Starting from humble beginnings, Rome managed to make a name for itself – a name that withstood the test of time. Ancient Rome was a highly militaristic society, enabling it to subdue one tribe after another and stretch its borders to the edges of the known world. Yet, it was that same army buckling under its own weight that eventually brought Rome down. In any case, for all its glory and might, the mighty Roman army did suffer some crushing defeats and we will be looking at some of them here.

10. The Battle of the Allia River (380 BC)

Rome’s first major military defeat came in 380 BC at the confluence of the rivers Tiber and Allia, some ten miles north of the city. It all started when a tribe of Celts from what is now Northern Italy descended upon the Etruscan town of Clusium. The Etruscans asked Rome for help in mediating the situation. After some terrible negotiations, where one Roman envoy killed a Gallic chieftain, the tribesmen retreated in order to deliberate their next move. They then sent ambassadors and asked the Roman Senate to hand over the three envoys, part of the previous negotiation. This did not happen, however, as the three influential Fabii brothers went on to become “military tribunes with consular powers.”

Offended, the Gauls marched their forces from the gates of Clusium and on to Rome. Historical sources contradict each other on the exact size of the two armies and we can’t even say for sure who had the numerical advantage. What is certain, however, is the fact that the Romans were completely crushed under the brute force of the marching Celtic army. Two thirds of the Roman army is said to have perished, either by drowning in the river or being mowed down from behind in their complete panic and disarray.

The Gauls then advanced on the city, plundering and raising it to ground. The majority of the population did manage to escape in the night, however. After several more months of besieging the Capitol Hill and with a disease spreading through their ranks, the Gauls retreated, but only after receiving a hefty ransom. To be fair to the Romans, this battle happened before they began perfecting their army. After it, however, a series of military reforms were enacted, laying the foundation for what was to come.

9. The Battle of Drepana (249 BC)

Following a string of naval victories as part of the First Punic War against the Carthaginians, Rome felt emboldened and eager for a fight. Ahead of 120 ships, Publius Claudius Pulcher, the Roman consul at the time, blockaded the Carthaginian fortress of Lilybaeum, present-day Marsala in western Sicily. Yet despite their best efforts, the Romans were unable to stop some Carthaginian ships from slipping through the blockade in broad daylight and supplying the besieged fortress. What’s more, the Carthaginian ships also made it back through the Roman blockade without a scratch and repeated this maneuver several more times over the following weeks.

Pulcher then decided to launch a surprise attack on the port of Drapana, also in western Sicily, where those ships were garrisoned. The Roman fleet lifted the blockade and left in the dead of night. But because of poor visibility, the Romans reached their destination in a scattered formation and could not effectively perform a surprise attack. Before the battle, Pulcher performed a divination to see whether the gods were on their side. This divination involved several sacred chickens and their feeding behavior. Since the chickens refused to eat, which was a bad omen, Pulcher threw them overboard saying “Let them drink, since they don’t wish to eat.”

In the meantime, the Carthaginians managed to evacuate the port of ships. Because of the local geography, the Romans soon found themselves pinned between the Sicilian coast and the Carthaginian fleet. The naval battle was quick and decisive. Though their numbers were of roughly equal size, some 120 ships each, the Romans lost 93 while the Carthaginians lost none. Pulcher did manage to escape and returned to Rome in shame. He was charged with treason – not for his defeat in battle, mind you, but because of the chicken incident. He was convicted and sent into exile where he died soon after – probably by suicide.

