American folklore is a vast treasury of stories and tales which have been passed down through time, often altered in the retelling. Some are based in fact, some were created as fiction and are now accepted as fact, and some are simply tall tales. In some cases, political or personal enemies slandered their contemporaries, and their falsehoods are now accepted as history. In others, the public perceptions created beliefs which are largely unchallenged today, despite their being wrong both then and now.

Some stories became accepted as true because of locations taking financial advantage of them, along the lines of “George Washington Slept Here” signs on old inns and homes, despite the lack of supporting provenance. Others lodge in the consciousness through repetition in film and literature. Here are 10 tales of American folklore which have come to be misunderstood as historical fact, and how they became that way.

10. Betsy Ross and the design of the American flag

Betsy Ross was a seamstress in Philadelphia who legend and folklore assigns the credit for the design and creation of the American flag, consisting of a constellation of stars in a blue field, and 13 alternating red and white stripes. Those who support the belief, which has been widely debunked, have recently used the premise that there exists no proof that she didn’t. They are correct. But there is perhaps less to prove that she did. There is substantial evidence to establish that Betsy sewed flags for the Continental Navy (actually for the Navy of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania). But the first documented record of her creating what became the Stars and Stripes did not appear until the 1870s, coincident with America’s centennial, when it was reported by her grandson.

That gentlemen, William Canby, presented a paper around the time of the Centennial claiming Betsy had created the American flag. His sources were entirely family oral tradition. Betsy was presented as an example of patriotism and ambition to young girls of the Gilded Age as a result. However, other than the claims of Canby, and the resultant years of the story being repeated ad nauseum, there is no evidence that Betsy Ross created the American flag, and no record of her ever presenting it to George Washington. There is a record of a team of Philadelphia flag-makers presenting him the Union Flag, which contained a Union Jack in the blue field and which Washington raised above his headquarters in Cambridge, but the same record does not mention Ross by name.

9. Ponce de Leon wasn’t seeking a Fountain of Youth

Juan Ponce de Leon is widely believed to have sought in vain for a mythical Fountain of Youth in Florida, which today has many establishments using the legend to attract tourists. But it is only a legend, one in which Native Americans told the Spaniard that the key to immortality and perpetual youth could be found in Bimini. De Leon first came to the Americas as part of the second expedition of Christopher Columbus and by the early 1500s he was Governor of the Spanish settlements in Puerto Rico, acquiring significant wealth through his Royal appointment. Diego Columbus, brother of Christopher, succeeded in deposing him as governor in 1511, and de Leon decided to explore lesser known areas of the Caribbean.

His legal battles with the Columbus brothers and their allies left him with several political enemies, and it was one of these who first linked de Leon with the Fountain of Youth. De Leon made several voyages to the coast of Florida, and charted it as far south as the Keys, finally attempting to establish a permanent settlement there in 1521, after the death of his patron, King Ferdinand. Wounded in battle with natives resenting the Spanish trespass, he traveled to Cuba, where he died. A biography by Gonzalo Fernandez printed in 1535 was the first to claim de Leon had been in search of the Fountain of Youth (as a cure for impotence); later biographers picked up the unverified tale, and the legend was born. Nothing contemporaneous with the life of the explorer mentions either the search or the mythical fountain.

8. The Pilgrims didn’t land at Plymouth Rock

There were many chroniclers of the voyage of the Mayflower and the landing of the Pilgrims both on Cape Cod and later at what became Plymouth Colony, and still later Massachusetts. None of them mentioned landing on a rock. Indeed, it would have been exceedingly strange for an accomplished seaman to choose a rocky outcropping as a place to land a wooden boat laden with passengers in rough weather. The New England coast in December is seldom placid, and the Pilgrims had already landed on other sites, were concerned about the weather, and were in search of a safer location.

