Native American tribes were plentiful and varied, with different cultures and ways of life. Some were more sedentary and with a focus on agriculture, while others were more nomadic, hunting bison and pronghorn antelope on the vast expanses of the Great Plains. But even though they are often seen as noble savages, driven back from their lands and pushed to the brink of existence by the expansionist Europeans, many Native American tribes were as savage and as warmongering as they were made out to be. And none of them were more powerful, fierce and resilient than the Comanche.

Don’t get us wrong, though. Most tribal societies from all around the world were like this, or close to it. The difference here was that the more technologically advanced Europeans came into contact with them at a far later date than when the Celts or the Huns reigned supreme.

10. A Short Backstory of the Comanche

Belonging to the Uto-Aztecan language family, the Comanche were once part of the larger Shoshone Native American tribe which originated from the western Great Basin. Around 1500 AD, some of them emerged from the Rocky Mountains and onto the Great Plains, in what are now Idaho and Wyoming. Coming into contact and conflict with other tribes like the Blackfoot, Crow, Lakota, and Cheyenne, they started moving further south, some as far as central Texas. These Eastern Shoshone turned into the Comanche by the late 17th century. But up until this point there wasn’t anything special or out of the ordinary about this particular tribe of Native Americans.

They were the typical, small hunter-gatherer tribe of people, with basic culture, almost no social organization, and weak military power as shown by their constant migration up until that point. Contrary to the barren mountain valleys from which they came, the Great Plains offered them a chance to hunt the many bison and antelopes found in abundance. But they also had to compete with the already existing tribes for these resources. However, what else they discovered on these plains would change their destiny forever. Left behind by the Spanish settlers to the south, the Comanche came across the horse around 1680, and with it they engraved their name into the history books as legendary mounted warriors.

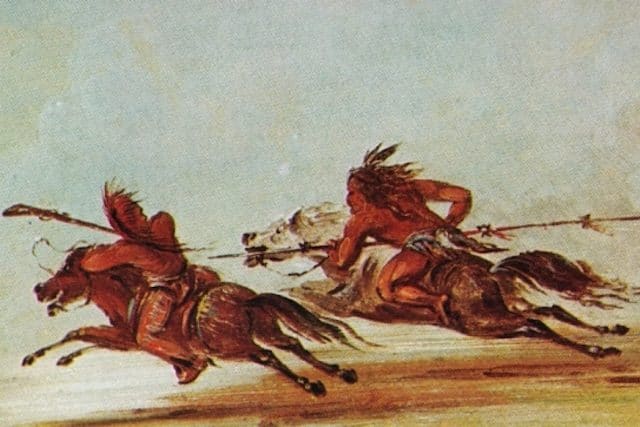

9. Lords of the Southern Plains

Very few nations in the world, let alone in North America, have had such a meteoric rise to power like the Comanche. And this was possible all because of the horse. No other tribe or nation in North America would surpass them in horsemanship, with many experts even going as far as saying that they were the best light cavalry the world had ever seen. The Comanche bred, trained, and captured Mustang horses from both the wild and from other people. With them they became expert hunters of bison and suddenly prospered like never before. In less than one hundred years, from the 1680s to about 1750, they would go on and take much of the southern Great Plains, showing that the horse was exactly what was missing. The horse was to them what electricity and steam power was to the rest of the world.

The Comanche were shorter in stature than the other Indian tribesmen, but bulkier and with a firm grip, making them a sort of perfect jockey. Their Mustangs were the same: small, fast, and tough. And with their newfound mobility and speed, they were able to drive back many of the other Native American tribes in the region and expand their hunting territories. They even nearly drove the Apaches, who previously inhabited the area, into extinction. Their infamy quickly grew among the other tribes, as it’s shown in their name. While they called themselves Numunuu, meaning “the People,” the term Comanche means something completely different. It’s a Spanish corruption of the Ute word “Kohmahts,” which translates to “those who are against us,” or simply “the enemy.”

