Combat aircraft were born in the fury of World War One, but they truly came of age in World War Two. It was here that domination of the skies became almost as important as control of the land below. Vast fleets of bombers could reduce entire cities to smoldering ruins, and battleships that had taken years to build could be destroyed in a matter of minutes.

For the first time air power could be the difference between victory and defeat, and in this list we take a closer look at the most powerful air forces of World War Two.

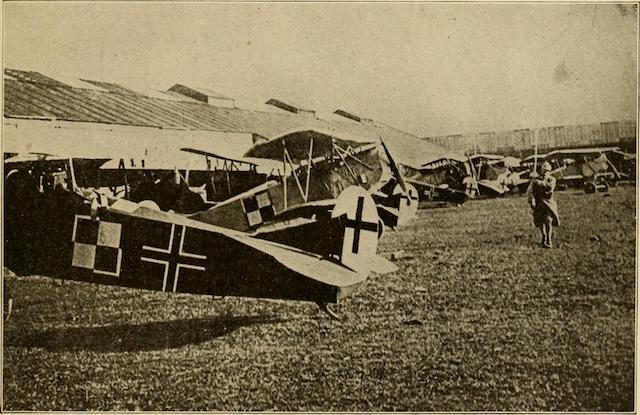

8. The Polish Air Force

On September 1, 1939 Germany invaded Poland in the opening act of World War Two.

The German Luftwaffe planned to catch the Polish Air Force on the ground, destroying it before it could react. German propaganda trumpeted the claim that the Polish Air Force had been wiped out in just three days, and a totally one-sided slaughter has become the generally accepted version of events. However, Polish airmen fought longer, harder, and more effectively than is generally recognized.

While the Germans did destroy large numbers of aircraft on the ground in the first hours of the attack, these were mostly training aircraft. Much of Poland’s fighter force survived.

This still left only 200 or so hopelessly outnumbered Polish fighter aircraft against well over a thousand German Luftwaffe machines. To make matters worse even the best Polish aircraft were hopelessly outclassed. The PZL P.11 wasn’t terrible when it was introduced in 1934, but by 1939 it was already very much obsolete.

The Polish Air Force could at least count on some extremely talented pilots. Despite being heavily outnumbered and lumbered with inferior aircraft, the Poles shot more than 100 Luftwaffe machines from the skies and destroyed hundreds of tanks and armored vehicles on the ground.

With diminishing supplies of aircraft, fuel, and spare parts, the Polish Air Force’s effectiveness quickly tailed off, but its last kills were recorded as late as September 17, 1939. Many of the surviving pilots succeeded in fleeing to Britain to join the RAF, where they would number amongst the bravest and deadliest pilots of the Battle of Britain.

7. Armee de l’air

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8hAsXUVzXlI

France’s air force was once the envy of the world. In 1918 it could launch more than 3,000 frontline combat aircraft into the sky, more than any other nation could muster. France had produced some of the greatest pilots of the war, and French aircraft were amongst the most advanced.

In 1934 the Armee de l’air was established as an independent branch of the military, taking its place as an equal alongside the army and the navy. However, by the outbreak of World War Two, France had squandered her lead in the race to dominate the skies.

As Germany became ever more threatening, the French had put three billion Francs, around 40% of their entire military budget, into the defensive fortifications of the Maginot Line. Substantial amounts were also poured into four hugely expensive new battleships, which would be of little to no use in any future war with their increasingly belligerent German neighbor.

The Armee de l’air received only around a tenth as much funding as the German Luftwaffe in the years leading up to World War Two. It went to war in 1939 with around 250 operational bombers and 800 fighters. The numbers weren’t terrible, but most of these machines were obsolete and unfit for the demands of a modern war.

The Dewoitine D.520 was a notable exception. It was arguably superior to even the best German fighters, but only a handful of squadrons had been equipped with them. When Germany invaded France in May 1940, they were too few in number to make any real impact.

While individual French pilots fought bravely, ground control was almost non-existent, and there was little evidence of anything approaching a coherent overarching strategy. It wasn’t uncommon for pilots to return to their home airfields only to find them already overrun by the Germans.

The Armee de l’air fell with France, but some pilots escaped to fight on with Britain’s Royal Air Force and the Free French forces.

6. Regia Aeronautica

When Italy declared war on France on June 10, 1940 it seemed to be a disaster for the Allies. Italy’s army numbered 2.5 million men, and her powerful fleet would threaten vital shipping routes in the Mediterranean Sea. The Italian air force, the Regia Aeronautica, numbered almost 3,000 aircraft, and the Italians held more world aviation records than any other nation in the world.

It would turn out that much of this strength was illusory. In November 1939 General Giuseppe Valle had conducted a review of the Regia Aeronautica’s capabilities. He found much of the fleet to be obsolete, and a lot of what remained to be non-operational. His report that the famed Regia Aeronautica could only call on 396 somewhat modern bombers and 129 modern fighters promptly earned him the sack.

