In the early years of the 20th century, the world was being transformed by new technologies, and methods of waging war were no exception. Weapons such as poison gas, machine guns, and tanks were unleashed on the battlefield, and submarines changed the nature of warfare at sea.

Between 1914 and 1918, German U-boats prowled the Atlantic Ocean and the seas around Great Britain in search of Allied merchant ships. It was a high-stakes game of cat and mouse in which the hunter could become the hunted, with the outcome of the entire war hanging in the balance.

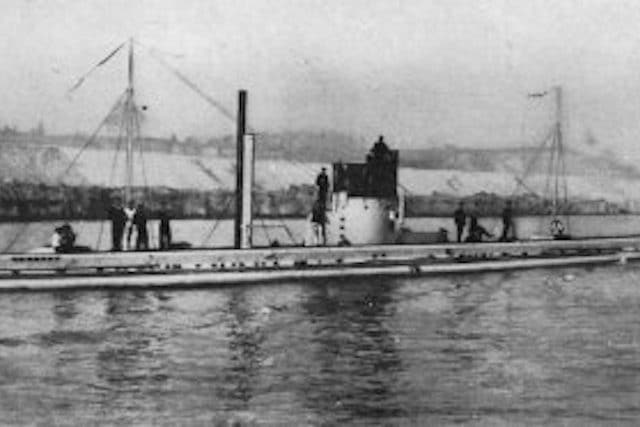

10. Nobody Expected Much of Submarines

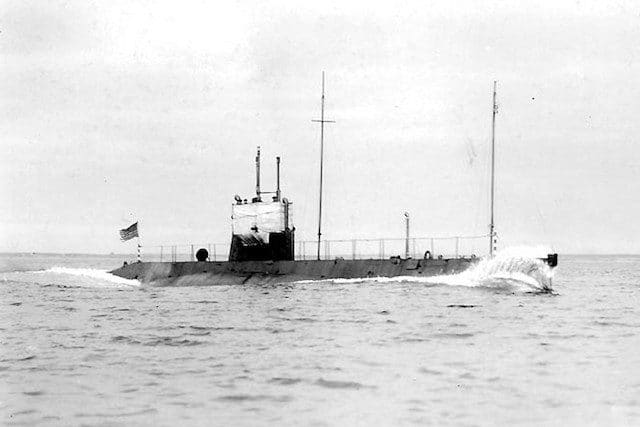

When World War One broke out in 1914, submarines were untested as a serious weapon of war. The only instance of a submarine destroying another vessel had been during the American Civil War. Even that was a qualified success, since the submarine concerned was also sunk during the engagement, most likely from the blast of its own torpedoes.

The world’s major navies could all call on the services of a small number of submarines, but they were very much regarded as a novelty rather than the potentially war-winning weapon they would soon prove to be.

Submarines, or U-boats as the German versions were known, were relatively cheap and easy to build, but the Imperial German Fleet had only 29 of them at the outbreak of hostilities. It didn’t take long for the unconventional weapons to prove their worth.

When three British armored cruisers were lost to the torpedoes of a single U-boat in just one hour on September 22, 1914, Germany almost immediately ramped up production.

9. Prize Rules

Submarines posed a threat to even the largest and most powerful of warships, but the Germans soon realized that hunting warships was not the best use of a U-boat’s time. They were at their most effective when deployed against merchant shipping. As an island nation that relied heavily on imports, the British were particularly vulnerable to this form of warfare. If German U-boats could destroy enough of the food and vital war materials being brought into Britain by sea, the British would have no choice but to sue for peace.

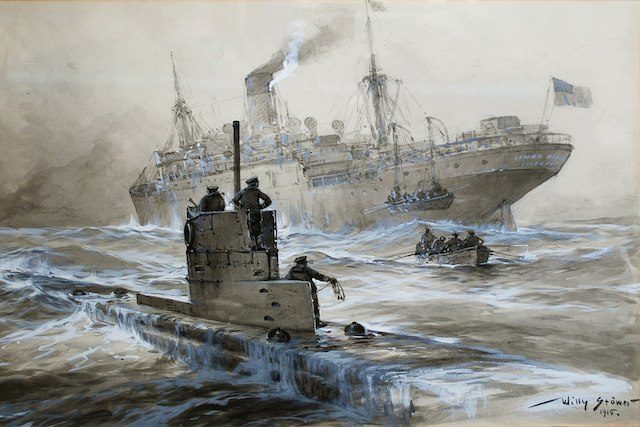

As deadly as the U-boats were, they began the war laboring under a serious handicap. In 1909, Germany had signed up to an international treaty governing the conduct of naval warfare. Under these so-called Prize Rules, submarines were not permitted to attack unarmed merchant ships without first surfacing, giving notice of their intention, and granting sufficient time for the crew to abandon ship.