Over a century after the landing Plymouth Rock entered the annals of the colony, when a church elder named Thomas Faunce claimed that his father had told him the rock now known as Plymouth Rock was where the colonists first stepped ashore. The story took hold in the settlers’ collective imaginations. By the time of the Revolution it was a symbol of freedom, and a misguided attempt to move it to a place of honor near a liberty pole resulted in its being broken in two. The bottom half of the rock remained in the ground, the top later suffered another accident and was broken in two again. In 1880 what remained of the top was reunited with the bottom (using cement) and 1620 was carved into its face.

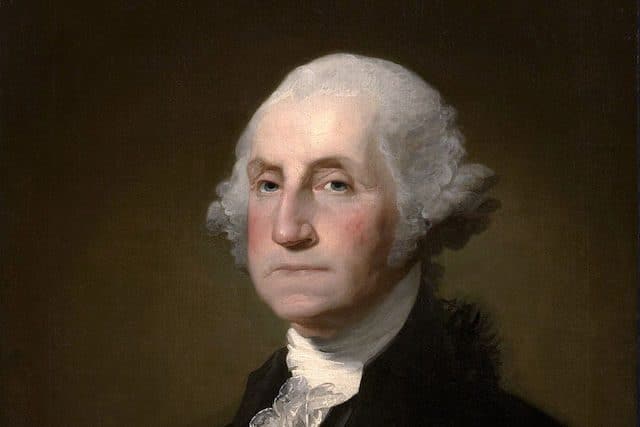

7. George Washington didn’t throw a dollar across the Potomac

Many myths exist about George Washington and a few have at least a passing reflection of basis in truth. Throwing a dollar across the Potomac isn’t one of them. The Potomac at Mount Vernon is almost one mile across. The US did mint two silver dollars of differing design in the 1790s, today known as the Flowing Hair and Draped Bust dollars. In Washington’s day they were scarce, and Spanish dollars (the famed Piece of Eight) were still in wide circulation throughout the new nation. Washington didn’t throw one of those across the Potomac either. The story of the cross-river toss was born out of another story, which featured another river and another item thrown.

According to George Washington Parke Custis, Washington’s step-grandson, the river was the Rappahannock, the site the Washington family home near Alexandria, and the item was a rock about the size of a silver dollar. But Custis heard the story from family lore. Charles Wilson Peale also told a story of Washington’s ability to throw an iron bar a prodigious distance, a popular game among young men before the Revolutionary War to test themselves against one another. Washington was also reported to have thrown a rock to the height of Virginia’s Natural Bridge. So, while he never tossed a dollar across the Potomac, he evidently had a throwing arm of considerable strength.

6. John Henry was not a steel driving man, but a composite of several men

John Henry, according to folklore, was a steel-driver drilling holes in rock to fill with explosives, part of the construction of railroads in the Appalachians. His legend is that he raced against a steam driven machine and won, only to collapse and die of exhaustion at his victory. Several locations in America claim to be the site of the race. The Coosa Mountain tunnel in Alabama is one such site. The Lewis Tunnel in Virginia is another. Yet another is the Greenbrier Tunnel near Talcott, West Virginia. Other sites which have been suggested as that of the legendary race between man and machine are Oak Mountain in Alabama, in Kentucky, and even in Jamaica.

John Henry first appeared in song, sung by the men swinging sledge hammers and handling the rods driven into rock. There were several different versions of the song depending on the area of the country but they all shared a central truth. The hard, physical labor of men with no other job prospects was gradually being eliminated by machines. Many of those workers were former slaves, or the sons of former slaves, and they sang of their woes as they worked, as had been done on the plantations of the south before the Civil War. John Henry was a legend they created out of other men they had known, the hardest worker no longer among them.

