We know what impressive armies Ancient Rome could field, as brutally treated as the troops were. Curiously, though, most TopTenz articles have focused on times they lost. In fact we’ve done whole lists of them. It’s enough to make you wonder how they ever conquered an empire which stretched from Great Britain to the Persian Gulf.

It’s time to give the long-suffering legionnaires their due. Sure, they oppressed much of Europe, the Middle East, and Africa. But in battle after battle, war after war, they showed that in at least one way they were some of the finest soldiers in the World.

10. Beneventum (343 BC)

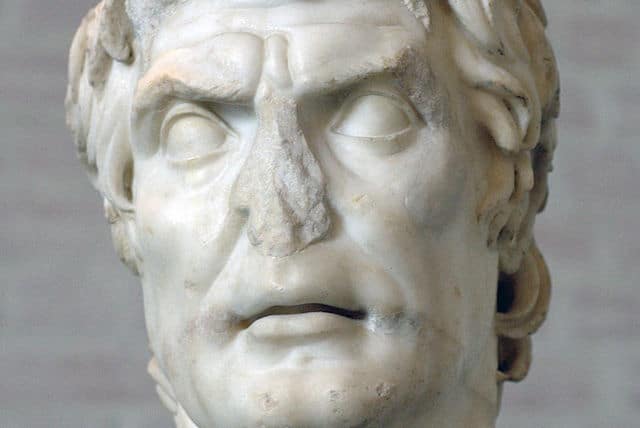

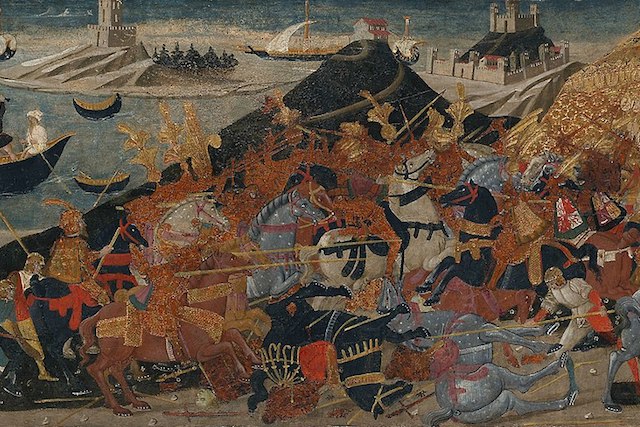

There was no rapid, stunning early success for the Roman Empire as there was for the Mongols with Genghis Khan. In the early 4th Century BC, the Gauls conquered the city of Rome itself. Yet the Romans recovered, and by the mid-3rd Century BC they once more were such a powerful presence on the Italian Peninsula that Pyrrhus of Greece was called upon to lead an army of roughly 25,000 against them. The Romans lost twice to him as he came within 40 miles of attacking Rome, but seemed to find a curiously effective strategy in their loses: They inflicted so many casualties on the Greeks in their losses it weakened Pyrrhus’s ability to wage war, and effectively coined the concept of the “pyrrhic victory.”

In 275 BC, Pyrrhus got word that an army under Consul Manius Dentatus had been dispatched from Rome, and were near a wooded area close to the city of Beneventum. Eager to ambush the Romans, Pyrrhus sent the Greeks on a night march through the forest, and by a stroke of bad luck many of the Greek torches went out and they became hopelessly lost near the Roman camp. By the time they had reconverged, the Romans had caught wind of their presence, and knew from experience fighting disciplined Greek Phalanx formations that the best hope was to meet them on broken forest ground were they couldn’t form impenetrable shield walls.