By giving away their position submarines lost their advantage of surprise, and placed themselves at risk of being attacked by nearby warships or even being rammed by the very merchant ships they were hunting.

In February 1915 the gloves came off. Germany announced that from this point on, any ship in the waters around Great Britain could be attacked without warning.

Unrestricted submarine warfare ratcheted up the pressure on Britain’s supply lines, but Germany’s international reputation plummeted. People around the world were appalled that a supposedly civilized nation would attack innocent civilians and neutral shipping. The Germans had to balance the undoubted effectiveness of this strategy against the danger of provoking the Americans into joining the war against them.

8. Dazzle Camouflage and Q-Ships

The early U-boats were primitive, underpowered, and only capable of diving for short periods of times. However, once submerged they were almost impossible to locate and impervious to attack.

Since almost nobody had expected submarines to play a major role in any future conflict, very little thought had been put into how best to counter them and minimize losses. That quickly changed as the British scrambled for solutions in what had become an unexpected battle for survival at sea.

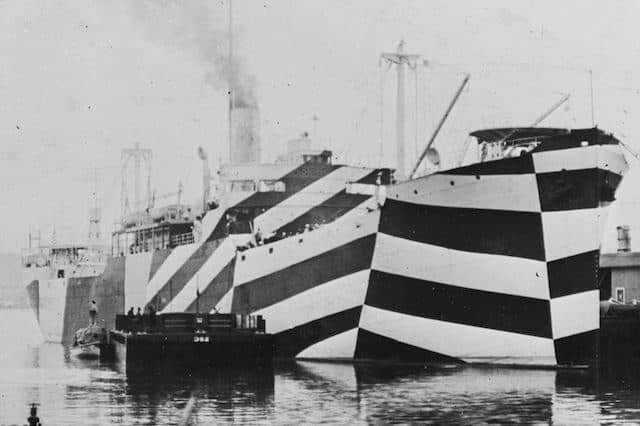

One simple but surprisingly effective defense, dreamed up by a British artist named Norman Wilkinson, was the use of dazzle camouflage. By painting Allied ships in bold geometric shapes and patterns, it was possible to hide them in plain sight. This simple yet ingenious innovation made it difficult for U-boat crews to judge the heading and distance of their targets.

A more aggressive countermeasure was the introduction of Q-ships. These heavily-armed ships were disguised to resemble harmless merchant vessels. They delivered a nasty shock to many unwary U-boat crews expecting easy kills, and were one of the reasons cited by the Germans for their decision to abandon the niceties of Prize Rules.

7. The Lusitania’s Explosive Secret

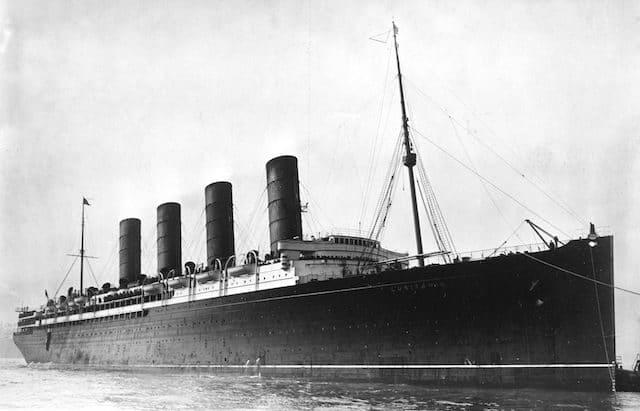

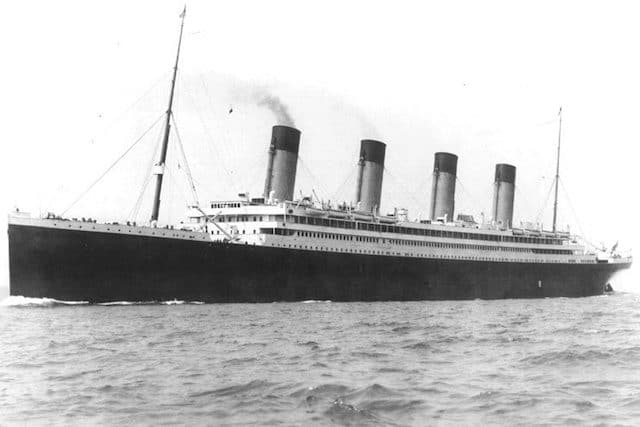

Transatlantic liners had been ferrying passengers and goods across the Atlantic Ocean for decades, and even the outbreak of World War One didn’t put an end to what was a lucrative business.

In March 1915, following Germany’s decision to begin a campaign of unrestricted warfare, notices from the German Government began to appear in American newspapers. They warned that anybody traveling to Great Britain did so at their own risk. One such warning even appeared on the same page as an advert for the Lusitania, the fastest, most luxurious liner afloat, which would soon be making the crossing from New York to Liverpool.

