We may find it difficult to believe that Agatha Christie, a Victorian wife and mother who wrote crime stories set in rural England, supported feminism through her writings.

Indeed, we will find many critics like Johann Hari who tell us that Christie did exactly the opposite, incorporating “a hostility to feminism” into her stories. The writer is perhaps better known for her partiality towards young and dashing archaeologists and for the most successful disappearing act since Houdini. The latter earned her the title of ‘original Gone Girl‘ in the English media.

But in her own way, Dame Christie was as firm a believer in equal rights for women as the staunchest bra burner.

10. She was a well-paid writer at a time when any woman attempting to claw her way out of the kitchen was diagnosed hysterical

Christie was born in late Victorian England, an era marked by Queen Victoria’s belief that women had to be “what God intended, a helpmate for man, but with totally different duties and vocations“. The best employment most women could aspire to involved serving tea to the remaining aristocracy . Those who escaped the indignity of domestic service to work in factories could expect the same working conditions as those in the worst sweat shops today.

Christie, instead, became a published writer and amassed an undisclosed fortune. Although the writer’s heirs have always refused to disclose the exact worth of her estate, there is the widespread belief that “by some standards Dame Agatha was a millionaire.” Not bad going, considering most of her female contemporaries could only hope for £500 a year and a spot of sexual harassment as housemaid to the lord of the manor.

9. She was one of the first to introduce the idea of the strong female detective in fiction

Up till the 19th century, there was a very clear formula for female characters in novels. This had more to do with snagging eligible bachelors than polishing mental prowess, as seen in books like Jane Austen’s Pride & Prejudice .

Women in detective stories didn’t fare much better. From the detectives in Wilkie Collins’s The Moonstone to Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes, they invariably featured the “duo archetype of two white middle-class males.” Women were merely ornamental to the story.

Enter Christie’s unlikely Miss Marple, who solves some 37 murders through the simple expedient of using logic and drinking tea; Victoria Jones, the antithesis of the Bond Girl in They Came to Baghdad; Bridget Conway in Murder is Easy; and a whole list of other women who acted much like your average man upon being faced with murder; i.e., rashly and with a disregard for possible consequences.

8. Her heroines beat the men to it

Christie’s women win, even when it’s not their job to do so. In Murder is Easy, it is the amateur Bridget Conway who cracks the mystery and not retired police officer Luke Fitzwilliam. In N or M, Tuppence beats her husband Tommy to the scene of a spy investigation, causing the British Intelligence’s head to bestow that ultimate praise, calling her “a smart woman.” In The Man in the Brown Suit, it is Anne Beddingfield who gets all the action and the final victory, not the distinguished Colonel Race. And in 4.50 from Paddington, Lucy Eyelsbarrow – a professional housekeeper – pulls all the strings and manipulates the events that lead to the discovery of the killer, while Detective Dermot Craddock is busy buttering his scones. Christie’s leading ladies manage to defy the gender constraints of the time, “repeatedly subverting patriarchy” to steal the spotlight away from their male counterparts.

7. Her murderers are both male and female

The patriarchal society of the time accepted nothing but the most ideal of female character traits, even in fictional women. Writers created females who were devoted wives, caring mothers and all-round snoozefests. When Ellen Wood introduced the idea of a female killer in her 1860 novel Danesbury House, the plot came complete with a strong moral message about the dangers of women indulging in alcohol. Women did not kill for gain and even less did they kill for the fun of it, because the ingredients that make up a ruthless murderer were just not considered to be part of their genetic make-up. Instead, writers made sure to turn their female protagonists into ministering angels.

Christie broke the mold by allowing women to add murder to their CV. Many of her books have female killers who are just as calculating and strong as the male villains and, just like the latter they are perfectly willing to be corrupted for money, love or other gain.

6. Her stories depict married couples as equals

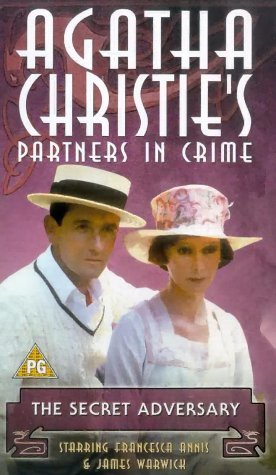

In Christie’s day, well-to-do married women behaved like today’s WAGs. Christie pooh-poohs these life choices through a series of female characters who refuse to conform to the patriarchal structure of marriage. In stories like A Pot of Tea and The Affair of the Pink Pearl, Tommy and Tuppence Beresford are a husband-and-wife sleuthing team; they operate like a power couple minus the expensive divorce attorneys. Prof Gillian Gill describes them as “a team of equals, not as boss and female sidekick”, adding that in many ways Christie’s female characters were the ideal role models for young women of the time and that they “may also have reflected aspects of the author herself”.

5. The success of her female leads is based on brains, not looks

Christie’s murders are solved using the Sherlock Holmes method of deduction. The writer prided herself on creating mysteries that could be solved not by happenstance or guesswork, but by employing logic.

Although Miss Marple was fond of humbly claiming that she only managed to solve the murder thanks to female intuition, the denouement that would invariably follow at the end of every novel pointed at everything else but that. In classic who-dunnit tradition, Christie’s stories always close off with the detective giving a blow-by-blow explanation of the facts that led to the murderer’s cover being blown. Miss Marple’s simple reasoning succeeds in making us feel like complete chumps with every logical deduction revealed, making us wonder why on earth we didn’t manage to reach the same conclusion ourselves – particularly as we are always given access to the same information as Miss Marple herself.

