The Gallic Wars, waged between the Gallic tribes living in present-day France and Belgium and the Roman Legions under Julius Caesar, took place between the years 58 BC to 50 BC. These wars are what ultimately gave Caesar the upper hand over the Senate and his former political ally Pompey the Great, leading in turn to a civil war; the outcome of which made Caesar “dictator in perpetuity” over the entire Roman Republic. But like most conflicts throughout the ages, the Gallic Wars weren’t as straightforward as they may first appear.

10. Biased Sources

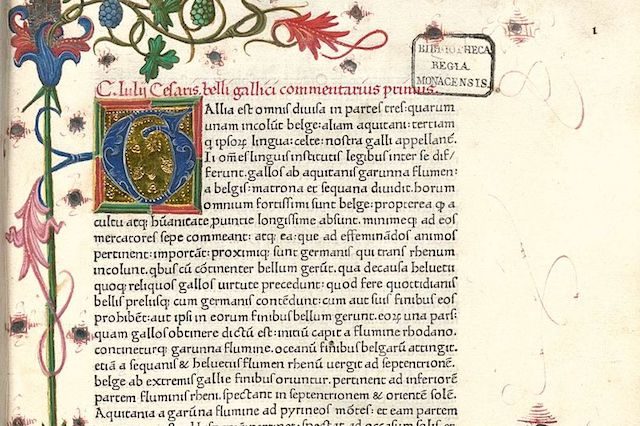

No doubt you’ve heard Winston Churchill’s famous quote that “History is written by the victors,” as was the case with the Gallic Wars. In fact, much of what we know about them comes directly from Julius Caesar himself, in his works (with the exception of the last volume) entitled Commentarii de Bello Gallico, or Commentaries on the Gallic War. When it came to his political affiliations, Caesar was a member of the Populares, a demagogue or populist in today’s terms. They were in direct opposition to the Optimates, or aristocrats, who were also the dominant group in the Senate. Both groups were comprised of members of the wealthier classes, but differed by the means through which they sought tribunician support. While the Optimates were upholding the oligarchy, the Populares sought popular support against it, either for the interests of the common people or for their own personal ambitions. It should be no surprise, then, that the Commentaries were, at least in part, nothing more than propaganda.

But what makes any piece of propaganda great is the fact that it doesn’t sound like propaganda. And the fact that these works, written by Caesar himself about his own exploits (but in the third person), does give the impression of a more objective piece of text than it actually is. Caesar was fully aware that his works were to be read to the masses in city squares and he designed them as such. Even Senator Cicero praised the way in which the texts were written, saying that: “The Gallic War is splendid. It is bare, straight and handsome, stripped of rhetorical ornament like an athlete of his clothes. … There is nothing in a history more attractive than clean and lucid brevity.” In other words, these Commentaries, which were issued every year during the campaign, are not so much historical texts, but rather a means to impress the Roman working class with a sort of action-packed story, if you will.

However, Cassius Dio, a Greek historian who focused on the later years of the Roman Republic and the start of the Empire, was quick to point out several inconsistencies and omissions from Caesar’s works. In the last book, written by one of Caesar’s colonels, Aulus Hirtius, there are mentions of unsuccessful Roman campaigns, as well as the execution of defeated enemies; things never mentioned in the previous works. There are also no mentions of lootings of Gallic sanctuaries or of POWs being sold into bondage. The reasons being that if a general were to sell people into slavery, the Senate was entitled to its own share of the revenue. If there wasn’t any mention of it, Caesar could keep all the spoils for himself.

Lastly, there are examples of intentional mistakes throughout these works that were consistent with the oftentimes fantastical ideas the average Roman citizen had about the ‘edges of the world’. The general prejudice at the time was that the farther inland you went from the shores of the Mediterranean, the more savage the peoples were. Caesar was aware of this fact, and wrote his works accordingly. But even though the bias is evident throughout these Commentaries, they aren’t without value. The focus was placed primarily on the military aspects of the campaign and as far as ancient warfare goes, the Bello Gallico is an important source.