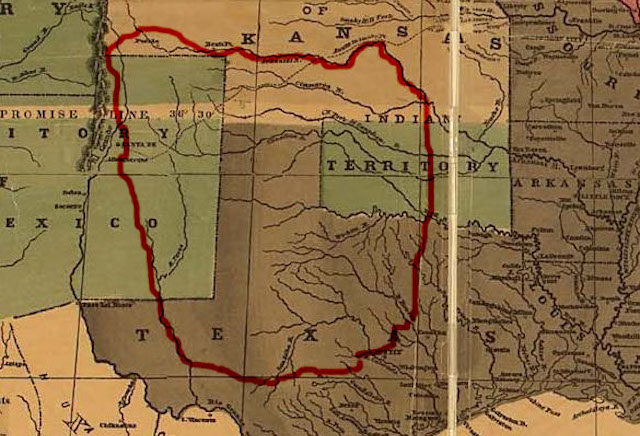

8. The Empire of Comancheria

It’s somewhat strange to talk about an empire when it comes to Native North Americans, especially during the 18th and 19th centuries, but Rhodes Professor of American History Pekka Hämäläinen, among others, calls what the Comanche had just that: an empire. Being a strong influence in the region, the Comanche held control of territories of what are now central and northern Texas, eastern New Mexico, western Oklahoma and Kansas, and parts of Colorado – called Comancheria. They never did organize themselves into a single cohesive tribe, but lived in a loose confederation of about a dozen or more bands. They all shared the same language and culture and rarely fought each other. These bands had names like Root Eaters, Loud Talkers, Eat Everything, Buffalo Eaters, Timber People, Antelope Eaters, Steep Climbers, Honey Eaters, Bad Campers, or Hospitable Ones among others, each hinting at their general location or habits.

They still followed a nomadic lifestyle, living in tepees, moving around, with no interest in agriculture. By the start of the 1800s they made up a population of around 30,000 people. They were a warlike people, either hunting or raiding neighboring tribes and European settlements for supplies, horses, and people for use as slaves. As skilled mounted warriors, they had a horse population of about 90,000 to 120,000 head, and another 2 million wild Mustangs living in or around Comancheria. The Comanche bands even traded in towns along the Rio Grande Valley, sometimes just after a raid in the region. They would bring the people they had kidnapped in order to ransom them back to their families. But while the Mexican, Spanish, and Pueblo Indians were somewhat tolerant of these practices, the Comanche would have a lot of problems in later years with the Americans for the exact same reason.

Nevertheless, by the 1820s they encompassed an area of about 250,000 square miles within their borders. They would go on and vassalize some 20 other smaller tribes and make their language lingua franca for the entire region. They would also halt any European expansion into the area dead in its tracks; the Spanish coming from the south, the French advance from Louisiana, as well as the seemingly unstoppable American colonial expansion from the east. They are the main reason for why the West Coast was settled 40 years before the Great Plains. At times, especially in the 1860s, the American frontier was even pushed back as settlements or even entire counties were deserted in the face of various Comanche offensives.

7. Comanche Society

The Comanche were warriors first and everything else second. When they weren’t hunting, they were raiding their neighbors. Their numbers were bolstered by an increased food supply with the arrival of the horse, as well as the other migrating Shoshone bands from the north. And, of course, the many slaves kidnapped from neighboring tribes and settlers; mostly young girls and women. Their society never had a single leader, and all band chiefs acted as a counsel of advisors for the entire nation. All band leaders could state their opinion, but usually the older ones did most of the talking. There was also the Peace Chief to each band, who was usually the oldest, and chosen by general consensus. The rest would listen to his counsel and expertise on where to hunt, or relocate, who to attack, or with what other tribes they should form an alliance.