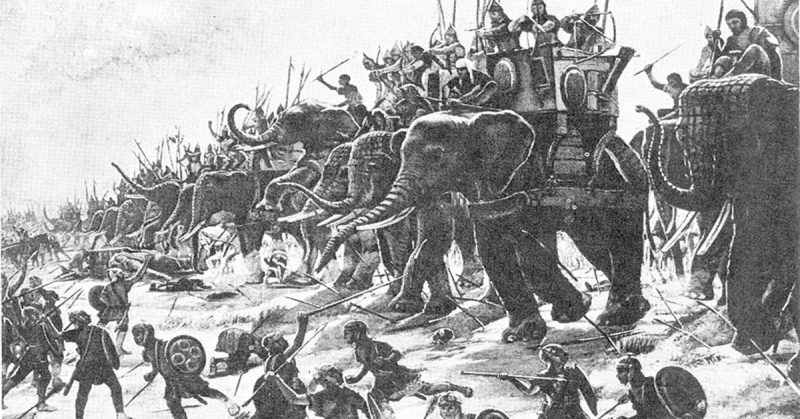

While the Romans were able to trap Pyrrhus, the Greek leader still had a secret weapon up his sleeve: A contingent of elephant-riders that he launched into the Roman lines. While initially the elephants were able to break the Roman ranks, the Romans turned to a cleverer strategy than trying to kill the elephants. Using threatening but nonlethal volleys, the Romans were able to herd the animals into charging back to the Greek ranks in the woods and shatter Pyrrhus’s ranks. His allies in Southern Italy abandoned him, and Pyrrhus was forced to keep running until he returned to Greece.

9. Metaurus (207 BC)

As we’ve explained elsewhere, during the 2nd Punic War after his march from Spain over the Alps to Italy Hannibal was able to inflict devastating defeat after defeat on the Romans for the Carthaginian Empire, most notably when he destroyed a significantly larger Roman army at Cannae in 207 BC. So the situation was already bad enough for the Romans before Hannibal’s brother Hardusal also crossed the Alps and arrived in Italy with tens of thousands more troops to march on Rome. The Romans risked transferring 7,000 troops that were desperately needed to hold off Hannibal up to their northern armies. The northern Roman army confronted Hardusal along the Metaurus River. Hardusal took some high ground the secure the left wing of his army, then attacked the Romans hard on their left, confident his own left would hold.

As it happened, the General Nero (no relation to the Emperor when Rome burned) also believed the Carthaginian left wing would hold if he attacked it as conventional strategy demanded. So instead, he marched his 7,000 behind the back of the Roman army, then charged around the Carthaginian right wing. The result so completely smashed the Carthaginian army that Hardusal was unable to escape with his life. According to historian Edward Creasy, this was literally one of the most decisive battles in human history for how it saved the Roman Empire. He related this in his 1851 work The Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World, a book which goes to show that lists of historical events have a long, proud tradition which TopTenz helps to uphold.

8. Ilipa (206 BC)

Accepting that Hannibal was too dangerous to face in the field even after the death of his brother, the Romans concentrated on attacking the Carthaginians in Spain to cut off Hannibal’s flow of supplies and potential reinforcements. Under the general that would become known as Scipio Africanus, the Romans inflicted the most devastating Carthaginian defeat of the war near the present day site of Seville, Spain.

Numbering roughly 55,000 to 45,000 in the Carthaginians favor, the two armies felt sufficiently evenly matched that neither side rushed into battle, preferring initially to engage in light skirmishes. Twice in two days the two armies arrayed themselves in the same ways, and for the third day, Scipio had the idea to completely change the formations of his troops, mostly to favor the flanks of his army, then launched an early attack to draw the Carthaginians into battle before Hardusal could reconnoiter how the Romans had arrayed their troops or feed themselves. The Carthaginians were unable to press their counterattack and eventually collapsed. By some claims, their routed army suffered roughly 49,000 casualties to Rome’s 7,000, and the Iberian Peninsula was lost.

