Roman history is typically overshadowed by the lives of its famous generals and notorious emperors. However, the rank and file legionnaires, particularly those of the later Republic and Principate, are widely revered as some of the greatest soldiers ever to engage in warfare.

In many ways, military service hasn’t changed much through the ages: harsh discipline, lousy food, cramped living quarters, and the ever-present danger of being wounded or killed in battle. Soldiers in ancient Rome took on the added weight of providing the lifeblood of a nation by constantly expanding and defending its borders while facing rebellion on all fronts.

Relying heavily on its martial prowess, Rome would transform from a kingdom to a republic and finally into an empire. But it came with a hefty price at the expense of the common soldier.

8. Class Warfare

Most young men born poor or into a family of low standing in Roman society faced few (if any) prospects. Joining the army provided at least some upward mobility in the highly divided class system headed by the patricians, the wealthy and ruling strata; underneath them, the plebeians constituted most of the citizenry as well as the bulk of its fighting forces. Though “plebs” could own land and had voting rights, the majority lived in over-crowded urban squalor.

Lastly, freedman, slaves, and outsiders from the provinces (non-citizens) made up nearly half of Rome’s population during the first century AD (about 500,000 people). They often took up refuge in the city’s Catacombs, a labyrinth of damp underground tunnels and caves riddled with vermin — and an ideal breeding ground for plagues. Although slaves weren’t permitted to serve in the military, freedmen (former slaves released from servitude) could join the legions but only in an auxiliary capacity with less pay and often greater danger.

On the surface, it would seem that only those lucky enough to land in the aristocratic upper echelon might escape a hard life and violent death. Hardly. The murderous scheming and subversive actions of Rome’s elite would help cure generations of writer’s block as well as spawn the Hollywood epic “sword-and-sandals” film genre.

7. Call To Arms

The thrill of adventure, bloodlust, and even glamour have always served as an allure for young men to go to war. But like many like before and after them, legionnaires would often leave home never to return, representing little more than pawns waiting to be sacrificed and left rotting on a foreign field.

Roman recruits typically enlisted as a volunteer at the ripe age of 17 or 18 but could also be conscripted to maintain troop levels or provide urgent needs. During the reign of Augustus, men were required to serve 25 years and forbidden to marry — a restriction designed to keep them focused on the task at hand.

Fighting men typically earned limited financial compensation, but a veteran would be eligible for a lump sum pension and a piece of land in special designated colonies from previous campaigns. However, due to a relatively short life expectancy and compounded by the likelihood of being killed or dying from disease, true reward came in the form of honor earned in battle or booty from vanquished lands.

6. Survival of the Fittest

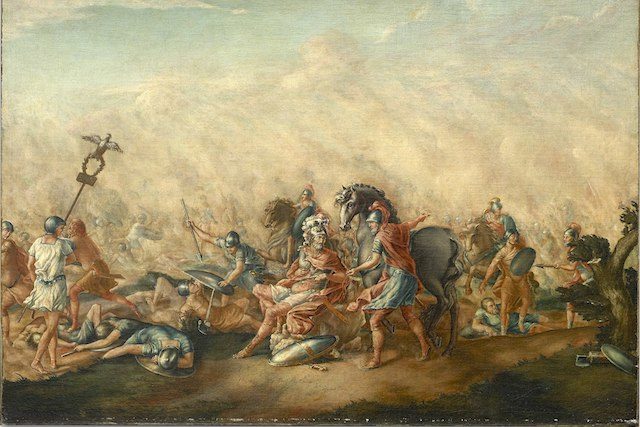

The Romans relied heavily on organizational structure and a deep supply of well-trained troops. The ability to fight as a disciplined, cohesive force created an appreciable advantage over many of its fierce but independent-minded combatants such as Germanic and Celtic tribes.

Roman legions, the main operating units of heavy infantry, were divided and subdivided into tactical units of cohorts, centuries and contuberniums — and rigorously prepared for combat with a comprehensive regimen that would create the basis for modern-day boot camp.

Under the landmark reforms by Marius Gaius at the end of the 1st century BC, a wider section of the population was allowed to serve. Standing armies had previously consisted of only land-owning city dwellers but now included citizens from newly acquired regions. Soldiers also became more mobile and self-sufficient, carrying all of their gear on their backs, earning the nickname, “Marius’ Mules.”

Men were expected to march 30,000 paces a day (about 20 miles) while carrying up to 80 pounds. Typical equipment included body armor (lorica segmentata), sword (gladius), shield (scutum), and two javelins ( pilum (spears) along with a backpack (scarina), containing food rations and other useful tools. In addition to building strength and endurance, troops drilled relentlessly in weaponry and tactical maneuvers such as the hollow square, wedge, and tortoise formations.

After arriving at their destination dead tired and hungry, soldiers then set up camp. Each man was responsible for preparing and cooking his meals, which usually consisted of barley and wheat — as well as anything foraged or taken by force.

5. “Cedo Alteram”

The necessity of strict order is a cornerstone of any well-functioning army. Not surprisingly, the Romans embraced several heavy-handed methods when it came to keeping troops in line. Their rigid code of discipline was typically enforced by a Centurion, a tougher-than-leather drill instructor who makes Gunnery Sergeant Hartman in the film Full Metal Jacket appear warm and fuzzy.

After enrolling in the military, a legionnaire swore an oath known as the sacramentum, pledging that he’d obey and fulfill his conditions of service inclusive of death. The centurion’s stick (vitis) came to symbolize the harsh treatment carried out regularly in the same way Roger Federer hits stinging backhand winners.