Mussolini expected to profit from a quick war, and the alarming news concerning the shambolic state of his air force didn’t deter him.

In October 1940 he even somewhat optimistically dispatched an air expeditionary force to aid his German allies in the Battle of Britain. It was the sort of help the Germans could have done without; 24 Italian aircraft were downed without reply, having achieved little other than providing target practice for the pilots of Britain’s Royal Air Force.

5. Imperial Japanese Air Service

In 1925 an American named General William Mitchell submitted a report warning of a possible Japanese attack against the US military base at Pearl Harbor. Nobody paid any attention whatsoever. The idea seemed fantastical then, just as it did 16 years later in 1941.

The Japanese were in fact far stronger, and bolder, than almost anybody anticipated. Aircraft carriers would eclipse battleships, and the Japanese had invested heavily in these weapons of war. Through the skillful use of their carriers Japan had the means to project air power across the Pacific Ocean.

In the excellent Mitsubishi Zero they possessed a long-range carrier-based fighter that was, in 1941 at least, competitive against any other fighter in the world. For striking power, they could call on the Nakajima B5N torpedo bomber, probably the best aircraft of its type in the world.

For a time Japan ran riot, scoring victory after victory, but the first major blow to Japan’s air power came at the Battle of Midway. The 292 aircraft they lost could be replaced. Four carriers and many of their best, most experienced pilots could not.

Japan produced almost 80,000 aircraft between 1939 and 1945. This was a lot, but it was still fewer than any of the main belligerents other than China. To make matters worse they continued to rely almost exclusively on the Mitsubishi Zero, even after it had been eclipsed by the next generation of American aircraft.

A failure to mass produce a successor to the Mitsubishi Zero began to cost Japan particularly dearly from early 1944, when the Americans launched a strategic bombing campaign aimed at Japanese cities. Zeros were unable to climb high enough to engage the raiders, allowing US bombers free reign to roam at will over the home islands.

A lack of fuel, aircraft, and experienced pilots had by October 1944 persuaded the Japanese to pursue a strategy of massed kamikaze attacks. These caused immense destruction but were a sign of Japan’s weakness. Unable to compete through conventional means, this was the only way Japanese air power could attempt to change the course of the war.

4. The Red Air Force

In June 1941 the Red Air Force had a frontline strength of almost 10,000 aircraft. In terms of sheer numbers this made it the most powerful air force in the world, but in terms of operational effectiveness it lagged well behind.

The overwhelming majority of its aircraft were obsolete, and many of the most competent officers had been sacked, imprisoned, or killed during Stalin’s purges. A woeful training program meant that Soviet pilots often had around only 10 hours of solo flight experience to their name.

To make matters worse, Stalin had forbidden the reconnaissance flights that would have revealed the extent of the vast German military build-up along the 1,800 mile Soviet/German border.

The invasion that Stalin had been convinced would never happen finally came on June 22, 1941. The German hammer blow landed with devastating impact. On the first day alone almost 2,000 Soviet aircraft were destroyed. Within weeks of the invasion, the Red Air Force had all but ceased to exist.

Despite the huge losses inflicted upon it, the Red Air Force made a surprisingly rapid recovery. The majority of its aircraft had been destroyed on the ground, leaving most of the pilots to fly another day.

Factories were relocated far to the east, safely out of German reach, where they began churning out aircraft in vast quantities. Unlike the obsolete designs they replaced, some of these were extremely good. The Ilyushin II-2 is regarded by many as the finest ground-attack aircraft of the war. Only five of them survive to this day, but more than 36,000 were built, making it the most produced aircraft of World War Two.

In 1941 inexperienced Soviet pilots had desperately resorted to ramming German aircraft, by the end of the war their leading aces had dozens of kills to their names.

3. The Royal Air Force

In the years after World War One, an Italian military theorist by the name of General Giulio Douhet popularized the theory that future wars would be won through airpower alone. The bomber would always get through, and it would leave nothing but smoldering ruins in its wake. The job of the army would be relegated to simply mopping up shattered survivors and occupying territory.

The prospect of death from above was particularly alarming to the British, who until the advent of the twentieth century had been largely safe from attack in their island home.

While most nations focused on how to best use aircraft in support of their army, the British didn’t have a large army and didn’t expect to field one. The RAF, which became an independent branch of the armed services as long ago as 1918, turned much of its attention towards the defense of British skies.

The result was that by the summer of 1940 the British could call on the most sophisticated ground control system in the world, a chain of radar stations across the coast, and almost as many single-engine fighter aircraft as the Luftwaffe.

This force was put to the test in the Battle of Britain, the first battle in history to have been fought almost exclusively by aircraft. While the number of aircraft involved was comparatively small compared to some of the engagements yet to come, the importance of the Battle of Britain can hardly be overstated.

If the RAF and Fighter Command had lost control of the skies over Southern England, even briefly, then Hitler might have dared to make good on his threat to invade.

Britain’s offensive capabilities did not match up to her defensive ones, at least until the introduction of the Avro Lancaster heavy bomber in February 1942. Heavy losses early in the war forced the RAF to resort to night bombing, which was considerably safer but also far less effective.