The Lusitania would be steaming into a warzone through U-boat infested waters, but very few passengers were worried enough to cancel their tickets. Cunard Liners, the ship’s owners, assured them the Lusitania was simply too fast for any U-boat to catch. Passengers weren’t told that one of its boilers was out of operation, significantly cutting the huge liner’s top speed.

On May 7, 1915 the Lusitania was attacked by a German U-boat. Just 18 minutes after a torpedo struck, she sank off the southern coast of Ireland. More than a thousand people lost their lives in the disaster, including 128 Americans.

That the Germans would attack a defenseless passenger liner provoked outrage around the world and pushed the United States of America closer to war.

It wasn’t until 2014, after almost a century of denials, that the British Government finally admitted the Lusitania had secretly been carrying millions of rounds of ammunition in addition to her human cargo. She had been, as the Germans had claimed, a legitimate military target.

6. Breaking the Blockade

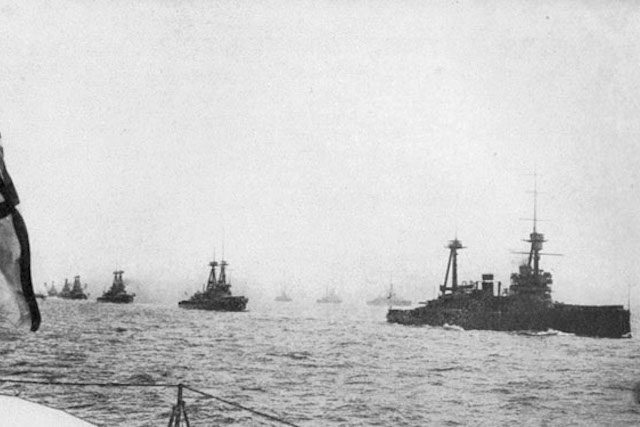

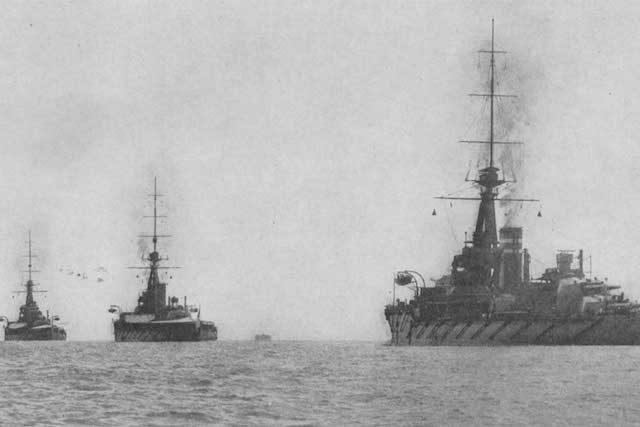

At the outbreak of war in 1914 the German Imperial High Seas Fleet was the second largest navy in the world, with more of the new dreadnought class battleships than France and the United States combined.

The problem was that Britain’s Royal Navy was substantially stronger still, and Germany’s geography made it decidedly difficult to get any surface ships past the superior British force and into the Atlantic Ocean. Britain almost immediately established a naval blockade; any German ships attempting to break the blockade would be sunk, while ships belonging to neutral nations were prevented from trading with Germany.

It took some time for the blockade to have much impact, but it eventually became devastating as Germany ran desperately short of food, fuel, medicines, materials, and even horses.

In 1916 the Germans deployed one of their U-boats, the Deutschland, as a blockade runner. The submarine successfully returned from the United States loaded with 750 tons of chemicals and medicines worth more than $1.5 million. It was the first time a submarine had ever been used as a merchant vessel.

While the supplies were welcome, they were a drop in the ocean compared to what was needed. It wasn’t practical to build a merchant fleet out of submarines, and any effort to do so distracted from the essential business of sinking Allied ships. After a second successful supply run the Deutschland was converted into a military submarine.

5. Most U-boat Attacks were made from the Surface

It’s tempting to imagine that World War One submarines would have spent a great deal of their time underwater, but that’s not the case.

While modern nuclear-powered submarines can theoretically remain submerged for as much as 25 years, submarines of the early 20th century only had around 72 hours of air supply. An even more immediate restriction was the fact that they had to surface after just two hours to recharge their electric motors.

U-boats are perhaps best thought of as torpedo boats with a diving capability rather than true submarines. They weren’t designed to remain submerged or at sea for long periods of time, so U-boat crews had to make their limited supplies of food, fuel, and ammunition last for as long as possible.

With early U-boats carrying a very limited number of torpedoes, U-boat commanders often preferred to attack from the surface with their deck guns if the potential victim didn’t look too dangerous. Perhaps surprisingly, the majority of the ships lost to submarine attack in World War One were sunk from the surface.

