Known as Micajah (Big Harpe) and Wiley (Little Harpe), the pair of thieves, rapists, kidnappers, and murderers were likely not brothers at all, though legend records them as such. Hailing from the western mountains of North Carolina, they were likely cousins who fled to the region of the Ohio Valley after their Loyalist leanings during the American Revolutionary War (and their crimes in the Yadkin Valley) made them fugitives. They were among the first Americans to become the subjects of organized searches by armed groups of vigilantes, eluding them by fleeing from one territory to the next, a trail of victims in their wake. Kentucky, what is now West Virginia, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and Tennessee were all sites of their criminal activities, and at least three dozen murders have been attributed to the pair. There were likely many more.

Their story is one of the dangers of the opening of the west in the days following the end of the Revolutionary War. It is permeated with river pirates, highwaymen, murders blamed on Indians, fur trappers and hunters vanishing forever in the unexplored American west. They may have been Scottish emigrants. They may have been brothers born to North Carolina settlers. They may have been legally married to women they identified as their wives, or they may have presented the victims of kidnappings as their spouses as they traveled the Ohio and its tributaries. Or they may have done both. Separating the myth from the reality is difficult, though the brothers were described by many along the American frontier; criminals, legal authorities, and community leaders all left behind tales of their crimes and travels. Here are tales of the Harpe brothers, verified through the extant records, though in some cases the records themselves are of a questionable nature.

10. They fought on both sides of the American Revolutionary War

The earliest traces of the Harpe brothers come from today’s Orange County, in western North Carolina, in the decade preceding the American Revolutionary War. Whether brothers or cousins, the pair were of Scottish descent, and their activities (and those of their fathers) would have included serving either in the interests of the King or those of their neighbors during the Regulator War, an action by settlers indifferent to English authority, represented in the Carolinas by officials viewed as thoroughly corrupt. Likely born under the name Harper, Micajah was the elder and physically larger of the two. The younger was Wiley, also known as Joshua. Both used the turmoil of the Revolution and the divided loyalties of the frontier settlements as excuses for criminal activities following the outbreak of open warfare against England and its Loyalist supporters.

Having developed the local reputation of being Loyalists in the earlier opposition to Great Britain’s authority, the Harpes joined Tory gangs which were little more than terrorists in the 1770s. Their activities included the murder of settlers suspected of being allied with the Patriots or those who were neutral, stealing their supplies, burning their farmsteads, and kidnaping their women and children, in the belief that British authorities or Indians allied to the British would pay a ransom. Rape was used as a weapon of terror by such gangs, and existing written testimony includes the Harpes on such raids. In 1780, Patriot militia reported the Harpes as being present at the Battle of King’s Mountain, after which they reportedly joined a band of Chickamauga Indians (a tribe of the Cherokee nation). At least one – Micajah – was present at the Battle of Blue Licks in Kentucky in 1782, when Virginia and Kentucky militia led by Daniel Boone and other frontiersman were defeated by British allied Indians and militia. Boone’s son Israel was among the Patriot dead.