8. The Battle of the Trebia River (218 BC)

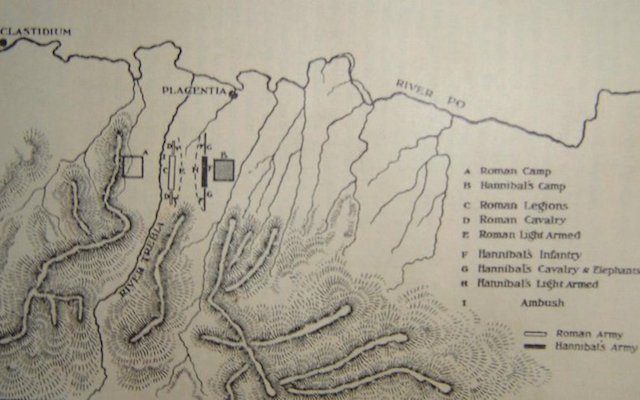

With the start of the Second Punic War in 218 BC, we have the famous Carthaginian general Hannibal march his forces into what is now present-day Spain and over the Alps into Italy. Even though he suffered heavy losses while making the treacherous mountain passing, his ranks were bolstered by the Gauls living under Roman occupation in northern Italy. The Romans sent consul Tiberius Sempronius Longus ahead of several legions to reinforce the already existing troops. The other consul already there, Publius Cornelius Scipio, was the more experienced of the two but was injured during a previous skirmish with the Carthaginians and was unable to take charge.

Learning about of Sempronius’ inexperience and rash personality, Hannibal devised a plan where he would have his cavalry draw the Roman Army into open battle at the time and place of his choosing. One morning, the African cavalry began harassing the Roman camp and Sempronius pulled his entire force of roughly 42,000 and began advancing on the enemy. Hannibal quickly organized his own army and battle commenced. Yet, unbeknownst to the Romans, roughly 2,000 Carthaginian soldiers were lying in wait in some tall grass to the side of the battlefield.

When the Roman lines passed them in the thick of battle, these troops emerged from hiding and attacked their rear. Being almost completely surrounded, the Roman forces began to disintegrate. In the aftermath, at least 15,000 Romans died and another 15,000 were captured. Roughly 10,000 did manage to fight their way through the enemy lines and escape to safety. The Carthaginians lost roughly 5,000 men, most of them Gauls.

7. The Battle of Lake Trasimene (217 BC)

As the second in a string of major Carthaginian victories against the Romans, the Battle of Lake Trasimene is considered to be one of the largest ambushes in history. After the battle of the Trebia River one year prior, Hannibal marched his forces south, right in the heart of the Italian Peninsula. In hot pursuit was General Gaius Flaminius, who believed the enemy would march on to Rome. Yet, the Carthaginians began moving east towards the present-day city of Perugia. Knowing the Romans were on their tail, Hannibal devised a cunning plan for the shore of Lake Trasimene. Cramped between the water’s edge and a hill, this valley acted as a perfect place for an ambush.

The Carthaginian General timed his crossing of this narrow path just right, so as to allow the Romans see them on the other side of the valley just as night fell. The following morning, Gaius Flaminius marched his forces through the mist-covered valley so as to engage the Carthaginians on the other side. But as the last of the soldiers entered the crossing, thousands of Gauls began charging down the hill, plus the Carthaginian cavalry attacking them from the rear. Pinned in the middle, many Romans drowned in the lake, trying to escape the onslaught. Of the initial Roman force of roughly 30,000, only about 10,000 managed to escape in the heavy mist. General Gaius Flaminius also died in the battle and his body was never recovered. The Carthaginians lost only about 2,500 men.

6. The Battle of Cannae (216 BC)

As one of the most significant battles in history, the engagement at Cannae is seen by military tacticians today as a classic example of a double envelopment victory. Taking place in southern Italy in 216 BC, the battle was fought between the numerically superior Romans, with over 80,000 men, and the Carthaginians, with about 50,000. Reaching the battle site first, the Carthaginians took up a favorable position that would diminish the numerical advantage of the Romans.

Feeling encouraged by one of the largest armies ever assembled by that point, the Romans believed that they would make short work of the Carthaginians and rid themselves of their threat for good. Their strategy was straightforward – to put the bulk of the forces in the center and overwhelm the enemy with brute strength of numbers. Hannibal, however, went the other way and maximized his advantage by using the terrain and by putting the bulk of his own forces to the sides of the formation.

Once the battle commenced, the Romans were making a steady advance into the Carthaginian center, pushing it back with relative ease. But what they didn’t realize, however, was the fact that this was Hannibal’s plan all along – to have his own center slowly pull back and trick the Romans into allowing themselves to become surrounded. Once this happened, their numerical advantage turned on them as they were no longer able to move and fight effectively. In the aftermath, only about 14,000 Romans managed to escape, another 10,000 were captured, while the rest died. Among the dead were also 28 of Rome’s 40-total tribunes, 80 Senators, and roughly 20 percent of the Republic’s entire male fighting population. The Carthaginians lost only about 6,000 men.