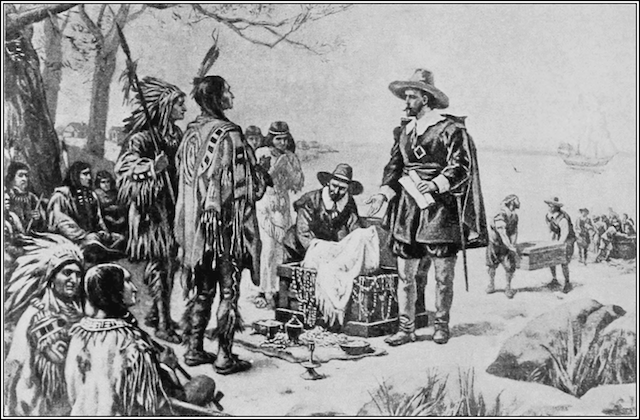

5. Manhattan was not sold to the Dutch by gullible Native Americans for $24 and change

A longstanding bit of American folklore which has acquired the authority of history is that Dutch settlers, led by the crafty Peter Minuit, purchased Manhattan Island from an Indian tribe for a collection of beads and other trinkets, worth about $24. The story at once displays the duplicity of the European settlers and the trusting nature of the Indians, who from that point on were doomed to continuous fleecing by the onrushing settlement of the whites. The truth of the matter is that the tribe with whom the Dutch negotiated, the Manahatta, didn’t own the land which they sold in the first place. Enterprising Dutch settlers had already established a fur trading and lumber camp on the tip of the island, and along streams to the north.

To protect the fledgling settlements from the depredations of roaming tribes, the Dutch approached the Manahatta, offering to purchase the lands they already occupied. The Indians didn’t live or hunt on the lands, and thus had no objection to taking Dutch goods in exchange for what was already a fait accompli. The actual value of the transaction, in today’s money, was several thousand dollars, which seems low until it is considered that the Indians sold the Dutch land for which they had no claim. Basically the Manahatta carried out the equivalent of selling their neighbor’s house and making off with the profits, leaving the Dutch to deal with an unhappy true owner.

4. The legend of Mike Fink may have been based on the adventures of several men

Mike Fink was a real person who in life and after his death took on the legends and tall tales told of other riverboat men, along the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Born in Fort Pitt in 1770, he moved down the Ohio River sometime after the American Revolution and the Indian Wars in the Ohio Country ended. Although he is linked in legend to the Ohio River, there is evidence that he actually operated a freighting business along the Great Miami River of Ohio. There he carried products from the farms of Ohio to Cincinnati, and returned upriver carrying needed merchandise from the wharves of the growing city.

The river towns and frontier settlements were rough and ready places, and stories of Fink, who was well known for his size and prodigious strength, appeared up and down the Ohio, and carried along its many tributaries during his lifetime. Activities of other rivermen and travelers were related in taverns and inns, with his name attached to give them extra flavor. He undoubtedly related more than a few himself. Over time the less admirable facets of his nature made him appear as an undesirable character. When Disney featured him in a film with Davy Crockett during the Crockett craze of the 1950s, Fink was rendered little more than a buffoon. His name is still well-known along both sides of the Ohio, though few could say who he really was.

3. Paul Revere never finished his famous midnight ride to Concord

There were riders from Boston and Charlestown on the Massachusetts roads on the night of April 18 (and into 19), 1775, alerted by the famous signal from Old North Church of two lanterns, warning that the British were coming by sea. The signal was sent by Paul Revere, not to him, before he was carried across the Charles River to mount a horse locally known for its speed. From there, he is known in legend (thanks to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow) for alarming “every Middlesex village and farm.” According to Longfellow it was “two by the village clock” when Revere arrived in Concord. But in truth he never made it to Concord at all. The British captured him outside of Lexington, confiscated his horse, and he walked back to the village.

The Sons of Liberty had a well-established chain of riders and church bells to spread the alarms, which had been exercised previously, and when Revere arrived in towns such as Somerset and Medford, the local militia companies sent out riders of their own. It was the sound of the bells spreading the alarm, as well as some gunshots meant to rouse the militia in Lexington, which encouraged the British patrol that captured Revere to confiscate his mount and return to the relative safety of the approaching British column, rather than confront the aroused village on their own. Revere was just one of many riders along the roads that night, several of whom alerted the village of Concord.