During times of war, each band would select a War Chief. For this position, only the bravest of warriors were chosen, and only those who had the respect of the entire band. Either while on a raid or during a prolonged conflict, the whole band would listen to the War Chief, regardless of their status. But once the conflict was over, the War Chief’s authority would end. The children were the Comanche’s most prized possessions, followed only by their horses. Everything else was often times shared or offered between the members of the band.

A young boy would become a warrior at about the age of 15, and only after he hunted his first buffalo. Older men who became more interested in the past than the future would abandon the warrior path and gather in a special tepee called the “Smoke Lodge.” No younger men or women were ever allowed inside. When they felt death approaching, they would give away all of their belongings, find a quiet place, and wait to die. After their death, they would be ceremoniously buried, and the entire band would then relocate. The women handled most of everyday life, including foraging as well as assembling and disassembling the camp, while the men were in charge of hunting and waging war.

6. The Comanche Moon

There’s a reason why the full moon is still called “Comanche Moon” in Texas. The Comanche were notorious for their many raids, especially during a full moon, when under the cover of darkness, but still with enough visibility to get around, the mounted warriors would engage in ruthless and quick raids on the surrounding populations. These raids had the purpose of taking horses, weapons, supplies, cattle, women, and slaves. But while most of these raids were done on the other Indian tribes, the Comanche also performed them on the European settlers on more than one occasion. During these blitzkrieg-like raids, the Comanche, oftentimes numbering no more than a few dozen, would storm in, kill all the men above the age of 10, and even the infants under the age of 3, take whatever and whoever they wanted, and then leave.

By 1720, the Comanche came in contact with the French and through various trading agreements, they were introduced to firearms. In exchange for these weapons, they offered horses stolen in New Mexico. Throughout the 18th century, they were in almost constant conflict with either the Spanish or Mexicans, or with all the many other tribes surrounding their borders, like the Lakota, Cheyenne, Pawnee, Kansa, and Osage tribes. Since 1779, the Comanche also began crossing the Rio Grande and making incursions well within Mexican territory. Some of these expeditions went so far south that the returning raiders reported seeing “little men in the trees who would not speak to us” … which were actually monkeys. These raids were so feared that the government of Nuevo Leon in Mexico forbade people to travel in groups of less than 30 armed and mounted men. From 1840 on, Comanche raids intensified and lasted up until the 1870s. Josiah Gregg, an American explorer, naturalist and author, while traveling through the region, said: “the whole country from New Mexico to the borders of Durango [Mexico] is almost entirely depopulated. The haciendas and ranchos have been mostly abandoned, and the people chiefly confined to the towns and cities.”

5. Torture

The Wild West wasn’t named as such only because very few Europeans lived there, or because the ones who did were lawless gunslingers. The term “wild” here more closely resembled “savage” than “untamed.” Everybody living in the region knew what a Comanche raid meant and what it brought with it. Besides those who were killed in the attack, most women were raped, then murdered, and some were even taken as captives. Scalping was commonplace on the battlefield as a means to mock the enemy, who was still alive but who had his tongue ripped out to silence the screaming. But surprisingly enough, the Comanche women were oftentimes the ones in charge of torturing their captives. And the grisly ways in which they went about it can, at least, be called “imaginative.” Some Spanish sources mention an instance when a group of Tonkawa tribesmen were being tortured by the Comanche by having their arms and legs burnt to the bone. Then the limbs were amputated, only for the practice to start anew on the fresh wounds.

Some other favorite methods included having the fingers ripped or cut off, stuffed into the victim’s mouth, and then sewing his lips together. Then the poor soul was tied naked in a spread-eagle position over a fire ant mound until he died. Others were sewed within a raw animal hide and left in the sun. As the hide slowly shrank, it squeezed the man inside to death. Another favored torture method was to have the victim buried neck deep into a pit and then have his eyelids cut off. With no protection from the sun, the victim’s eyes would sear in the scorching sun, blinding him before he died of thirst or other causes.