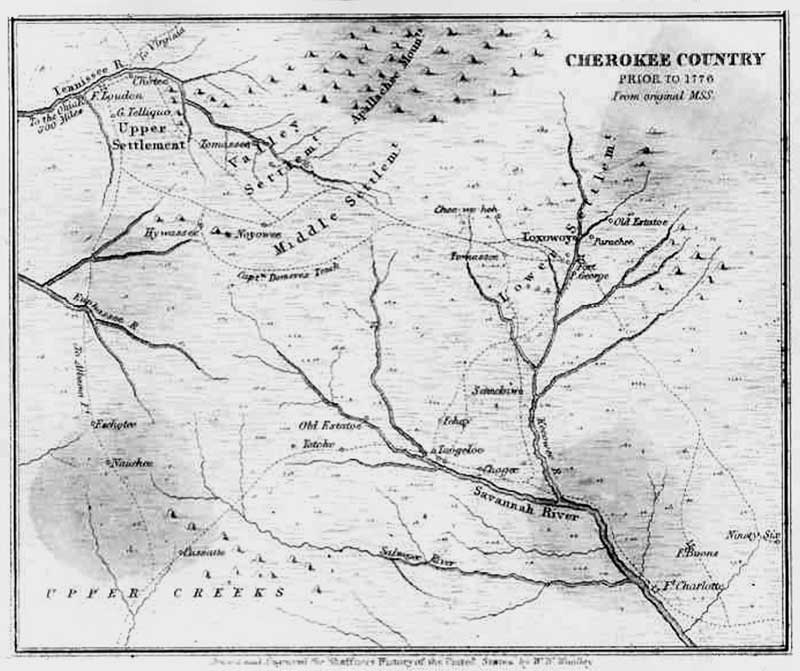

9. The Harpes lived with the Chickamauga near present day Chattanooga for at least a decade

Following the end of the American Revolution Micajah and Wiley Harpe, enemies of former Loyalists and Patriots alike, lived in the Indian village of Nickajack, near what became Chattanooga, Tennessee. Though little is known of their activities during their time with the Indians, the decade following the American Revolution saw the opening of Kentucky and Tennessee to settlement, as well as the outpouring of new settlers into the western lands via the highway provided by the Ohio River and its tributary streams. Conflicts between hunting parties – Indian and white – as well as raids on homes of both parties were common. By the early 1790s militia formed by the new settlements were planning and conducting substantial raids of retribution against what they considered to be hostile Indian settlements. One such raid was conducted by Kentucky militia against the village of Nickajack in 1794.

The raid against Nickajack was conducted, in part, as a reprisal for the kidnapping of women from the white settlements, including two women – Susan Wood (known to the Harpes as the wife of a militia officer) and Maria Davidson. By the time militia raided Nickajack, both women and their captor’s – the Harpes – were gone. It was around that time the pair shortened their name from Harper, and in 1795 they were known to be living near Knoxville. They developed the local reputation of petty thieves and ne-er do wells, residing in a cabin on Beaver’s Creek, from which they resisted any attempts to chastise them. Official law not yet being present along the frontier, they enjoyed an immunity enforced by their own guns and reputations, though Knoxville records indicate that Wiley Harpe entered the courthouse to marry a local woman, Sarah Rice, in June of 1797.

8. 1797 saw the beginning of a crime spree which rivaled that of Bonnie and Clyde a century and a half later

Shortly after Wiley Harpe took himself a wife the Harpes began a crime spree which spread across the American frontier, committing known murders in what became Kentucky, Tennessee, and Illinois, and probably an unknown number of killings along both banks of the Ohio River. Eventually they confessed to 39 murders of men, women, and children, at a time when the murder of Indians for the most part did not count. The killing spree – which included kidnapping and multiple rapes as well – began after the town of Knoxville grew tired of the Harpe’s thievery and ran them out of town for the crime of stealing a pig, which on the frontier was a serious theft. They were also suspected of stealing horses, also a serious crime, and shortly after their departure from the environs of Knoxville a horse owner who had accused them was found having been butchered and his remains weighted down with stones and submerged in a creek.

The brothers fled the mountains of eastern Tennessee and headed north to Kentucky, where the Wilderness Road pioneered by Daniel Boone and the Ohio River provided a steady stream of potential victims, most of whom traveled laden with all of their material possessions. Authorities in the raw Kentucky settlements soon responded by dispatching parties of volunteers to seize the brothers (or better yet, kill them) but their efforts were thwarted, and in more than one instance, the leader of a group in pursuit of the pair was found dead, usually with his body savagely cut and torn into pieces. By 1799 the Governor of Kentucky placed a reward on their head, promising $300 to anyone who brought them, or their recognizable corpse or portions thereof, to the authorities. The brothers fled to the north to continue their spree.

7. The Harpes joined a band of river pirates on the Illinois side of the Ohio River

Criminals being pursued by Kentucky authorities had merely to cross to the north of the Ohio River to be secure from their interference. The Ohio was then a dangerous place, with both sides of the river offering hidden lairs for pirates who preyed upon the settlers moving downstream. Often disguised as Indians, the river pirates struck the flatboats and canoes moving along the river and practiced the long-held belief of their Caribbean and deep-ocean colleagues that dead men tell no tales. Trappers and long-hunters moving upstream with furs to sell at Wheeling and Pittsburgh encountered the same remorseless gangs. One of the most feared along the entire Ohio Valley was the Mason Gang, which made its home at Cave-in-Rock in the Illinois Territory, north of the Ohio. It was there that Big Harpe and Little Harpe sought refuge, and joined with Mason and his followers, taking with them women they identified as their wives.

The Mason Gang was known for its utter disregard for human life, with tales of its cruelty discussed not only along the frontier, but in the eastern cities including Philadelphia and even Boston. Yet the Harpe’s exhibited a new level of barbarism, at which even the hardened river pirates were appalled. The brothers took captured women, survivors of their attacks on the riverboats, and used them for a time, after which they needed to kill them in accordance with the practices of the Mason Gang. Wiley Harpe took to killing his victims by forcing them, often on horse or muleback, to ride off the top of a bluff to drop to the Ohio below, killing both (horses and mules, being branded, were evidence of a crime if found in the wrong hands). By the end of the summer of 1799, the Mason Gang had seen enough of the Harpes, and ordered them to leave their haven of Cave-in-Rock, unable to stomach further their indifference to their own bestial behavior.

