Last year, we dug up some of the forgotten skeletons buried deep in America’s closet by examining 10 ghastly moments that won’t often make it in the history books. But the United States is hardly the only place with a few dark secrets so, today, we take that spotlight and shine it on Great Britain.

10. The Peterloo Massacre

On August 16, 1819, a large crowd of 60,000 working class people gathered in St. Peter’s Field (now St. Peter’s Square) in Manchester to advocate for parliamentary representation at a time when only the rich, land-owning elite were allowed to vote. According to contemporary reports, the protesters were, by and large, orderly and disciplined, dressed in their best outfits, carrying around banners that said things like “Universal Suffrage” and “Equal Representation.” In exchange, the magistrates sent in the cavalry who immediately started cutting people down with sabers and stomping them to death.

An estimated 14 to 18 people were killed during the massacre while another 600 to 650 were injured. The government sided with the local magistrates and their priority then became to crack down on those trying to spread word of the Peterloo Massacre, as it became known, under the charge of sedition. The organizers were arrested, as were journalists, particularly those from the radical publication the Manchester Observer.

Even in modern times, the government has had issues properly addressing what really happened at St. Peter’s Field. Up until recently, the only reminder of what occurred on that spot was a blue plaque that simply said that the military dispersed a crowd of 60,000, carefully omitting the word “massacre.” It wasn’t until 2007 that a new, truthful plaque took its place.

9. The Revolt of 1196

In the 12th century, rebellions were usually the product of nobles and royals fighting against each other. Peasants rarely caused uprisings because they lacked the numbers, the resources, and the weapons to avoid being crushed immediately. One notable exception occurred in 1196 when one man named William FitzOsbert, also known as William Longbeard, gathered tens of thousands of followers from the peasantry of London by advocating for better conditions for the poor.

Another point that makes this rebellion unique is that we have a detailed account from an actual contemporary of FitzOsbert – the English historian William of Newburgh who presented it in his Historia rerum Anglicarum. He described FitzOsbert as being a man “of ready wit, moderately skilled in literature, and eloquent beyond measure.” He also called him a “most inhuman man” and accused FitzOsbert of merely inflaming the people with talk of liberty and rights in order to target prosperous nobles he deemed inferior to himself.

According to the historian, at the height of his popularity, Longbeard had 52,000 followers who had began stocking iron tools to use as weapons in an eventual rebellion. He walked everywhere surrounded by an entourage, knowing that he would be a target for assassination.

Eventually, one confrontation turned violent and, after two men were killed, FitzOsbert and some of his followers took refuge in the Church of St Mary-le-Bow. Armed guards decided to burn it down, however, and captured Longbeard when he was forced to flee the flaming edifice. FitzOsbert was drawn and quartered along with his closest conspirators.

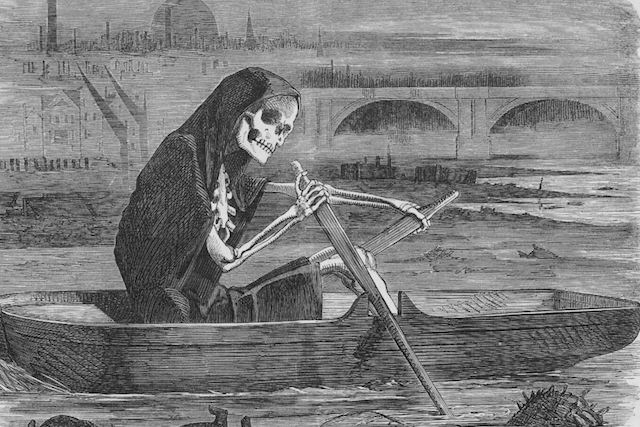

8. The Great Stink

Not all dark moments have to be bloody. Some of them can be downright repulsive, like the summer of 1858 which went down in London history as “the Great Stink.”