Tacitus mentions a particular centurion named Lucilius, who earned the nickname “Cedo Alteram” (“give me another”) because he repeatedly broke his stick from constant abuse. Furthermore, Pliny added: “The centurion’s vine staff is an excellent medicine for sluggish troops who don’t want to advance…”

4. Border Wars

Although estimates vary, the Roman Empire numbered between 65 million and 100 million people at its peak around 117 AD. Borders stretched from North Africa in the south to Britannia in the north and covered large swaths of Continental Europe. Patrolling this vast expanse not only required an enormous army to maintain order but also warding off attacks from a long scroll of enemies.

To be fair, western civilization would greatly benefit from the innumerable Roman contributions and inventions such as calendars, newspapers, arches, aqueducts, sewers, and the construction of over 250,000 miles of roads. Despite these advancements, many conquered people refused to capitulate and instead made it their mission in life to resist until their last dying breath.

Space restrictions prevent naming all of Rome’s major rivals, but the legendary Carthaginian general, Hannibal Barca, warrants special attention. According to legend, his fate as a celebrated warrior began when his father took him to the temple of Baal, making the nine-year-old boy swear to be an eternal foe of Rome in a series of conflicts known as the Punic Wars.

Hannibal would cement his reputation as one of the greatest tacticians in military history by emerging triumphant at the Battle of Cannae in 216 BC. Featuring a strategy that actually included war elephants, over 50,000 Roman soldiers were killed or captured by a much smaller force (possibly as few as 10,000) in a bloodbath that historians have characterized as the perfect ‘battle of annihilation.’

3. No Rest For The Wicked

Overworked and underpaid — the bane of all working stiffs. The same can be said for most legionnaires, who in addition to relentlessly training, marching, and fighting provided the labor required to build an Empire. Literally.

The demands of war saw the legions maintain a heavy workload year-round. When not soldiering, they spent a considerable amount of time and manpower erecting Roman forts and defensive bases by employing the same disciplined approach used to destroy foreign armies. Additionally, the State augmented a soldier’s already busy schedule with a bevy of non-military functions.

Ranging from agriculture to mining, well-organized Roman muscle became multi-purpose instruments capable of chopping, grinding, slicing and dicing to ensure all sectors ran smoothly. Author Simon Elliot writes: “…before the advent of a civil service, nationalized industries and a free market able to find major capital expenditure projects, to fulfill these responsibilities it turned to the only tool at its disposal namely the military, the largest institution within the empire.”

2. The Great Unknown

The snap of a twig. A slight vibration underfoot. Foreboding dark clouds on the horizon. It’s been said that fear of the unknown can be as terrifying as any mortal threat experienced in combat. And even the most hardened Legionnaire would have his nerves regularly tested by encountering more lethal scenarios than the cringe-worthy TV series, A Thousand Ways to Die.

For anyone serving in the legions, the possibility of dying in battle would have been expected. While geography played a key determining factor in one’s adversary, the same is true for a wide of range of lurking dangers such as drunk war elephants, poisonous snakes and severe weather that ranged from blistering hot deserts to freezing tundra.

More than likely, getting trampled to death by a three-ton beast probably isn’t the most peaceful way to check out. Neither is painful suffering from the plague. In 165 AD, the Antonine Plague, one of the worst pandemics to ever hit mankind, claiming the lives of as many as 5,000 Romans per day. Modern historians believe the disease (a form of smallpox or possibly measles) might have been carried by troops returning from the near East.

1. Death Squads

In an episode about the origins of Christianity on PBS’s Frontline, Professor Allen D. Callahan states: “The Romans had a genius for brutality. They were good at building bridges and they were good at killing people, and they were better at it than anybody in the Mediterranean basin had ever seen before.” While this double-edged compliment certainly rings true, it fails to mention one crucial detail that made it all possible: the Roman soldier.

Among the barbarous torture devices used in the ancient world, the Romans are best known for their use of crucifixion as a sanctioned form of punishment. After all, it’s how they killed Jesus. And several accounts of the Spartacus-led slave rebellion in 71 AD describe slaves being nailed to crosses along a 100-mile stretch of the Appian Way, where they remained “until their bones were picked clean by vultures.”

Just how painful was crucifixion? The word “excruciating” derives from this act and reserved only for slaves and outlaws — especially those refusing to worship Roman gods. The targeted persecution of Christians is particularly well-documented — and would later result in biblical authors writing The Book of Revelation. Tacitus wrote that early followers of the faith, “were nailed on crosses…sewn up in the skins of wild beasts, and exposed to the fury of dogs; others again, smeared over with combustible materials, were used as torches to illuminate the night.”

There’s a scene in the film A Clockwork Orange in which Alex (Malcolm McDowell) daydreams about being a legionnaire mercilessly whipping a bloodied and beaten Christ. What makes the sequence so powerful (and disturbing) is that the enforcer truly enjoys his job. One may argue this portrayal of sadistic cruelty is merely the interpretation of a historical event by a visionary auteur (Stanley Kubrick again) pushing the boundaries of cinematic scope.

Or not.

Lessons from the past clearly illustrate no shortage of horrendous deeds, including but not limited to: the Inquisition, Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade, Native American genocide, Andersonville, the Rape of Nanking, the Holocaust, My Lai Massacre, and the Killing Fields of Cambodia.