9. Julius Caesar’s Backstory

An important historical figure such as Julius Caesar cannot be accurately depicted in just a few lines (as we will try to do here), but it is, nevertheless, important to know a few details about the man in order to properly understand the Gallic Wars. He was born sometime around 100 BC to a noble Roman family. After his father’s sudden death, Julius Caesar became the head of his family at the age of 16. As a young man, he served for two years in the military, where he won a Civic Crown – Ancient Rome’s equivalent of the Medal of Honor.

In 79 BC he returned to Rome to a civilian life. Due to his charm, charisma, and extensive knowledge of the law, he quickly rose through the ranks of the Republic’s political scene. Back in those times, being a member of the political system came without pay, and going up through the ranks oftentimes meant paying out of pocket. Caesar’s family was also going through some hard times during his ascension, which meant that he acquired some enormous debts financing 180-day celebrations and gladiator fights as Aedile of Rome, among other personal publicity campaigns (which is what they actually were).

In his 30s, he was sent to Spain to hold an administrative office. There, he reportedly came across a statue of Alexander the Great, where it is said that he was feeling dissatisfied with his own life, realizing that Alexander, at his age, had conquered the world, while Caesar accomplished almost nothing. At the age of 40, he ran for the position of Consul, the highest in the Roman Republic. With the people backing him, and with the right connections, he was able to get it. While in office, he bullied legislation through in order to serve him and his political allies. It was also customary for former Consuls to become provincial governors after their terms ended, and Caesar was looking forward to this position.

This way he could leave Rome and escape the possible repercussions for some of the acts he did while Consul. And while governor of a province, he could once again become rich by extorting money from the peasantry there. Caesar was initially given two provinces to govern – Illyricum, along the east coast of the Adriatic Sea, and Cisalpine Gaul, located in Northern Italy. Then, after the Governor of Transalpine Gaul (southern France) died, he was given that, too. Now, what Caesar lacked most of all was glory in the eyes of the Roman people, as well as enough wealth to replenish his coffers. Both of these were possible through war.

8. The Populist Appeal for the Gallic Wars

Back in Caesar’s times, the ordinary person saw war in a much more favorable light that we see it today, partially because the average citizen had more to gain from war than we do today. Waging war on the tribes of Gaul came with an added bonus in the eyes of the average Roman, on top of the spoils and glory it had to offer. You see, several centuries prior to the Gallic Wars (in 390 BC, to be exact), Rome was sacked by the Senones tribe, led by chief Brennus. The whole thing started one year earlier, when this Celtic tribe advanced into Etruria and besieged the Etruscan city of Clusium.

The Etruscans asked Rome for help in dealing with this threat. The sons of the influential patrician Fabius Ambustus were sent as envoys. During the negotiations, however, one of the Fabii brothers killed one of the Celtic chieftains, which was an obvious transgression. The Gauls then retreated to deliberate what to do next. Later that year, Gallic ambassadors were sent to Rome, where they asked the Senate to hand over the Fabii. But even though the Senate was more in favor of this peaceful solution, the influence of the Fabii, who were also elected as consular tribunes and given the command of the army, ensured that this would not happen.

The Gauls then advanced on the city and in July, 390 BC, the two armies faced off at the confluence of the rivers Tiber and Allia, 10 miles north of Rome. The size of the armies varies considerably, depending on the sources and other modern interpretations; so much so that we can’t even say for sure who had the numerical advantage. Nevertheless, the outcome of the battle is known, and it concluded with a definite Roman defeat at the hands of the Senones. One day later, the Gauls made it to Rome, which was unprotected and with its gates wide open. Only the Capitol Hill could be defended, while the rest of the city was reduced to ruins.

Many Roman citizens were able to escape during the night past the unsuspecting Gauls. After seven months of sieging the Capitol, and burdened by famine and disease, both parties finally decided on a ceasefire where the Romans would pay 1,000 pounds of gold. This defeat ensured an enduring hate for the Gauls in the eyes and minds of the Romans for centuries to come; something that certainly added to their support of the Gallic Wars more than 330 years later. This event in Roman history also gave them a wakeup call, leading the Romans to greatly reinforce their city defenses and develop an army never before seen in the ancient world.