For hundreds of years, the River Thames had been used as a dumping ground for all kinds of waste. The problem increased in magnitude during the 19th century as the Industrial Revolution kicked into full swing – London’s population ballooned to millions of people, not to mention that the Thames was now also full of industrial waste. In the words of scientist Michael Faraday, the river had turned into “an opaque pale brown fluid.”

Things came to a head in July 1858, when London was hit by a giant heatwave, fermenting all the disgusting sewage and releasing its foul odor upon the masses. The stench was so bad that some people were completely knocked down by it while others were seen running for the hills with their handkerchiefs covering their faces. What made matters truly horrific was that many had no other source of water than the Thames and the city had seen many outbreaks of cholera and diphtheria.

Bizarrely, the fact that the stink was so pervasive and so repulsive might have been a good thing because it finally forced the government to act. At first, they seemed inclined to simply find a solution for themselves and leave the problem for another day. Initially, they tried to douse the curtains of Parliament with chloride and lime to keep out the smell, but that didn’t work. Then they talked about moving to another building, further away from the Thames, but that wasn’t an option, either. Finally, they approved the building of a new, complex sewage system, a project spearheaded by civil engineer Joseph Bazalgette.

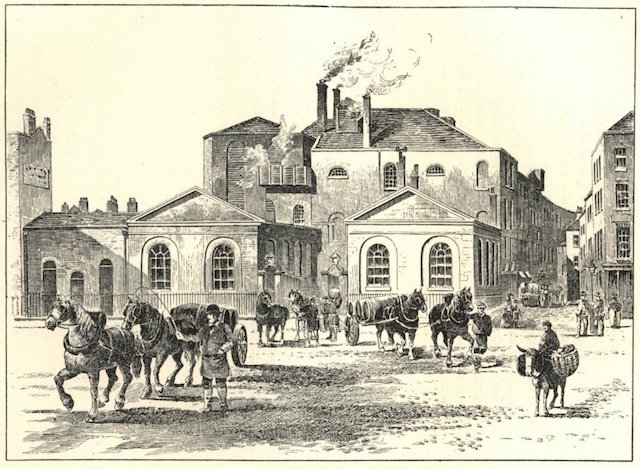

7. The London Beer Flood

On October 17, 1814, in a house on New Street, London, a mother named Anne Saville was holding a wake, mourning the loss of her toddler son. In another house, four-year-old Hannah Bamfield was having a tea party with her mother. Nearby, a 14-year-old working girl named Eleanor Cooper was scouring pots outside a pub called the Tavistock Arms. All three of them and five others would lose their lives in an instant when their neighborhood was inundated with a 15-foot high tidal wave of beer.

The source of this tragedy was the Horse Shoe Brewery. It had a giant vat 22 feet tall which contained anywhere between 3,500 and 7,500 barrels of porter, depending on the source. If you’re wondering why the brewery would make vats so big, it’s because the vats were somewhat of an attraction back then and London brewers would brag about having the biggest ones.

On that fateful day, a brewery employee noticed that one of the giant, 700-pound iron hoops fitted around the vat had slipped off. Now this was a problem that happened several times a year so there was no immediate concern. They just made a note to fix it later but, after an hour, the vessel burst suddenly. The force of the liquid also caused a nearby vat to spill its contents so now there were a few hundred thousand gallons of beer running amok. The porter completely knocked down the back wall of the brewery and flooded the nearby streets, causing eight fatalities and dozens of injuries.

An inquest ruled the event an “act of God.” The brewery didn’t have to pay the victims and their families anything, but it did receive a waiver from Parliament to excise taxes on the beer it lost.

6. The Murderous Midwife

With the emergence of killers such as Jack the Ripper, Victorian England became familiar with the depths of deranged depravity that people could reach. Even so, those dark corners of humanity were strictly the domain of men. In their puritanical views, women would never display such cruelty. Those views changed when they met Mary Pearcey.

On December 23, 1890, Mary Pearcey was executed at Newgate Prison for the gruesome murders of Phoebe Hogg and her baby daughter. Pearcey was having an affair with Phoebe’s husband, Frank Hogg, and probably wanted to get them out of the way.