7. Zama (202 BC)

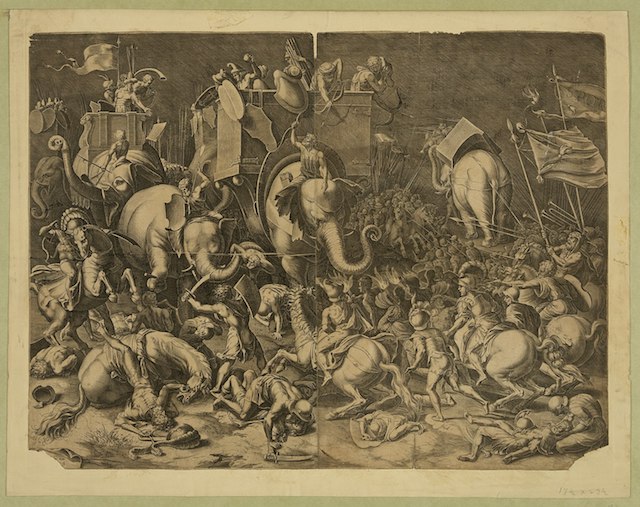

Even with the defeats of Ilipa and Metaurus, Hannibal was still such an effective general that he fought for five more years against Rome. Scipio Africanus had to invade modern day Tunis and march on the city of Carthage itself to draw Hannibal out of Italy where two of the most celebrated generals of their eras could match wits. According to legend there was so much mutual respect that the two generals supposedly had a minor conference the day before, and when Scipio’s men captured a couple of Hannibal’s scouts, Scipio gave them a tour of his army, then released them. If so, they had some mixed news for Hannibal: Scipio had 36,500, of which 6,500 were cavalry. Hannibal had 43,000, of which a fairly limited 3,000 were cavalry, but he also had 80 elephants..

The battle opened with Hannibal ordering his elephants to lead the charge. The Romans spooked the beasts with an especially loud horn burst, and the elephants largely turned and ran into the Carthaginian cavalry formations, both of which immediately broke and retreated when the Roman cavalry attacked (some have argued intentionally to lead the Roman cavalry away from the battle). The Roman and Carthaginian infantry ground each other down until Hannibal committed his veterans from Italy, who began to bend the Roman line before the Roman cavalry returned. Unfortunately for Hannibal they ended up allowing themselves to be encircled when the mounted troops returned at length. Between how well they’d worked at this battle and Beneventum, it was little wonder that this was the last time elephants were pitted against Roman troops in battle for a long time.

6. Aquae Sexitae (102 BC)

At the end of the 2nd Century BC, the allied Germanic tribes were on the move, and hundreds of thousands under King Jugurtha had decided Italy would be their new home. In what became known as the Cimbrian War, the German armies were much more capable than the emerging Roman Empire expected. In 112 BC they utterly defeated a Roman army at the Battle of Noreia, then followed that up in 105 BC with an even greater victory at Arausio, where they wiped out tens of thousands of Roman soldiers. It fell to Consul Gauis Marius’s army to stop the greatest threat to Rome in more than 150 years, first confronting them in Northern Italy at a river valley where he stationed his army to threaten a supply route that the Germans would use for their southward migration.

Outnumbered as he was with 40,000 troops to 140,000 previously very successful Germans, Marius had his army take up a strong position on a hill, dig entrenchments, and forage for a siege while the enemy arrayed itself. According to legend, several German warriors challenged Marius to one-on-one combat, and Marius’s choice reply was to tell them that if they were “tired of life” they should go get a rope. Eventually, the battle escalated when the Germans chanced on a Roman patrol and defeated it, getting their blood up to attack the main Roman force.

Marius’s troops were able to hold the fort, and to the German dismay he had sent a force of 4,000 back around them in a flanking maneuver through nearby woods. When the rear force attacked, the Germans broke so badly that their force was scattered with 80,000 casualties and tens of thousands of prisoners being sold into slavery. A famous anecdote from the aftermath emerged that 300 of the German women chose suicide over bondage. In another act of legendary defiance, it was said that some of the prisoners or their offspring would, down the line, take part in the famous gladiatorial uprisings under Spartacus.

5. Vercellae (101 BC)

As great of a setback for the German allies as Gauis Marius’s first victory was, King Jugurtha still had the bulk of his army and the German people were no less desperate. A second, even more significant battle was inevitable. But by the main historical account, Gauis Marius had to work with Consul Lutatius Catulus, who believed in positioning the Roman Army in the Alps to prevent the Germans from entering Italy proper, a strategy which failed because it left his troops divided in a situation where the Germans could use a number of alternative, less obvious routes to cut off and encircle his forces. The Romans had to fall back and confront the Germans after a large number of them had entered into Northern Italy in the region that became known as Lombardy but before more of their allies could arrive from Central Europe and present a truly overwhelming force. Even as it was, when Catalus and Marius pitched battle against the Germans, it was still their roughly 55,000 against an enemy that conservatively numbered over 180,000.