5. The Battle of Noreia (112 BC)

For reasons not mentioned in the history books, two tribes of Proto-Germanic people, the Cimbri and the Teutons, decided to leave their homeland of what is now Denmark and emigrate en masse toward the south. In 113 BC, they encountered the Taurisci in present-day Slovenia. The Taurisci were allies of Rome, and asked them for help in dealing with the overwhelming threat. Consul Gnaeus Papirius Carbo was sent to deal with the situation. He arrived ahead of some 30,000 troops and made a show of force in front of the Cimbri and Teutons. Hearing rumors about Rome’s military might, the two tribes accepted Carbo’s proposal to leave. He even offered several guides to escort them to the border.

Yet, as a politically ambitious man, Gnaeus Carbo was not content with a simple peaceful resolution – he wanted a military victory. He instructed the guides to lead the tribesmen towards the town of Noreia in present-day Austria, where he would lay an ambush. The Cimbri somehow found out about the plot on the way and took the Romans by surprise instead. About 6,000 Legionnaires did manage to escape, thanks in large part to a freak thunderstorm that helped them vanish into the forest. Carbo was among them. He returned to Rome in shame, where he was impeached as consul and committed suicide soon after. The outcome of the battle left the Roman lands exposed to the victorious tribesmen but they, instead, decided to head west into Gaul.

4. Battle of Arausio (105 BC)

For several years after the battle of Noreia, the Cimbri and the Teutons disappear from written record. It would take another seven years before they encountered the Romans again, this time on the other side of the Alps, in what is now southern France. A sizable Roman garrison was already in the region after subduing a local rebellion but it was no match against the roughly 200,000 tribesmen. A second army was sent from Rome, led by consul Gnaeus Mallius Maximus, bolstering their forces to a total of around 80,000 fighting men.

Yet, things were not looking good for the Romans from the start. Though a consul and the rightful man to take the command of the combined armies, Maximus lacked any real military experience and was not of noble birth. The man in charge of the other Roman army, proconsul Quintus Servilius Caepio, was not in favor of Maximus and refused to join the two forces under his command.

When the Cimbri arrived at the scene, they were unaware of this division among the two Roman leaders and decided to open talks with Maximus. Probably thinking that Maximus would take all the glory if he managed a successful negotiation, Caepio decided to take his own forces and attack the Cimbri while the talks were still taking place. The battle was quick and decisive – Caepio lost. Feeling betrayed and emboldened by the victory, the tribesmen proceeded to attack Maximus’ camp as well – with a similar result. All 80,000 Roman soldiers were killed, plus an extra 40,000 that included noncombatants and auxiliary troops. Luckily for Rome, however, the tribesmen didn’t march on to the city but opted, for some reason, to go into the Iberian Peninsula instead. By most accounts, this was the most terrible military defeat in the history of the Roman Republic.

3. The Battle of Carrhae (53 BC)

As the richest man in Rome at the time and notorious for his insatiable greed, Marcus Licinius Crassus decided to initiate a war with the Parthian Empire in what are now parts of eastern Turkey, Iran, and Iraq. Even though the Senate was mostly opposed to a conflict with the Parthians, calling it “a war with no justification,” they had little say in the matter given the fact that Crassus was part of the so-called First Triumvirate, a term used to describe the political alliance between Rome’s three most influential figures, Crassus, Pompey Magnus, and Julius Caesar. After some easily-won victories against the kingdoms of Pontus and Armenia, Crassus believed he would make short work of the Parthians as well.

Sailing to Syria in 55 BC, Crassus gathered roughly 50,000 men for the invasion. Disregarding the advice to go through Armenia into Parthia, the Roman general decided instead to go straight through the desert and capture any cities he encountered. As they neared the settlement of Carrhae, however, a Parthian force led by general Surenas was approaching. Numbering only 10,000 in total, the army was comprised of 9,000 horse archers and 1,000 cataphracts – heavily-armored cavalry.