6. Micajah Harpe killed an infant believed to have been his own daughter after leaving Cave-in-Rock

In the summer of 1799 the Harpes were forced to leave the Illinois pirate stronghold by the pirates themselves, choosing to return to the Kentucky side of the Ohio River, taking with them – at Mason’s insistence – their “wives” and children. The brothers were intent on returning to their hunting grounds of eastern Tennessee, and the Kentucky woodlands which bordered them, avoiding larger settlements with their inconvenience of militia units and constables reporting to the governor. It was near Russellville, Kentucky, that summer of 1799 that Micajah Harpe committed one of his most heinous murders in a career of many. Upset with the continuous and annoying crying of his daughter, Harpe killed the child by smashing her brains out against a tree, in full view of its mother. Micajah Harpe later confessed to the murder, the only such crime for which he expressed any regret.

By that time there was a growing string of murders, including the butchering of an entire family, found by the Harpes as they slept along the trail, en route to a better life in the new land of the west. The Harpe’s killed with knives, guns, tomahawks, and even large rocks, and among the traveling settlers they victimized killed the slaves found with them. In late August, 1799, they stayed at the farmstead of Moses Steagall in Webster County, Kentucky. While there Micajah killed another guest staying the night, after which he killed Steagall’s four month old son by cutting his throat, yet again driven to murder by the crying of a child. The child’s mother lived long enough to see her son murdered before she too became a victim, after which Micajah sat down to eat the meal she had prepared for her guests. Her husband, Moses Steagall, was not home at the time of the killings, but would soon be aware of what had happened to his family.

5. Micajah was the first of the pair to be brought to justice

By the end of August, 1799, Kentucky had had quite enough of the Harpe brothers, and a posse which included Moses Steagall among its number caught up with the pair in Webster County. Wiley, living up to his name, eluded the pursuit and escaped, but Micajah was wounded in the leg by a rifle shot and captured. During the questioning which followed, Big Harpe confessed to having committed murder along the frontier. In fact, he confessed to twenty murders of his own, leading his captors to infer several others were committed by his brother. During his confession he expressed his remorse for having brutally beaten his daughter’s brains out. Whether or not Micajah succumbed to his wound before Moses Steagall cut off his head is unknown (some said not), but Harpe’s head was placed on a spike as a warning to others, at a spot marked with an historical marker today, along what became Harpe’s Head Road.

Micajah Harpe left behind several women who were identified at different times and places, and by different witnesses, as being his wives. Some may have been the wives of Wiley Harpe as well, traded between the brothers as they continued their spree. Several were the survivors of earlier crimes, and they were held for a time and released by the authorities, after which they returned to their previous lives, more or less. Among them were Maria Richardson and Susan Wood, both of whom lived in Russellville, Kentucky while awaiting a new life to develop around them. Women, at least women unburdened with a husband, were still relatively rare on the frontier, and both later remarried and lived “respectable” lives in the regions where they had traveled, if not as part of at least as witnesses to one of the worst killing sprees in history.

4. Wiley Harpe continued his criminal career undeterred by the death of Micajah

With Micajah dead, Wiley Harpe elected to leave the jurisdiction under the Governor of Kentucky, and rather than travel south to Tennessee he re-crossed the Ohio and next showed-up at Cave-in-Rock. From the fact that he was welcomed back to the fold of the river pirates which had only that same summer evicted him, one can infer that he was the less violent of the two Harpes, and thus acceptable to the pirates. The killer known as Little Harpe also had with him his wife, whom he had legally married in North Carolina before the killing spree began, the former Sally (or Salley) Rice. For the next several years Little Harpe lived and worked with the Mason Gang of river pirates, though some of the gang at least and certainly Wiley Harpe also branched into other areas of thievery, including as highwaymen along the increasingly trafficked thoroughfare of the Natchez Trace.

In the late summer of 1799, shortly after the return of Wiley Harpe to Cave-in-Rock, a group of Kentucky settlers who called themselves the “Exterminators” decided that the niceties of the law and issues of jurisdiction were irrelevant. Their attack on Cave-in-Rock led Mason to relocate, moving his criminal operations to the Mississippi, where he was protected from American interference by Spanish authorities, many of whom could be made tractable through bribery. Thus shielded, raids could still be made on American settlers as long as the raiders’ made it back safely to Spanish territory. As the 19th century began Mason and his cronies were safely ensconced in Spanish Louisiana, which then included most of what is now Missouri and Mississippi. Mason was so certain of his security he began signing his crimes along the Natchez Trace, leaving his own name at the crime scene as “Mason of the woods,” written in the blood of the victims.