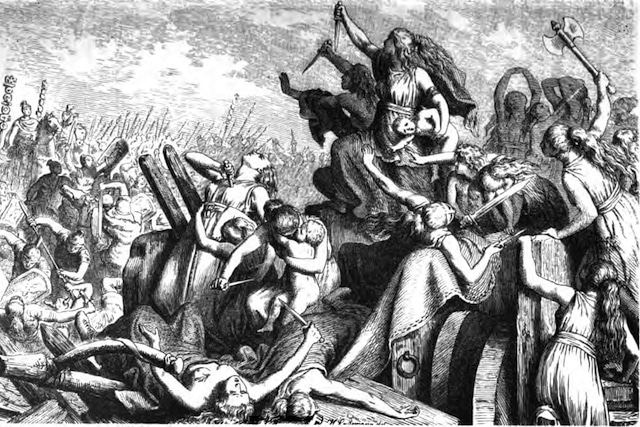

Arraying his troops in mist, the Romans were able to launch a surprise attack against the Germans that left the sun in the eyes of their enemies. The Germans, not being any sort of disorganized horde, launched a cavalry counterattack to flank the Romans on the left. Gaius Marius responded by attacking the gap between the German cavalry and their infantry on the German right, allowing the Romans to cut the flanking force off and hit the German infantry in a vulnerable spot. By some estimates, there were more than 120,000 German casualties in the rout. The German women did themselves prouder than those at Aquae Sexitae, taking up arms and fighting a last ditch effort against the Romans before many of them were taken prisoner and enslaved too.

4. Nola (89 BC)

In the wake of the amazing successes against the Germans, the Roman Senate’s prejudices came to the fore and they attempted to cheat all the non-Roman Italian veterans out of full compensation. This resulted in a needless civil war that came to be known as the Social War. One of the most accomplished Roman generals in this conflict was Sulla, by some accounts effectively Gaius Marius’s right hand man during the Battle of Vercellae. In 89 BC he was charged with laying siege to the rebellious cities of Herculaneum and Pompeii. An army known as the Samnites came to lift the siege. Despite the fact that his army was split between besieging two cities and foraging, Sulla launched an attack. The Samnites were able to hold and then press a counter attack, but in the process they stretched themselves out enough that Sulla’s foragers were able to converge and repulse the counterattack.

The Samnites were able to rally again when a contingent of Gaul allies arrived. However, according to legend, one of their largest soldiers challenged the Romans to one-one-one combat, prompting a particularly short Roman to come up and accept the challenge. To the apparent astonishment of the Gauls the shorter man won, and the Romans were subsequently able to break their lines and the Samnites with them. The routed army was herded towards the city walls of Nola where the Romans were able to cut down roughly 23,000 of them.

Sulla retained the initiative sufficiently to carry his army south to victory after victory until the uprising was put down. On returning to Rome, Sulla and Gaius Marius would develop a rivalry that would cause them to essentially alternate which one of them was the Top Man in Rome. In the process they would kill thousands of each other’s loyalists.

3. Pharsalus (48 BC)

No list of Roman triumphs would be complete without devoting at least an entry to Julius Caesar, and while his greatest triumph was the Battle of Alesia, we’ve already covered that in another list. Instead we’re going to focus on Julius Caesar’s reward for winning the Battle of Alesia: The Senate ordered him to surrender his army. Instead, in 49 BC Caesar marched on Rome and the loyalists to the Senate under Caesar’s old friend Pompey fled to Greece. Caesar pursued, and after a year of maneuvering and counter-maneuvering, it was settled at a hilly area to the Northeast of the city of Pharsalus. Pompey’s troops numbered 45,000 to Caesar’s 22,000, and many of Pompey’s troops were just as battle-tested as Caesar’s.