4. Her alter ego is a feminist

One of Christie’s female detectives is Ariadne Oliver, a novelist-turned-detective whom Christie admits is very close to her in character. The list of common personality traits between the two women is substantial. Both created non-English detectives that they then grew to hate – Ariadne found her Finnish detective Sven Hjerson ridiculous, while Christie “wanted to exorcise herself” of Poirot and, in fact, wound up killing him off in Curtain. Both women were shy novelists who never quite knew what to say in public and both had an inexplicable fondness for apples, leading many critics to conclude that Oliver is an exaggerated version of Christie herself.

Oliver is also a straight-shooting feminist, spouting lines like “if only a woman were the head of Scotland Yard and “Men are so slow. I’ll soon tell you who did it,” both from Mrs McGinty’s Dead.

3. Her influence extended to real life crimes

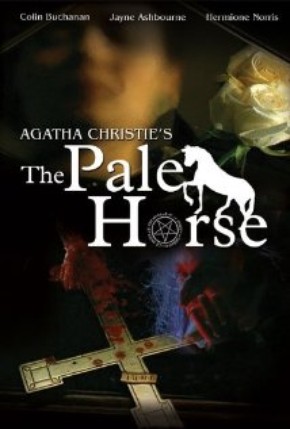

Christie’s impact was not limited to a few local book clubs. Iraq’s first serial killer sourced her inspiration directly from the writer. And the novel The Pale Horse is quoted by FBI profiler John Douglas as having influenced convicted murderer George Trepal to use the poison thallium to dispose of his victim in a case that happened back in 1998.

When Florida resident Peggy Carr succumbed to a mysterious, four month-long sickness, everyone blamed some obscure stomach bug. But medical professionals soon turned a suspicious eye towards Peggy’s next door neighbor, Trepal, a known Agatha Christie enthusiast who regularly organized murder mystery parties.

A police search on his property yielded a copy of The Pale Horse, in which a series of victims are killed by means of thallium poisoning. Peggy’s symptoms did, in fact, coincide with those of thallium poisoning, despite the fact that the toxin had been banned in the US since 1965. A months-long sting operation finally confirmed Trepal’s guilt.

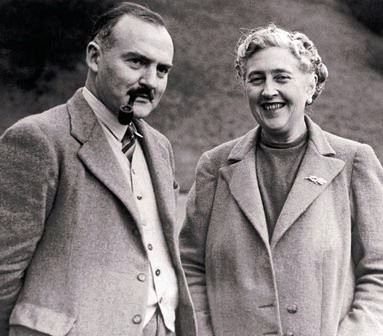

2. When Christie’s first husband left her for another woman, she bagged a man 14 years her junior

Divorce for your average Edwardian woman meant a lifetime of poverty and pity. Not for Christie. Upon being dumped, she immediately landed her errant ex, Archibald, in hot water by disappearing without a trace for 11 days.

When that spot of revenge was out of the way (Christie chose to call it out-of-body amnesia), the writer packed up her bags and went off gallivanting to the other end of the world. This was an unheard-of move for a single mother in the early 20th century. In true yummy mummy style, she then married the much younger Max Mallowan.

But even before her first marriage was shipwrecked, Christie never quite embraced the staid lifestyle expected of married women. In 1922, she parked her toddler Rosalind with her mother for 10 months while she toured the world – a move that certainly didn’t help the writer win any mother of the year awards.

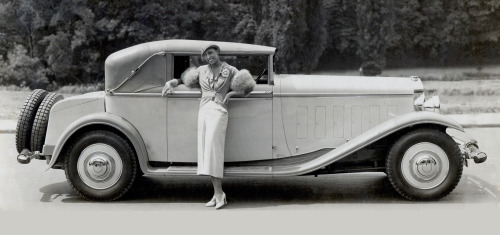

1. Her women drive

During Christie’s lifetime, gallivanting behind the wheel with no chaperon was viewed more as a lucky privilege rather than a right. For starters, the majority could not afford to buy a car. The advent of World War I, however, soon put a stop to gender restrictions and women were, at least temporarily, allowed to take their place behind the wheel. Once they got a taste for it, British women immediately recognized the ability to drive as the gateway to independence that it was and feminist groups worked hard to stop the skill from becoming a man’s sole domain once again after the war.

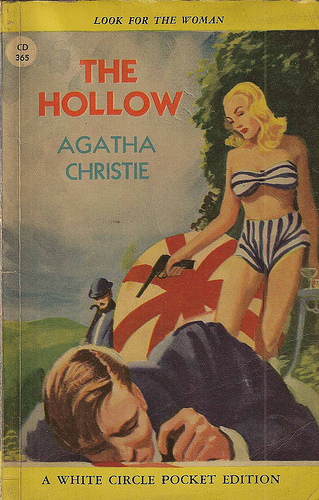

In keeping with the other modern characteristics Christie gives her female characters, not only do many of them drive but they are also exceptionally good at it. They unabashedly show off their “skill in traffic,” like Henrietta Savernake in The Hollow and their “skill… nerve… and reckless pace,” like Bundle in The Seven Dials Mystery.