4. The Council House Fight and the Great Raid of 1840

The Council House Fight was a failed peace negotiation between the Comanche and the Republic of Texas, which took place in San Antonio on March 19, 1840. The negotiations were aimed at putting an end to two years of fighting, with the Comanche wanting to obtain recognition of their borders, and the Texans wanting the release of 18 prisoners held captive. The Comanche delegation was comprised of 12 Chieftains, accompanied by 53 others, some of which were women and children. But since they only brought with them two prisoners, the Texans decided to hold the chieftains hostage until the safe return of the rest. Hearing of this, the Comanche tried to escape and a battle ensued. In the aftermath, 35 of the Indians, including the Chieftains, were killed, while the rest were taken prisoner. After this betrayal, the Comanche had 13 of the remaining 16 white prisoners gruesomely tortured and killed.

Chief Buffalo Hump of the Penateka (Honey-Eaters) band sent word to the other Comanche and amassed a huge raiding party of at least 400 to 600 warriors. The first town to be attacked was Victoria, Texas on August 6, 1840. They killed several white settlers and black slaves around the town, but the citizens’ defensive efforts made the Comanche leave Victoria more or less intact. Nevertheless, they made off with at least 1,500 horses. Two days later, they came upon the port town of Linnville. This time around, things turned out differently.

Unlike towns and cities in central Texas, coastal ones were unprepared for a Comanche raid. Initially believed to be Mexican horse traders, the Comanche soon surrounded the small port and began pillaging. Some people were killed, but most managed to survive by fleeing to open waters and staying on the small boats. For the rest of the day, the attackers sacked the town, stealing goods worth to about $300,000 (some $8.5 million in today’s money). They also killed the cattle there and made off with an additional 3,000 horses and some prisoners. The Great Raid was the largest such Indian incursion on white cities in the United States, ever. In total, some 33 settlers were killed, and the port town of Linnville never truly recovered. Today it is just a ghost town, as most of the displaced residents then established Port Lavaca, about four miles to the southwest.

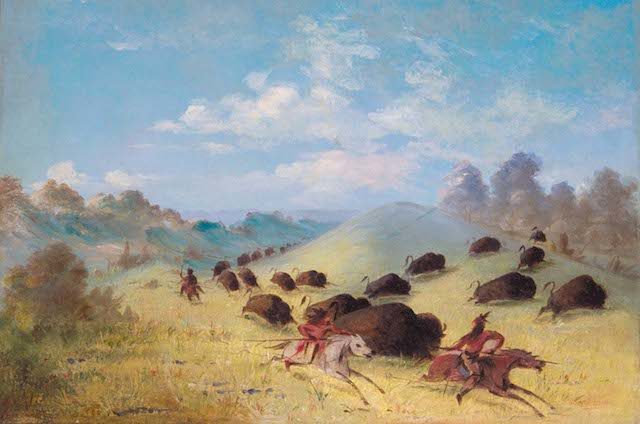

3. The Buffalo

Because of their nomadic lifestyle, the Comanche made use of only lightweight and highly resistant materials. They didn’t use pottery or baskets, and they didn’t forge metals, utilize weaved materials, or carve wood. They relied on the buffalo for most of their material needs and everything from the animal was used in one way or another. In fact, there were over 200 uses for the buffalo. Tools, weapons, and household items all came from the buffalo. The stomach lining, for example, was stretched over four sticks, filled with water, and used as a cooking pot. Dried buffalo dung was used as fire fuel, and its hide, horns, and bones were used for almost everything else they needed. The rest they got through trade. With over 60 million such mighty beasts inhabiting North America at any given time, with most living in the Great Plains, Comancheria became the greatest hunting empire ever.