Two months prior to the execution, the body of Phoebe Hogg was discovered on top of a trash heap in Hampstead. She had several superficial wounds, but her throat had been slashed so deeply that it was almost severed from the body. In another area, the baby had been found in her own carriage, smothered to death.

Frank Hogg was the obvious initial suspect, but the evidence soon piled up against Mary Pearcey. She had met with Phoebe the day of the murders. Neighbors heard loud noises coming from her house. Inside, there were obvious signs of a struggle. Mary’s clothes, furniture, fire poker, and carving knife all had blood stains on them. The case was open and shut and Pearcey was sentenced to death. The crimes of Mary Pearcey were so shocking that she became suspected of being Jack the Ripper.

5. The Popish Plot

During the late 1670s, the Kingdoms of England and Scotland were gripped by an anti-Catholic hysteria. It reached a fever pitch with the exposure of the Popish Plot, a conspiracy to assassinate King Charles II so that his brother James, who was a Roman Catholic, would inherit the throne. At least 22 men alleged to be part of this conspiracy were executed, not to mention all the random violence perpetrated against Catholics around the kingdoms. There was just one issue with the Popish Plot – it had all been invented by one man.

That man was a priest named Titus Oates. He originally wanted to join the Catholic Church and enrolled in the Jesuit Royal English College in Valladolid, Spain. However, his unlikeable demeanor, his theological incompetence, and penchant for blasphemy soon got him kicked out. Therefore, in 1678, he returned to England with tales of a Catholic conspiracy, claiming he only joined them to unearth their secrets.

Oates got people believing that the Jesuits were planning to murder King Charles II and replace him with his brother with the support of France. This led to the Exclusion Crisis which saw multiple attempted bills to exclude James as heir presumptive.

The so-called Popish Plot generated a lot of hysteria as people believed it was the Gunpowder Plot all over again. Catholics were driven out of London. People burned effigies of the pope. Catholic officials were arrested; some of them were executed; others died in prison.

It took a few years until Parliament realized that this “damnable and hellish plot” was a fabrication of Oates, a man who was later tried for perjury and described as “a shame to mankind.”

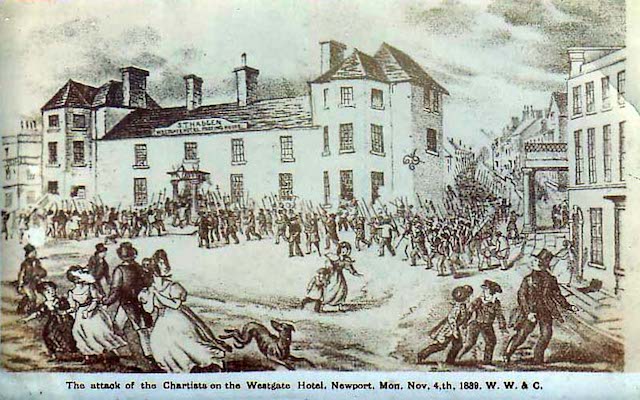

4. The Newport Rising

Chartism was a labor movement that existed during the mid 19th century. It had six points of reform it aimed to institute but, by and large, the overall goal was to make it easier for working class men to get involved with Parliament.

As with most labor movements of the 19th century, this one had violent clashes between protesters and “the powers that be” which had little interest in making themselves more accountable to the working classes.

One such confrontation took place on November 4, 1839, in Newport, Wales. Led by prominent Chartist member John Frost, up to 10,000 protesters marched on the town, many of them armed with homemade weapons, with the intent of freeing other Chartist sympathizers they believed were unjustly imprisoned at the Westgate Hotel.

Soldiers were waiting for them and, while they were outnumbered, they had superior firepower. The skirmish lasted for about half an hour. Around 22 Chartists were killed, dozens more were injured and hundreds were arrested later. The leaders of the uprising were all sentenced to be hanged, drawn and quartered, although their sentences were commuted to penal transportation for life.