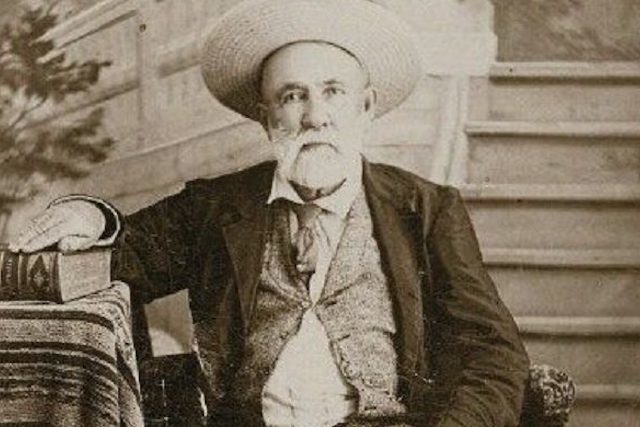

2. The Law West of the Pecos, Judge Roy Bean, was hardly a hanging judge

Judge Roy Bean ran a saloon in Val Verde County, near the Rio Grande River in Texas. He gained appointment as the local Justice of the Peace, and hung a sign on his business establishment which read “Law West of the Pecos.” He did have some acquaintance with the law, having been arrested himself for assault, petty theft, public drunkenness, and threatening to kill his wife. After his appointment as a Justice of the Peace was verified by Texas authorities, he used his new status to run a competitor in the saloon business out of town. He based his judicial decisions on a single law book, once letting a murderer free because he “could find no law against killing a Chinaman” in his reference.

Bean became part of the legend of the Old West, known as a hanging judge, in the sense that all who appeared before him as defendants were likely to be found guilty, and likely to receive the maximum punishment allowed. In truth he only ordered two convicted men to be hanged. He usually fined miscreants the amount of money they had on their person at the time of their appearance, which he kept for himself. As a Justice of the Peace he conducted weddings, announcing “May God have mercy on your souls” following the vows. He also granted divorces, though he had no legal authority to do so.

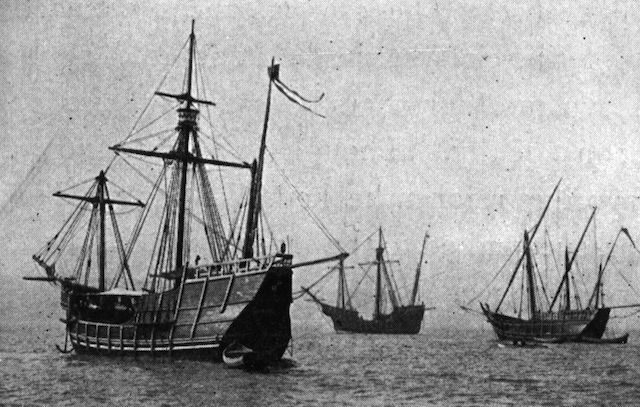

1. Isabella’s jewels didn’t fund the voyage of Columbus, Italian lenders did

Christopher Columbus attempted to obtain funding from several different sources, including the Kings of France and Portugal, before he approached Isabella and Ferdinand with his project. When he did, they at first turned him down. It took nearly two years of persuasion and negotiation for Columbus to obtain the support of the Catholic Monarchs, as they are known today. The longstanding and pervasive myth that Isabella pawned or sold her jewels to fund the voyage is false; the funding came from the royal treasury, which obtained them through loans from numerous sources, including Italian bankers from Genoa and Florence doing business in Seville.

The main source of the loans was the Bank of St. George, based in Genoa, with branches across Europe. The bank was operated by the powerful Genoese Centurione family, rivals of the Medici family. Security for the loans which funded Columbus was speculative, based on the expected riches he would bring back from his voyage. They were serviced, that is the interest on them was paid, through an increase in taxes in Western Spain. Christopher Columbus’s voyages to the New World were paid for in a surprisingly modern way, not by the Queen of Spain pawning her jewelry.