7. Who were the Gauls?

Gaul was the name given to the regions where various tribes of Celts lived, north of the Roman territories. These included France, Belgium, Luxembourg, Switzerland, parts of the Netherlands, parts of Germany west of the Rhine River, and Northern Italy. But as a group of Indo-European nomadic or semi nomadic people, these Celts extended at various times over large parts of Europe including in Britain, Illyria, the Iberian Peninsula, the lower Danube River Basin, Transylvania, and even as far east as Asia Minor – present-day Turkey.

What rather vague information we have about these people comes mostly from the Greeks and Romans. They were, nevertheless, described as tall and possessing great physical strength. They had fair skin and blonde hair which they would usually redden by artificial means. Gallic women were described as the most beautiful of all barbarian peoples, and they could hold their own in battle. Most Gauls wore little to no defensive armor. Their usual means of defense was the helmet and the shield, which came in various shapes and sizes. Wealthier warriors also wore a chainmail shirt, of which they are the supposed inventors. Gauls mostly preferred the two handed sword, but also had various kinds of spears, pikes, javelins, bows and slings. They placed a lot of faith in their cavalry, and in the northern parts of Gaul, they even used war chariots. The foot soldiers were arranged in great masses that loosely resembled a Greek phalanx with a line of shields in front, to the sides, and overhead. In the thick of battle, it was customary for champions to break these ranks and challenge opponents to single combat.

Nevertheless, it would be a mistake to think of Gaul as a unified nation. They are better described as a loose confederation of tribes, around 60 in number, which oftentimes fought against each other over lands or other disputes. These tribes also varied greatly in power and influence, with smaller tribes maintaining only a nominal independence under the protection of bigger ones. What kept them together, as much as they were “together,” were the somewhat similar customs, consanguinity, language (to a certain extent), and a similar religion. The region was home to roughly 15 to 20 million people, but because of this disunity and intrigue among them, Caesar and his legions were able to successfully challenge them.

6. Casus Belli

Like any war, the Gallic Wars needed a motive, or at least a pretext, to be initiated in the first place. As a governor in charge of provinces located at the fringes of the Republic, Caesar was given several Legions to protect them and their interests, but he couldn’t just start attacking neighboring tribes without just cause. Many of these tribes were, in fact, allies of Rome and these relations needed to be maintained. Nevertheless, Caesar’s casus belli (case of war) came in the form of the Helvetii, a Celtic tribe in what is now present-day Switzerland. Together with several other neighboring tribes, they decided to migrate en masse from that region and into Gaul proper to the west, numbering somewhere around 320,000 people strong, probably even more. These weren’t just able men and soldiers, but the entire population including women, children, and the elderly.

Now, regardless of Caesar’s personal motives for starting a war, a mass migration so close to his borders, and through his lands, could have caused a serious instability for the entire region. For starters, just by walking around, so many people could seriously damage the countryside they were passing through. Secondly, once they reached a place, they would displace other tribes from their lands, which in turn would kick start a chain reaction throughout the entirety of Southern Gaul and even into Transalpine Gaul – the Roman province under Caesar. Lastly, the vacuum left behind in Switzerland posed another threat for Rome, since it would have opened it up to other tribes, probably the Germanic Suebi. Rome preferred the Gallic Helvetii there to act as a buffer. In Caesar’s reports to the Senate, he stated that the Helvetii chief Orgetorix formed a secret plot with several other Gallic chieftains to band together and take over the whole of Gaul for themselves, and then, probably, to drive back the increasing threat Rome was posing. Also according to Caesar, this plot was foiled and Orgetorix committed suicide before he could be put on trial.