Not being able to outmaneuver them, Crassus ordered a hollow square formation so as to prevent outflanking. The 9,000 archers then began showering them with arrows. Even though the sturdy Roman shields could withstand against such an attack, some arrows did make it through, either nailing their arms to the shields or nailing their feet to the ground. The hope was that the Parthians would run out of arrows sooner or later but that never happened. General Surenas was using a camel caravan to resupply them. The ordeal lasted for two days until Surenas offered peace talks. These went badly, however, and Crassus was killed. In the aftermath, over 20,000 Romans died and another 10,000 were captured, while the Parthians suffered minimal casualties.

2. The Battle of the Teutoburg Forest (9 AD)

Also known as the “Varian Disaster” and oftentimes regarded as Rome’s greatest defeat, the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest, in what is now central Germany, was an epic engagement between three Roman Legions and six auxiliary cohorts led by Publius Quinctilius Varus, and an alliance of Germanic tribes led by Arminius, a Germanic chief and former officer and part of Varus’ auxiliary forces. Arminius was made a Roman citizen and received the famous Roman military education – something that played an important role in the outcome of the battle.

Though not yet fully committed to conquering Germania, east of the Rhine River, the Romans were nevertheless looking to expand their influence over the region. In fact, many Germanic tribes were already allies of Rome. Knowing full well what their end goal was, Arminius devised a plan to drive the Romans out of area for good. He told Varus that there was a minor uprising to the north and they needed the Romans’ help to crush it. The legions began marching in that direction, reaching the Teutoburg Forest sometime in September of 9 AD.

When the legions began entering the forest, their lines were stretched for more than 10 miles and not in a battle formation. Along a narrow, muddy path, sandwiched between two steep and heavily wooded hills, the many Germanic tribes descended on the unaware Romans with overwhelming force. Half of the roughly 36,000 men died in this attack. They managed to regroup, however, and build a fort. They marched south the following day, only to come across a large earth and timber rampart that was lined by Germanic tribesmen. They tried storming the defenses but were driven off. The Roman cavalry ran away but was hunted down over the following days. Only about 1,000 Romans managed to reach safety, while the rest were either killed or enslaved. Varus committed suicide.

Despite several more successful raids and minor battles, the Romans would never again try to conquer the lands east of the Rhine River. This battle is considered by many to be a turning point in world history.

1. The Battle of Edessa (260 AD)

The third century AD was a particularly tumultuous one for the Roman Empire. For nearly 50 years, the empire was at great threat of implosion, going through a period of so-called Military Anarchy with 26 claims to the throne, mostly from Roman military generals. After defeating the usurper Aemilianus, Valerian – who was a Roman general himself – assumed the throne in 253 and quickly travelled to the eastern provinces to restore order in that region. In early spring of 260 AD, a sizable Sassanid army led by the King of Kings, Shapur I the Great, attacked western Mesopotamia, which was then part of the Roman Empire.

To counter the threat, Emperor Valerian gathered some 70,000 troops from many corners of the Empire, as well as some Germanic allies, and marched into the region, making great headway. But by the time they reached Edessa, a fortified city in what is now southeastern Turkey, the Roman army was hit by a plague. Valerian decided to hole up in Edessa, but the Persians laid siege to it almost immediately. With so many of his men unable to fight, Valerian decided to go and negotiate with Shapur, only to be taken prisoner and escorted back to Persia. This was the first time a Roman Emperor was captured. What happened in the aftermath is unknown but scholars believe the Roman army surrendered without a fight.

Interpretations on what happened to the prisoners differ among historians, but it’s generally accepted that the Romans were taken to the city of Dezful, in present-day southern Iran. Here, the prisoners were put to work on the Dezful Bridge, the oldest usable bridge currently in existence and an iconic landmark in the region. Some scholars say that Valerian and his men were treated kindly by the Sassanids, while others believe the opposite. Nevertheless, Valerian died in captivity sometime over the following years while in his 60s. As of 2010, cars and other motor vehicles are no longer allowed on the Roman-built Bridge, due to its historical significance.