All of this would change, however, since by the 1880s only about 100 buffalo remained. In the 1830s, the Comanche and other Plains Indians were hunting the buffalo at a rate of about 280,000 head per year. This hunting was for both sustenance and trade, and represented the limit of sustainability the buffalo population could provide in the region. Nevertheless, in the winter of 1872-73 alone, some more than 1.5 million bison hides were put on trains and shipped to the East Coast. Their hides were used for coats and the leather for machinery belts and army boots, among other things. Hunters would receive $3.50 ($110 today) per hide, and were killing buffalo by the hundreds every day. And since the animals didn’t run away if they didn’t see where the threat was coming from, the hunters would pick a vantage point farther away, and slaughtered an entire herd in a mere hours. They would then skin the animals, take the hides, and leave their bodies to rot. The bones were later collected and turned into fertilizer.

Trains passing by would slow down when they came across a herd as to allow its passengers to shoot the buffalo for sport. The US Army actively endorsed this slaughter, and so did the federal government. To be fair, though, the Native American population also had a hand to play here. Nevertheless, in the aftermath that followed, the Comanche and other tribes found themselves without their primary food source, and they were forced to relocate into reservations or starve to death. What’s more, the disappearance of the buffalo from the Great Plains and the introduction of cattle and industrialized agriculture resulted in about a third of topsoil erosion and the ensuing Dust Bowl of the 1930s.

2. Manifest Destiny

With the buffalo becoming scarce, the Comanche had little choice but to focus on raiding. So, by the 1860s Comanche raids intensified, mostly because it was now a matter of survival. Also, numerous smallpox and cholera outbreaks throughout the 19th century severely reduced their population from 30,000 to only about 5,000. By 1867 some Comanche bands and other Indian tribes accepted being relocated to reservations on the condition that the US government would stop killing the buffalo. But since this didn’t materialize, they too had to restart the raiding. In 1871 the famed General William T. Sherman and Lieutenant General Philip Sheridan instituted a scorched earth policy on the remaining Comanche resistance. This meant that everything the US Army came in contact with, from horses to villages and supplies, were killed or destroyed. Their usual trade routes were also disrupted.

The famed chief Quanah Parker and a Comanche medicine man, Isa-tai, gathered some 300 warriors and attacked a well-armed group of buffalo hunters in 1874. Isa-tai promised the Comanche their return to power and a potion that would make them invulnerable to bullets. That obviously didn’t happen, and the attack failed. With a serious blow to morale, the remaining Comanche and their few remaining Indian allies retreated in the canyons of the Texas Panhandle. In what became known as the Red River War, the US Army, with 1,400 soldiers, encircled the Indians and slowly starved them to death. Some 20 engagements took place before, half starved, Quanah Parker and his men surrendered at Fort Sill in June 1875. This marked the end of the Comanche and the other Plains Indian tribes as lords of the Southern Plains and the complete expansion of the US from coast to coast.

1. Quanah Parker – The Last Chief of the Comanche

Born in 1845 to Comanche chief Peta Nocona and Cynthia Ann Parker, Quanah Parker was the last chief to the Kwhandi band. His mother was captured by the Comanche when she was 9 years old and had since embraced the Comanche way of life. She was one of the few white settlers who refused to return to her people. Quanah Parker became chief himself at a relatively young age, and would lead the last resistance of the Plains Indians against the US Army and the Texas Rangers. And even though his attempts at a continued Comanche way of life failed, he was the one who led his people on “the white man’s road” in the years that followed, thus becoming the first sole chief of the whole Comanche nation.

As a skilled diplomat, Quanah represented Comanche interests to the US government and was a familiar figure in Congress, traveling many times to Washington DC. Here he befriended many public figures, including Theodore Roosevelt, who personally invited the Comanche chief to his presidential inauguration in 1905. Quanah Parker also became a successful farmer, businessman and stockholder in the Quanah, Acme, and Pacific Railway. He was also directly interested in settling his people and to consolidate their position, by being given an education and learning agriculture. He was loved by both Indians and whites alike, and at his funeral in 1911, some 1,500 formed a procession more than 2 miles long.

1 Comment

I question your fact. When did we fight the Sioux?