3. The Natchez Trace was one of the most dangerous routes in North America

Long before President Thomas Jefferson directed the completion of a postal road connecting Daniel Boone’s Wilderness Road to the Mississippi, the route which became known as the Natchez Trace was an Indian highway through the wilderness. In 1801 Jefferson directed the United States Army to improve the road, work which was accomplished slowly, and it remained a remote and dangerous route, with stops for the most part consisting of inns known as stands. These were, as often as not, operated by individuals working with the hundreds of highwaymen which operated along the road, most frequently in its most isolated areas, deep in the difficult woods and forests. Among the highwaymen was Wiley Harpe, working with the notorious Mason.

In April 1802, Wiley Harpe was reported to be in the company of Samuel Mason in the Mississippi Territory near present-day Yazoo. From 1799 until 1804, during which time the United States acquired the Louisiana Territory by purchasing it from Napoleon (who had never legally acquired it from Spain, though that is another story), Little Harpe continued his depredations along the Trace, engaging in theft and murder, and working with another Mason Gang member in the art of forgery, often passing forged Spanish currency and coin, as well as other documents. Gradually the improvements wrought by the Army on the Trace, the influx of new settlers, and the push northward from New Orleans, all combined to close a noose upon the Mason Gang, and in 1803 Spanish authorities captured Samuel Mason and most of his gang, including Wiley Harpe. While being transported to New Orleans, Harpe and Mason escaped, Harpe using the alias John Sutton.

2. Wiley Harpe tried to sell out Samuel Mason following their escape from the Spanish

While being held by the Spanish, Harpe learned that Mason (who when captured had in his possession over $7,000 in Spanish currency and the scalps of more than 20 victims) was worth a substantial bond to the Americans. Both Harpe and Mason were using aliases, and the Spanish, unaware who they really were, were in the process of turning them over to the American authorities for suspected crimes committed in American territory when they escaped. Mason, however, was wounded in the head during the escape. Harpe concluded, quite reasonably it would seem, that Mason was going to die anyway, and since he was of value to the Americans, Harpe should turn him over under his real name, collect the bounty, and vanish into the American woods along the Natchez Trace. He enlisted a confederate from among the gang to deliver Mason to the Americans, this time as Mason, rather than under an alias.

Mason disrupted the plan by dying prematurely from his wound, and Wiley and his confederate, James May, attempted to placate the Americans by delivering the dead river pirate’s head and thus receive the reward. Harpe was recognized by the Americans, arrested, and tried in federal court for multiple accounts of murder and other crimes. An attempt was made to charge Harpe with murdering Mason during their escape from the Spanish, but it went nowhere due to lack of evidence, and there was already enough evidence to hang Harpe several times over. Along with James May, who was using the alias Peter Alston, Harpe was convicted and sentenced to death by hanging. He was executed in Old Greenville in 1804. After his execution his head was removed and sent to be displayed on a pike on the Natchez Trace.

1. The Harpes faded from popular memory following the death of Wiley Harpe in 1804

For a time, the Harpe Brothers and their horrendous murder spree remained a subject of lore along the American frontier, though other stories gradually displaced them. In 1809, Meriwether Lewis died under extremely mysterious circumstances at a stand on the Natchez Trace, just a short distance from where Wiley Harpe’s skull remained on grisly display. Daniel Webster found both Harpe brothers on the hostile jury he encountered in the short story The Devil and Daniel Webster, though not in the original version written by Stephen Vincent Benet and published in 1836. They had to wait until the 1941 film version to make their appearance. They also appeared as relatively harmless, almost oafish clowns in Disney’s Davy Crockett and the River Pirates. They were likewise slightly less sinister and defeated rather easily (by Jimmy Stewart and allies) in the 1962 epic How The West Was Won.

In truth, they were neither oafish nor easily defeated, and the trail of murders is no less horrifying despite the passage of time since they were committed. The frontier which they terrorized was a dangerous place to be sure, but neither does that lessen the depravity of their lives of robbery, rape, and murder. Some scholars and historians claim that they may have killed as many as fifty people, some more, and the likelihood is strong that it was many more, given that many people vanished into the deep woods or challenging waters of America’s western frontier, never to be seen again. The Harpe Brothers are the lead characters in one of America’s oldest true horror stories, and the tales of their depravity rival any of the most vicious characters of fact or fiction in the annals of any nation.