Caesar’s trick was to lure Pompey’s cavalry into riding around his right flank, but he kept a line of soldiers with pikes in reserve. They were able to flank attack the very cavalry that was supposed to be flanking them. This left a line of Pompey’s archers vulnerable to attack by Caesar’s men, and from there the collapse of Pompey’s army took hold so that Caesar’s troops won the field supposedly in about an hour. Caesar then rushed some legions between the routed troops and their water supply, so that the next morning, the desperately thirsty remnants surrendered without another fight. The casualties were said to be about 15,000 for Pompey’s fleeing army and under 300 for Caesar. There would be additional battles in the civil war, but while Pompey would ultimately be assassinated by the Egyptian Empire he would never again command an army against the new emperor of Rome.

2. Watling Street (61 AD)

The rise of Boudica of the Britons has been covered elsewhere on TopTenz, but there wasn’t full coverage of how the Romans ended her rebellion. The 10,000 soldiers dispatched under Gaius Paulinus could hardly overwhelm the British army of over 100,000 with force, yet the fury with which Boudica had destroyed Colchester and London showed that her army could be manipulated into an attack from an advantageous position. Paulinus selected a gorge which historians have not been able to place precisely. Watling Street, despite its name, was actually a long road that went near modern day communities such as Leicestershire, Warwickshire, and Shropshire — all of which had locations which various historians claimed were the site of the battle. What historians agree on is that the Roman flanks were well-anchored and the routes around the army too heavily-wooded for a loosely organized group of Britons to maneuver through them properly. Besides, the rebels were so confident that they could shatter the limited Roman force with a frontal attack that they brought their families out to watch.

It turned out that the attackers were too densely packed to avoid javelins and other Roman missiles, but also too lightly armed to break through the stout Roman formations. Then the Roman cavalry counterattacked on the flanks. The Britons had made the mistake of arraying a great train of carts behind their attacking lines, which greatly slowed their retreat. According to the Roman historian Tacitus, the Romans ended up killing 80,000 of their enemies while losing only 400 casualties. It must be said the legionnaires reportedly made no distinction between enemy combatants and children in the battle’s aftermath.

1. Chalons/Catalaunian Plains (451 AD)

By the 5th Century AD, the writing was on the wall that the Western Roman Empire was coming to an end. Alaric’s Visigoths and the Vandals had already sacked Rome on separate occasions, and Roman armies were composed at least as much of foreign mercenaries as they were of legionnaires. Still, when the threat of Attila and his Huns arrived in 440 AD, the Romans were able to field the largest army against him and present the only hope their traditional enemies had of stopping the massively successful Eastern European. Even the combined might of Rome and Theodoric of the Visigoths could only field an army at Catalaunian that was vastly smaller than Attila’s 100,000 soldier army. Yet the Roman commander was Flavius Aetius, and he brought considerable guile with him.

In arraying his forces, Aetius laid a trap. He left his center deliberately weak and out in the open. and positioned his strongest forces behind a hill that dominated the battlefield while the Visigoths were on his right wing. When the Huns attacked the weak center and inevitably broke through while pressing hard on his allies, Aetius’s Romans charged downhill into the Hunnish force on the flank, shattering Attila’s breakthrough so badly that the Visigoths were able to join the Romans in the counterattack. Attila’s troops were double-enveloped and driven back into the improvised fortress of their encircled carts.

Beyond the immediate success on the battlefield, Aetius had the extra prize of his Visigoth ally Theodoric dying in battle. This meant he could convince his successor to return to his homeland quickly to ensure he was not usurped by his many rivals to the throne, ending an immediate threat of his allies potentially turning on him now that the Hun ability to wage war was neutralized. It also meant Aetius could allow Attila to sneak away with his depleted army so that while the Huns were no longer a threat to Rome, they were potentially enough of a threat to the Visigoths that they could not risk a war with Rome without the possibility that their homeland would be raided by the Huns while they were crossing swords with the Italians. Such was the cunning of the general who provided Western Imperial Rome its last great victory.

Dustin Koski’s greatest triumph is the fantasy novel A Tale of Magic Gone Wrong.