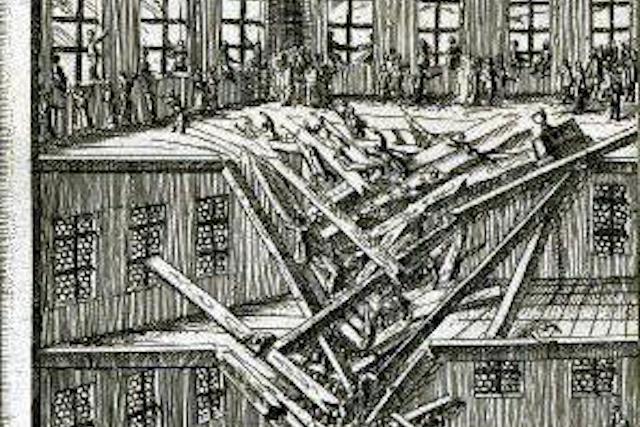

3. The Fatal Vespers

On October 26, 1623, around 300 men, women, and children gathered at Hunsdon House in Blackfriars, London. It was the home of the French ambassador and everyone was there to take part in vespers, an evening prayer service for Catholics. During the sermon, the upper floor collapsed under the weight of all the people, killing a third of those in attendance.

A contemporary pamphleteer described the scene: “What a chaos!…Here some buried, some dismembered, some only parts of men; here some wounded and weltering in their own and others’ blood; others putting forth their fainting hands and crying out for help.”

As it turned out, the main beams of the house were ten inches in thickness, but they had mortise holes where the girders were inserted and there they were only three inches thick. This was simply not enough to hold the weight.

Because this was only 18 years after the Gunpowder Plot, resentment against Catholics was still high. Some declared it as divine vengeance, while contemporary accounts claimed that witnesses who had “grown savage and barbarous” looked on with glee and malice, taunting and mocking the dead and dying instead of offering assistance.

2. The Colney Hatch Fire

Centuries ago, there was a little hamlet outside London called Colney Hatch. It attained notoriety around the mid 19th century when it became home to one of the country’s biggest lunatic asylums for the poor. Given how little regard such people were afforded back then, it shouldn’t surprise you to find out that the conditions they lived in were miserable and that the building itself was poorly-maintained and, basically, just one big fire hazard.

On January 27, 1903, the inevitable happened. The asylum which housed hundreds of patients caught fire. Over 200 firemen manning 35 engines rushed to the scene, but the blaze spread to multiple wards by the time they arrived. Some were hit harder than others and contained only charred remains that could no longer be identified.

Fifty-two people perished in the fire and another 330 were crippled. Since then, the asylum had been rebuilt and, eventually, renamed to Friern Hospital. Nowadays, it has been turned into luxury apartments that promise a “link with the glory of Victorian England,” yet there is no mention of the tragedy that once occurred there.

1. St Scholastica Day Riot

“Town and gown” is a term used to refer to the two distinct populations of a college town: the university community and the regular townspeople. Conflicts often arose between these two groups, particularly in medieval times when the townsfolk had deep resentment for the academics for the various privileges they enjoyed. Oftentimes, these conflicts turned violent, but none more so than the St Scholastica Day Riot that took place at Oxford.

It all started on February 10, 1355, when a group of students went into town for a drink. They stopped at the Swindlestock Tavern, but an argument soon erupted between two of the students and the pub landlord over the quality of the wine. More people joined the quarrel on both sides and, before long, a brawl broke out. Soon afterwards, someone rang the bells of the nearby church to summon more people while, on the other side, a student also rang the university church bell for aid. The fight now evolved into a full-blown riot.

Up to 2,000 people arrived from nearby villages, many of them armed. The students and faculty were outmatched in every way. For three days, the rioters marched to all the inns and halls where the students lived and pillaged them all, often killing whomever they encountered. When the slaughter ended, an estimated 30 locals and 63 students lay dead.