But despite their chieftain’s death, the Helvetii went on with their migration, most likely pushed by the Germanic people to the north. They did ask permission from Caesar to pass through his lands, but he refused. They then decided to head north without trespassing through Roman territory. Even though Roman lands were no longer under threat, Caesar chased after the Helvetii and attacked them on two occasions, inflicting heavy losses. The remainder of their people were then forced to return to Switzerland. With his forces now on the move, Caesar’s Gallic Wars had begun.

5. Ariovistus – The Germanic War Chief

Even though Caesar used the Helvetii to get his legions into Gaul, he also needed a motive to keep them there. In fact, every new engagement he was involved in over the course of the following years needed something to justify it. And this time it was Ariovistus, a Germanic Suebian chief who crossed the Rhine River into Gaul. Shortly after his victory over the Helvetii, Caesar received a delegation of Gallic leaders, asking him to help them against the Germanic aggressor. Ariovistus initially came to Gaul at the request of the Sequani, in order to help them against the Aedui, with which they were fighting about tolls on the Saone. The Aedui, who were allies of Rome, had asked the Romans for help in 61 BC, but the Romans were unable to help because of an uprising that sprang up. Ariovistus initially came with 15,000 men and helped the Sequani win their war, but soon enough began making harsh demands like two thirds of their lands. By 58 BC, the Germanic numbers swelled from 15,000 to 120,000, in order to populate the area west of the Rhine River, and with plans to bring even more.

After two unsuccessful negotiations with Ariovistus, Caesar moved quickly to take over the Sequani capital of Vesontio before the Suebi could. In doing so, the two armies got in striking distance of each other, and this was the first and last time the Roman soldiers almost went into a panic, based on the stories they heard about the Germanic tribesmen. Nevertheless, after a few days’ rest, Caesar went in pursuit of Ariovistus and caught up to him after a week of relentless marching. Ariovistus was then able to go around Caesar and set up camp behind him on top of a hill, in a position where he could intercept the Roman grain supplies. Caesar moved back behind the tribesmen and built a fort there, all the while keeping the construction safe from raids. But after successfully interrogating a prisoner, Caesar found out that Ariovistus was avoiding a full battle because of a divination that said that the Germans would not win before the next full moon. In what could be described as a self-fulfilling prophecy, Caesar initiated a battle before the new moon, resulting in their victory. The retreating Germanic forces crossed the Rhine, and it would be three years before Caesar faced them again.

4. The Bravest of the Gauls

In his Commentaries, Caesar names the Belgae as the bravest of all the Gallic tribes. Now, these Belgae weren’t a single tribe, but an entire confederation of over 20 tribes that inhabited the region northeast of present-day Paris and into present-day Belgium. The reasons Caesar called them as such is mainly to reinforce the preconceived notion that the farther away one went from the Roman sphere of influence, the more barbaric the tribes became. That, plus the fact that the Belgae bordered the Germanic tribes to the east, meant they were in constant conflict, and in turn made them accustomed to war (which wasn’t an entirely false assertion by Caesar). Nevertheless, Belgica was the next region Caesar and his legions went into next.

Some rumors reached Caesar after his campaign against Ariovistus that the Belgae were amassing a large army as a response to his earlier conquests, and the fact that his legions hadn’t left Gaul after those conflicts were over. And they were right to be alarmed. The following year, in 57 BC, Caesar returned to Gaul with two new legions that he raised during the winter months, raising his forces to eight legions, or 35,000 to 40,000 men. It is important to note that Caesar was initially given four legions to defend his provinces, but had now doubled his forces without the approval of the Senate. Hearing of the Belgae army, he marched into their territory. Here, the two armies battled it out twice, once at the River Sabis, and another at Axona River. Even though the Romans were victorious on both accounts, Caesar had suffered some heavy losses, particularly at the Sabis. This was also the hardest battle fought during the entire Gallic Wars, with the exception of a last stand that was to follow years later.

Caesar then marched his troops all throughout Belgica, subduing one tribe after another, either through sieges or volunteered surrender. Now even though it’s not mentioned, it is safe to assume that a lot of pillaging took place during this period, as well as throughout the entire Gallic campaign. Caesar also wintered his legions in Belgica, spreading them out among the various tribes. This, of course, felt like (and indeed was) more of a subjugation than a temporary thing. In 53 BC, a northern tribe known as the Eburones revolted against this oppression and abused 15 cohorts stationed there. In retaliation, Caesar virtually exterminated them, which opened the door for some Germanic tribes to cross the Rhine and replace them.

