Gate Bridge, and Ohio River dams and locks between Cincinnati and Louisville. Dasch was to target the electrodynamic plants at Niagara, Alcoa plants in several states, and the cryolite processing plant in Philadelphia. Both teams were to target department stores and large train stations wherever possible, with the aim of creating terror among the populace. The agents all carried false documentation which supported their carefully crafted backstories as they moved freely to accomplish their missions.

5. The New York team was accosted by the Coast Guard, escaped, and a manhunt began

As Dasch and his team buried their explosives on the beach in the dark at about 2:30 in the morning of June 13, he noticed someone on the beach staring at him. It was US Coast Guardsman John Cullen. Dasch told Cullen that he and his party were fishing, though they lacked fishing equipment. When Cullen appeared suspicious, Dasch threatened him, then attempted to bribe him with $260. Cullen promised to forget what he had seen and returned to his station at Amagansett, where he informed his superiors of what he had seen, and more importantly, heard. While Dasch was speaking to him Cullen heard the others talking – in German

By the time the Coast Guard returned to the site the Germans were gone, but they discovered evidence of digging and when they went back to their station it was with the information that explosives and German uniforms were buried on the beach. Before Dasch’s team arrived at Penn Station in New York, the FBI in Washington knew of the discovery on Long Island. Dasch and his team split up in New York, registering in pairs at two hotels, safely hidden in the throngs of the city. In Washington, the information was filed accordingly. Kerling’s team had not yet landed when Dasch arrived in New York.

4. The teams planned to meet in Cincinnati to begin their attacks on the 4th of July, 1942

The following day Dasch told the agent he was traveling with, Ernst Burger, that he had no intention of carrying out the attacks as planned, and was instead going to inform the FBI of the entire operation. Burger was given the choice of either cooperating or being thrown out of their upper story hotel room window. Dasch called the FBI on June 15 and was disregarded as a crackpot. The next day he traveled to Washington, checked in at the Mayflower Hotel, and went to the FBI with his information. After he presented the large sum of American cash he was carrying he got the Bureau’s attention. The fact that his story confirmed the findings on Long Island was also noted. Within a few hours, using his information, the FBI had the rest of his team in custody. Kerling’s team landed in Florida the same day.

Dasch could not give the FBI much information regarding the whereabouts of the second team, only that the teams were to meet in Cincinnati on July 4. He did tell the FBI about the invisible ink on the handkerchief. He could not recall the means of revealing the ink. The FBI allowed Dasch to remain in his Mayflower Hotel room, where he was closely watched, while it rapidly solved the mystery of the invisible ink, which was reactive to ammonia. The listed contacts in several cities were placed under 24-hour surveillance. FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover ordered the arrest of Dasch’s team kept secret, so as not to alert the remaining four German saboteurs.

3. The remaining Germans were rounded up in New York and Chicago

Kerling and his associate, Werner Thiel, traveled from Cincinnati to New York, where Kerling contacted Helmut Leiner, whom he knew from his earlier life in America. Leiner’s name was on the list provided to the FBI and he was under surveillance. The FBI followed Kerling from that point on, and when he met with Thiel in a bar a few days later they promptly arrested the pair, leaving just two of the German agents still free. Though the FBI did not know it, they were in Chicago, where one of them, Herbert Laupt, had also decided to forego his mission.

Laupt had been raised from the age of five in Chicago, and in 1940 failed to register for the draft, as the law then required. Desirous of marrying his girlfriend, he went to the FBI office in Chicago and told them that he had contacted his draft board. The FBI recognized his name and let him go, hoping he would lead them to the sole remaining German agent. After three days of following him, they arrested Laupt for espionage. Laupt, hoping for leniency, told them they could find the last agent of Operation Pastorius, Hermann Neubauer, at the Sheridan Plaza Hotel. He was taken into custody by the FBI that same evening when he returned from watching a movie. As soon as news of the arrests in Chicago reached Washington, Dasch was arrested.

2. The Germans were tried as spies by a military tribunal

Hoover proudly announced the arrests of the team of German saboteurs as the result of an FBI operation, failing to mention the role played by Dasch when he approached the Bureau with the story. He preferred the public and the Germans believe in the efficiency of the American security effort. For the same reason, he urged the Germans be tried by military tribunal, in secret, telling President Roosevelt that a public trial would reveal too much of the FBI’s methods. Roosevelt agreed, and the eight were tried together by a tribunal of seven Army generals, with the Attorney General of the United States, Francis Biddle, serving as the prosecutor.

The Germans were provided with legal representation, but the outcome of the trial was a foregone conclusion. All of the Germans were tried under the penalty of death if found guilty, which they were on July 27. The court recommended the death penalty, though Biddle recommended clemency for Dasch and Burger. The entire court transcript, which ran over 3,000 pages, was sent to Roosevelt, who held the authority to implement the court’s recommendation or grant lesser sentences. Roosevelt’s review of the documents revealed to him that Hoover’s reports of the FBI’s role in the unraveling of the German plan had been somewhat exaggerated. Dasch’s role in exposing the plot remained hidden from the public.

1. All were sentenced to death by the tribunal, but FDR extended clemency

Roosevelt accepted the recommendation from Biddle, supported by Hoover, and granted clemency for Burger, who was sentenced to life at hard labor, and Dasch, who was sentenced to 30 years in prison. His decision was announced on August 7, 1942. The following day the remaining six German agents were executed in the District of Columbia Jail, using the electric chair. They had been back in the United States less than two months. An enraged Hitler forbade Canaris from conducting further sabotage operations in the United States when he learned that all eight of the agents had denounced Nazism to the FBI. Truman later commuted the sentences of Burger and Dasch, ordering them deported to occupied Germany

Neither were welcomed in Germany, where they were generally reviled as traitors. Dasch tried several times over the remainder of his life to return to the United States, but Hoover blocked his efforts each time. Dasch reported that Hoover had offered him immunity from prosecution in exchange for his giving the story to the FBI; Hoover steadfastly denied he had. In 1959 Dasch published a book entitled Eight Spies Against America, which related his side of the story. It did not sell well, nor did it generate support for his quest for a Presidential pardon, as he had hoped. Dasch died in Germany in 1992, still condemned there as a traitor.