4. The Titanic’s Sisters

A little more than two years before the outbreak of World War One, the Titanic crashed into an iceberg in history’s most infamous maritime disaster. She was, however, survived by her two sister ships. While the Olympic and the Britannic have been overshadowed by their more famous sister, the three were designed to be almost identical.

For the early part of the war the RMS Olympic, repainted in a dull grey color and with a strict blackout enforced by night, continued to serve as a transatlantic liner. As the threat of submarine attack rose, in October 1914 the Olympic returned to port in Belfast, where her owners intended for her to wait out the war. It was not to be.

By 1915 the Royal Navy was already running short of ships; the Olympic and the Britannic, which had only recently been completed, were requisitioned for military service.

The Britannic was converted into a hospital ship, but in November 1916 she struck a mine and sank. Fortunately, she was carrying a full complement of lifeboats and only 30 lives were lost. Olympic was more successful than her sisters and covered a distance of more than 180,000 miles over the course of the war. However, on May 12, 1918, while transporting soldiers across the Atlantic, she ran into a surfaced German U-boat. The Olympic was not noted for her maneuverability, but she nonetheless succeeded in turning, ramming, and sinking her assailant. She survived the war before eventually being broken up for scrap in 1935.

3. The Germans Destroyed more than 5,000 Allied Ships

The Battle of the Atlantic was fought in both World War One and World War Two, but the second version is by far the best known. Despite this, the German U-boat campaign arguably came closer to strangling Britain to defeat during World War One.

Between 1914 and the armistice of 1918, the Germans destroyed more than 12 million tons of Allied shipping, made up of around 5,000 individual vessels, for the loss of just 178 U-boats. This works out to around 235,000 tons of Allied shipping destroyed each month. In World War Two, by way of comparison, Hitler’s U-boat fleet averaged a significantly lower 206,000 tons per month at a cost of 784 U-boats.

The decisive difference between the two campaigns was arguably the use of aircraft. In World War Two they were deployed extensively to hunt down and destroy German U-boats. In World War One they lacked the range and the technology required to succeed in such a role. While hundreds of aircraft were used in support of convoys on the last leg of their journeys to Britain or France, there is only one instance of a World War One U-boat being destroyed from the air.

2. The Convoy System Saved Britain from Defeat

On April 6, 1917, the United States of America declared war on Germany. It was a decision influenced, at least in part, by anger at Germany’s campaign of unrestricted submarine warfare.

The British and French had gained a powerful new ally. All they had to do now was hang on until American manpower and industrial strength made victory inevitable. However, it was by no means clear whether they would be able to do so. On land the two sides were still locked in a stalemate on the Western Front, but at sea German U-boats were inflicting appalling damage.

In March 1917, U-boats sank 580,000 tons of shipping. April was even worse, with losses hitting a record high of almost 900,000 tons. If the destruction continued at the same rate, Britain would lose the war within a matter of months.

One proposed solution was that merchant ships could travel together in groups under the protection of warships. This was not a new idea, but senior naval commanders had successfully fought against the implementation of a convoy system throughout the entire war. They argued that convoys would be ineffective, and many of them didn’t like the idea of the glorious Royal Navy taking on such menial work as shepherding merchant vessels across the seas. Eventually, faced with mounting losses and political pressure they were forced to relent.

Convoys were introduced in May 1917, and the impact was immediate. Losses to Allied shipping more than halved, while the number of U-boats being sunk increased. U-boats would continue to be a threat until the end of the war, but there was no longer any possibility of them forcing Britain to surrender.

1. Lessons were not Learned

The U-boats had brought Britain perilously close to defeat, and under the terms of her surrender Germany was banned from building any more submarines. The Nazis had no intention of abiding by these restrictions, and having seized power they began to rearm Germany until she bristled with guns.

A new fleet of U-boats was commissioned, but a dangerous sense of complacency had settled over the British. The Royal Navy believed that U-boats had been rendered all but obsolete by the advances in ASDIC, now known as sonar, which enabled submerged submarines to be detected. Defenses were further weakened by a new offensive doctrine that would draw warships away from convoys, in what were usually futile attempts to actively hunt down enemy U-boats.

At the outbreak of war it quickly became apparent that ASDIC was nowhere near as effective as the Admiralty had believed. It didn’t work well in rough seas, and it was entirely useless when U-boats attacked from the surface – which they usually did.

The British were fortunate that the Nazis had also failed to properly learn the lessons of the First Battle of the Atlantic. Neither Erich Raeder, Grand Admiral of the German Navy, nor Adolf Hitler had any great knowledge of or interest in submarine warfare. As a result the Nazis embarked on a naval rebuilding program that prioritized large, expensive warships over the much cheaper and more effective U-boats.