3. The Veneti and Sea Warfare

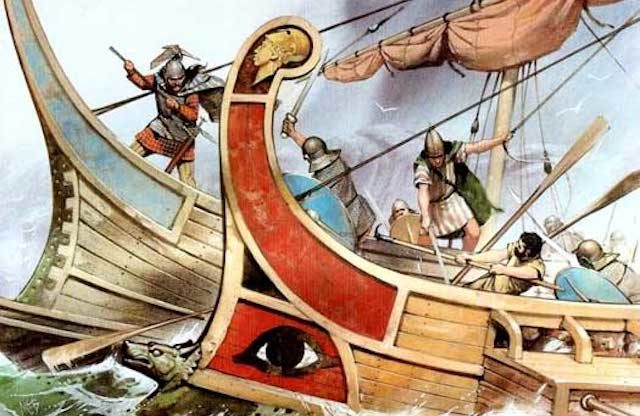

Caesar’s pretexts of waging war all across Gaul were becoming weaker with each passing year. When it came to the Veneti, a northwestern tribe located mostly on the Atlantic coast of Brittany in France, a simple case of diplomatic misunderstanding was enough to make Caesar declare war on them. The only problem was that the Veneti were a seafaring people and some of their strongholds were protected by the tide itself, somewhat similar to Mont Saint-Michel in Northern France. In preparation for this war, Caesar ordered some 200 ships to be built on the Loire River that connected with the Atlantic. And while Caesar marched with his legions on foot toward Veneti territory, the ships went downriver and up the coast.

Hearing of their coming, the Veneti boarded their ships and fled offshore. When Caesar arrived, he found only deserted villages, which he then pillaged and burned. The Roman ships, unlike the Veneti ones, weren’t built for the Atlantic, which meant that the Veneti could outmaneuver them. Roman naval battles were based on ramming the enemy ship, crippling it, and then boarding it. But the Veneti weren’t only faster and had better knowledge of the tides, but their ships were also sturdier – which made them impossible to successfully ram and cripple. Their ships were also taller than the Roman ones, so if the Romans got close, the Veneti could easily shower them with arrows and other projectiles. To overcome this problem, naval commander Decimus Brutus (one of the men who would later take part in Caesar’s assassination – though he wasn’t that Brutus) came up with an ingenious idea to incapacitate the Veneti ships. By making use of some hooks on long poles, the Romans were able to tear down their sails, making the enemy ships dead in the water. They were then able to board the ships and win the battle – all while Caesar watched from the beach.

With the fleet gone, the Romans now could effectively storm those strongholds and finally crush the Veneti. In the aftermath, the elites were killed while most of the rest of the population was sold into slavery. This grim fate of the Veneti served as an example for the rest of the tribes in the region about the might of Rome.

2. Caesar in Britain

Throughout the Gallic Wars, Caesar became the first Roman who officially crossed the Rhine River, and the first to go to Britain. But while his crossing into Germanic territory was more of a show of force and he didn’t actually encounter anyone, his visit to Britain was different. He actually went there on two separate occasions. His reasons for going there were, as usual, very implausible and unconvincing. In his Commentaries, he said that the people living there were aiding the Gauls he was fighting on the mainland. For the Romans back home, they only heard rumors about the island, with all sorts of stories made up about it – some of which being that it was the land of the dead. So, you can imagine what a great PR campaign this was for Caesar. Nevertheless, in his first crossing of the English Channel, he only did so with two legions, or roughly 10,000 to 12,000 men. Even though this was more of a reconnaissance expedition, it could have been a disastrous one for Caesar.

