By the late second century BC, several empires and dynasties jostled for control of the Mediterranean. The crowded region featured the well-established Romans, Greeks, and Egyptians, but an emerging new power would soon reign supreme over its rivals. Based on the coast of North Africa in present-day Tunisia, Carthage grew to become the most dynamic city in the world — and led by a brash general and those notorious war elephants.

His name, of course, was Hannibal Barca, and in addition to making a thundering entrance on the battlefield, the venerated general orchestrated legendary victories against the mighty Romans. Carthage rule eventually claimed a significant portion of coastal territories including the islands of Sardinia, Corsica, and Sicily. But like all empires, nothing lasts forever — although cockroaches and Keith Richards may have something to say about that.

From the Ashes

The port of Carthage initially developed as an extension of the Phoenician city of Tyre (present-day Lebanon). Founded by Queen Dido in the 9th century BC, the Phoenicians named it Qart-hadasht, which simply means “new town.” The Carthaginians gained their independence in 650 BC and blossomed into a prosperous, seafaring nation built on maritime commerce.

The former colony would build outposts of its own as they created a vast network throughout the surrounding areas along with key ports in Arabia, Africa, and India. Looking to expand their burgeoning empire and wealth, Carthage later transitioned into becoming a dominant military force on both land and sea.

One-Stop Shopping

As a precursor to a certain behemoth online warehouse named for a river (okay, it’s Amazon), Carthage operated a prosperous commercial trading center that involved buying and selling products from Britannia to Persia. The extensive catalog included items such as timber, metals, textiles, spices, and precious stones. The trading of tin, an essential component in making bronze, became an especially lucrative business — thanks in part to a monopoly of mines in mineral-rich Iberia.

The enterprising North Africans also manufactured a wide selection of made-in-Carthage goods and homegrown crops; sophisticated viticulture provided widely exported wines that were decanted in distinctive cigar-shaped amphorae; and their location in the Mediterranean provided a logistical advantage over its competitors, serving as a centralized distribution hub from which to launch its trade routes.

War and Peace

Carthage brokered a peace treaty with Rome In 509 BC, hoping to protect and regulate its imports and exports. But the Merchant of the Med inevitably got into the business of war, swapping widgets for weapons to confront pirates and rival nations, and all others wanting a piece of their booty.

They soon amassed an enormous mercenary army from Celtic tribes and African allies to complement its powerful navy. Between 480 BC and 265 BC, the Carthaginians fought a series of wars over the control of Sicily primarily against Greek forces.

The Sicilian Wars eventually led to a major showdown with Rome, producing three separate conflicts known as the Punic Wars (“Punic” comes from the Latin word “Punicus” and what the Romans called people from Carthage). For well over a century, the two warring sides went at each like Ali vs. Frazier with an occasional, short-lived truce thrown in for good measure.

Family Business

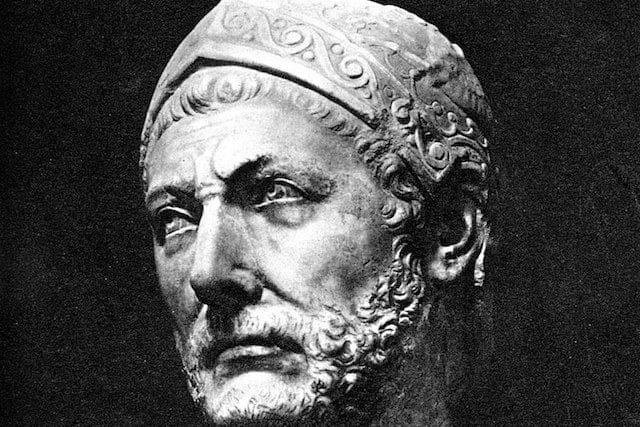

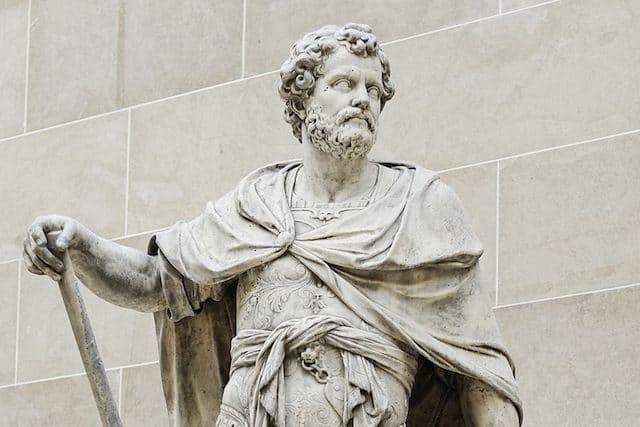

The Barca surname is derived from the Punic word barqa meaning “lightening.” It’s a fitting description of the family pledged to fight Rome and whose actions would play an integral role in determining the course of Western Civilization.