Britain’s Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, had seized on the idea of bombing Germany into submission, largely because it was for quite some time the only means Britain had of hitting back.

The bombing campaign gradually took on a life of its own, with the likes of Arthur Harris, chief of the RAF’s Bomber Command, insisting that his bombers alone were a war-winning weapon.

Quite how effective the bombing campaign was is still a matter of debate amongst historians. Despite the vast destruction wrought on Germany, military production continued to rise until well into 1944. However, as Albert Speer, Germany’s armaments minister noted, every gun and aircraft that defended Germany against attack from the air was a weapon lost to the crucial Eastern Front.

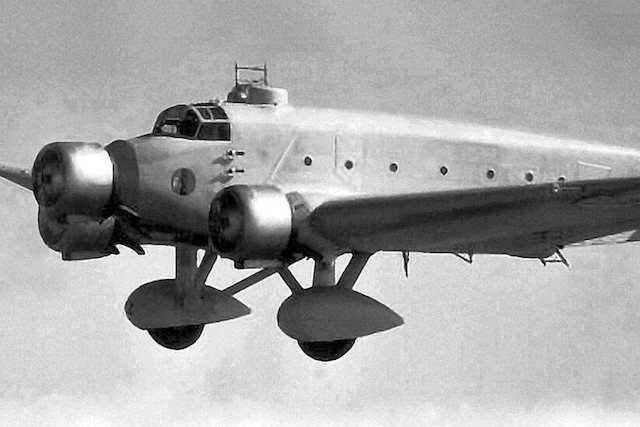

2. The Luftwaffe

At the end of World War One Germany had been banned from maintaining an air force under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles. By 1939 Germany’s Luftwaffe had risen again, widely feared as the most modern, powerful air force in the world.

Early German victories over Poland and France bestowed an aura of invincibility over the Luftwaffe. But as the war dragged on its weaknesses gradually became apparent.

The Luftwaffe lacked a modern torpedo-bomber, had no strategic bombers, and its much-feared JU-87 Stuka dive-bomber was already effectively obsolete by the outbreak of war.

Like all Nazi institutions, the air force was a vipers’ nest of infighting and personal power struggles. Presiding over it all was Hermann Goering, a once-daring combat pilot who by 1939 had become a lazy, sycophantic drug addict.

The Luftwaffe had been designed as an offensive weapon that would operate in close support of the German Army. While German aircraft dominated the skies, the German Army won its great victories of 1939-1942. As German aircraft became an ever-rarer sight, German victories became far scarcer.

In the wake of the Battle of Stalingrad, which was almost as much of a disaster for the Luftwaffe as it was for the German Army, the Luftwaffe was stretched far too thin on the vital Eastern Front. Meanwhile, the Allied bombing campaign forced huge numbers of aircraft to be redeployed in a brutal battle of attrition to protect German skies.

The Luftwaffe’s revolutionary jet fighters might have been a war winning weapon, but they arrived too late to change the course of the conflict. In 1939 Germany had boasted the world’s most powerful air force, but it was ground down in a war of attrition, before finally being crippled entirely through a lack of fuel.

1. The United States Army Air Force

American military planners went to war in December 1941 with several assumptions about the capabilities of their aircraft.

They believed their fighters were competitive, that their heavy bombers were quite capable of defending themselves without a fighter escort in broad daylight, and that the Norden bombsight would allow their aircraft to land a bomb in a pickle barrel from 20,000 feet.

This optimism quite quickly proved to be misplaced. American frontline fighter aircraft were markedly inferior to the Japanese Mitsubishi Zero, to the extent that pilots dubbed their Brewster Buffalos as “flying coffins.” Even the heavily armed Flying Fortress bombers were badly mauled whenever they ventured out alone over occupied Europe.

The Americans were forced to largely abandon long-ranging forays into Nazi Germany, settling for softer targets that lay within the limited range of escorting fighters.

The US already had a solution to their fighter escort problem, they just didn’t know it yet. P-51 Mustangs had first flown in 1940, but they were regarded as a mediocre, somewhat underpowered aircraft. This changed in October 1942 when a British engineer suggested fitting them out with the Rolls Royce engines that powered Britain’s Supermarine Spitfires.

With this simple change the P-51s were transformed into one of the greatest fighters of the war. They were that rarest of beasts: a long-range fighter capable of outperforming short-range interceptors. With the addition of an extra fuel tank they could carry out operations deep into the heart of the Reich. When Goering first learned that P-51s had been sighted over Germany, he flew into a rage and dismissed it as an outrageous lie.

P-51s served almost exclusively in Europe, but other superb aircraft such as the Vought F4U Corsair and the Grumman F6F Hellcat changed the balance of power in the Pacific theatre of war.

The Americans didn’t just have quality, they also had quantity. Between 1942 and 1945 American factories produced around 275,000 aircraft. This was more than Germany, Japan, and Great Britain combined.