When his fleet reached the British shore around Dover, he was met with a formidable Briton force up on the hill. What’s more, his cavalry forces weren’t able to make the crossing because of high tides. When the actual landing took place, the Romans were met with a fierce resistance and suffered heavy losses. They were able to put together a defensive position just off the beach, but with little supplies available the campaign only lasted for 20 days before they had to return to the mainland. The most formidable weapon the Britons had at their disposal was the war chariot. With it, the Britons were able to effectively deploy constant hit-and-run tactics, harassing the Romans at every turn. The chariot was driven by one man while two others were throwing javelins. If necessary it would stop, the men would get off, and fight on foot. But if the battle became too fierce, they would get on again and ride away. And because the Romans didn’t have their cavalry with them, they couldn’t actually fight back against them.

Nevertheless, this incursion to the British Isle was widely celebrated in Rome, so Caesar decided to return in 54 BC. This time, however, he would bring five legions and 2,000 mounted troops. And while they faced similar difficulties as the first time, they were able to storm the Catuvellauni stronghold, the most powerful tribe in southern Britain. After securing a peace treaty and annual tributes, Caesar returned to Gaul. The Romans would not set foot in Britain again for the following 90 years.

1. Vercingetorix

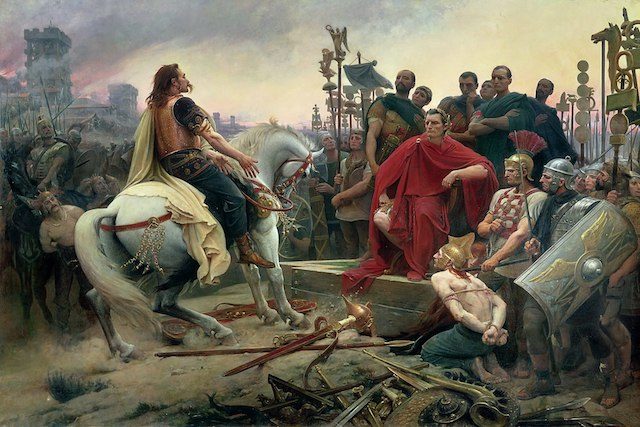

As Caesar’s grip tightened over Gaul, the people living there were feeling the effects and were beginning to conspire against the Romans. Even though the annexation wasn’t official, the many Gallic tribes had to pay Caesar annual tribute, give him fighting soldiers, and supply him with grain. Many Gallic leaders came together and decided on a coordinated Gallic rebellion all across Gaul. One man, Vercingetorix, was chosen to lead this revolt. This revolt consisted mostly of guerrilla-style warfare where there were many hit and run operations and a scorched earth policy implemented wherever the Roman legions went. After a series of successful encounters, Vercingetorix was pinned down at the fortress of Alesia in 52 BC.

In charge of some 60,000 men and having the advantage of higher ground, Vercingetorix decided to wait for reinforcements. Caesar was at another disadvantage since his supply lines were unreliable while they were going through enemy territory. Nevertheless, knowing that another Gallic force could be arriving at any given moment, he began construction on a circumvallation wall surrounding the entire hill fort. After that was finished, he began working on another one, but this time facing outward, and with his army in between. When the Gallic reinforcements finally arrived, battle commenced almost immediately. And after several days of engagements, with the Romans being pinned in the middle, they were almost overrun. In a last-ditch effort, Caesar ahead of his 6,000-strong cavalry was able to break through the lines and attack the Gauls from behind, eventually winning the battle. With no real chance of escaping, Vercingetorix surrendered the following day.

While the Battle of Alesia is the official end of the Gallic Wars and the region’s annexation into Roman territory, a mopping up operation took place over the following year and a half. And even though there were several other uprisings, Roman control in Gaul was not seriously challenged until the second century AD. In the aftermath of these wars, over one million people lay dead and another 500,000 were sent into slavery. With the wealth and forces Caesar accumulated over this period, he was also able to challenge his former ally in Rome, Pompey Magnus, as well as the Senate, and initiate the following Civil Wars that would effectively put an end to the Roman Republic and pave the way for the Roman Empire to arise.

1 Comment

Caesar did mention selling pows to slavery, many times