Led by its patriarch, Hamilcar, the Carthaginian general produced three sons: Hannibal, Hasdrubal, and Mago, all of whom became successful military leaders. Additionally, one of his daughters married Hasdrubal-the-Fair, a powerful governor of Iberia and successful general in his own right. It’s also worth noting that Hamilcar’s grandson, Hanno, had a well-earned reputation as a skilled cavalry officer and played a crucial role in Rome’s greatest defeat (more on that later).

Hannibal, along with Alexander the Great and Julius Caesar, easily ranks as one of the greatest generals in ancient times. According to legend, the fate of the Carthaginian was sealed when his father took him to the temple of Baal, making the nine-year-old boy swear to be an eternal enemy of Rome.

Hannibal would accompany his father onto the battlefield, receiving an invaluable military education when most boys are merely playing with toy soldiers. After a string of remarkable triumphs, he eventually tasted defeat at the Battle of Zama in 202 BC, and later committed suicide rather than capitulate to the Romans.

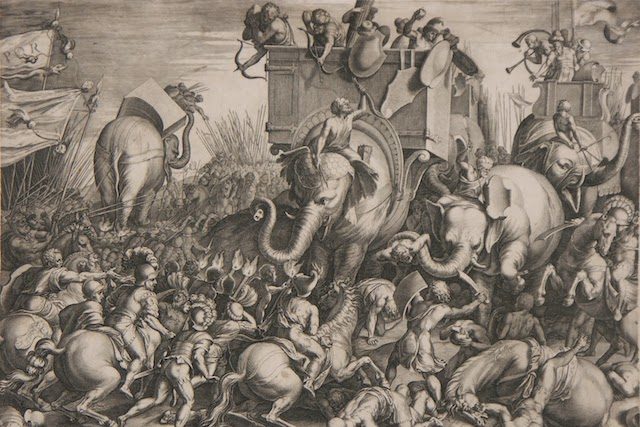

Jumbo Sized

Wealthy. Daring. Powerful. For many ancient cultures, living large reached epic proportions — and no list about Carthage is complete without giving proper respect to one of the most decadent weapons in history.

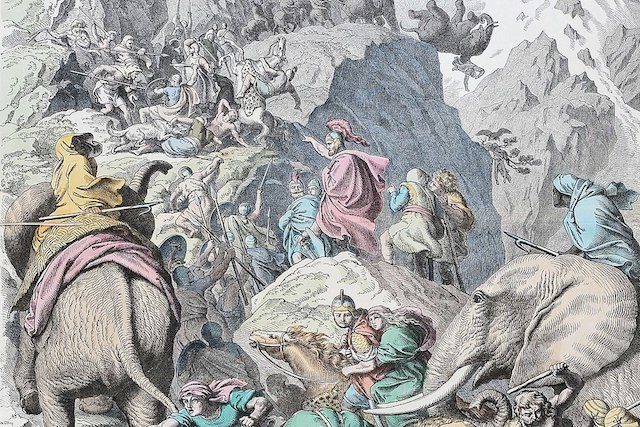

Imagine being a Roman legionnaire and stepping onto the battlefield for the first time. Sporting a wooden javelin and perhaps some shiny, new armor replete with sexy-looking molded abs and pecs, one might feel pretty invincible while brimming with youthful vigor. That is until a raging 5,000 pound beast with long, sharp tusks came rumbling along, causing the soldier to run like a thief with a handbag through the cobblestones of Rome.

The now extinct North African forest elephant once thrived all along the coastline from Morocco to Egypt. Although not as big as varieties found in the central and southern regions of Africa or India, the mammoth creatures were made even more lethal by adding sharp spears to the tusks. Furthermore, the well-trained elephants were given wine (probably red) before going into battle to make them more aggressive and amplify their trumpeting.

Art World

Similar to the melting pot of its Phoenician mother country, Carthage attracted a wide range of artists from across the Mediterranean and beyond. The cosmopolitan atmosphere produced exquisite artwork in numerous mediums, infusing established styles as well as creative forms that were uniquely Carthaginian.

The constant influx of imported and exported goods helped not only introduce various artistic influences but also provided an ample surplus of materials. Coveted purple dyes, ivory, metals, and stone transformed into pieces ranging from fine jewelry to elaborate burial tombs.

The goddess Tanit served as a popular motif in figurines and busts throughout the empire. She is typically associated with the moon and the sea, and like Astarte, was worshipped as a Mother Goddess and city-state protectress.

As the poster boy of an empire and the Mo Salah of his day, Hannibal saw his likeness plastered on everything from sculpture to coins — a reflection of the kind of adulation that comes from whipping Rome while riding on the back of an elephant. Although to date, no statue has ever been found of the ancient North African wearing a Golden Boot.

OMG

Citizens of Carthage practiced a blend of polytheism, borrowing divinities from neighboring civilizations in Greece, Egypt, and the Levant. Worship centered around the primary gods Baal-hamon and his wife, the goddess Tanit, and spirited rituals that included food, libations, and dancing. They also sacrificed children.

A 2014 study by faculty at Oxford University concluded that “…all the evidence – archaeological, epigraphic and literary – it is overwhelming and, we believe, conclusive: they did kill their children.” Historians have long debated whether the claims of infanticide in Carthage were the result of Greek and Roman propaganda or an ugly truth that systemically occurred for centuries.

An excavation of Carthaginian cemeteries known as tophets revealed thousands of graves containing cremated bones carefully packed into ceremonial urns. Although many archaeologists and historians determined the findings to be proof of infanticide, others insisted the funerals illustrated compassion for the deceased.

The Roman historian Diodorus, however, wrote this graphic account: “There was in their city a bronze image of Cronus, extending its hands, palms up and sloping towards the ground, so that each of the children when placed thereon rolled down and fell into a sort of gaping pit filled with fire.”

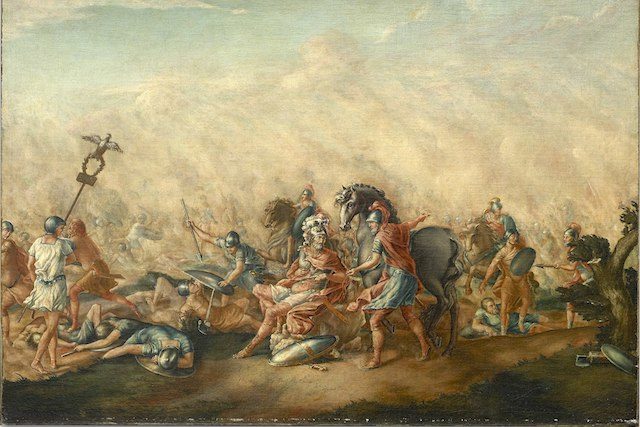

Can We Kill Some Romans?

Among the bloodiest battles in history, the Battle of Cannae in 216 BC stands out as both tactically brilliant and equally horrific. Roughly 50,000 Roman soldiers were killed or captured by a much smaller force (possibly as few as 10,000), and has been characterized by historians as the perfect ‘battle of annihilation’.

After suffered two crushing defeats at Trebia and Lake Trasimene during the Second Punic War, the Roman army attempted to regroup near the village of Cannae in southeast Italy. Hannibal, however, had other plans. Despite losing most of his elephants during the arduous trek across the Alps, he set his sights on finishing off his nemesis once and for all.

The Roman battle plan called for a straightforward frontal assault, concentrating heavy infantry in the center to drive through the Carthaginian army. Anticipating this line of attack, Hannibal deployed his brother Hasdrubal and his nephew Hanno on the Roman flanks while allowing his middle position to collapse. The double-envelopment maneuver allowed the swift-moving cavalry, including seasoned Numidian and Celtic horsemen to corral and trap the enemy, resulting in total slaughter.

Crash and Burn

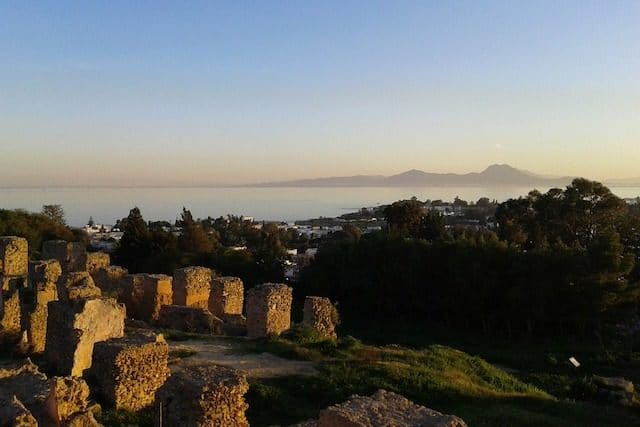

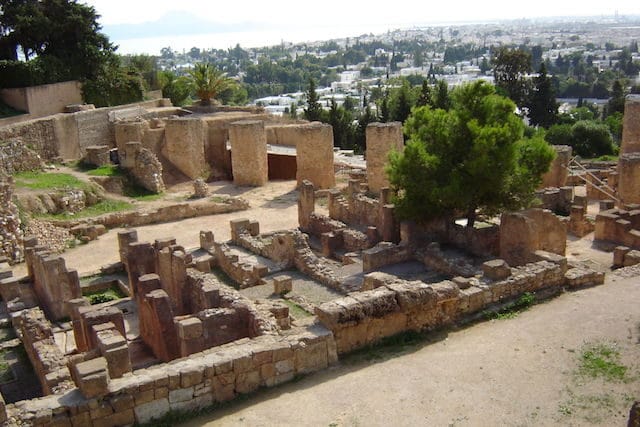

The Third Punic War, unlike the previous two engagements, saw the Romans take the attack directly to Carthage. Fought between 149 BC and 146 BC, the invading forces decisively conquered the capital city, bringing an end to the Carthage Empire by burning everything to the ground, including most primary sources of their highly complex culture.

Julius Caesar later had the city rebuilt as a vital seaport of the Roman Empire. Over the next several centuries, Carthage experienced a steady stream of occupying forces, including the Vandals, Byzantines, Muslims, and Crusaders.

Today, the ruins of the former great empire can be found on the outskirts of the Tunisian capital of Tunis.